Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by the English kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against the Kingdom of France. The modern Royal Navy traces its origins to the early 16th century; the oldest of the UK's armed services, it is known as the Senior Service.

|

| Her Majesty's Naval Service of the British Armed Forces |

|---|

| Components |

|

|

| History and future |

|

|

| Ships |

| Personnel |

| Auxiliary services |

From the middle decades of the 17th century, and through the 18th century, the Royal Navy vied with the Dutch Navy and later with the French Navy for maritime supremacy. From the mid 18th century, it was the world's most powerful navy until the Second World War. The Royal Navy played a key part in establishing the British Empire as the unmatched world power during the 19th and first part of the 20th centuries. Due to this historical prominence, it is common, even among non-Britons, to refer to it as "the Royal Navy" without qualification.

Following World War I, the Royal Navy was significantly reduced in size,[4] although at the onset of World War II it was still the world's largest. During the Cold War, the Royal Navy transformed into a primarily anti-submarine force, hunting for Soviet submarines and mostly active in the GIUK gap. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, its focus has returned to expeditionary operations around the world and it remains one of the world's foremost blue-water navies.[5][6][7] However, 21st-century reductions in naval spending have led to a personnel shortage and a reduction in the number of warships.[8][9]

The Royal Navy maintains a fleet of technologically sophisticated ships, submarines, and aircraft, including two aircraft carriers, two amphibious transport docks, four ballistic missile submarines (which maintain the UK's nuclear deterrent), seven nuclear fleet submarines, six guided missile destroyers, 13 frigates, 13 mine-countermeasure vessels and 23 patrol vessels. As of April 2020, there are 77 commissioned ships (including submarines) in the Royal Navy, plus 13 ships of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA); there are also five Merchant Navy ships available to the RFA under a private finance initiative. The RFA replenishes Royal Navy warships at sea, and augments the Royal Navy's amphibious warfare capabilities through its three Bay-class landing ship vessels. It also works as a force multiplier for the Royal Navy, often doing patrols that frigates used to do. The total displacement of the Royal Navy is approximately 448,600 tonnes (824,600 tonnes including the Royal Fleet Auxiliary).

The Royal Navy is part of Her Majesty's Naval Service, which also includes the Royal Marines. The professional head of the Naval Service is the First Sea Lord who is an admiral and member of the Defence Council of the United Kingdom. The Defence Council delegates management of the Naval Service to the Admiralty Board, chaired by the Secretary of State for Defence. The Royal Navy operates from three bases in the United Kingdom where commissioned ships and submarines are based: Portsmouth, Clyde and Devonport, the last being the largest operational naval base in Western Europe, as well as two naval air stations, RNAS Yeovilton and RNAS Culdrose where maritime aircraft are based.

Role

As the seaborne branch of HM Armed Forces, the RN has various roles. As it stands today, the RN has stated its 6 major roles as detailed below in umbrella terms.[10]

- Preventing Conflict – On a global and regional level

- Providing Security At Sea – To ensure the stability of international trade at sea

- International Partnerships – To help cement the relationship with the United Kingdom's allies (such as NATO)

- Maintaining a Readiness To Fight – To protect the United Kingdom's interests across the globe

- Protecting the Economy – To safeguard vital trade routes to guarantee the United Kingdom's and its allies' economic prosperity at sea

- Providing Humanitarian Aid – To deliver a fast and effective response to global catastrophes

History

Development of navies in England and Scotland

Middle Ages

The strength of the fleet of the Kingdom of England was an important element in the kingdom's power in the 10th century.[11] At one point Aethelred II had an especially large fleet built by a national levy of one ship for every 310 hides of land, but it is uncertain whether this was a standard or exceptional model for raising fleets.[12] During the period of Danish rule in the 11th century, the authorities maintained a standing fleet by taxation, and this continued for a time under the restored English regime of Edward the Confessor (reigned 1042–1066), who frequently commanded fleets in person.[13]

Decline of the English Navy under the Normans, 1067–1154

English naval power seemingly declined as a result of the Norman conquest.[14] Following the Battle of Hastings, the Norman navy that brought over William the Conqueror seemingly disappeared from records, possibly due to William receiving all of those ships from feudal obligations or because of some sort of leasing agreement which lasted only for the duration of the enterprise. There is no evidence that William adopted or kept the Anglo-Saxon ship mustering system, known as the scipfryd. Hardly noted after 1066, it appears that the Normans let the scipfryd languish so that by 1086, when the Doomsday Book was completed, it had apparently ceased to exist.[15]

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in 1068, Harold Godwinson's sons Godwine and Edmund conducted a "raiding-ship army" which came from Ireland, raiding across the region and to the townships of Bristol and Somerset. In the following year of 1069, they returned with a bigger fleet which they sailed up the River Taw before being beaten back by a local earl near Devon. However, this made explicitly clear that the newly conquered England under Norman rule, in effect, ceded the Irish Sea to the Irish, the Vikings of Dublin, and other Norwegians.[16] Besides ceding away the Irish Sea, the Normans also ceded the North Sea, a major area where Nordic peoples travelled. In 1069, this lack of naval presence in the North Sea allowed for the invasion and ravaging of England by Jarl Osborn (brother of King Svein Estridsson) and his sons Harald, Cnut, and Bjorn. In addition to the ravaging of the English townships of Dover, Sandwich, Ipswich, and Norwich, the Danes connected with the aetheling (Anglo-Saxon Heir to the crown) Edgar and rebels in Northumbria. William chased Edgar and the rebels to Scotland, but could not defeat the Danes, causing him to resort to the old Anglo-Saxon practice of paying them off.[17]

Though William the Conqueror caused a massive decline in English naval practices, he did occasionally assemble small fleets of ships, but only for limited activities. Most of these limited actions also did not involve direct combat at sea. An example of this was when the rebellious Anglo-Saxon Earl Morcar and his ally Bishop Æthelwine of Durham sought refuge on the Isle of Ely in 1071. According to Florence of Worcester reported, "The king [William the Conqueror] hearing of this, blocked up every outlet on the eastern side by means of boatmen [butescarls], and caused a bridge two miles long to be constructed on the western side." The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also confirms these events. Though William used ships for blockading purposes and for important strategic engagements, his infrequent use of an established navy promoted a damaging practice of infrequent maritime operations, which his successors would practice on a frequent basis.[18]

Medieval fleets, in England as elsewhere, were almost entirely composed of merchant ships enlisted into naval service in time of war. From time to time a few "king's ships" owned by the monarch were built for specifically warlike purposes; but, unlike some European states, England did not maintain a small permanent core of warships in peacetime. England's naval organisation was haphazard and the mobilization of fleets when war broke out was slow.[19]

Barons' Revolt and the evolving English Navy, 1215–1217

When King John’s campaign to recover Normandy from the French was at a breaking point, the northern barons of England began to rise in revolt. Forced by the insurrection, John signed the Magna Carta on 15 June 1215, in hopes of satisfying the barons to buy time for Pope Innocent III to excommunicate the rebellious barons and condemn the Magna Carta. From this, the barons revolted, commencing the First Barons' War with the capture of Rochester Castle. Grasping, however, that they (the barons) were outmatched by royalists and King John, the barons decided to turn to France for assistance. Realizing the baron's intentions, John attempted to assemble a Navy, to prevent the arrival of the French.[20] France, who saw this as a fortunate opportunity, decided to assist the barons, with Phillip II's (King of France) son Dauphin Louis, later known as Louis VIII of France, to invade England. With John unable to swiftly build up his navy, due to the adopting of infrequent maritime operations from William the Conqueror, the French Navy under Louis invaded and landed at Sandwich unopposed in April 1216.[20] With Louis near London, John fled to Winchester, where he would stay until his death on 19 October 1216, having his nine-year-old son Henry III as heir to the throne.[21]

Paradoxically, John's death turned the tide against Louis, the rebellion in England, and the development of the English navy. William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, who became regent to the son of the recently deceased English king, began to regain the loyalties to the royalist cause through a regimen of compromise. Among these were the Cinque Ports, who had substantial amounts of maritime ships. With the English now having a substantial number of vessels, Louis returned to France to gather reinforcements and more maritime vessels. Though he succeeded, English vessels began to blockade and harass French shipping, trade, and blockaded multiple French-controlled English ports.[22]

