Norwegian phonology

The sound system of Norwegian resembles that of Swedish. There is considerable variation among the dialects, and all pronunciations are considered by official policy to be equally correct - there is no official spoken standard, although it can be said that Bokmål has an unofficial spoken standard, called Urban East Norwegian or Standard East Norwegian (Norwegian: Standard Østnorsk), loosely based on the speech of the literate classes of the Oslo area. This variant is the most common one taught to foreign students.[1]

Despite there being no official standard variety of Norwegian, Urban East Norwegian has traditionally been used in public venues such as theatre and TV, although today local dialects are used extensively in spoken and visual media.[2]

The background for this lack of agreement is that after the dissolution of Denmark–Norway in 1814, the upper classes would speak in what was perceived as the Danish language, which with the rise of Norwegian romantic nationalism gradually fell out of favour. In addition, Bergen, not Oslo, was the larger and more influential city in Norway until the 19th century. See the article on the Norwegian language conflict for further information.

Unless noted otherwise, this article describes the phonology of Urban East Norwegian.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʂ | ç | h |

| Approximant | ʋ | l | j | |||

| Flap | ɾ | ɽ | ||||

- /n, t, d/ are laminal [n̻, t̻, d̻], either alveolar [n, t, d] or denti-alveolar [n̪, t̪, d̪].[3]

- /p, t, k/ are aspirated fully voiceless [pʰ, tʰ, kʰ], whereas /b, d, ɡ/ are unaspirated, either fully voiceless [p˭, t˭, k˭] or partially voiced [b̥˭, d̥˭, ɡ̊˭]. After /s/ within the same syllable, only unaspirated voiceless stops occur.[3]

- /s/ is dentalized laminal alveolar [s̪] or (uncommonly) non-retracted apical alveolar [s̺].[4]

- /ʂ/ is pronounced with protruded lips [ʂʷ]. The degree of protrusion depends on the rounding of the following vowel.[5]

- /h/ is a (usually voiceless) fricative. The friction is normally glottal [h], but sometimes it is dorsal: palatal [ç] when near front vowels, velar [x] near back vowels. It can be voiced [ɦ ~ ʝ ~ ɣ] between two voiced sounds.[6]

- /ʋ, l, j, ɾ/ are partially voiced or fully voiceless [f, l̥, ç, ɾ̥] when they occur after /p, t, k, f/ (but not when /s/ precedes within the same syllable). The flap /ɾ/ is also partially voiced or fully voiceless when it occurs postvocalically before /p, k, f/.[7]

- The approximants /ʋ, j/ may be realized as fricatives [v, ʝ]:[8][9]

- /ʋ/ is sometimes a fricative, especially before a pause and in emphatic pronunciation.[8][9]

- There is not an agreement about the frequency of occurrence of the fricative allophone of /j/:

- Kristoffersen (2000) states that /j/ is sometimes a fricative.[8]

- Vanvik (1979) states that the fricative variant of /j/ occurs often, especially before and after close vowels and in energetic pronunciation.[9]

- /l/ is in process of changing from laminal denti-alveolar [l̪] to apical alveolar [l̺], which leads to neutralization with the retroflex allophone [ɭ]. Laminal realization is still possible before vowels, after front and close vowels and after consonants that are not coronal, and is obligatory after /n, t, d/. A velarized laminal [ɫ̪] occurs after mid back vowels /ɔ, ɔː/, open back vowels /ɑ, ɑː/, and sometimes also after the close back vowels /u, uː/.[10] However, Endresen (1990) states that at least in Oslo, the laminal variant is not velarized, and the difference is only between an apical and a laminal realization.[11]

- /ɾ/ is an voiced apical alveolar flap [ɾ̺]. It is occasionally trilled [r], e.g. in emphatic speech.[12]

- Retroflex allophones [ɳ, ʈ, ɖ] have been variously described as apical alveolar [n̺, t̺, d̺] and apical postalveolar [n̠, t̠, d̠].[3]

- /ɽ/ alternates with /ɾ/ in many words, but there is a small number of words in which only /ɽ/ occurs.[12]

- /ŋ, k, ɡ/ are velar, whereas /j/ is palatal.[3]

- /ç/ may be palatal [ç], but is often alveolo-palatal [ɕ] instead. It is unstable in many dialects, and younger speakers in Bergen, Stavanger and Oslo merge /ç/ with /ʂ/ into [ʂ].[13]

