Taba language

| Taba | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Indonesia |

| Region | North Maluku province |

Native speakers | (20,000+ cited 1983)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

mky |

| Glottolog |

east2440[2] |

Taba (also known as East Makian or Makian Dalam) is a Malayo-Polynesian language of the South Halmahera – West New Guinea group. It is spoken mostly on the islands of Makian, Kayoa and southern Halmahera in North Maluku province of Indonesia by about 20,000 people.[3]

Dialects

There are minor differences in dialect between all of the villages on Makian island in which Taba is spoken. Most differences affect only a few words. One of the most widespread reflexes is the use of /o/ in Waikyon and Waigitang, where in other villages /a/ is retained from Proto-South Halmaheran.[4]

Geographic Distribution

As of 2005, Ethnologue lists Taba as having a speaking population of approximately 20,000, however, it has been argued by linguists that this number could in reality be anywhere between 20,000 and 50,000.[5] The language is predominantly spoken in Eastern Makian Island, although it is also found on Southern Mori Island, Kayoa islands, Bacan and Obi island and along the west coast of south Halmahera. There has also been continued migration of speakers to North Maluku due to frequent volcanic eruptions on Makian island.[6] The island itself is home to two languages: Taba, which is spoken on the eastern side of the island, and a Papuan language spoken on the western side, known alternatively as West Makian or Makian Luar (outer Makian); in Taba, this language is known as Taba Lik ("Outer Taba"), while its native speakers know it as Moi.

Speech Levels

Taba is divided into three different levels of speech: alus, biasa and kasar.

Alus, or ‘refined’ Taba is used in situations in which the speaker is addressing someone older or of greater status than the speaker themselves.

Biasa, or ‘ordinary’ Taba, is used in most general situations.

The Kasar, or ‘coarse’ form of Taba is used only rarely and generally in anger.

Phonology

Taba has fifteen indigenous consonant phonemes, and four loan phonemes: /ʔ dʒ tʃ f/. These are shown below:

| Bilabial | Apico-alveolar | Lamino-palatal | Dorso-velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | b p | d t | ɡ k | (ʔ) | |

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Affricate | (dʒ tʃ) | ||||

| Fricative | (f) | s | |||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Lateral | l | ||||

| Approximant | w | j | h |

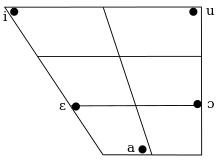

Taba has five vowels, illustrated on the table below. The front and central vowels are unrounded; the back vowels are rounded.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open | a aː |

Grammar

Word Order

Taba is, predominantly, a head-marking language which adheres to a basic AVO word order. However, there is a reasonable degree of flexibility.[9]

(1) yak k=ha-lekat pakakas ne 1SG 1SG=CAUS-broken tool PROX "I broke this tool."

Taba has both prepositions and postpositions.

Pronouns

| Person | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| 1INC | tit | |

| 1EXCL | yak | am |

| 2 | au | meu |

| 3 | i | si |

In Taba, pronouns constitute an independent, closed set. Syntactically, Taba pronouns can be used in any context where a full noun phrase is applicable. However, independent pronouns are only used in reference to animate entities, unless pronominal reference to inanimate Patients is required in reflexive clauses.[11]

As mentioned, independent pronouns are generally used for animate reference. However, there are two exceptions to this generalisation. In some circumstances an inanimate is considered a 'higher inanimate' which accords syntactic status similar to animates.[11] This is represented as in English where inanimates such as cars or ships, for example, can be ascribed a gender. This is illustrated below in a response to the question 'Why did the Taba Jaya (name of a boat) stop coming to Makian?':[11]

| (1) | Ttumo | i | te | ndara |

| t=tum-o | i | te | ndara | |

| 1pl.incl=follow-APPL | 3sg | NEG | too.much | |

| 'We didn't catch it enough.' |

The Taba Jaya, a boat significant enough to be given a name, is accorded pronoun status similar to animates. The other exception occurs in reflexive clauses where a pronominal copy of a reflexive Patient is required, as shown below:[11]

| (2) | Bonci | ncayak | i | tadia |

| bonci | n-say-ak | i | ta-dia | |

| peanut | 3sg-spread-APPL | 3sg | SIM-REM | |

| 'Peanut (leaves) spread out on itself like that.' | ||||

Non-human animates and inanimates are always grammatically singular, regardless of how many referents are involved. In Taba, pronouns and noun phrases are marked by Person and Number.

