Word order

| Linguistic typology |

|---|

| Morphological |

| Morphosyntactic |

| Word order |

| Lexicon |

In linguistics, word order typology is the study of the order of the syntactic constituents of a language, and how different languages can employ different orders. Correlations between orders found in different syntactic sub-domains are also of interest. The primary word orders that are of interest are the constituent order of a clause – the relative order of subject, object, and verb; the order of modifiers (adjectives, numerals, demonstratives, possessives, and adjuncts) in a noun phrase; and the order of adverbials.

Some languages use relatively restrictive word order, often relying on the order of constituents to convey important grammatical information. Others—often those that convey grammatical information through inflection—allow more flexibility, which can be used to encode pragmatic information such as topicalisation or focus. Most languages, however, have a preferred word order,[1] and other word orders, if used, are considered "marked".[2]

Most nominative–accusative languages—which have a major word class of nouns and clauses that include subject and object—define constituent word order in terms of the finite verb (V) and its arguments, the subject (S), and object (O).[3][4][5][6]

There are six theoretically possible basic word orders for the transitive sentence. The overwhelming majority of the world's languages are either subject–verb–object (SVO) or subject–object–verb (SOV), with a much smaller but still significant portion using verb–subject–object (VSO) word order. The remaining three arrangements are exceptionally rare, with verb–object–subject (VOS) being slightly more common than object–subject–verb (OSV), and object–verb–subject (OVS) being significantly more rare than the two preceding orders.[7]

Constituent word orders

| Word order | English equivalent | Proportion of languages | Example languages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | "She him loves." | 45% | Proto-Indo-European, Sanskrit, Hindi, Ancient Greek, Latin, Japanese, Korean | |

| SVO | "She loves him." | 42% | Cantonese, English, French, Hausa, Italian, Malay, Mandarin, Russian, Spanish | |

| VSO | "Loves she him." | 9% | Biblical Hebrew, Arabic, Irish, Filipino, Tuareg-Berber, Welsh | |

| VOS | "Loves him she." | 3% | Malagasy, Baure, Proto-Austronesian | |

| OVS | "Him loves she." | 1% | Apalaí, Hixkaryana, tlhIngan Hol | |

| OSV | "Him she loves." | 0% | Warao | |

| S-V1-O-V2 | "She can him love." | German, Afrikaans | ||

()

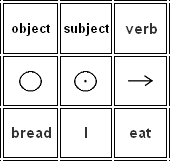

These are all possible word orders for the subject, verb, and object in the order of most common to rarest (the examples use "she" as the subject, "ate" as the verb, and "bread" as the object):

- SOV is the order used by the largest number of distinct languages; languages using it include Korean, Mongolian, Turkish, the Indo-Aryan languages and the Dravidian languages. Some, like Persian, Latin and Quechua, have SOV normal word order but conform less to the general tendencies of other such languages. A sentence glossing as "She bread ate" would be grammatically correct in these languages.

- SVO languages include English, the Romance languages, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbo-Croatian,[10] the Chinese languages and Swahili, among others. "She ate bread."

- VSO languages include Classical Arabic, Biblical Hebrew, the Insular Celtic languages, and Hawaiian. "Ate she bread" is grammatically correct in these languages.

- VOS languages include Fijian and Malagasy. "Ate bread she."

- OVS languages include Hixkaryana. "Bread ate she."

- OSV languages include Xavante and Warao. "Bread she ate."

Sometimes patterns are more complex: German, Dutch, Afrikaans and Frisian have SOV in subordinates, but V2 word order in main clauses, SVO word order being the most common. Using the guidelines above, the unmarked word order is then SVO.

Many synthetic languages such as Latin, Greek, Persian, Romanian, Assyrian, Russian, Turkish, Korean, Japanese, Finnish, and Basque have no strict word order; rather, the sentence structure is highly flexible and reflects the pragmatics of the utterance.