- Glottal stop [ʔ] may be inserted before word-initial vowels. In very emphatic speech, it can also be inserted word-medially in stressed syllables beginning with a vowel.[14]

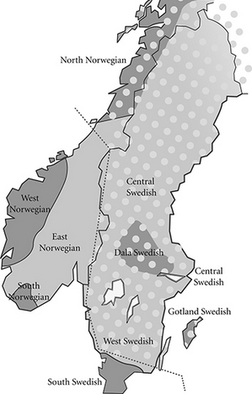

Most of the retroflex (and postalveolar) consonants are mutations of [ɾ]+any other alveolar/dental consonant; rn /ɾn/ > [ɳ], rt /ɾt/ > [ʈ], rl /ɾl/ > [ɭ], rs /ɾs/ > [ʂ], etc. /ɾd/ across word boundaries (sandhi), in loanwords and in a group of primarily literary words may be pronounced [ɾd], e.g., verden [ˈʋæɾdn̩], but it may also be pronounced [ɖ] in some dialects. Most of the dialects in Eastern, Central and Northern Norway use the retroflex consonants. Most Southern and Western dialects do not have these retroflex sounds, because in these areas a guttural realization of the /r/ phoneme is commonplace, and seems to be expanding. Depending on phonetic context voiceless ([χ]) or voiced uvular fricatives ([ʁ]) are used. (See map at right.) Other possible pronunciations include a uvular approximant [ʁ̞] or, more rarely, a uvular trill [ʀ]. There is, however, a small number of dialects that use both the uvular /r/ and the retroflex allophones.

The retroflex flap, [ɽ], colloquially known to Norwegians as tjukk l ('thick l'), is a Central Scandinavian innovation that exists in Eastern Norwegian (including Trøndersk), the southmost Northern dialects, and the most eastern Western Norwegian dialects. It is supposedly non-existent in most Western and Northern dialects. Today there is doubtlessly distinctive opposition between /ɽ/ and /l/ in the dialects that do have /ɽ/, e.g. gard /ɡɑːɽ/ 'farm' and gal /ɡɑːl/ 'crazy' in many Eastern Norwegian dialects. Although traditionally an Eastern Norwegian dialect phenomenon, it was considered vulgar, and for a long time it was avoided. Nowadays it is considered standard in the Eastern and Central Norwegian dialects,[15] but is still clearly avoided in high-prestige sociolects or standardized speech. This avoidance calls into question the status of /ɽ/ as a phoneme in certain sociolects.

According to Nina Grønnum, tjukk l in Trøndersk is actually a postalveolar lateral flap [ɺ̠].[16]

Vowels

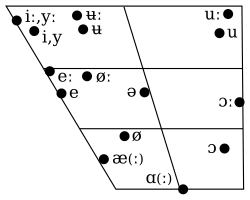

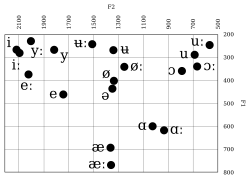

Monophthongs

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | y | yː | ʉ | ʉː | u | uː |

| Mid | e | eː | ø | øː | ɔ | ɔː | ||

| Open | æ | æː | ɑ | ɑː | ||||

- Unless preceding another vowel within the same word, all unstressed vowels are short.[18]

- /eː, øː/ are frequently realized as centering diphthongs [eə, øə]. /iː, yː, uː, ɔː/ can also be realized as [iə, yə, uə, ɔə], yet /ʉː, æː, ɑː/ are always monophthongal.[19][20] However, according to Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005), the diphthongal variants of /eː, øː, ɔː/ are opening [eːɛ̯, øːœ̯, ɔːɑ̯], not centering.[21]

The following sections describe each monophthong in detail.

Symbols (IPA)

- The vowels /iː, yː, ʉː, eː, ɔ, æ, æː/ as well as the [ə] allophone of /e/ are invariably transcribed with ⟨iː, yː, ʉː, eː, ɔ, æ, æː⟩ and ⟨ə⟩.[22]

- The short close vowels /i, y, u/ are more often transcribed with ⟨i, y, u⟩ than with ⟨ɪ, ʏ, ʊ⟩.[23] Some sources mix these sets, e.g. Krech et al. (2009) uses ⟨i, ʏ, u⟩. Some older sources[24] transcribe /u/ with an obsolete symbol ⟨ɷ⟩. This article uses ⟨i, y, u⟩.