By mid-1217, English royalists began to gain the advantage over the rebellious Barons and their French allies. Again needing more troops, Louis requested from his wife Blanche of Castile to assemble more troops for him. Up to the task, Blanche assisted in gathering forces for her husband, with a massive French force being assembled by August 1217, at the port of Calais. At the head of the French transports was Eustace the Monk, Louis’ best naval commander, who had helped Louis escape many English blockades, such as the one in Winchelsea in January 1217.[23]

The subsequent encounter between the two fleets came in the Downs off Sandwich, known as the Battle of Sandwich. For the first time in northern waters a decisive naval battle was fought on the open sea. The battle was dominated by the English, with French losing almost all of their ships, including Eustace the Monk who was killed in the action that took place. With the death of Eustace the Monk and the defeat of the French at Sandwich, William Marshal was able to isolate Louis in London, compelling him to renounce his claim to the English throne and force him to return to France.[24]

Scottish and English Navies, 1249–1318

There are mentions in medieval records of fleets commanded by Scottish kings including William the Lion[25] and Alexander II. The latter took personal command of a large naval force which sailed from the Firth of Clyde and anchored off the island of Kerrera in 1249, intended to transport his army in a campaign against the Kingdom of the Isles, but he died before the campaign could begin.[26][27] Viking naval power was disrupted by conflicts between the Scandinavian kingdoms but entered a period of resurgence in the 13th century when Norwegian kings began to build some of the largest ships seen in Northern European waters. These included king Hakon Hakonsson's Kristsúðin, built at Bergen from 1262–63, which was 260 feet (79 m) long, of 37 rooms.[28] In 1263 Hakon responded to Alexander III's designs on the Hebrides by personally leading a major fleet of forty vessels, including the Kristsúðin, to the islands, where they were boosted by local allies to as many as 200 ships.[29] Records indicate that Alexander had several large oared ships built at Ayr, but he avoided a sea battle.[25] Defeat on land at the Battle of Largs and winter storms forced the Norwegian fleet to return home, leaving the Scottish crown as the major power in the region and leading to the ceding of the Western Isles to Alexander in 1266.[30]

English naval power was vital to King Edward I's successful campaigns in Scotland from 1296, using largely merchant ships from England, Ireland and his allies in the Islands to transport and supply his armies.[31] Part of the reason for Robert I's success was his ability to call on naval forces from the Islands. As a result of the expulsion of the Flemings from England in 1303, he gained the support of a major naval power in the North Sea.[31] The development of naval power allowed Robert to successfully defeat English attempts to capture him in the Highlands and Islands and to blockade major English controlled fortresses at Perth and Stirling, the last forcing King Edward II to attempt the relief that resulted at English defeat at Bannockburn in 1314.[31] Scottish naval forces allowed invasions of the Isle of Man in 1313 and 1317 and Ireland in 1315. They were also crucial in the blockade of Berwick, which led to its fall in 1318.[31]

Edward III, Scotland, England and after, 1300–1500

With the Viking era at an end, and conflict with France largely confined to the French lands of the English monarchy, England faced little threat from the sea during the 12th and 13th centuries, but in the 14th century, the outbreak of the Hundred Years War dramatically increased the French menace. Early in the war, French plans for an invasion of England failed when Edward III of England destroyed the French fleet in the Battle of Sluys in 1340.[32] Major fighting was thereafter confined to French soil and England's naval capabilities sufficed to transport armies and supplies safely to their continental destinations. However, while subsequent French invasion schemes came to nothing, England's naval forces could not prevent frequent raids on the south-coast ports by the French and their Genoese and Castilian allies. Such raids halted finally only with the occupation of northern France by Henry V.[33]

Henry VII deserves a large share of credit in fostering sea power. He embarked on a program of building merchant ships larger than heretofore. He also invested in dockyards, and commissioned the oldest surviving dry dock in 1495 at Portsmouth.[34]

After the establishment of Scottish independence, King Robert I turned his attention to building up a Scottish naval capacity. This was largely focused on the west coast, with the Exchequer Rolls of 1326 recording the feudal duties of his vassals in that region to aid him with their vessels and crews. Towards the end of his reign, he supervised the building of at least one royal man-of-war near his palace at Cardross on the River Clyde. In the late 14th century naval warfare with England was conducted largely by hired Scots, Flemish and French merchantmen and privateers.[35] King James I of Scotland (1394–1437, reigned 1406–1437), took a greater interest in naval power. After his return to Scotland in 1424, he established a shipbuilding yard at Leith, a house for marine stores, and a workshop. King's ships were built and equipped there to be used for trade as well as war, one of which accompanied him on his expedition to the Islands in 1429. The office of Lord High Admiral was probably founded in this period.[35] It would soon become a hereditary office, in the control of the Earls of Bothwell in the 15th and 16th centuries and the Earls of Lennox in the 17th century.[36]

King James II (1430–1460, reigned 1437–1460) is known to have purchased a caravel by 1449.[37] Around 1476 the Scottish merchant John Barton received letters of marque that allowed him to gain compensation for the capture of his vessels by the Portuguese by capturing ships under their colours. These letters would be repeated to his three sons John, Andrew and Robert, who would play a major part in the Scottish naval effort into the 16th century.[38] In his struggles with his nobles in 1488 James III (r. 1451–88) received assistance from his two warships the Flower and the King's Carvel also known as the Yellow Carvel, commanded by Andrew Wood of Largo.[35] After the king's death Wood served his son James IV (r. 1488–1513), defeating an English incursion into the Forth by five English ships in 1489 and three more heavily armed English ships off the mouth of the River Tay the next year.[39]

Standing Royal Navy 1500–1707

A standing "Navy Royal",[40] with its own secretariat, dockyards and a permanent core of purpose-built warships, emerged during the reign of Henry VIII.[41] Under Elizabeth I England became involved in a war with Spain, which saw privately owned vessels combining with the Queen's ships in highly profitable raids against Spanish commerce and colonies.[42] In 1588, Philip II of Spain sent the Spanish Armada against England to end English support for Dutch rebels, to stop English corsair activity and to depose the Protestant Elizabeth I and restore Catholicism to England. Preparations, under the command of the Marqués de Santa Cruz, began in 1586 but were seriously delayed by a surprise attack on Cádiz by Sir Francis Drake in 1587. By the time the expedition was ready Santa Cruz had died, and command was given to the Duke of Medina Sedonia. The Armada consisted of 130 ships, including transports and merchantmen, and carried about 30,000 men. It was to go to Flanders and from there convoy, the army of the Duke of Parma, to invade England. It set out from Lisbon in May 1588 but was forced into A Coruña by storms and did not set sail again until July.[43]

The Armada was first sighted by the English off Lizard Point, in Cornwall, on 19 July, and the first engagement took place off Plymouth on 21 July. In four hours the Spanish fired 720 round shot and the English 2,000 rounds, but little real damage was done to either side.[44] In fighting off Portland Bill on 23 July, some 5,000 shots were discharged by the rival fleets. Spanish casualties were about 50 killed and 70 wounded.[45] After another engagement off the Isle of Wight on 24 July, in which the Armada lost another 50 men slain, Medina Sedonia steered for Calais to replenish his empty powder and shot stocks from Parma's ammunition depots. Parma, however, blockaded in Bruges by 60 Dutch ships, was unable to come to the Armada's assistance. After an indecisive engagement with the English off Gravelines, the Armada ran out of ammunition. The Spanish had expended 125,000 cannonballs against the English. Consequently, the Spanish commander decided to retreat to Spain by going north around Scotland and Ireland. The Spanish ships were dispersed by storms; their provisions gave out, and many of those who landed in Ireland were killed by English troops. Only about half the fleet reached home. An English Armada sent to destroy the port at A Coruña in 1589 was itself defeated with 40 ships sunk and 15,000 men lost.[46] In October 1596, another Armada left Lisbon. The invasion fleet numbered 126 ships and carried 9,000 Spaniards and 3,000 Portuguese. The Royal Navy was unprepared, but England was saved by stormy seas that wrecked 72 ships and drowned 3,000 sailors and soldiers.[47] The following year, in October 1597, yet another Armada was sent out, but this also was blown back.[48]

During the early 17th century, England's relative naval power deteriorated, and there were increasing raids by Barbary corsairs on ships and English coastal communities to capture people as slaves, which the Navy had little success in countering.[49] Charles I undertook a major programme of warship building, creating a small force of powerful ships, but his methods of fundraising to finance the fleet contributed to the outbreak of the English Civil War.[50]