Person

Taba distinguishes three Persons in the pronominal and cross-referencing systems.[11] Person is marked on both pronouns and on cross-referencing proclitics attached to verb phrases.[12] The actor cross-referencing proclitics are outlined in the following table.[13] In the first Person plural, a clusivity distinction is made, 'inclusive' (including the adressee) and 'exclusive' (excluding the addressee), as is common to most Austronesian languages.[13]

| Cross-referencing Proclitics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1sg | k= | 1 pl.incl

1 pl.excl |

t=

a= |

| 2sg | m= | 2 pl | h= |

| 3sg | n= | 3 pl | l= |

The following are examples of simple Actor intransitive clauses showing each of the proclitic prefixes. This is an example of first Person singular (inclusive);[12]

| (3) | yak | kwom |

| yak | k=wom | |

| 1sg | 1sg=come | |

| 'I've come' | ||

second Person singular;[12]

| (4) | Au | mwom |

| au | m=wom | |

| 2sg | 2sg=come | |

| 'You've come. (you singular)' | ||

third Person singular;[12]

| (5) | I | nwom |

| i | n=wom | |

| 3sg | 3sg=come | |

| 'S/he's come.' | ||

first Person plural (inclusive);[12]

| (6) | Tit | twom |

| tit | t=wom | |

| 1pl.incl | 1pl.incl=come | |

| 'We've come. (You and I)' | ||

first Person plural (exclusive);[12]

| (7) | Am | awom |

| am | a=wom | |

| 1pl.excl | 1pl.excl=come | |

| 'We've come. (myself and one or more other people but not you)' | ||

second Person plural; and[12]

| (8) | Meu | hwom |

| meu | h=wom | |

| 2pl | 2pl=come | |

| 'You've come. (you plural)' | ||

third Person plural;[12]

| (9) | Si | lwom |

| si | l=wom | |

| 3pl | 3pl=come | |

| 'They've come.' | ||

The alternation between proclitic markers indicates Number, where in (3) k= denotes the arrival of a singular Actor, while in (7) a= indicates the arrival of first Person plural Actors, exclusionary of the addressee, and is replicated in the change of prefix in the additional examples.

Number

Number is marked on noun phrases and pronouns. Taba distinguishes grammatically between singular and plural categories, as shown in (3) to (9) above. Plural marking is obligatory for humans and is used for all noun phrases which refer to multiple individuals. Plurality is also used to indicate respect in the second and third Person when addressing or speaking of an individual who is older than the speaker.[4] The rules for marking Number on noun phrases are summarised in the table below:[4]

| Marking Number | ||

|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | |

| human | Used for one person when person is

same age or younger than speaker. |

Used for one person when person is older than speaker.

Used for more than one person in all contexts. |

| non-human animate | Used no matter how many referents | Not used |

| inanimate | Used no matter how many referents | Not used |

The enclitic =si marks Number in noun phrases. =si below (10), indicates that there is more than one child playing on the beach and, in (11), the enclitic indicates that the noun phase mama lo baba, translated as 'mother and father,' is plural.[4]

| (10) | Wangsi | lalawa | lawe | solo | li |

| wang=si | l=ha=lawa | la-we | solo | li | |

| child=PL | 3pl=CAUS-play | sea-ESS | beach | LOC | |

| 'The children are playing on the beach.' | |||||

| (11) | Nim | mama | li | babasi | laoblak |

| nim | mama | lo | baba=si | l-ha=obal-k | |

| 2SG.POSS | mother | and | father=PL | 3PL=CAUS-call-APPL | |

| 'Your mother and father are calling you.' | |||||

Plural Number is used as a marker of respect not only for second Person addressees, but for third Person referents as seen in (12).[4] In Taba, it has been observed that many adults use deictic shifts towards the perspective of addressee children regarding the use of plural markers. Example (13) is typical of an utterance of an older person than those they are referring to, indicative of respect that should be accorded to the referent by the addressee.[4]