Topic-prominent languages organize sentences to emphasize their topic–comment structure. Nonetheless, there is often a preferred order; in Latin and Turkish, SOV is the most frequent outside of poetry, and in Finnish SVO is both the most frequent and obligatory when case marking fails to disambiguate argument roles. Just as languages may have different word orders in different contexts, so may they have both fixed and free word orders. For example, Russian has a relatively fixed SVO word order in transitive clauses, but a much freer SV / VS order in intransitive clauses. Cases like this can be addressed by encoding transitive and intransitive clauses separately, with the symbol 'S' being restricted to the argument of an intransitive clause, and 'A' for the actor/agent of a transitive clause. ('O' for object may be replaced with 'P' for 'patient' as well.) Thus, Russian is fixed AVO but flexible SV/VS. In such an approach, the description of word order extends more easily to languages that do not meet the criteria in the preceding section. For example, Mayan languages have been described with the rather uncommon VOS word order. However, they are ergative–absolutive languages, and the more specific word order is intransitive VS, transitive VOA, where S and O arguments both trigger the same type of agreement on the verb. Indeed, many languages that some thought had a VOS word order turn out to be ergative like Mayan.

Functions of constituent word order

A fixed or prototypical word order is one out of many ways to ease the processing of sentence semantics and reducing ambiguity. One method of making the speech stream less open to ambiguity (complete removal of ambiguity is probably impossible) is a fixed order of arguments and other sentence constituents. This works because speech is inherently linear. Another method is to label the constituents in some way, for example with case marking, agreement, or another marker. Fixed word order reduces expressiveness but added marking increases information load in the speech stream, and for these reasons strict word order seldom occurs together with strict morphological marking, one counter-example being Persian.[1]

Observing discourse patterns, it is found that previously given information (topic) tends to precede new information (comment). Furthermore, acting participants (especially humans) are more likely to be talked about (to be topic) than things simply undergoing actions (like oranges being eaten). If acting participants are often topical, and topic tends to be expressed early in the sentence, this entails that acting participants have a tendency to be expressed early in the sentence. This tendency can then grammaticalize to a privileged position in the sentence, the subject.

The mentioned functions of word order can be seen to affect the frequencies of the various word order patterns: The vast majority of languages have an order in which S precedes O and V. Whether V precedes O or O precedes V however, has been shown to be a very telling difference with wide consequences on phrasal word orders.[11]

Knowledge of word order on the other hand can be applied to identify the thematic relations of the NPs in a clause of an unfamiliar language. If we can identify the verb in a clause, and we know that the language is strict accusative SVO, then we know that Grob smock Blug probably means that Grob is the smocker and Blug the entity smocked. However, since very strict word order is rare in practice, such applications of word order studies are rarely effective.

History of constituent word order

A paper by Murray Gell-Mann and Merritt Ruhlen, building on work in comparative linguistics, asserts that the distribution of word order types in the world's languages was originally SOV. The paper compares a survey of 2135 languages with a "presumed phylogenetic tree" of languages, concluding that changes in word order tend to follow particular pathways, and the transmission of word order is to a great extent vertical (i.e. following the phylogenetic tree of ancestry) as opposed to horizontal (areal, i.e. by diffusion). According to this analysis, the most recent ancestor of currently known languages was spoken recently enough to trace the whole evolutionary path of word order in most cases.[12]

There is speculation on how the Celtic languages developed VSO word order. An Afro-Asiatic substratum has been hypothesized, but current scholarship considers this claim untenable, not least because Afro-Asiatic and Celtic were not in contact in the relevant period.[13][14]

Phrase word orders and branching

The order of constituents in a phrase can vary as much as the order of constituents in a clause. Normally, the noun phrase and the adpositional phrase are investigated. Within the noun phrase, one investigates whether the following modifiers occur before or after the head noun.

- adjective (red house vs house red)

- determiner (this house vs house this)

- numeral (two houses vs houses two)

- possessor (my house vs house my)

- relative clause (the by me built house vs the house built by me)

Within the adpositional clause, one investigates whether the languages makes use of prepositions (in London), postpositions (London in), or both (normally with different adpositions at both sides).

There are several common correlations between sentence-level word order and phrase-level constituent order. For example, SOV languages generally put modifiers before heads and use postpositions. VSO languages tend to place modifiers after their heads, and use prepositions. For SVO languages, either order is common.

For example, French (SVO) uses prepositions (dans la voiture, à gauche), and places adjectives after (une voiture spacieuse). However, a small class of adjectives generally go before their heads (une grande voiture). On the other hand, in English (also SVO) adjectives almost always go before nouns (a big car), and adverbs can go either way, but initially is more common (greatly improved). (English has a very small number of adjectives that go after their heads, such as extraordinaire, which kept its position when borrowed from French.)