In the wake of the civil war and abolition of the monarchy, the Commonwealth of England (as a republic), officially removed or changed most names and symbols (including heraldry) associated with royalty and/or the high church. This affected the Commonwealth Navy. As early as 1646, vessels were renamed, including Liberty (previously Charles), Resolution (ex-Royal Prince) and George (ex-St George); new vessels were often given names associated with institutions or individual officials, including President, Speaker, Fairfax (after Thomas Fairfax), Monck (George Monck) and Richard (Richard Cromwell), or Parliamentary victories in the civil war, such as Worcester, Bristol, Gainsborough, Preston, Langport, Newbury, Martson Moor, Nantwich, Colchester, and Naseby.[51] (The prefix "English ship" has normally been used of naval vessels before the late 17th century; "His Majesty's Ship" was not official usage at the time.) The new regime, isolated and threatened from all sides, dramatically expanded the Commonwealth Navy, which became the most powerful in the world.[52] The Commonwealth's introduction of Navigation Acts, providing that all merchant shipping to and from England or her colonies should be carried out by English ships, led to war with the Dutch Republic.[53] In the early stages of this First Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654), the superiority of the large, heavily armed English ships was offset by superior Dutch tactical organisation and the fighting was inconclusive.[54] English tactical improvements resulted in a series of crushing victories in 1653 at Portland, the Gabbard and Scheveningen, bringing peace on favourable terms.[55] This was the first war fought largely, on the English side, by purpose-built, state-owned warships. It was followed by a war with Spain, which saw the English conquest of Jamaica in 1655 and successful attacks on Spanish treasure fleets in 1656 and 1657, but also the devastation of English merchant shipping by the privateers of Dunkirk, until their home port was captured by Anglo-French forces in 1658.[56]

(Jan_Abrahamsz._Beerstraten).jpg)

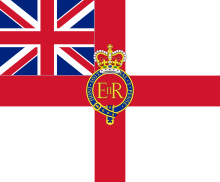

The Restoration of the English monarchy occurred in May 1660, and Charles II assumed the throne. One of his first acts was to officially name the Royal Navy, The prefix HMS was also officially attached to its vessels for the first time. Nevertheless, the navy remained a national institution, rather than the personal possession of the reigning monarch, as it had been before the civil war.[57]

As a result of their defeat in the First Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch transformed their navy, largely abandoning the use of militarised merchantmen and establishing a fleet composed mainly of heavily armed, purpose-built warships, as the English had done previously. Consequently, the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667) was a closely fought struggle between evenly matched opponents, with English victory at Lowestoft (1665) countered by Dutch triumph in the epic Four Days' Battle (1666).[58] The deadlock was broken not by combat but by the superiority of Dutch public finance, as in 1667 Charles II was forced to lay up the fleet in port for lack of money to keep it at sea while negotiating for peace. Disaster followed as the Dutch fleet mounted the Raid on the Medway, breaking into Chatham Dockyard and capturing or burning many of the Navy's largest ships at their moorings.[59] In the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), Charles II allied with Louis XIV of France against the Dutch, but the combined Anglo-French fleet was fought to a standstill in a series of inconclusive battles, while the French invasion by land was warded off.[60]

.jpg)

During the 1670s and 1680s, the English Royal Navy succeeded in permanently ending the threat to English shipping from the Barbary corsairs, inflicting defeats which induced the Barbary states to conclude long-lasting peace treaties.[61] Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, England joined the European coalition against Louis XIV in the War of the Grand Alliance (1688–1697). Louis' recent shipbuilding programme had given France the largest navy in Europe. A combined Anglo-Dutch fleet was defeated at Beachy Head (1690), but victory at Barfleur-La Hogue (1692) was a turning-point, marking the end of France's brief pre-eminence at sea and the beginning of an enduring English, later British, supremacy.[62]

In the course of the 17th century, the English Royal Navy completed the transition from a semi-amateur Navy Royal fighting in conjunction with private vessels into a fully professional institution. Its financial provisions were gradually regularised, it came to rely on dedicated warships only, and it developed a professional officer corps with a defined career structure, superseding an earlier mix of "gentlemen" (upper-class soldiers) and "tarpaulins" (professional seamen, who generally served on merchant or fishing vessels in peacetime).[63]

James IV put the Royal Scots Navy on a new footing, founding a harbour at Newhaven in May 1504, and two years later ordering the construction of a dockyard at the Pools of Airth. The upper reaches of the Forth were protected by new fortifications on Inchgarvie.[64] Scottish ships had some success against privateers, accompanied the king in his expeditions in the islands and intervened in conflicts in Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea.[35] Expeditions to the Highlands to Islands to curb the power of the MacDonald Lord of the Isles were largely ineffective until in 1504 the king accompanied a squadron under Wood heavily armed with artillery, which battered the MacDonald strongholds into submission. Since some of these island fortresses could only be attacked from seaward, naval historian N. A. M. Rodger has suggested this may have marked the end of medieval naval warfare in the British Isles, ushering in a new tradition of artillery warfare.[37] The king acquired a total of 38 ships for the Royal Scottish Navy, including Margaret, and the carrack Michael or Great Michael, the largest warship of its time (1511).[65] The latter, built at great expense at Newhaven and launched in 1511, was 240 feet (73 m) in length, weighed 1,000 tons, had 24 cannon, and was, at that time, the largest ship in Europe.[65][66] It marked a shift in design as it was crafted specifically to carry a main armament of heavy artillery.[37]

During the Rough Wooing, the attempt to force a marriage between James V's heir Mary, Queen of Scots and Henry VIII's son, the future Edward VI, in 1542, Mary Willoughby, Lion, and Salamander under the command of John Barton, son of Robert Barton, attacked merchants and fishermen off Whitby. They later blockaded a London merchant ship called Antony of Bruges in a creek on the coast of Brittany.[67] In 1544, Edinburgh was attacked by an English marine force and burnt. Salamander and the Scottish-built Unicorn were captured at Leith. The Scots still had two royal naval vessels and numerous smaller private vessels.[68]

When, as a result of the series of international treaties, Charles V declared war upon Scotland in 1544, the Scots were able to engage in a highly profitable campaign of privateering that lasted six years and the gains of which probably outweighed the losses in trade with the Low Countries.[69]

The Scots operated in the West Indies from the 1540s, joining the French in the capture of Burburuta in 1567.[70] English and Scottish naval warfare and privateering broke out sporadically in the 1550s.[71] When Anglo-Scottish relations deteriorated again in 1557 as part of a wider war between Spain and France, small ships called 'shallops' were noted between Leith and France, passing as fishermen, but bringing munitions and money. Private merchant ships were rigged at Leith, Aberdeen and Dundee as men-of-war, and the regent Mary of Guise claimed English prizes, one over 200 tons, for her fleet.[72] The re-fitted Mary Willoughby sailed with 11 other ships against Scotland in August 1557, landing troops and six field guns on Orkney to attack the Kirkwall Castle, St Magnus Cathedral and the Bishop's Palace. The English were repulsed by a Scottish force numbering 3000, and the English vice-admiral Sir John Clere of Ormesby was killed, but none of the English ships were lost.[73]

After the Union of Crowns in 1603 conflict between Scotland and England ended, but Scotland found itself involved in England's foreign policy, opening up Scottish shipping to attack. In the 1620s, Scotland found herself fighting a naval war as England's ally, first against Spain and then also against France, while simultaneously embroiled in undeclared North Sea commitments in the Danish intervention in the Thirty Years' War. In 1626 a squadron of three ships was bought and equipped, at a cost of least £5,200 sterling, to guard against privateers operating out of Spanish-controlled Dunkirk and other ships were armed in preparation for potential action.[66] The acting High Admiral John Gordon of Lochinvar organized as many as three marque fleets of privateers.[74] It was probably one of Lochinvar's marque fleets that was sent to support the English Royal Navy in defending Irish waters in 1626.[75] In 1627, the Royal Scots Navy and accompanying contingents of burgh privateers participated in the major expedition to Biscay.[76] The Scots also returned to the West Indies, with Lochinvar taking French prizes and founding the colony of Charles Island.[70] In 1629, two squadrons of privateers led by Lochinvar and William Lord Alexander, sailed for Canada, taking part in the campaign that resulted in the capture of Quebec from the French, which was handed back after the subsequent peace.[77]