| (12) | Ksung | Om | Nur | nidi | um | li |

| k=sung | Om | Nur | nidi | um | li | |

| 1sg=enter | Uncle | Nur | 3pl.POSS | house | LOC | |

| 'I went into Om Nur's house.' | ||||||

| (13) | Nim | babasi | e | lo | li | e? |

| nim | baba=si | e | lo | li | e | |

| 2sg.POSS | father=PL | FOC | where | LOC | FOC | |

| 'Where is your father?' | ||||||

Pronominal Affixes

All Taba verbs having Actor arguments carry affixes which cross-reference the Number and Person of the Actor, examples of proclitics are shown above. In Taba, there are valence-changing affixes which deal with patterns of cross-referencing with three distinct patterns. The dominant pattern is used with all verbs having an Actor argument. The other two patterns are confined to a small number of verbs: one for the possessive verb, the other for a few verbs of excretion. This is discussed further in Possession below.

Possession

Taba does not, as such, have possessive pronouns. Rather, the possessor noun and the possessed entity are linked by a possessive ligature. The Taba ligatures are shown below:

| Person | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| 1INC | nit | |

| 1EXCL | nik | am |

| 2 | nim | meu |

| 3 | ni | nidi/di |

Adnominal Possession

Adnominal possession involves the introduction of an inflected possessive particle between the possessor and the possessed entity; this inflected possessive, formally categorised as a ‘ligature’, is cross-referenced with the number and person of the possessor. This ligature indicates a possessive relationship between a modifier noun and its head-noun. In Taba, adnominal possession is distinguished by reverse genitive ordering, in which the possessor noun precedes the noun referring to the possessed entity.[14]

In many contexts the possessor will not be overtly referenced.

Example of reverse genitive ordering in Taba:

(12) ni mtu 3SG.POSS child "His/her child."

Obligatory Possessive Marking

In Taba, alienable and inalienable possession is not obligatorily marked by the use of different forms, though this is common in many related languages. However, there are a number of seemingly inalienable entities which cannot be referred to without referencing a possessor.[15]

For example:

(13) meja ni wwe table 3SG.POSS leg "The leg (of the table)."

Verbal Possession

Verbal possession in Taba is generally indicated through the attaching of the causative prefix ha- to the adnominal possessive forms. The possessor then becomes actor of the clause, and the possessed entity becomes the undergoer.[16] This method of forming a possessive verb is very unusual, typologically, and is found in almost no other languages.[17]

(14) kabin da yak k=ha-nik goat DIST 1SG 1SG=CAUS-1SG.POSS "That goat, I own it."

Name Taboo (Aroah)

As is common with many Melanesian people, Taba speakers practice ritual name taboo. As such, when a person dies in a Taba community, their name may not be used by any person with whom they had a close connection. This practice adheres to the Makianese belief that, if the names of the recently deceased are uttered, their spirits may be drastically disturbed. The deceased may be referred to simply as ‘Deku’s mother’ or ‘Dula’s sister’. Others in the community with the same name as the deceased will be given maronga, or substitute names.[18]

Notes

- ↑ Taba at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "East Makian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Ethnologue: Makian, East

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bowden 2001, p. 190

- ↑ Ethnologue: Makian, East

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 5

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 26

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 28

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 1

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 188

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bowden 2001, p. 190

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bowden 2001, p. 187

- 1 2 Bowden (2001). p. 194. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 230

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 233

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 197

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 239

- ↑ Bowden 2001, p. 22

References

- Bowden, John (2001). Taba: a Description of a South Halmahera Language. Pacific Linguistics. Canberra: Australian National University press.