South African English phonology

This article covers the phonological system of South African English (SAE). While there is some variation among speakers, SAE typically has a number of features in common with English as it is spoken in southern England (in places like London), such as non-rhoticity and the TRAP–BATH split.

The two main phonological features that mark South African English as distinct are the behaviour of the vowels in KIT and PALM. The KIT vowel tends to be "split" so that there is a clear allophonic variation between the near-front [ɪ] and central [ɪ̈] or [ə]. The PALM vowel is characteristically back in the General and Broad varieties of SAE. The tendency to monophthongise /aʊ/ and /aɪ/ to [ɑː] and [aː] respectively, are also typical features of General and Broad White South African English.

Features involving consonants include the tendency for /tj/ (as in tune) and /dj/ (as in dune) to be realised as [tʃ] and [dʒ], respectively (See Yod coalescence), and /h/ has a strong tendency to be voiced initially.

Vowels

| Dia- phoneme |

White (Cultivated)[1][2][3] |

White (General)[1][2][3] |

White (Broad)[1][2][3] |

Black (Acrolect)[4] |

Black (Mesolect)[4] |

Lexical set |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ɪ/ | ɪ | ɪ | i | ɪ > i | i | KIT |

| ɪ̈ | ɪ̈~ə | |||||

| /iː/ | iː | FLEECE | ||||

| (/i/) | iˑ | ɪ > i | HAPPY | |||

| /ʊ/ | ʊ~ɵ | ʊ | u | ʊ > u | FOOT | |

| /uː/ | u̟ː | ʉː~yː | ʉː | u | ʊ > u | GOOSE |

| /ɛ/ | ɛ~e | e~ɪ | ɛ~e~ɪ | ɛ | DRESS | |

| /ə/ | ɐ, ə | ə | ɐ, ə | ə | ä | COMMA |

| /ər/ | ɐ, ə | ə | ɐ, ə, ɚ | ə | ä | LETTER |

| /ɜːr/ | əː~ɐː | ø̈ː~ø̞̈ː | ɜ~ə > ɛ | ɛ | NURSE | |

| /ɔː/ /ɔːr/ |

ɔ̝ː | oː | ɔː | THOUGHT NORTH | ||

| /æ/ | æ̝ | æ̝ | æ̝~ɛ~ɛ̝ | ɛ~æ̝ | ɛ | TRAP |

| /ʌ/ | ɐ~ä | ʌ > ä | ä | STRUT | ||

| /ɑː/ /ɑːr/ |

äː | ɑː | ɒː~ɔː | äː | äː~ʌː | PALM BATH START |

| /ɒ/ | ɒ̈ | ɒ̈~ʌ̈ | ɒ̈ | ɔ | ɔ~ɒ | LOT |

| ɒ̈ / ɔ̝ː | ɒ̈~ʌ̈ / oː | ɒ̈ / oː | ɔ | ɔ~ɒ | CLOTH[5] | |

| /ɪər/ | ɪə | ɪə~ɪː | e | NEAR | ||

| /ʊər/ | ʊə | ʊə~oː | oː | o? | o | CURE |

| /ɛər/ | ɛə | ɛː | eː | ɛ | ɛ~e | SQUARE |

| /eɪ/ | eɪ | eɪ~ɛɪ~æɪ | ɛɪ~äɪ~ʌɪ | ɛɪ~eɪ > e | e~ɛɪ | FACE |

| /oʊ/ | ɛʊ~œʊ | œʉ~œɨ̞~œː | ʌʊ | o~ɔ > əʊ | ɔ > ɔʊ | GOAT |

| /ɔɪ/ | ɔɪ~ɒɪ | ɔɪ | CHOICE | |||

| /aɪ/ | äɪ | äɪ~aː | ɑɪ~äː | ʌɪ > ʌ | ʌɪ | PRICE |

| /aʊ/ | äʊ | äʊ~ɑː | æʊ~jæʊ | aʊ > ɔ | ɔʊ > o | MOUTH |

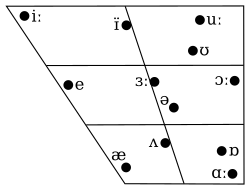

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | ɪ | iː | ʊ | uː | ||

| Mid | e | ə | ɜː | ɔː | ||

| Open | æ | ʌ | ɒ | ɑː | ||

/ɪ/ (the KIT vowel)