By 1697 the English Royal Navy had 323 warships, while Scotland was still dependent on merchantman and privateers. In the 1690s, two separate schemes for larger naval forces were put in motion. As usual, the larger part was played by the merchant community rather than the government. The first was the Darien Scheme to found a Scottish colony in Spanish controlled America. It was undertaken by the Company of Scotland, who created a fleet of five ships, including Caledonia and St. Andrew, all built or chartered in Holland and Hamburg. It sailed to the Isthmus of Darien in 1698, but the venture failed and only one ship returned to Scotland.[78] In the same period, it was decided to establish a professional navy for the protection of commerce in home waters during the Nine Years' War (1688–1697) with France, with three purpose-built warships bought from English shipbuilders in 1696. These were Royal William, a 32-gun fifth rate and two smaller ships, Royal Mary and Dumbarton Castle, each of 24 guns, generally described as frigates.[79]

Britain's navy in the early modern period 1707–1815

The Acts of Union, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707, established the Royal Navy of the newly united kingdom. The Scots office of Lord High Admiral was subsumed within the office of the Admiral of Great Britain.[36] The three vessels of the small Royal Scottish Navy were transferred to the Royal Navy.[79]

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the Royal Navy was the largest maritime force in the world, but until 1805 combinations of enemies repeatedly matched or exceeded its forces in numbers.[80] Despite this, it was able to maintain an almost uninterrupted ascendancy over its rivals through superiority in financing, tactics, training, organisation, social cohesion, hygiene, dockyard facilities, logistical support and (from the middle of the 18th century) warship design and construction.[81]

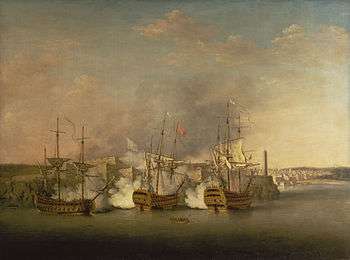

During the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1714), the Navy operated in conjunction with the Dutch against the navies of France and Spain, in support of the efforts of Britain's Austrian Habsburg allies to seize control of Spain and its Mediterranean dependencies from the Bourbons. Amphibious operations by the Anglo-Dutch fleet brought about the capture of Sardinia, the Balearic Islands and a number of Spanish mainland ports, most importantly Barcelona. While most of these gains were turned over to the Habsburgs, Britain held on to Gibraltar and Menorca, which were retained in the peace settlement, providing the Navy with Mediterranean bases. Early in the war French naval squadrons had done considerable damage to English and Dutch commercial convoys. However, a major victory over France and Spain at Vigo Bay (1702), further successes in battle, and the scuttling of the entire French Mediterranean fleet at Toulon in 1707 virtually cleared the Navy's opponents from the seas for the latter part of the war. Naval operations also enabled the conquest of the French colonies in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.[82] Further conflict with Spain followed in the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720), in which the Navy helped thwart a Spanish attempt to regain Sicily and Sardinia from Austria and Savoy, defeating a Spanish fleet at Cape Passaro (1718), and in an undeclared war in the 1720s, in which Spain tried to retake Gibraltar and Menorca.[83]

After a period of relative peace, the Navy became engaged in the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–1748) against Spain, which was dominated by a series of costly and mostly unsuccessful attacks on Spanish ports in the Caribbean, primarily a huge expedition against Cartagena de Indias in 1741. These led to heavy loss of life from tropical diseases.[84][85][86] In 1742 the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was driven to withdraw from the war in the space of half an hour by the threat of a bombardment of its capital Naples by a small British squadron. The war became subsumed in the wider War of the Austrian Succession (1744–1748), once again pitting Britain against France. Naval fighting in this war, which for the first time included major operations in the Indian Ocean, was largely inconclusive, the most significant event being the failure of an attempted French invasion of England in 1744.[87]

Total naval losses in the War of the Austrian Succession, including ships lost in storms and in shipwrecks were: France—20 ships-of-the-line, 16 frigates, 20 smaller ships, 2,185 merchantmen, 1,738 guns; Spain—17 ships-of-the-line, 7 frigates, 1,249 merchantmen, 1,276 guns; Britain—14 ships-of-the-line, 7 frigates, 28 smaller ships, 3,238 merchantmen, 1,012 guns. Personnel losses at sea were about 12,000 killed, wounded, or taken prisoner for France, 11,000 for Spain, and 7,000 for Britain.[88]

The subsequent Seven Years' War (1756–1763) saw the Navy conduct amphibious campaigns leading to the conquest of New France, of French colonies in the Caribbean and West Africa, and of small islands off the French coast, while operations in the Indian Ocean contributed to the destruction of French power in India.[89] A new French attempt to invade Britain was thwarted by the defeat of their escort fleet in the extraordinary Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759, fought in a gale on a dangerous lee shore. Once again the British fleet effectively eliminated the French Navy from the war, leading France to abandon major operations.[90] In 1762 the resumption of hostilities with Spain led to the British capture of Manila and of Havana, along with a Spanish fleet sheltering there.[91]

Naval losses of the Seven Years' War testify to the extent of the British victory. France lost 20 of her ships-of-the-line captured and 25 sunk, burned, destroyed, or lost in storms. The French navy also lost 25 frigates captured and 17 destroyed, and suffered casualties of 20,000 killed, drowned, or missing, as well as another 20,000 wounded or captured. Spain lost 12 ships-of-the-line captured or destroyed, 4 frigates, and 10,000 seamen killed, wounded, or captured. The Royal Navy lost 2 ships-of-the-line captured, 17 sunk or destroyed by either battle or storm, 3 frigates captured and 14 sunk, but added 40 ships-of-the-line during the course of the war. British crews suffered 20,000 casualties, including POWs. Actual naval combat deaths for Britain were only 1,500, but the figure of 133,708 is given for those who died of sickness or deserted.[92]

In the American War of Independence (1775–1783) the Royal Navy readily obliterated the small Continental Navy of frigates fielded by the rebel colonists, but the entry of France, Spain and the Netherlands into the war against Britain produced a combination of opposing forces which deprived the Navy of its position of superiority for the first time since the 1690s, briefly but decisively. The war saw a series of inconclusive battles in the Atlantic and Caribbean, in which the Navy failed to achieve the decisive victories needed to secure the supply lines of British forces in North America and to cut off the colonial rebels from outside support.[93] The most important operation of the war came in 1781 when, in the Battle of the Chesapeake, the British fleet failed to lift the French blockade of Lord Cornwallis's army, resulting in Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown.[94] Although this disaster effectively concluded the fighting in North America, hostilities continued in the Indian Ocean, where the French were prevented from re-establishing a meaningful foothold in India, and in the Caribbean. British victory in the Caribbean in the Battle of the Saintes in 1782 and the relief of Gibraltar later the same year symbolised the restoration of British naval ascendancy, but this came too late to prevent the independence of the rebellious Thirteen Colonies.[95]

The eradication of scurvy from the Royal Navy in the 1790s came about due to the efforts of Gilbert Blane, chairman of the Navy's Sick and Hurt Board, which ordered fresh lemon juice to be given to sailors on ships. Other navies soon adopted this successful solution.[96]

The French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1801) and Napoleonic Wars (1803–1814 and 1815) saw the Royal Navy reach a peak of efficiency, dominating the navies of all Britain's adversaries, which spent most of the war blockaded in port. The Navy achieved an emphatic early victory at the Glorious First of June (1794) and gained a number of smaller victories while supporting abortive French Royalist efforts to regain control of France. In the course of one such operation, the majority of the French Mediterranean fleet was captured or destroyed during a short-lived occupation of Toulon in 1793.[97] The military successes of the French Revolutionary régime brought the Spanish and Dutch navies into the war on the French side, but the losses inflicted on the Dutch at the Battle of Camperdown in 1797 and the surrender of their surviving fleet to a landing force at Den Helder in 1799 effectively eliminated the Dutch navy from the war.[98] The Spithead and Nore mutinies in 1797 incapacitated the Channel and North Sea fleets, leaving Britain potentially exposed to invasion, but were rapidly resolved.[99] The British Mediterranean fleet under Horatio Nelson failed to intercept Napoleon Bonaparte's 1798 expedition to invade Egypt, but annihilated the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile, leaving Bonaparte's army isolated.[100] The emergence of a Baltic coalition opposed to Britain led to an attack on Denmark, which lost much of its fleet in the Battle of Copenhagen (1801) and came to terms with Britain.[101]