- The short close central rounded vowel /ʉ/ is most often transcribed with ⟨ʉ⟩,[25] but ⟨ʉ̞⟩[26] and ⟨ᵿ⟩[27] also occur (but note that ⟨ᵿ⟩ is not a part of the official IPA). This article uses ⟨ʉ⟩.

- The long close back rounded vowel /uː/ is most often transcribed with ⟨uː⟩.[28] Some older sources[24] transcribe it with an obsolete symbol ⟨ɷː⟩. This article uses the former symbol.

- The short mid front vowels /e, ø/ are variably transcribed with ⟨e, ø⟩[29] and ⟨ɛ, œ⟩.[30] Some sources mix these sets, e.g. Haugen (1974) uses ⟨ɛ, ø⟩ whereas Krech et al. (2009) uses ⟨e, œ⟩. This article uses ⟨e, ø⟩.

- The long mid vowels /øː, ɔː/ are most often transcribed with ⟨øː, ɔː⟩,[31] but Kristoffersen (2000) uses both ⟨øː⟩ and ⟨ɵː⟩ for the former and ⟨oː⟩ for the latter. This article uses ⟨øː, ɔː⟩.

- The open back unrounded vowels /ɑ, ɑː/ are most often transcribed with ⟨ɑ, ɑː⟩,[32] but Vanvik (1979) transcribes them with ⟨a, aː⟩. This article uses the former set.

Symbols (non-IPA)

Some writings[33] use a set of symbols that is much more based on the Norwegian alphabet, so that:

- The ordinary colon ⟨:⟩ is used in place of the special triangular IPA colon ⟨ː⟩.[34][35][36][37] Sporadically, this also appears in writings[38] that otherwise use the IPA transcription.

- The stressed syllables may be indicated by underlining the stressed vowel.[37]

- The short vowels are written with the same symbols as the long vowels (save for the colon), so that e.g. /e, eː/ are transcribed with ⟨e, e:⟩.[34][35][36][37]

- The close rounded vowels /ʉ, ʉː, u, uː/ are transcribed with ⟨u, u:, o, o:⟩.[34][35][36][37]

- The back vowels /ɔ, ɔː, ɑ, ɑː/ can be transcribed either with ⟨å, å:, a, a:⟩,[34][35][37] or with the IPA symbols ⟨ɔ, ɔ:, ɑ, ɑ:⟩ (save for the special IPA colon).[36]

This type of transcription may even appear in works[39] that use the IPA transcription for other languages.

Phonetic realization of the close vowels

- /i/ has been variously described as near-close front unrounded [i̞][40][41] and close front unrounded [i].[42] It is pronounced with spread lips, although somewhat less spread than in /iː/.[43]

- /iː/ is close front unrounded [iː].[40][42][44] It is pronounced with spread lips.[44]

- /y/ is near-close front rounded [y˕].[45][46][47] Its rounding is protruded [iʷ].[47][48][49]

- /yː/ has been variously described as close front rounded [yː][50] and near-close front rounded [y˕ː].[45][51] Its rounding is protruded [iʷː].[48][49][52]

- /ʉ/ has been variously described as near-close front rounded [ʉ̞˖],[50] near-close central rounded [ʉ̞][53] and close central rounded [ʉ].[54] Its rounding has been variously described as compressed [ɨᵝ][48][55] and protruded [ɨʷ].[55][56]

- /ʉː/ has been variously described as close front rounded [ʉ̟ː][57] and close central rounded [ʉː].[54][58] Its rounding has been variously described as compressed [ɨᵝː][48][55] and protruded [ɨʷː].[55][59]

- /u/ has been variously described as near-close back rounded [u̞][57][60] and close back rounded [u].[61] Its rounding has been most often described as compressed [ɯᵝ],[48][62] but at least one source describes it as protruded [ɯʷ].[60]

- /uː/ is close back rounded [uː].[61][63][64] Its rounding has been most often described as compressed [ɯᵝː],[48][62] but at least one source describes it as protruded [ɯʷː].[65]

Phonetic realization of the mid vowels

- /e/ is mid front unrounded [e̞].[42][66][67] It is pronounced with spread lips, although somewhat less spread than in /eː/.[68]

- /eː/ has been variously described as close-mid front unrounded [eː][40][71] and mid front unrounded [e̞ː].[42] It is pronounced with spread lips.[72]