Pragmatic word order

Some languages have no fixed word order and often use a significant amount of morphological marking to disambiguate the roles of the arguments. However, some languages use a fixed word order even if they provide a degree of marking that would support free word order. Also, some languages with free word order, such as some varieties of Datooga, combine free word order with a lack of morphological distinction between arguments.

Typologically, highly-animate actors are more likely topical than low-animate undergoers, a trend that would come through even in languages with free word order languages. That a statistical bias for SO order (or OS in the case of ergative systems, but ergative systems do not usually extend to the highest levels of animacy and usually give way to some form of nominative system, at least in the pronominal system).[15]

Most languages with a high degree of morphological marking have rather flexible word orders, such as Turkish, Latin, Portuguese, Ancient and Modern Greek, Romanian, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Serbo-Croatian, Russian (in intransitive clauses), and Finnish. In some of those languages, a canonical order can still be identified, but that is not possible in others. When the word order is free, different choices of word order can be used to help identify the theme and the rheme.

Hungarian

The word order in Hungarian sentences is changed according to the speaker’s communicative intentions. Hungarian word order is not free in the sense that it must reflect the information structure of the sentence, distinguishing the emphatic part that carries new information from the rest of the sentence that carries little or no new information.

The position of focus in a Hungarian sentence is immediately before the verb, that is, nothing can separate the emphatic part of the sentence from the verb.

For "Kate ate a piece of cake", the possibilities are:

- "Kati megevett egy szelet tortát." (same word order as English) ["Kate ate a piece of cake."]

- "Egy szelet tortát Kati evett meg." (emphasis on agent [Kate]) ["A piece of cake Kate ate."] (One of the pieces of cake was eaten by Kate.)

- "Kati evett meg egy szelet tortát." (also emphasis on agent [Kate]) ["Kate ate a piece of cake."] (Kate was the one eating one piece of cake.)

- "Kati egy szelet tortát evett meg." (emphasis on object [cake]) ["Kate a piece of cake ate."] (Kate ate a piece of cake – cf. not a piece of bread.)

- "Egy szelet tortát evett meg Kati." (emphasis on number [a piece, i.e. only one piece]) ["A piece of cake ate Kate."] (Only one piece of cake was eaten by Kate.)

- "Megevett egy szelet tortát Kati." (emphasis on completeness of action) ["Ate a piece of cake Kate."] (A piece of cake had been finished by Kate.)

- "Megevett Kati egy szelet tortát." (emphasis on completeness of action) ["Ate Kate a piece of cake."] (Kate finished with a piece of cake.)

The only freedom in Hungarian word order is that the order of parts outside the focus position and the verb may be freely changed without any change to the communicative focus of the sentence, as seen in sentences 2 and 3 or sentences 6 and 7 above. These pairs of sentences have the same information structure and communicative intention, because the part immediately preceding the verb is left unchanged.

Note that the emphasis can be on the action (verb) itself, as seen in sentences 1, 6 and 7 or on parts other than the action (verb), as seen in sentences 2, 3, 4 and 5. If the emphasis is not on the verb, and the verb has a co-verb (in the above example 'meg'), then the co-verb is separated from the verb, and always follows the verb. Also note that the enclitic -t marks the direct object: 'torta' (cake) + '-t' -> 'tortát'.

Portuguese

In Portuguese, clitic pronouns and commas allow many different orders:

- Eu vou entregar para você amanhã. ["I will deliver to you tomorrow."] (same word order as English)

- Entregarei para você amanhã. ["{I} will deliver to you tomorrow."]

- Eu lhe entregarei amanhã. ["I to you will deliver tomorrow."]

- Entregar-lhe-ei amanhã. ["Deliver to you {I} will tomorrow."] (mesoclisis)

- A si, eu entregarei amanhã. ["To you I will deliver tomorrow."]

- A si, entregarei amanhã. ["To you deliver {I} will tomorrow."]

- Amanhã, entregarei para você. ["Tomorrow {I} will deliver to you"]

- Poderia entregar, eu, a você amanhã? ["Could deliver I to you tomorrow?]

Braces ({ }) were used above to indicate omitted subject pronouns, which may be left implicit in Portuguese. Thanks to conjugation, the grammatical person is recovered.

Latin

In Latin, the endings of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and pronouns allow for extremely flexible order in most situations. Latin lacks articles.

The Subject, Verb, and Object can come in any order in a Latin sentence, although most often (especially in subordinate clauses) the verb comes last.[16] Pragmatic factors, such as topic and focus, play a large part in determining the order. Thus the following sentences each answer a different question:[17]

- Romulus Romam condidit. "Romulus founded Rome" (What did Romulus do?)