During these years, the Navy also conducted amphibious operations that captured most of the French Caribbean islands and the Dutch colonies at the Cape of Good Hope and Ceylon. Though successful in their outcome, the expeditions to the Caribbean, conducted on a grand scale, led to devastating losses from disease. Except for Ceylon and Trinidad, these gains were returned following the Peace of Amiens in 1802, which briefly halted the fighting.[102] Menorca, which had been repeatedly lost and regained during the 18th century, was restored to Spain, its place as the Navy's main base in the Mediterranean being taken by the new acquisition of Malta. War resumed in 1803 and Napoleon attempted to assemble a large enough fleet from the French and Spanish squadrons blockaded in various ports to cover an invasion of England. The Navy frustrated these efforts, and following the abandonment of the invasion plan, Nelson defeated the combined Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar (1805).[103]

After Trafalgar, large-scale fighting at sea remained limited to the destruction of small, fugitive French squadrons, and amphibious operations which again captured the colonies which had been restored at Amiens, along with France's Indian Ocean base at Mauritius and parts of the Dutch East Indies, including Java and the Moluccas.[104] In 1807, French plans to seize the Danish fleet led to a pre-emptive British attack on Copenhagen, resulting in the surrender of the entire Danish navy.[105] The impressment of British and American sailors from American ships contributed to the outbreak of the War of 1812 (1812–1814) against the United States, in which the naval fighting was largely confined to commerce raiding and a series of single-ship actions, usually won by America.[106] The brief renewal of war after Napoleon's return to power in 1815 did not bring a resumption of naval combat.[107]

1815–1914

Between 1815 and 1914, the Navy saw little serious action, owing to the absence of any opponent strong enough to challenge its dominance. During this period, naval warfare underwent a comprehensive transformation, brought about by steam propulsion, metal ship construction, and explosive munitions. Despite having to completely replace its war fleet, the Navy managed to maintain its overwhelming advantage over all potential rivals. Due to British leadership in the Industrial Revolution, the country enjoyed unparalleled shipbuilding capacity and financial resources, which ensured that no rival could take advantage of these revolutionary changes to negate the British advantage in ship numbers.[108]

_(11632529933).jpg)

In 1859, the fleet was estimated to number about 1000 in all, including both combat and non-combat vessels.[109] In 1889, Parliament passed the Naval Defence Act, which formally adopted the 'two-power standard', which stipulated that the Royal Navy should maintain a number of battleships at least equal to the combined strength of the next two largest navies.[110]

The first major action that the Royal Navy saw during this period was the Bombardment of Algiers in 1816 by a joint Anglo-Dutch fleet under Lord Exmouth, to force the Barbary state of Algiers to free Christian slaves and to halt the practice of enslaving Europeans. During the Greek War of Independence, the combined navies of Britain, France and Russia defeated an Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Navarino in 1827, the last major action between sailing ships. During the same period, the Royal Navy took anti-piracy actions in the South China Sea.[111] Between 1807 and 1865, it maintained a Blockade of Africa to counter the illegal slave trade. It also participated in the Crimean War of 1854–56, as well as numerous military actions throughout Asia and Africa, notably the First and Second Opium Wars with Qing dynasty China. On 27 August 1896, the Royal Navy took part in the Anglo-Zanzibar War, which was the shortest war in history.[112]

The end of the 19th century saw structural changes brought about by the First Sea Lord Jackie Fisher, who retired, scrapped or placed into reserve many of the older vessels, making funds and manpower available for newer ships. He also oversaw the development of HMS Dreadnought, launched in 1906. Its speed and firepower rendered all existing battleships obsolete. The industrial and economic development of Germany had by this time overtaken Britain, enabling the Imperial German Navy to attempt to outpace British construction of dreadnoughts. In the ensuing arms race, Britain succeeded in maintaining a substantial numerical advantage over Germany, but for the first time since 1805 another navy now existed with the capacity to challenge the Royal Navy in battle.[113]

Reforms were also gradually introduced in the conditions for enlisted men with the abolition of military flogging in 1879, amongst others.[114]

1914–1939

During the First World War, the Royal Navy's strength was mostly deployed at home in the Grand Fleet, confronting the German High Seas Fleet across the North Sea. Several inconclusive clashes took place between them, chiefly the Battle of Jutland in 1916. The British numerical advantage proved insurmountable, leading the High Seas Fleet to abandon any attempt to challenge British dominance.[115]

Elsewhere in the world, the Navy hunted down the handful of German surface raiders at large. During the Dardanelles Campaign against the Ottoman Empire in 1915, it suffered heavy losses during a failed attempt to break through the system of minefields and shore batteries defending the straits.[116]

Upon entering the war, the Navy had immediately established a blockade of Germany. The Navy's Northern Patrol closed off access to the North Sea, while the Dover Patrol closed off access to the English Channel. The Navy also mined the North Sea. As well as closing off the Imperial German Navy's access to the Atlantic, the blockade largely blocked neutral merchant shipping heading to or from Germany. The blockade was maintained during the eight months after the armistice was agreed to force Germany to end the war and sign the Treaty of Versailles.[117]

The most serious menace faced by the Navy came from the attacks on merchant shipping mounted by German U-boats. For much of the war this submarine campaign was restricted by prize rules requiring merchant ships to be warned and evacuated before sinking. In 1915, the Germans renounced these restrictions and began to sink merchant ships on sight, but later returned to the previous rules of engagement to placate neutral opinion. A resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917 raised the prospect of Britain and its allies being starved into submission. The Navy's response to this new form of warfare had proved inadequate due to its refusal to adopt a convoy system for merchant shipping, despite the demonstrated effectiveness of the technique in protecting troopships. The belated introduction of convoys sharply reduced losses and brought the U-boat threat under control.[118]

In the inter-war period, the Royal Navy was stripped of much of its power. The Washington and London Naval Treaties imposed the scrapping of some capital ships and limitations on new construction.[119] In 1932, the Invergordon Mutiny took place over a proposed 25% pay cut, which was eventually reduced to 10%.[120] International tensions increased in the mid-1930s and the Second London Naval Treaty of 1935 failed to halt the development of a naval arms race. By 1938, treaty limits were effectively being ignored. The re-armament of the Royal Navy was well under way by this point; the Royal Navy had begun construction of the still treaty-affected new battleships and its first full-sized purpose-built aircraft carriers. In addition to new construction, several existing old battleships, battlecruisers and heavy cruisers were reconstructed, and anti-aircraft weaponry reinforced, while new technologies, such as ASDIC, Huff-Duff and hydrophones, were developed. The Navy had lost control of naval aviation when the Royal Naval Air Service was merged with the Royal Flying Corps to form the Royal Air Force in 1918, but regained control of ship-board aircraft with the return of the Fleet Air Arm to Naval control in 1937.[121]

1939–1945

At the start of World War II in 1939, the Royal Navy was the largest in the world, with over 1,400 vessels, including:[122][123]

- 7 aircraft carriers – with 5 more under construction

- 15 battleships and battlecruisers – with 5 more under construction

- 66 cruisers – with 23 more under construction

- 184 destroyers – with 52 under construction

- 45 escort and patrol vessels – with 9 under construction and one on order

- 60 submarines – with 9 under construction

During one of the earliest phases of the War the Royal Navy provided critical cover during Operation Dynamo, the British evacuations from Dunkirk, and as the ultimate deterrent to a German invasion of Britain during the following four months. At Taranto, Admiral Cunningham commanded a fleet that launched the first all-aircraft naval attack in history. Cunningham was determined that the Navy be perceived as the United Kingdom's most daring military force: when warned of risks to his vessels during the Allied evacuation after the Battle of Crete he said, "It takes the Navy three years to build a new ship. It will take three hundred years to build a new tradition. The evacuation will continue."[124]

The Royal Navy suffered heavy losses in the first two years of the war, including the carriers Courageous, Glorious and Ark Royal, the battleships Royal Oak and Barham and the battlecruiser Hood in the European Theatre, and the carrier Hermes, the battleship Prince of Wales, the battlecruiser Repulse and the heavy cruisers Exeter, Dorsetshire and Cornwall in the Asian Theatre. Of the 1,418 men aboard Hood, only three survived its sinking.[125] Over 3,000 people were lost when the converted troopship Lancastria was sunk in June 1940, the greatest maritime disaster in Britain's history.[126] There were however also successes against enemy surface ships, as in the battles of the River Plate in 1939, Narvik in 1940 and Cape Matapan in 1941, and the sinking of the German capital ships Bismarck in 1941 and Scharnhorst in 1943.[127]

.jpg)