- In General and Broad, this vowel is allophonically split between a more front realisation ([ɪ] in General, [i] in Broad) and a more central realisation ([ɪ̈] in General, [ɪ̈] or [ə] in Broad). More front allophones are used in contact with velar and palatal consonants, whereas more central realisations are used in other environments, with an even more retracted [ɯ̈] being possible before the velarised allophone of /l/. The Cultivated variety lacks this split, and uses a lax front [ɪ] in every position.[6]

- Black mesolect realises it [i], whereas in the Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɪ] and [i].[7]

/iː/ (the FLEECE vowel)

- It is realised as [iː] in all White varieties.[8]

- In Black mesolect, the quality is also [i], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [i] and [ɪ].[7]

The HAPPY vowel

- The HAPPY vowel is not a phoneme. Depending on the variety, it can be considered to be phonemically either the FLEECE vowel (/iː/) or the KIT vowel (/ɪ/).

- It is a half-long [iˑ] in White varieties, which is their indicator. Syllables with this vowel may be either unstressed or secondarily stressed.[9]

- Black mesolect associates this vowel with the KIT vowel [ɪ], whereas in the Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɪ] and [i].[7]

/ʊ/ (the FOOT vowel)

- It is realised as a weakly rounded [ʊ̜] in White varieties. Broad speakers may pronounce it as more rounded [ʊ̹], but that is more common in Afrikaans English.[8]

- Black mesolect realises it as [u], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ʊ] and [u].[7]

/uː/ (the GOOSE vowel)

- It is usually central [ʉː] or somewhat fronter in White varieties, though in the Cultivated variety, it is closer to [uː]. Younger (particularly female) speakers of the General variety use an even more front vowel [yː].[8]

- Black mesolect realises it as [u], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ʊ] and [u].[7]

/e/ (the DRESS vowel)

- It is usually close-mid [e] in Cultivated and General varieties, sometimes even higher [e̝ ~ ɪ] in General and Broad. In Broad, it is usually open-mid [ɛ], with a potential [æ] allophone before the velarised allophone of /l/.[10]

- Black SAE (both mesolect and acrolect) realises it as [ɛ].[7]

/ə, ər/ (the COMMA and LETTER vowels)

- They are realised as [ə] in General and Broad, and vary between [ə] and [ɐ] in Cultivated and Broad varieties close to Afrikaans English.[9] In some older speakers of the Cultivated variety, they may be even fully open [ä].[11]

- Black mesolect realises them as [ɑ̈], whereas the Black acrolect realises them as [ə].[7]

/ɜː/ (the NURSE vowel)

- It is realised as a close-mid rounded vowel, either front [øː] or somewhat more central [ø̈ː] in General and Broad. In the Cultivated variety it is realised as [əː] (the same as in RP),[8] but sometimes it may be as open as [ɐː].[12]

- Black mesolect realises it as [ɛ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɜ], [ə] and [ɛ].[7]

/ɔː/ (the THOUGHT vowel)

- It is realised as a close-mid back rounded vowel [oː] in General and Broad varieties, whereas in the Cultivated variety, it is realised as mid [ɔ̝ː], the same as in RP.[13]

- Black SAE (both mesolect and acrolect) realises it as [ɔ].[7]

/æ/ (the TRAP vowel)

- In Cultivated and General varieties, it is realised as a sound between [æ] and [ɛ], i.e. [æ̝], but Broad speakers often raise it to [ɛ], which can merge with the Broad realisation of /e/.[8] However, [a] seems to be the new prestige value in younger Johannesburg (specifically in the northern Suburbs) speakers of General SAE.[14]

- Black mesolect realises it as [ɛ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɛ] and [æ].[7]

/ʌ/ (the STRUT vowel)

- It is realised as an open-to-mid central unrounded vowel [ä ~ ɐ] in White SAE.[8]