- Hanc urbem condidit Romulus. "Romulus founded this city" (Who founded this city?)

- Condidit Romam Romulus. "Romulus founded Rome" (What happened?)

Latin prose often follows the word order "Subject, Direct Object, Indirect Object, Adverb, Verb",[18] but this is more of a guideline than a rule. Adjectives in most cases go before the noun they modify,[19] but some categories, such as those that determine or specify (e.g. Via Appia "Appian Way"), usually follow the noun. In Classical Latin poetry, lyricists followed word order very loosely to achieve a desired scansion.

Albanian

Due to the presence of grammatical cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and in some cases or dialects vocative and locative) applied to nouns, pronouns and adjectives, the Albanian language permits a large number of positional combination of words. In spoken language a word order differing from the most common S-V-O helps the speaker putting emphasis on a word, thus changing partially the message delivered. Here is an example:

- "Marku më dha një dhuratë (mua)." ["Mark (me) gave a present to me.", neutral narrating sentence.]

- "Marku (mua) më dha një dhuratë." ["Mark to me (me) gave a present.", emphasis on the indirect object, probably to compare the result of the verb on different persons.]

- "Marku një dhuratë më dha (mua)." ["Mark a present (me) gave to me", meaning that Mark gave her only a present, and not something else or more presents.]

- "Marku një dhuratë (mua) më dha." ["Mark a present to me (me) gave", meaning that Mark gave a present only to her.]

- "Më dha Marku një dhuratë (mua)." ["Gave Mark to me a present.", neutral sentence, but puts less emphasis on the subject.]

- "Më dha një dhuratë Marku (mua)." ["Gave a present to me Mark.", probably is the cause of an event being introduced later.]

- "Më dha (mua) Marku një dhurate." ["Gave to me Mark a present.", same as above.]

- "Më dha një dhuratë mua Marku" ["(Me) gave a present to me Mark.", puts emphasis on the fact that the receiver is her and not someone else.]

- "Një dhuratë më dha Marku (mua)" ["A present gave Mark to me.", meaning it was a present and not something else.]

- "Një dhuratë Marku më dha (mua)" ["A present Mark gave to me.", puts emphasis on the fact that she got the present and someone else got something different.]

- "Një dhuratë (mua) më dha Marku." ["A present to me gave Mark.", no particular emphasis, but can be used to list different actions from different subjects.]

- "Një dhuratë (mua) Marku më dha." ["A present to me Mark (me) gave", remembers that at least a present was given to her by Mark.]

- "Mua më dha Marku një dhuratë." ["To me (me) gave Mark a present.", is used when Mark gave something else to others.]

- "Mua një dhuratë më dha Marku." ["To me a present (me) gave Mark.", emphasis on "to me" and the fact that it was a present, only one present or it was something different from usual."]

- "Mua Marku një dhuratë më dha" ["To me Mark a present (me) gave.", Mark gave her only one present.]

- "Mua Marku më dha një dhuratë" ["To me Mark (me) gave a present." puts emphasis on Mark. Probably the others didn't give her present, they gave something else or the present wasn't expected at all.]

In the aforementioned examples, "(mua)" can be omitted causing a perceivable change in emphasis, the latter being of different intensity. "Më" is always followed by the verb. Thus, a sentence consisting of a subject, a verb and two objects (a direct and an indirect one), can be expressed in six different ways without "mua", and in twenty-four different ways with "mua", adding up to thirty possible combinations.

Indo-Aryan languages

The word order of many Indo-Aryan languages can change depending on what specific implications a speaker wishes to make. These are generally aided by the use of appropriate inflectional suffixes. Consider these examples from Bengali:

- আমি ওটা জানি না। ["I that don't know.", typical, neutral sentence]

- আমি জানি না ওটা। ["I don't know that.", general emphasis on what isn't known]

- ওটা আমি জানি না। ["That I don't know.", agitation about what isn't known]

- ওটা জানি না আমি। ["That don't know I.", general emphasis on the person who doesn't know]

- জানি না আমি ওটা। ["Don't know I that.", agitation about the person who doesn't know]

- *জানি না ওটা আমি। [*"Don't know that I.", unused]

Other issues

In many languages, changes in word order occur due to topicalization or in questions. However, most languages are generally assumed to have a basic word order, called the unmarked word order; other, marked word orders can then be used to emphasize a sentence element, to indicate modality (such as an interrogative modality), or for other purposes.