- /ø/ has been variously described as open-mid front rounded [œ][46][73] and ranging from open-mid front rounded [œ] to mid front rounded [ø̞].[74] Its rounding is protruded [eʷ].[48][73]

- According to Kristoffersen (2000), /ø/ is actually pronounced the same as an unstressed allophone of /e/, i.e. mid central unrounded [ə]. This hardly leads to a phonemic neutralization with /e/ in unstressed syllables as /ø/ is rather rare in those positions.[75]

- /øː/ has been variously described as close-mid central rounded [ɵː],[76] close-mid front rounded [øː],[46] mid front rounded [ø̞ː][77] and ranging from mid front rounded [ø̞ː] to open-mid front rounded [œː].[74] Its rounding is protruded [eʷː].[48][78]

- /ɔ/ has been variously described as open-mid near-back rounded [ɔ̟],[79] open-mid back rounded [ɔ][80] and near-open back rounded [ɔ̞].[63] Its rounding is protruded [ʌʷ].[48][81]

- /ɔː/ is mid back rounded [ɔ̝ː].[63][79][82] Its rounding is protruded [ʌ̝ʷː].[48][83]

Phonetic realization of the open vowels

- /æ, æː/ are near-open front unrounded [æ, æː].[66][84][85] Kristoffersen (2000) reports somewhat more central realizations, more or less like [ä, äː].[86] They are pronounced with spread lips.[87]

- The phonemic status of [æ] and [æː] in Urban East Norwegian is unclear since these pattern as allophones of, respectively, /e/ and /eː/ before the flaps /ɾ/ and /ɽ/. However, there also are words in which /eː/ is realized as [eː] despite the following flap, such as Per [peːɾ] 'Peter'. [æ] also occurs in the diphthongs /æi/ and /æʉ/, which can be analyzed as /ej/ and /ew/.[88] There also are minimal pairs like hacke [ˈhækə] ('to hack', from English) vs. hekke [ˈhekə] ('to nest').

- /ɑ, ɑː/ are open back unrounded [ɑ, ɑː].[89][90][91] They are pronounced with neutral lips.[92]

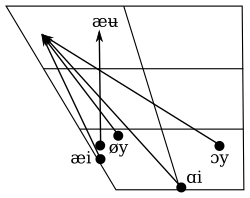

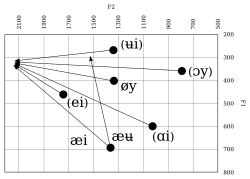

Diphthongs

Norwegian diphthong phonemes are /øy, æi, æʉ/.[18] Marginal diphthongs are /ʉi, ei, ɔy, ɑi/.[18] Their starting and ending points have very similar quality to the short vowels transcribed the same way.[95][96][97]

- /ʉi/ appears only in the word hui.[18]

- /ei, ɔy, ɑi/ appear only in loanwords.[18]

- /ei/ is used only by some younger speakers, who contrast it with /æi/. Speakers who do not have /ei/ in their diphthong inventory replace it with /æi/.[18]

- The offset of /æʉ/ is often realized as a labiodental approximant, which turns this diphthong into a sequence [æʋ].[18]

Kristoffersen (2000) analyses Norwegian diphthongs as sequences of a short vowel and a semivowel /j/ (which is allophonically rounded after rounded vowels) or /w/ (which corresponds to central /ʉ/, not back /u/).[98] On the other hand, both Vanvik (1979) and Strandskogen (1979) analyze them as diphthongs.

Accent

Norwegian is a pitch accent language with two distinct pitch patterns. They are used to differentiate polysyllabic words with otherwise identical pronunciation. Although difference in spelling occasionally allows the words to be distinguished in the written language (such as bønner/bønder), in most cases the minimal pairs are written alike. For example, in most Norwegian dialects, the word uttale ('pronounce') is pronounced using tone 1 ([ˈʉːttɑːlə]), while uttale ('pronunciation') uses tone 2 ([²ʉːttɑːlə]).

There are significant variations in the realization of the pitch accent between dialects. In most of Eastern Norway, including the capital Oslo, the so-called low pitch dialects are spoken. In these dialects, accent 1 uses a low flat pitch in the first syllable, while accent 2 uses a high, sharply falling pitch in the first syllable and a low pitch in the beginning of the second syllable. In both accents, these pitch movements are followed by a rise of intonational nature (phrase accent), the size (and presence) of which signals emphasis/focus and which corresponds in function to the normal accent in languages that lack lexical tone, such as English. That rise culminates in the final syllable of an accentual phrase, while the fall to utterance-final low pitch that is so common in most languages[99] is either very small or absent.