- Black mesolect realises it as [ɑ̈], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ʌ] and [ɑ̈].[7]

/ɑː/ (the PALM/BATH vowel)

- In the General variety, it is a fully back open unrounded vowel [ɑː]. In the Cultivated variety, it is somewhat more central [ɑ̟ː] whereas in Broad, the tendency is to realise a shortened, rounded and raised vowel [ɒ ~ ɔ].[8]

- Black mesolect realises it as [ɑ̈], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɑ̈] and [ʌ].[7]

/ɒ/ (the LOT vowel)

- It is realised as a back vowel, either a centralized open rounded [ɒ̈] or an open-mid rounded [ɔ]. Younger General speakers in Cape Town and Natal tend to use an unrounded centralized open-mid [ʌ̈].[8]

- Black mesolect realises it as [ɔ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɔ] and [ɒ].[7]

| Ending point | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | |

| Close | ɪə ʊə | ||

| Mid | eɪ ɔɪ | eə | əʊ |

| Open | aɪ | aʊ | |

/ɪə/ (the NEAR vowel)

- It is realised as [ɪə] in White varieties, but Broad speakers tend to monophthongize it to [ɪː], especially after /j/.[16]

- Black SAE (both mesolect and acrolect) realises it as [e].[7]

/ʊə/ (the CURE vowel)

- It is realised as [ʊə] in the Cultivated variety, whereas in Broad it is monophthongized to [oː]. The General variety varies between these two, with a growing tendency to use the monophthong [oː] (the same as the THOUGHT vowel or somewhat lower), especially when /j/ doesn't precede.[17]

- Black mesolect realises it as [o].[18]

/eə/ (the SQUARE vowel)

- It is realised as [ɛə] in the Cultivated variety, monophthongized to [ɛː] in Broad and monophthongized and raised to [eː] in General.[16]

- Black mesolect realises it as [ɛ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɛ] and [e].[7]

/eɪ/ (the FACE vowel)

- It is realised as [eɪ] in General and Cultivated, with opener variants [ɛɪ ~ æɪ] being possible in accents closer to Broad SAE. In Broad SAE, the first element is back [ʌɪ].[16]

- In Black mesolect, the quality varies between [ɛɪ], [eɪ] and [ɛ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [e] and [ɛɪ].[7]

/əʊ/ (the GOAT vowel)

- This vowel regularly has a rather front onset in Cultivated and General varieties. In Cultivated, it is realised as [ɛʊ ~ œʊ], with the former being more common. In General, the onset is always rounded, and the offset is central [œʉ ~ œɨ̞], with a tendency to monophthongize it to [œː]. The Broad realisation is back [ʌʊ].[16]

- In Black mesolect, the quality varies between [ɔ] and [ɔʊ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [o], [ɔ] and [əʊ].[7]

/ɔɪ/ (the CHOICE vowel)

- It is realised as [ɔɪ] in all White varieties. In the Cultivated variety, the first element may be lowered to [ɒ].[16]

- Black SAE (both mesolect and acrolect) realises it as [ɔɪ].[7]

/aɪ/ (the PRICE vowel)

- It is realised as a diphthong [aɪ] in Cultivated. In General and Broad, it is more often a monophthong [aː], with a diphthong with a retracted onset [ɑ̽ɪ] also possible in Broad.[16]

- Black mesolect realises it as [ʌɪ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ʌɪ] and [ʌ].[7]

/aʊ/ (the MOUTH vowel)

Consonants

Plosives

The plosive phonemes of South African English are /p, b, t, d, k, ɡ/.

- In Broad White South African English, voiceless plosives tend to be unaspirated in all positions, which serves as a marker of this subvariety.[9][19] This is usually thought to be an Afrikaans influence.[19]

- General and Cultivated varieties aspirate /p, t, k/ before a stressed syllable, unless they are followed by an /s/ within the same syllable.[9][19]

- /t, d/ are normally alveolar.[19] In the Broad variety, they tend to be dental [t̪, d̪].[9][19] This pronunciation also occurs in older speakers of the Jewish subvariety of Cultivated SAE.[19]

Fricatives and affricates

The fricative and affricate phonemes of South African English are /f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, x, h, tʃ, dʒ/.