The Navy's most critical struggle was the Battle of the Atlantic defending Britain's vital commercial supply lines against U-boat attack. A traditional convoy system was instituted from the start of the war, but German submarine tactics, based on group attacks by "wolf-packs", were much more effective than in the previous war, and the threat remained serious for well over three years. Defences were strengthened by deployment of purpose-built escorts, of escort carriers, of long-range patrol aircraft, improved anti-submarine weapons and sensors, and by the deciphering of German signals by the code-breakers of Bletchley Park. The threat was at last effectively broken by devastating losses inflicted on the U-boats in the spring of 1943. Intense convoy battles of a different sort, against combined air, surface and submarine threats, were fought off enemy-controlled coasts in the Arctic, where Britain ran supply convoys through to Russia, and in the Mediterranean, where the struggle focused on Convoys to Malta.[128]

The Navy was also vital in guarding the sea lanes that enabled British forces to fight in North Africa, the Mediterranean and the Far East. Naval supremacy was essential to amphibious operations such as the invasions of Northwest Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Normandy. By the end of the war the Royal Navy comprised over 4,800 ships, and was the second-largest fleet in the world.[129]

Postwar period and early 21st century

After the Second World War, the decline of the British Empire and the economic hardships in Britain forced the reduction in the size and capability of the Royal Navy. All of the pre-war ships (except for the Town-class light cruisers) were quickly retired and most sold for scrapping over the years 1945–1948, and only the best condition ships (the four surviving King George V-class battleships, carriers, cruisers, and some destroyers) were retained and refitted for service. The increasingly powerful United States Navy took on the former role of the Royal Navy as a global naval power and police force of the sea. The combination of the threat of the Soviet Union, and Britain's commitments throughout the world, created a new role for the Navy. Governments since the Second World War have had to balance commitments with increasing budgetary pressures, partly due to the increasing cost of weapons systems, what historian Paul Kennedy called the Upward Spiral.[130]

These pressures were exacerbated by bitter inter-service rivalry. A modest new construction programme was initiated with some new carriers (Majestic- and Centaur-class light carriers, and Audacious-class large carriers, such as HMS Ark Royal, being completed between 1948 through 1958), along with three Tiger-class cruisers (completed 1959–1961), the Daring-class destroyers in the 1950s, and finally the County-class guided missile destroyers completed in the 1960s.[131]

HMS Dreadnought, the Royal Navy's first nuclear submarine, was launched in the 1960s. The navy also received its first nuclear weapons with the introduction of the first of the Resolution-class submarines armed with the Polaris missile. The introduction of Polaris followed the cancellation of the GAM-87 Skybolt missile which had been proposed for use by the Air Force's V bomber force. By the 1990s, the navy became responsible for the maintenance of the UK's entire nuclear arsenal. The financial costs attached to nuclear deterrence became an increasingly significant issue for the navy.[132]

The Navy began plans to replace its fleet of aircraft carriers in the mid-1960s. A plan was drawn up for three large aircraft carriers, each displacing about 60,000 tons; the plan was designated CVA-01. These carriers would be able to operate the latest aircraft coming into service and keep the Royal Navy's place as a major naval power. The new Labour government that came to power in 1964 was determined to cut defence expenditure as a means to reduce public spending, and in the 1966 Defence White Paper the project was cancelled.[133] The existing carriers (all built during, or just after World War II) were refitted, two (Bulwark and Albion) becoming commando carriers, and four (Victorious, Eagle, and Ark Royal) being completed or rebuilt. Starting in 1965 with Centaur, one by one these carriers were decommissioned without replacement, culminating with the 1979 retirement of Ark Royal. By the early 1980s, only Hermes survived and received a refit (just in time for the Falklands War), to operate Sea Harriers. She operated along with three much smaller Invincible-class aircraft carriers, and the fleet was now centred around anti-submarine warfare in the north Atlantic as opposed to its former position with worldwide strike capability. Along with the war era carriers, all of the war built cruisers and destroyers, along with the post-war built Tiger-class cruisers and large County-class guided-missile destroyers were either retired or sold by 1984.[134]

The Royal Navy was involved in three major confrontations with the Icelandic Coast Guard from 1958 to 1976. These largely bloodless incidents became known as the Cod Wars.[135] One of the most important operations conducted predominantly by the Royal Navy after the Second World War was the 1982 defeat of Argentina in the Falkland Islands War. Despite losing four naval ships and other civilian and RFA ships, the Royal Navy fought and won a war over 8,000 miles (12,000 km) from Great Britain. HMS Conqueror is the only nuclear-powered submarine to have engaged an enemy ship with torpedoes, sinking the cruiser ARA General Belgrano.[136]

Before the Falklands War, Defence Secretary John Nott had advocated and initiated a series of cutbacks to the Navy.[137] The Falklands War though, provided a reprieve in Nott-proposed cutbacks, and proved a need for the Royal Navy to regain an expeditionary and littoral capability which, with its resources and structure at the time, would prove difficult. At the beginning of the 1980s, the Royal Navy was a force focused on blue-water anti-submarine warfare. Its purpose was to search for and destroy Soviet submarines in the North Atlantic, and to operate the nuclear deterrent submarine force. For a time Hermes was retained, along with all three of the Invincible-class light aircraft carriers. More Sea Harriers were ordered; not just to replace losses, but to also increase the size of the Fleet Air Arm. New and more capable ships were built; notably the Sheffield-class destroyers, the Type 21, Type 22, and Type 23 frigates, new LPDs of the Albion class, and HMS Ocean, but never in the numbers of the ships that they replaced. As a result, the Royal Navy surface fleet continues to reduce in size. A 2013 report found that the current RN was already too small, and that Britain would have to depend on her allies if her territories were attacked.[138]

The Royal Navy also took part in the Gulf War, the Kosovo conflict, the Afghanistan Campaign, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the last of which saw RN warships bombard positions in support of the Al Faw Peninsula landings by Royal Marines. In August 2005, the Royal Navy rescued seven Russians stranded in a submarine off the Kamchatka peninsula. The Navy's Scorpio 45 remote-controlled mini-sub freed the Russian submarine from the fishing nets and cables that had held it for three days. The Royal Navy was also involved in an incident involving Somali pirates in November 2008, after the pirates tried to capture a civilian vessel.[139]

The global economic recession of 2008 had a significant impact on the Royal Navy resulting in the Strategic Defence and Security Review 2010 which made sweeping cuts to the Navy's budget. The Harrier aircraft were retired with some being presented to museums and the rest being sold to the United States for spare parts to keep their aircraft flying. The carrier Ark Royal and the remaining Type 22 frigates were all removed from service and sold for scrap. HMS Illustrious however, was retained through to 2014 in the LPH role, until Ocean completed her refit. Plans were made to allow Illustrious to be retained as a floating museum, but by summer of 2016 she too was sold for scrap.[140] The future of Albion and Bulwark is uncertain as funds may not be available to allow them to remain in service.[141] The Royal Navy was to receive 12 Type 45 destroyers as a replacement for the older Type 42 class that was completely retired by 2013. The number was later reduced to 6 vessels, all in service by 2012.[142]

In 2015, the Royal Navy was deployed to the Mediterranean in the mission to rescue migrants crossing the Mediterranean from Libya to Italy.[143] By spring 2018, the Royal Navy had decommissioned HMS Ocean, as well as started the replacement of the River-class offshore patrol vessels. The first of the new Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers was undergoing tests and workups before her first fixed-wing aircraft arrive later in the year, and design work was underway for the new generation of nuclear deterrent submarines.[144] By July 2017 the first of 8 new frigates was laid down, the Type 26 frigate.[145]

Royal Navy today

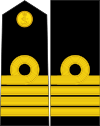

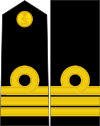

Personnel

HMS Raleigh at Torpoint, Cornwall, is the basic training facility for newly enlisted ratings. Britannia Royal Naval College is the initial officer training establishment for the navy, located at Dartmouth, Devon. Personnel are divided into a warfare branch, which includes warfare officers (previously named seamen officers) and Naval Aviators,[146] as well other branches including the Royal Naval Engineers, Royal Navy Medical Branch, and Logistics Officers, the renamed Supply Officer branch. Present-day officers and ratings have several different Royal Navy uniforms; some are designed to be worn aboard ship, others ashore or in ceremonial duties. Women began to join the Royal Navy in 1917 with the formation of the Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS), which was disbanded after the end of the First World War in 1919. It was revived in 1939, and the WRNS continued until disbandment in 1993, as a result of the decision to fully integrate women into the structures of the Royal Navy. Women now serve in all sections of the Royal Navy including the Royal Marines.[147]