On the other hand, in most of western and northern Norway (the so-called high-pitch dialects) accent 1 is falling, while accent 2 is rising in the first syllable and falling in the second syllable or somewhere around the syllable boundary. The two tones can be transcribed on the first vowel as /ɑ̀/ for accent 1 and /ɑ̂/ for accent 2; the modern reading of the IPA (low and falling) corresponds to eastern Norway, whereas an older tradition of using diacritics to represent the shape of the pitch trace (falling and rising-falling) corresponds to western Norway.

The pitch accents (as well as the peculiar phrase accent in the low-tone dialects) give the Norwegian language a "singing" quality which makes it fairly easy to distinguish from other languages. Accent 1 generally occurs in words that were monosyllabic in Old Norse, and accent 2 in words that were polysyllabic.

Tonal accents and morphology

In many dialects, the accents take on a significant role in marking grammatical categories. Thus, the ending (T1)—en implies determinate form of a masculine monosyllabic noun (båten 'boat', bilen, 'car'), whereas (T2)-en denotes either determinate form of a masculine bisyllabic noun or an adjectivised noun/verb (moden 'mature'). Similarly, the ending (T1)—a denotes feminine singular determinate monosyllabic nouns (boka 'book', rota 'root') or neuter plural determinate nouns (husa 'houses', lysa 'lights'), whereas the ending (T2)—a denotes the preterite of weak verbs (rota 'made a mess', husa 'housed'), feminine singular determinate bisyllabic nouns (bøtta 'bucket', ruta 'square').

In Eastern Norwegian the tone difference may also be applied to groups of words, with different meaning as a result. Gro igjen for example, means 'grow anew' when pronounced with tone 1 [ˈɡɾùː‿ijə́n], but 'grow over' when pronounced with tone 2 [ˈɡɾûː‿ijə́n]. In other parts of Norway, this difference is achieved instead by the shift of stress (gro igjen [ˈɡɾuː ijən] vs. gro igjen [ɡɾuː ˈijən]).

In compound words

In a compound word, the pitch accent is lost on one of the elements of the compound (the one with weaker or secondary stress), but the erstwhile tonic syllable retains the full length (long vowel or geminate consonant) of a stressed syllable.[100]

Monosyllabic tonal accents

In some dialects of Norwegian, mainly those from Nordmøre and Trøndelag to Lofoten, there may also be tonal opposition in monosyllables, as in [bîːl] ('car') vs. [bìːl] ('axe'). In a few dialects, mainly in and near Nordmøre, the monosyllabic tonal opposition is also represented in final syllables with secondary stress, as well as double tone designated to single syllables of primary stress in polysyllabic words. In practice, this means that one gets minimal pairs like: [hɑ̀ːniɲː] ('the rooster') vs. [hɑ̀ːnîɲː] ('get him inside'); [brŷɲːa] ('in the well') vs. [brŷɲːâ] ('her well'); [læ̂nsmɑɲː] ('sheriff') vs. [læ̂nsmɑ̂ɲː] ('the sheriff'). Amongst the various views on how to interpret this situation, the most promising one may be that the words displaying these complex tones have an extra mora. This mora may have little or no effect on duration and dynamic stress, but is represented as a tonal dip.

Other dialects with tonal opposition in monosyllabic words have done away with vowel length opposition. Thus, the words [vɔ̀ːɡ] ('dare') vs. [vɔ̀ɡː] ('cradle') have merged into [vɔ̀ːɡ] in the dialect of Oppdal.

Loss of tonal accents

Some forms of Norwegian have lost the tonal accent opposition. This includes mainly parts of the area around (but not including) Bergen; the Brønnøysund area; to some extent, the dialect of Bodø; and, also to various degrees, many dialects between Tromsø and the Russian border. Faroese and Icelandic, which have their main historical origin in Old Norse, also show no tonal opposition. It is, however, not clear whether these languages lost the tonal accent or whether the tonal accent was not yet there when these languages started their separate development. Standard Danish, Rigsdansk, replaces tonal accents with the stød, whilst some southern, insular dialects of Danish preserve the tonal accent to different degrees. The Finland Swedish dialects also lack a tonal accent, as no such phenomenon exists in Finnish.