- /x/ occurs only in words borrowed from Afrikaans and Khoisan, such as gogga /ˈxɒxə/ 'insect'. Many speakers realise /x/ as uvular [χ], a sound which is more common in Afrikaans.[9]

- /θ/ may be realised as [f] in Broad varieties (see Th-fronting), but it is more accurate to say that it is a feature of Afrikaans English.[9][19] This is especially common word-finally.[19]

- /v, ð, z, ʒ/ in word-final position tend to be voiceless. They contrast with /f, θ, s, ʃ/ by the presence or lack of pre-fortis clipping.[9]

- In Indian variety, the labiodental fricatives /f, v/ are realised without audible friction, i.e. as approximants [ʋ̥, ʋ].[20]

- In General and Cultivated varieties, intervocalic /h/ (as in ahead) may be voiced [ɦ].[21]

- There is not a full agreement about the voicing of /h/ in Broad varieties:

- Lass (2002) states that:

- Voiced [ɦ] is the normal realisation of /h/ in Broad varieties.[21]

- It is often deleted, e.g. in word-initial stressed syllables (as in house), but at least as often, it is pronounced even if it seems deleted. The vowel that follows the [ɦ] allophone in the word-initial syllable often carries a low or low rising tone, which, in rapid speech, can be the only trace of the deleted /h/. That creates potentially minimal tonal pairs like oh (neutral [əʊ˧] or high falling [əʊ˦˥˩]) vs. hoe (low [əʊ˨] or low rising [əʊ˩˨]).[21]

- Bowerman (2004) states that in Broad varieties close to Afrikaans English, /h/ is voiced [ɦ] before a stressed vowel.[9]

- Lass (2002) states that:

Sonorants

The sonorant phonemes of South African English are /m, (hw), w, n, l, r, j, ŋ/.

- General and Broad varieties have a wine–whine merger. but some speakers of Cultivated SAE (particularly the elderly) still distinguish /hw/ from /w/.[22][23]

- /n/ is normally alveolar, but it has an optional dental allophone [n̪] before dental consonants.[19][22]

- /l/ has two allophones:

- Clear (neutral or somewhat palatalised)[23] [l] in syllable-initial position;[22][23]

- Velarised [lˠ] (or uvularised [lʶ])[23] in syllable-final position.[22][23]

- One source states that the dark /l/ has a "hollow pharyngealised" quality [lˤ],[15] rather than velarised or uvularised.

- In Cultivated and General varieties, /r/ is an approximant, usually postalveolar or (less commonly)[19] retroflex.[19][22] In emphatic speech, Cultivated speakers may realise /r/ as a (often long) trill [r].[23] Older speakers of the Cultivated variety may realise intervocalic /r/ as a tap [ɾ], a feature which is becoming increasingly rare.[23]

- Broad SAE realises /r/ as a tap [ɾ], sometimes even as a trill [r] - a pronunciation which is at times stigmatised as a marker of this variety.[22][23] The trill [r] is more commonly considered a feature of the second language Afrikaans English variety.[22][23]

- Another possible realisation of /r/ is uvular trill [ʀ], which has been reported to occur in the Cape Flats dialect.[24]

- South African English is non-rhotic, except for some Broad varieties spoken in the Cape Province (typically in -er suffixes, as in writer). It appears that postvocalic /r/ is entering the speech of younger people under the influence of American English.[22][23]

- Linking /r/ (as in for a while) is used only by some speakers.[22]

- There is not a full agreement about intrusive /r/ (as in law and order) in South African English:

- Lass (2002) states that it is rare, and some speakers with linking /r/ never use the intrusive /r/.[21]

- Bowerman (2004) states that it is absent from this variety.[22]

- In contexts where many British and Australian accents use the intrusive /r/, speakers of South African English who do not use the intrusive /r/ create an intervocalic hiatus. Phonetically, it can be realised in three ways:[22]

- Vowel deletion: [ˈlɔː‿n‿ˈɔːdə];[22]

- Adding a semivowel corresponding to the preceding vowel: [ˈlɔː‿wən‿ˈɔːdə];[22]

- Inserting a glottal stop: [ˈlɔː ʔən‿ˈɔːdə]. This is typical of Broad varieties.[22]

- Before a high front vowel, /j/ is foritified to [ɣ] in Broad and some of the General varieties.[22]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Wells (1982).