By January 2015, the Naval Service (Royal Navy and Royal Marines) numbered some 32,880 Regular[148] and 3,040 Maritime Reserve personnel (Royal Naval Reserve and Royal Marines Reserve),[149] giving a combined component strength of 35,920 personnel. In addition to the active elements of the Naval Service (Regular and Maritime Reserve), all ex-Regular personnel remain liable to be recalled for duty in a time of need, this is known as the Regular Reserve. In 2002, there were 26,520 Regular Reserves of the Naval Service, of which 13,720 served in the Royal Fleet Reserve.[150] Publications since April 2013 no-longer report the entire strength of the Regular Reserve, instead they only give a figure for Regular Reserves who serve in the Royal Fleet Reserve.[151] They had a strength of 7,960 personnel in 2013.[152]

In August 2019, the Ministry of Defence published figures showing that the Royal Navy and Royal Marines had 29,090 full-time trained personnel compared with a target of 30,600.[153]

In December 2019 the First Sea Lord, Admiral Tony Radakin outlined a proposal to reduce the number of Rear-Admirals at Navy Command by five.[154] The fighting arms (excluding Commandant General Royal Marines) would be reduced to Commodore (1-star) rank and the surface flotillas would be combined together. Training would be concentrated under the Fleet Commander.[155]

Surface fleet

_underway_during_trials_with_HMS_Sutherland_(F81)_and_HMS_Iron_Duke_(F234)_on_28_June_2017_(45162784).jpg)

Amphibious warfare

The large fleet units in the Royal Navy consisted of amphibious warfare ships until December 2017, when the first Queen Elizabeth-class carrier was commissioned.[156] Amphibious warfare ships in current service include two landing platform docks (HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark). While their primary role is to conduct amphibious warfare, they have also been deployed for humanitarian aid missions.[157]

Aircraft carriers

The Royal Navy has two Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers, currently undertaking sea and aircraft trials which are both due to enter naval service within the next few years. These carriers cost £6 billion and displace 65,000 tonnes (64,000 long tons; 72,000 short tons)[158] The first, HMS Queen Elizabeth commenced flight trials in 2018. Both are intended to operate the STOVL variant of the F-35 Lightning II. Queen Elizabeth began sea trials in June 2017, was commissioned later that year, and will enter service in 2020, while the second, HMS Prince of Wales began sea trials on 22 September 2019, was commissioned in December 2019 and is due to enter service in 2023.[159][160][161][162]

Escort fleet

The escort fleet comprises guided missile destroyers and frigates and is the traditional workhorse of the Navy.[163] As of January 2018 there are six Type 45 destroyers and 13 Type 23 frigates in active service. Among their primary roles is to provide escort for the larger capital ships—protecting them from air, surface and subsurface threats. Other duties include undertaking the Royal Navy's standing deployments across the globe, which often consists of: counter-narcotics, anti-piracy missions and providing humanitarian aid.[157]

All six Type 45 destroyers have been built and are in commission, with HMS Duncan being the last and final Type 45 entering service in September 2013.[164] The new Type 45 destroyers replaced the older Type 42 destroyers. The Type 45 is primarily designed for anti-aircraft and anti-missile warfare and the Royal Navy describe the destroyers mission as "to shield the Fleet from air attack".[165] They are equipped with the PAAMS (also known as Sea Viper) integrated anti-aircraft warfare system which incorporates the sophisticated SAMPSON and S1850M long range radars and the Aster 15 and 30 missiles.[166]

Initially, 16 Type 23 frigates were delivered to the Royal Navy, with the final vessel, HMS St Albans, commissioned in June 2002. However, the 2004 review of defence spending (Delivering Security in a Changing World) announced that three frigates of the fleet of sixteen would be paid off as part of a continuous cost-cutting strategy, and these were subsequently sold to the Chilean Navy.[167] The 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review announced that the remaining 13 Type 23 frigates would eventually be replaced by the Type 26 Frigate.[168] The Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 reduced the procurement of Type 26 to eight with five Type 31e frigates to be procured.[169]

Mine Countermeasure Vessels (MCMV)

There are two classes of MCMVs in the Royal Navy: seven Sandown-class minehunters and six Hunt-class mine countermeasures vessels. The Hunt-class vessels combine the separate roles of the traditional minesweeper and the active minehunter in one hull. If required, the Sandown and Hunt-class vessels can take on the role of offshore patrol vessels.[170]

Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPV)

In 1997, three Batch 1 River class ships were procured; unusually, these were owned by Vosper Thorneycroft, and leased to the Royal Navy until 2013. This relationship was defined by a ground-breaking contractor logistic support contract which contracts the ships' availability to the RN, including technical and stores support. In November 2013, it was announced that in order to sustain shipbuilding capabilities on the Clyde, five new ocean-going patrol vessels with Merlin-capable flight decks would be ordered for delivery from 2017. These ‘Batch 2’ ships will replace the four existing River-class ships.[171] In October 2014, the Ministry of Defence announced the names of the first three ships as HMS Forth, HMS Medway and HMS Trent.[172] The fourth and fifth ships were ordered in December 2016: these will be named HMS Tamar and HMS Spey.[173]

In December 2019, the modified ‘Batch 1’ River-class vessel, HMS Clyde, was decommissioned, with the ‘Batch 2’ HMS Forth taking over duties as the Falkland Islands patrol ship.[174][175]

Ocean survey ships

HMS Protector is a dedicated Antarctic patrol ship that fulfils the nation's mandate to provide support to the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).[176]HMS Scott is an ocean survey vessel and at 13,500 tonnes is one of the largest ships in the Navy. The other survey vessels of the Royal Navy are the two multi-role ships of the Echo class, which came into service in 2002 and 2003. As of 2018, the newly commissioned HMS Magpie also undertakes survey duties at sea.[177]

Royal Fleet Auxiliary

The Navy's large fleet units are supported by the Royal Fleet Auxiliary which possesses three amphibious transport docks within its operational craft. These are known as the Bay-class landing ships, of which four were introduced in 2006–2007, but one was sold to the Royal Australian Navy in 2011.[178] In November 2006, the First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Jonathon Band described the Royal Fleet Auxiliary vessels as "a major uplift in the Royal Navy's war fighting capability".[179]

Submarine Service

The Submarine Service is the submarine based element of the Royal Navy. It is sometimes referred to as the "Silent Service",[180] as the submarines are generally required to operate undetected. Founded in 1901, the service made history in 1982 when, during the Falklands War, HMS Conqueror became the first nuclear-powered submarine to sink a surface ship, ARA General Belgrano. Today, all of the Royal Navy's submarines are nuclear-powered.[181]

Ballistic Missile Submarines (SSBN)

The Royal Navy operates four Vanguard class ballistic missile submarines displacing nearly 16,000 tonnes and equipped with Trident II missiles (armed with nuclear weapons) and heavyweight Spearfish torpedoes, with the purpose to carry out Operation Relentless, the United Kingdom's Continuous At Sea Deterrent (CASD). In December 2006, the Government published recommendations for a new class of four ballistic missile submarines to replace the current Vanguard class, starting 2024. These new Dreadnought-class submarines will mean that the United Kingdom will maintain a nuclear ballistic missile submarine fleet and the ability to launch nuclear weapons.[182]

Fleet Submarines (SSN)

Six fleet submarines are presently in service, with three Trafalgar class and three Astute class (with the remainder in construction) making up the total. The Trafalgar class displace little over 5,300 tonnes when submerged and are armed with Tomahawk land-attack missiles and Spearfish torpedoes. The Astute class at 7,400 tonnes[183] are much larger and carry a larger number of Tomahawk missiles and Spearfish torpedoes. Four more Astute-class fleet submarines are expected to be commissioned and will eventually replace the remaining Trafalgar-class boats. HMS Artful was the latest Astute-class boat to be commissioned.[184]

In the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review, the UK Government reaffirmed its intention to procure seven Astute-class submarines.[185]

Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is the branch of the Royal Navy responsible for the operation of naval aircraft, it can trace its roots back to 1912 and the formation of the Royal Flying Corps. The Fleet Air Arm currently comprises: Commando Helicopter Force (operating the AW-101 Merlin HC4 in support of 3 Commando Brigade), Maritime Wildcat Force (operating the AW-159 Wildcat HM2 on small ship's flights), Merlin Force (operating the AW-101 Merlin HM2 in an anti-submarine role) and the newly formed Lightning Force (operating the F-35B Lightning II in the maritime strike role).[186]