For example, English is SVO (subject-verb-object), as in "I don't know that", but OSV is also possible: "That I don't know." This process is called topic-fronting (or topicalization) and is common. In English, OSV is a marked word order because it emphasises the object, and is often accompanied by a change in intonation.

An example of OSV being used for emphasis:

- A: I can't see Alice. (SVO)

- B: What about Bill?

- A: Bill I can see. (OSV, rather than I can see Bill, SVO)

Non-standard word orders are also found in poetry in English, particularly archaic or romantic terms – as the wedding phrase "With this ring, I thee wed" (SOV) or "Thee I love" (OSV) – as well as in many other languages.

Translation

Differences in word order complicate translation and language education – in addition to changing the individual words, the order must also be changed. This can be simplified by first translating the individual words, then reordering the sentence, as in interlinear gloss, or by reordering the words prior to translation.

See also

- Anastrophe, change in word order

- Antisymmetry

- Information flow

Notes

References

- 1 2 Comrie, Bernard (1981). Language universals and linguistic typology: syntax and morphology (2nd ed). University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ↑ Sakel, Jeanette (2015). Study Skills for Linguistics. Routledge. p. 61.

- ↑ Hengeveld, Kees (1992). Non-verbal predication. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-013713-5.

- ↑ Sasse, H.J. (1993). "Das Nomen – eine universelle Kategorie?". Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung. 46: 3.

- ↑ Jan Rijkhoff (2007) "Word Classes" Language and Linguistics Compass 1 (6) , 709–726 doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00030.x

- ↑ Rijkhoff, Jan (2004), "The Noun Phrase", Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-926964-5

- ↑ Tomlin, Russel S. (1986). Basic word order: Functional principles. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-415-72357-4.

- ↑ Meyer, Charles F. (2010). Introducing English Linguistics International (Student ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Tomlin, Russell S. (1986). Basic Word Order: Functional Principles. London: Croom Helm. p. 22. ISBN 9780709924999. OCLC 13423631.

- ↑ Kordić, Snježana (2006) [1st pub. 1997]. Serbo-Croatian. Languages of the World/Materials ; 148. Munich & Newcastle: Lincom Europa. pp. 45–46. ISBN 3-89586-161-8. OCLC 37959860. OL 2863538W. Contents. Summary. [Grammar book].

- ↑ Dryer, Matthew S. 1992. 'The Greenbergian Word Order Correlations', Language 68: 81–138

- ↑ Gell-Mann, Murray; Ruhlen, Merritt (10 October 2011). "The origin and evolution of word order". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (42): 17290–17295. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113716108.

- ↑ Graham Isaac, "Celtic and Afro-Asiatic" in The Celtic Languages in Contact (2007)

- ↑ Kim McCone, The origins and development of the Insular Celtic verbal complex, Maynooth studies in Celtic linguistics 6, 2006, ISBN 0901519464. Department of Old Irish, National University of Ireland, 2006.

- ↑ Comrie, Bernard (1981). Language universals and linguistic typology: syntax and morphology (2nd ed). University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ↑ Scrivner, Olga B. (2015). A Probabilistic Approach in Historical Linguistics: Word Order Change in Infinitival Clauses: From Latin to Old French. Indiana University PhD Thesis, p. 32, quoting Linde (1923).

- ↑ Spevak, Olga (2010). Constituent Order in Classical Latin Prose, p. 1, quoting Weil (1844).

- ↑ Devine, Andrew M. & Laurence D. Stephens (2006), Latin Word Order, p. 79.

- ↑ Walker, Arthur T. (1918) "Some Facts of Latin Word Order". The Classical Journal, Vol. 13, No. 9, pp. 644–657.

Further reading

- A collection of papers on word order by a leading scholar, some downloadable

- Basic word order in English clearly illustrated with examples.

- Language Universals and Linguistic Typology: Syntax and Morphology – Bernard Comrie (1981) – this is the authoritative introduction to word order and related subjects.

- Order of Subject, Object, and Verb (PDF) A basic overview of word order variations across languages.

- Haugan, Jens Old Norse Word Order and Information Structure. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. 2001 ISBN 82-471-5060-3

- Song, Jae Jung (2012) Word order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87214-0 & ISBN 978-0-521-69312-7