- 1 2 3 Lass (2002).

- 1 2 3 Bowerman (2004).

- 1 2 van Rooy (2004).

- ↑ Lass (2002:116), "Certain words where the vowel is followed by a voiceless fricative may have either (long) THOUGHT or (short) LOT: this is quite variable, and different speakers may have quite different distributions. (Wells has a separate class, CLOTH, for such items.) In general, the more conservative the style or lect, the less likely the CLOTH words (e.g. off, soft, cloth, wrath, loss, Austria, Austin) are to have THOUGHT; though most varieties have it in off."

- ↑ Bowerman (2004), p. 936.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Van Rooy (2004), pp. 945, 947.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bowerman (2004), p. 937.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bowerman (2004), p. 939.

- ↑ Bowerman (2004), pp. 936–937.

- ↑ Lass (2002), p. 119.

- ↑ Wells (1982), p. 615.

- ↑ Bowerman (2004), pp. 937–938.

- ↑ Bekker (2008:83–84) "More recently, Bekker and Eley (2007) conducted an acoustic analysis of the monophthongs of GenSAE, using data elicited from two sets of subjects: young females from private schools in Johannesburg and young females from public schools in East London. Results suggest that a lowered TRAP vowel is a new prestige value, particularly for the Johannesburg area, and more specifically for one of the more wealthy areas of Johannesburg; the so-called ‘northern Suburbs’ (...)."

- 1 2 3 Collins & Mees (2013), p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bowerman (2004), p. 938.

- ↑ Bowerman (2004), pp. 938–939.

- ↑ Van Rooy (2004), p. 945.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lass (2002), p. 120.

- ↑ Mesthrie (2004), p. 960.

- 1 2 3 4 Lass (2002), p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Bowerman (2004), p. 940.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lass (2002), p. 121.

- ↑ Finn (2004), p. 976.

Bibliography

- Bekker, Ian (2008). The vowels of South African English (PDF) (Ph.D.). north-West University, Potchefstroom.

- Bowerman, Sean (2004), "White South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 931–942, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2013) [First published 2003], Practical Phonetics and Phonology: A Resource Book for Students (3rd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-50650-2

- Finn, Peter (2004), "Cape Flats English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 964–984, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Lass, Roger (2002), "South African English", in Mesthrie, Rajend, Language in South Africa, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521791052

- Mesthrie, Rajend (2004), "Indian South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 953–963, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- van Rooy, Bertus (2004), "Black South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 943–952, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Wade, Rodrik D. (1996). "Structural characteristics of Zulu English". An Investigation of the Putative Restandardisation of South African English in the Direction of a 'New' English, Black South African English (Thesis). Durban: University of Natal. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008.

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Volume 3: Beyond the British Isles (pp. i–xx, 467–674). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52128541-0.

Further reading

- Branford, William (1994). "9: English in South Africa". In Burchfield, Robert. The Cambridge History of the English Language. 5: English in Britain and Overseas: Origins and Development. Cambridge University Press. pp. 430–496. ISBN 0-521-26478-2.

- Da Silva, Arista B. (2008). South African English: a sociolinguistic investigation of an emerging variety (PDF) (Ph.D thesis). University of Johannesburg.

- De Klerk, Vivian, ed. (1996). Focus on South Africa. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-272-4873-7.

- Lanham, Len W. (1967). The pronunciation of South African English. Cape Town: Balkema. OCLC 457559.

- Prinsloo, Claude Pierre (2000). A comparative acoustic analysis of the long vowels and diphthongs of Afrikaans and South African English (PDF) (M.Eng thesis). Pretoria: University of Pretoria.