Pilots designated for rotary wing service train under No. 1 Flying Training School (1 FTS)[187] at RAF Shawbury.[188]

The FAA is undergoing F-35B (Lightning II) aviation trials on board the new Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers[189] following the retirement of Joint Force Harrier and the Harrier GR7/GR9 strike aircraft in 2010, preparing for front-line operations.[190]

Royal Marines

The Royal Marines are an amphibious, specialised light infantry force of commandos, capable of deploying at short notice in support of Her Majesty's Government's military and diplomatic objectives overseas.[191] The Royal Marines are organised into a highly mobile light infantry brigade (3 Commando Brigade) and 7 commando units[192] including 1 Assault Group Royal Marines, 43 Commando Fleet Protection Group Royal Marines and a company strength commitment to the Special Forces Support Group. The Corps operates in all environments and climates, though particular expertise and training is spent on amphibious warfare, Arctic warfare, mountain warfare, expeditionary warfare and commitment to the UK's Rapid Reaction Force. The Royal Marines are also the primary source of personnel for the Special Boat Service (SBS), the Royal Navy's contribution to the United Kingdom Special Forces.[193]

The Royal Marines have seen action in a number of wars, often fighting beside the British Army; including in the Seven Years' War, the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War, World War I and World War II. In recent times, the Corps has been deployed in expeditionary warfare roles, such as the Falklands War, the Gulf War, the Bosnian War, the Kosovo War, the Sierra Leone Civil War, the Iraq War and the War in Afghanistan. The Royal Marines have international ties with allied marine forces, particularly the United States Marine Corps[194] and the Netherlands Marine Corps/Korps Mariniers.

Naval bases

The Royal Navy currently uses three major naval port bases in the UK, each housing its own flotilla of ships and boats ready for service along, two naval air stations and a support facility base in Bahrain:

Bases in the United Kingdom

- HMNB Devonport (HMS Drake) – This is currently the largest operational naval base in Western Europe. Devonport's flotilla consists of the RN's two amphibious assault vessels (HM Ships Albion and Bulwark), and half the fleet of Type 23 frigates. Also, Devonport homes some of the RN's Submarines service, including the fleet of Trafalgar-class submarines.[196]

- HMNB Portsmouth (HMS Nelson) – This is home to the future Queen Elizabeth Class supercarriers. Portsmouth is also the home to the Type 45 Daring Class Destroyer and a moderate fleet of Type 23 frigates as well as Fishery Protection Squadrons.[197]

- HMNB Clyde (HMS Neptune) – This is situated in Central Scotland along the River Clyde. Faslane is known as the home of the UK's nuclear deterrent, as it maintains the fleet of Vanguard-class ballistic missile (SSBN) submarines, as well as the fleet of Astute-class fleet (SSN) submarines. By 2020, Faslane will become the home to all Royal Navy submarines, and thus the RN Submarine Service. As a result, 43 Commando (Fleet Protection Group) are stationed in Faslane alongside to guard the base as well as The Royal Naval Armaments Depot at Coulport. Moreover, Faslane is also home to Faslane Patrol Boat Squadron (FPBS) who operates a fleet of Archer class patrol vessels.[198][199]

- RNAS Yeovilton (HMS Heron) – Yeovilton is home to Commando Helicopter Force and Wildcat Maritime Force.[200]

.jpg)

- RNAS Culdrose (HMS Seahawk) – This is home to Mk2 Merlins, primarily conducting Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) and Early Airborne Warning (EAW). Culdrose is also currently the largest helicopter base in Europe[201]

_(cn_50125-RN30)_Royal_Navy._(10475633143).jpg)

Bases abroad

- Mina Salman Support Facility (HMS Jufair) - HMS Jufair is the home port for vessels deployed on Operation Kipion[202] and acts as the hub of the Royal Navy's operations in the Gulf, Red Sea and Indian Ocean. Its fleet currently includes 9th Mine Countermeasures Squadron,[203] RFA Cardigan Bay and HMS Montrose.[204]

The current role of the Royal Navy is to protect British interests at home and abroad, executing the foreign and defence policies of Her Majesty's Government through the exercise of military effect, diplomatic activities and other activities in support of these objectives. The Royal Navy is also a key element of the British contribution to NATO, with a number of assets allocated to NATO tasks at any time.[205] These objectives are delivered via a number of core capabilities:[206]

- Maintenance of the UK Nuclear Deterrent through a policy of Continuous at Sea Deterrence

- Provision of two medium-scale maritime task groups with the Fleet Air Arm

- Delivery of the UK Commando force

- Contribution of assets to the Joint Helicopter Command

- Maintenance of standing patrol commitments

- Provision of mine counter measures capability to United Kingdom and allied commitments

- Provision of hydrographic and meteorological services deployable worldwide

- Protection of Britain and EU's Exclusive Economic Zone

Current deployments

The Royal Navy is currently deployed in different areas of the world, including some standing Royal Navy deployments. These include several home tasks as well as overseas deployments. The Navy is deployed in the Mediterranean as part of standing NATO deployments including mine countermeasures and NATO Maritime Group 2. In both the North and South Atlantic, RN vessels are patrolling. There is always a Falkland Islands patrol vessel on deployment, currently HMS Forth.[207]

The Royal Navy operates a Response Force Task Group (a product of the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review), which is poised to respond globally to short-notice tasking across a range of defence activities, such as non-combatant evacuation operations, disaster relief, humanitarian aid or amphibious operations. In 2011, the first deployment of the task group occurred under the name 'COUGAR 11' which saw them transit through the Mediterranean where they took part in multinational amphibious exercises before moving further east through the Suez Canal for further exercises in the Indian Ocean.[208][209]

In the Persian Gulf, the RN sustains commitments in support of both national and coalition efforts to stabilise the region. The Armilla Patrol, which started in 1980, is the navy's primary commitment to the Gulf region. The Royal Navy also contributes to the combined maritime forces in the Gulf in support of coalition operations.[210] The UK Maritime Component Commander, overseer of all of Her Majesty's warships in the Persian Gulf and surrounding waters, is also deputy commander of the Combined Maritime Forces.[211] The Royal Navy has been responsible for training the fledgeling Iraqi Navy and securing Iraq's oil terminals following the cessation of hostilities in the country. The Iraqi Training and Advisory Mission (Navy) (Umm Qasr), headed by a Royal Navy captain, has been responsible for the former duty whilst Commander Task Force Iraqi Maritime, a Royal Navy commodore, has been responsible for the latter.[212][213]

The Royal Navy contributes to standing NATO formations and maintains forces as part of the NATO Response Force. The RN also has a long-standing commitment to supporting the Five Powers Defence Arrangements countries and occasionally deploys to the Far East as a result.[214] This deployment typically consists of a frigate and a survey vessel, operating separately. Operation Atalanta, the European Union's anti-piracy operation in the Indian Ocean, is permanently commanded by a senior Royal Navy or Royal Marines officer at Northwood Headquarters and the navy contributes ships to the operation.[215]

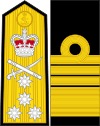

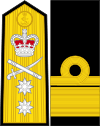

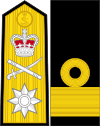

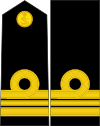

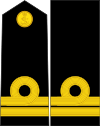

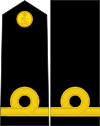

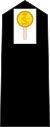

Command, control and organisation

The titular head of the Royal Navy is the Lord High Admiral, a position which has been held by the Duke of Edinburgh since 2011. The position had been held by Queen Elizabeth II from 1964 to 2011;[216] the Sovereign is the Commander-in-chief of the British Armed Forces.[217] The professional head of the Naval Service is the First Sea Lord, an admiral and member of the Defence Council of the United Kingdom. The Defence Council delegates management of the Naval Service to the Admiralty Board, chaired by the Secretary of State for Defence, which directs the Navy Board, a sub-committee of the Admiralty Board comprising only naval officers and Ministry of Defence (MOD) civil servants. These are all based in MOD Main Building in London, where the First Sea Lord, also known as the Chief of the Naval Staff, is supported by the Naval Staff Department.[218]

Organisation

The Fleet Commander has responsibility for the provision of ships, submarines and aircraft ready for any operations that the Government requires. Fleet Commander exercises his authority through the Navy Command Headquarters, based at HMS Excellent in Portsmouth. An operational headquarters, the Northwood Headquarters, at Northwood, London, is co-located with the Permanent Joint Headquarters of the United Kingdom's armed forces, and a NATO Regional Command, Allied Maritime Command.[219]