Pulmonic ingressive

The words ja ('yes') and nei ('nei') are sometimes pronounced with inhaled breath (pulmonic ingressive) in Norwegian—and this can be rather confusing for foreigners. The same phenomenon occurs across the other Scandinavian languages, and can also be found in German, French, Finnish and Japanese, to name a few.

Sample

The sample text is a reading of the first sentence of The North Wind and the Sun by a 47-year-old professor from Oslo's Nordstrand district.[101]

Phonemic transcription

/²nuːɾɑˌʋinen ɔ ˈsuːlen ²kɾɑŋlet ɔm ʋem ɑ dem sem ˈʋɑːɾ den ²stæɾkeste/

Phonetic transcription

[²nuːɾɑˌʋinˑn̩ ɔ ˈsuːln̩ ²kɾɑŋlət ɔm ʋem ɑ dem sɱ̍ ˈʋɑː ɖɳ̍ ²stæɾ̥kəstə][102]

Orthographic version

Nordavinden og solen kranglet om hvem av dem som var den sterkeste.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 Kristoffersen (2000), p. 22.

- ↑ Skaug (2003), pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 58.

- ↑ Vanvik (1979), p. 40.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 75–76, 79.

- 1 2 3 Kristoffersen (2000), p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Vanvik (1979), p. 41.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Endresen (1990:177), cited in Kristoffersen (2000:25)

- 1 2 Kristoffersen (2000), p. 24.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), p. 23.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 6–11.

- ↑ Grønnum (2005), p. 155.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kristoffersen (2000), p. 19.

- ↑ Vanvik (1979), pp. 14, 17, 19-20.

- ↑ Strandskogen (1979), p. 16.

- ↑ Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005), pp. 4–5.

- ↑ For example by Haugen (1974), Vanvik (1979), Kristoffersen (2000), Skaug (2003) or Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005).

- ↑ Sources that transcribe /i, y, u/ with ⟨i, y, u⟩ include Haugen (1974), Vanvik (1979) and Skaug (2003). Kristoffersen (2000) also uses ⟨i, y, u⟩, but admits that ⟨ɪ, ʏ, ʊ⟩ is just as correct a transcription (see p. 11). Sources that transcribe /i, y, u/ with ⟨ɪ, ʏ, ʊ⟩ include Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005).

- 1 2 Such as Haugen (1974).

- ↑ For example by Haugen (1974), Vanvik (1979), Skaug (2003) or Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005). Kristoffersen (2000) also uses ⟨ʉ⟩, but admits that ⟨ʉ̞⟩ is just as correct a transcription (see p. 11).

- ↑ ⟨ʉ̞⟩ is mentioned by Kristoffersen (2000) as a symbol that is just as equally correct as ⟨ʉ⟩.

- ↑ Used by e.g. Krech et al. (2009).

- ↑ For example by Vanvik (1979), Kristoffersen (2000), Skaug (2003), Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005) or Krech et al. (2009).

- ↑ For example by Vanvik (1979) and Skaug (2003).

- ↑ For example by Kristoffersen (2000) and Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005)

- ↑ For example by Haugen (1974), Vanvik (1979), Skaug (2003), Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005) and Krech et al. (2009).

- ↑ For example by Haugen (1974), Kristoffersen (2000), Skaug (2003), Kvifte & Gude-Husken (2005) and Krech et al. (2009).

- ↑ Such as Berulfsen (1969), Strandskogen (1979) and Popperwell (2010)

- 1 2 3 4 Berulfsen (1969).

- 1 2 3 4 Strandskogen (1979).

- 1 2 3 4 Popperwell (2010).

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Lexin". Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Such as Vanvik (1979).

- ↑ Such as Popperwell (2010).

- 1 2 3 Vanvik (1979), pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 18.

- 1 2 3 4 Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15-16.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 18.

- 1 2 Popperwell (2010), p. 16.

- 1 2 Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15, 23.

- 1 2 3 4 Vanvik (1979), pp. 13, 20.

- 1 2 Popperwell (2010), pp. 32, 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Haugen (1974), p. 40.

- 1 2 Kristoffersen (2000), p. 15.

- 1 2 Vanvik (1979), pp. 13, 19.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 32.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 32.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 30–31.

- 1 2 Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15, 21.

