Sidewalk clock on Jamaica Avenue

|

Sidewalk Clock at 161-10 Jamaica Avenue, New York, NY | |

|

Historic street clock at Jamaica Avenue and Union Hall Street | |

| |

| Location | 92-00a Union Hall Street, Jamaica, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°42′15″N 73°47′53″W / 40.70417°N 73.79806°WCoordinates: 40°42′15″N 73°47′53″W / 40.70417°N 73.79806°W |

| MPS | Sidewalk Clocks of New York City TR |

| NRHP reference # | 85000931[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 18, 1985 |

| Designated NYCL | August 25, 1981 |

The sidewalk clock originally at 161-11 Jamaica Avenue in Jamaica, Queens, New York City is a historic cast iron sidewalk clock. Its design incorporates a bell-cast shaped column base and an anthemion finial above the dial casing.[2]

The early 20th century clock is located on the southwest corner of Jamaica Avenue and Union Hall Street.[3] The corner is the site of a Chase Manhattan Bank Building which was previously the site of a former pre-colonial stone church that existed from 1699 to 1813, and which was converted into a prison during the American Revolution.[4] The clock was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985 and installed at this site in 1989.[1]

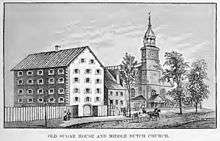

Old stone church

The village of Jamaica, settled by a band of English people, was granted a charter for “Rustdorp” by Governor Stuyvesant in 1656. Six years later, about 25 families of these settlers joined together to make this church. At a town meeting the same year it was voted to build a parsonage, 26ft. long and 17ft. wide, a large house for the time and place, the whole town being assessed for the cost. This parsonage served as the house for a few years until the town church was built in the last decade of the 17th century. The new meeting house was variously called : “The Town Church,” “The Stone Church” and “The Church.” It stood on the main street of the village not far from the present corner of Fulton Street and New York Avenue (Guy Brewer) at the head of Meeting House Lane (Union Hall St.)

It was used by all congregations for worship, as a town hall and as a court house for many years. For most of the 18th century the “Old Trail” along Jamaica avenue would make this area a trading post for farmers and their produce, with horse-drawn carts found up and down “Kings Highway”.[6]

When Lord Cornbury became governor, he placed the church and the parsonage at the disposal of the congregation of the Church of England on the grounds that the building had been paid for by public taxation. The Episcopalians then refused the other congregations the use of it. Whereupon, the Presbyterians brought suit and recovered both the parsonage and the church, which they continued to use until the new building was built in 1813. In the foundations of this building on 163rd st are some of the stones of the old church.[7] [8]

Jamaica Avenue clock

Originally erected in 1900 at 161-11 Jamaica Avenue, the clock was designated a New York City landmark in 1981. It is double-faced with a cast-iron paneled base, fluted column post, and splendid acroteria motif crowning the clock face. It was restored and moved to its present location at 92-00a Union Hall Street in 1989. The descriptive plaque was installed in the wall of the bank building below the one placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution for the Old stone church. Originally placed in front of Busch's Jewellers, it is 15 feet high to the top of the finial, and was similar to other cast-iron post (tower) clocks produced between 1881 and 1910 by the E. Howard Clock Company and the Seth Thomas Clock Company.

The clocks were manufactured and sold from catalogs for about $600 (equivalent to $15,215 in 2017) and had weight-driven mechanisms, so there is no relation to installed date and date of manufacture. They operated for approximately 8 days calculated according to the distance in feet needed for a weight to fall after it was wound up to the top of the mechanism. Designs varied, with 2 and 4 faced clocks being typical, the basic compositions were mounted on classical columns and bases. The description for the Jamaica clock: "double-faced sidewalk clock with a paneled base, fluted column post on a bell-shaped pedestal with an anthemion Finial motif above the clock-face" describes one that was not in the Howard or Seth Thomas catalogs and may be from a different manufacturer. One possible source is the Hecla Iron Works of Williamsburg.[9]

At one point in the clock's lifetime the words 'Tad's Steaks' were added in neon and subsequently removed during restoration. The anthemion finial was used in neo-classical Greek and Roman architecture to embellish various parts of ancient buildings. The fronds of an anthemion, which means honeysuckle, tend to curl inward.[10][11]

Other clocks

Representing a period of significance from 1880-1930, the six intact landmarked sidewalk clocks in New York City (five in Manhattan and one in Queens) were a mode of advertising sponsored by the businesses they were placed in front of. They are examples of cast-iron street furniture distinguished by their architectonic quality, employing classical orders and decorative motifs in their designs. Intended to provide visual interest to the street they provided a period character to the sidewalks with which they are associated. The second clock in Queens, located on Steinway Street in Astoria, is not landmarked due to significant changes to the original.

Sidewalk clocks, also known as post clocks, were introduced to American Cities in the mid-nineteenth century. Although they trace their mechanical ancestry to the great medieval tower clocks of Europe, the design and commercial use of timepieces within free-standing cast-iron cases appears to be a primarily American Horological development. By the 1950's, sidewalk clocks came to be regarded by many as old-fashioned and obsolete, and many were removed in the name of beautification, modernization and improved pedestrian circulation.

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Mark L. Peckham (December 1984). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Sidewalk Clocks of New York City Thematic Resources". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ↑ http://www.neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb_files/81-161-11-SIDEWWALK-CLOCK.pdf

- ↑ DanTD (June 10, 2013). Jamaica, Queens; Old Stone Church Plaque (photograph). Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ↑ Lewis, Charles H. (2009). Cut Off: Colonel Jedediah Huntington's 17th Continental (Conn.) Regiment at the Battle of Long Island August 27, 1776. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-7884-4924-6.

- ↑ https://gjdc.org/our-story/jamaica-history/

- ↑ https://www.jstor/stable/43564781

- ↑ historical sketch of the first Presbyterian church in Jamaica, new York, Anna Elizabeth Foote – Quarterly journal of the New York State historical association vol 5 no.4 (October, 1924) , pp.342-343 pub by Fenimore Art Museum

- ↑ https://www.brownstoner.com/architecture/brooklyn-architecture-williamsburg-hecla-iron-works-110-north-11th-street/

- ↑ https://www.marymaycarving.com/carvingschool/2018/02/14/carving-an-anthemion/

- ↑ https://www.decorartsnow.com/design-dictionary-anthemion-and-palmette/

External links

- Report, Landmarks Preservation Commission, 1981

- Flickr.com