- 1 2 3 4 Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 29, 31.

- 1 2 Vanvik (1979), pp. 13, 18.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 29.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 29.

- 1 2 Popperwell (2010), pp. 27-28.

- 1 2 Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15, 20.

- 1 2 Kristoffersen (2000), p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Vanvik (1979), pp. 13, 17.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 27.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 27.

- 1 2 Vanvik (1979), pp. 13, 15.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 20.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 20-21.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 26, 31–32.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 19.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 19.

- 1 2 Popperwell (2010), pp. 35-36.

- 1 2 Strandskogen (1979), p. 23.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 16–17, 21.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 16–17, 33–35, 37, 343.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 35.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 35.

- 1 2 Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15, 19.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 26.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 25.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), p. 25.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 21–22.

- 1 2 Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15, 18.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 14, 106.

- ↑ Berulfsen (1969), p. 10.

- ↑ Skaug (2003), pp. 15–19.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 16, 23–24.

- ↑ Popperwell (2010), pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Vanvik (1979), pp. 13, 15–16.

- ↑ Vanvik (1979), p. 16.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 16–17, 25.

- ↑ Vanvik (1979), p. 22.

- ↑ Strandskogen (1979), pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), pp. 19, 25.

- ↑ Gussenhoven (2004), p. 89.

- ↑ Kristoffersen (2000), p. 184.

- ↑ "Nordavinden og sola: Opptak og transkripsjoner av norske dialekter".

- ↑ Source of the phonetic transcription: "Nordavinden og sola: Opptak og transkripsjoner av norske dialekter".

References

- Berulfsen, Bjarne (1969), Norsk Uttaleordbok, Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co (W Nygaard)

- Endresen, Rolf Theil (1990), "Svar på anmeldelser av Fonetikk. Ei elementær innføring.", Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap, Oslo: Novus forlag: 169–192

- Grønnum, Nina (2005), Fonetik og fonologi, Almen og Dansk (3rd ed.), Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, ISBN 87-500-3865-6

- Gussenhoven, Carlos (2004), The Phonology of Tone and Intonation, Cambridge University Press

- Haugen, Einar (1974) [1965], Norwegian-English Dictionary, The University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-03874-2

- Krech, Eva Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz-Christian (2009), "7.3.10 Norwegisch", Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch, Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6

- Kristoffersen, Gjert (2000), The Phonology of Norwegian, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-823765-5

- Kvifte, Bjørn; Gude-Husken, Verena (2005) [First published 1997], Praktische Grammatik der norwegischen Sprache (3rd ed.), Gottfried Egert Verlag, ISBN 3-926972-54-8

- Popperwell, Ronald G. (2010) [First published 1963], Pronunciation of Norwegian, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-15742-1

- Riad, Tomas (2014), The Phonology of Swedish, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-954357-1

- Skaug, Ingebjørg (2003) [First published 1996], Norsk språklydlære med øvelser (3rd ed.), Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk Forlag AS, ISBN 82-456-0178-0

- Strandskogen, Åse-Berit (1979), Norsk fonetikk for utlendinger, Oslo: Gyldendal, ISBN 82-05-10107-8

- Vanvik, Arne (1979), Norsk fonetikk, Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo, ISBN 82-990584-0-6

Further reading

- Endresen, Rolf Theil (1977), "An Alternative Theory of Stress and Tonemes in Eastern Norwegian", Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap, 31: 21–46

- Lundskær-Nielsen, Tom; Barnes, Michael; Lindskog, Annika (2005), Introduction to Scandinavian phonetics: Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish, Alfabeta, ISBN 978-8763600095

- Haugen, Einer (1967). "On the Rules of Norwegian Tonality". Language Vol. 43, No. 1 (Mar., 1967), pp. 185-202.

- Torp, Arne (2001), "Retroflex consonants and dorsal /r/: mutually excluding innovations? On the diffusion of dorsal /r/ in Scandinavian", in van de Velde, Hans; van Hout, Roeland, 'r-atics, Brussels: Etudes & Travaux, pp. 75–90, ISSN 0777-3692

- Vanvik, Arne (1985), Norsk Uttaleordbok: A Norwegian pronouncing dictionary, Oslo: Fonetisk institutt, Universitetet i Oslo, ISBN 978-8299058414

- Wetterlin, Allison (2010), Tonal Accents in Norwegian: Phonology, morphology and lexical specification, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-023438-1