Saint-Malo

| Saint-Malo Saent-Malô | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subprefecture and commune | |||

Walled city | |||

| |||

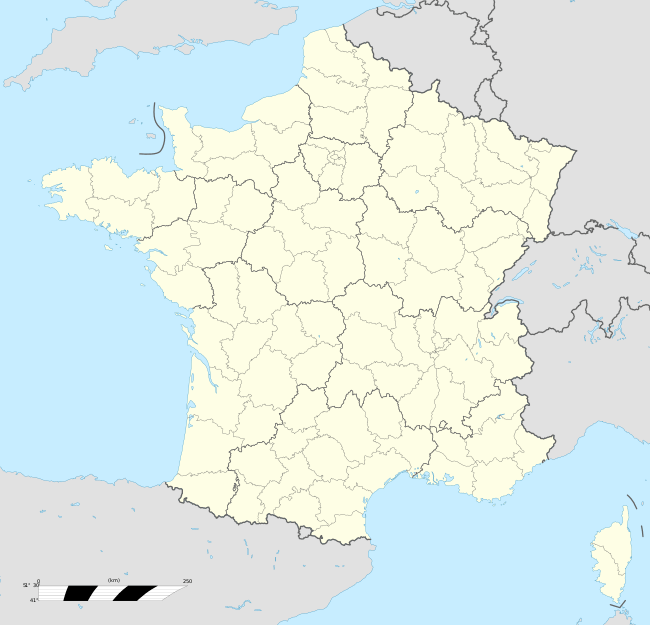

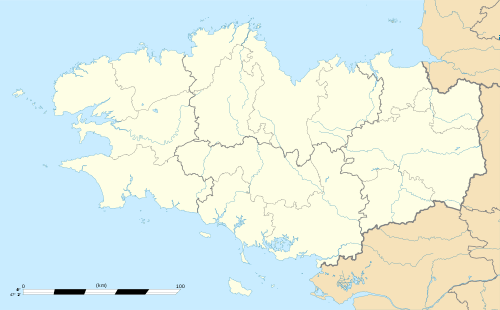

Saint-Malo Location within Brittany region  Saint-Malo | |||

| Coordinates: 48°38′53″N 2°00′27″W / 48.6481°N 2.0075°WCoordinates: 48°38′53″N 2°00′27″W / 48.6481°N 2.0075°W | |||

| Country | France | ||

| Region | Brittany | ||

| Department | Ille-et-Vilaine | ||

| Arrondissement | Saint-Malo | ||

| Canton | Saint-Malo-1 and 2 | ||

| Intercommunality | CA Pays de Saint-Malo | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor (2014–2020) | Claude Renoult | ||

| Area1 | 36.58 km2 (14.12 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2012)2 | 44,620 | ||

| • Density | 1,200/km2 (3,200/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| INSEE/Postal code | 35288 /35400 | ||

| Elevation |

0–51 m (0–167 ft) (avg. 8 m or 26 ft) | ||

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | |||

Saint-Malo (French pronunciation: [sɛ̃.ma.lo]; Gallo: Saent-Malô; Breton: Sant-Maloù) is a historic French port in Brittany on the Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the Allies heavily bombarded Saint-Malo, mistaking it for a major enemy base. Today it is a popular tourist centre, with a ferry terminal serving Portsmouth, Weymouth, and Poole.

Population

The population, in 2012, was 44,620 – though this can increase to up to 200,000 in the summer tourist season. With the suburbs included, the metropolitan area's population is approximately 153,000 (2011).

The population of the commune more than doubled in 1968 with the merging of three communes: Saint-Malo, Saint-Servan (population 14,963 in 1962) and Paramé (population 8,811 in 1962).

Inhabitants of Saint-Malo are called Malouins in French. From this came the Spanish name for the Islas Malvinas, the archipelago known in English as the Falkland Islands. Islas Malvinas derives from the 1764 name Îles Malouines, given to the islands by French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville.[1] Bougainville, who founded the archipelago's first settlement, named the islands after the inhabitants of Saint-Malo, the point of departure for his ships and colonists.[1]

History

Founded by Gauls in the 1st century B.C. The ancient town on the site of Saint-Malo was known as the Roman Reginca or Aletum. By the late 4th century AD the Saint-Servan district was the site of a major Saxon Shore promontory fort that protected the Rance river estuary from seaborne raiders from beyond the frontiers. According to the Notitia Dignitatum the fort was garrisoned by the militum Martensium under a dux (commander) of the Tractus Armoricanus and Nervicanus section of the litus Saxonicum. During the decline of the Western Roman Empire Armorica (modern day Brittany) rebelled from Roman rule under the Bagaudae and in the 5th and 6th centuries received many Celtic Britons fleeing instability across the Channel. The modern Saint-Malo traces its origins to a monastic settlement founded by Saint Aaron and Saint Brendan early in the sixth century. Its name is derived from a man said to have been a follower of Brendan the Navigator, Saint Malo or Maclou, an immigrant from what is now Wales.

Saint-Malo is the setting of Marie de France's poem "Laustic," an 11th-century love story. The city had a tradition of asserting its autonomy in dealings with the French authorities and even with the local Breton authorities. From 1590 to 1593, Saint-Malo declared itself to be an independent republic, taking the motto "not French, not Breton, but Malouin."[2]

Saint-Malo became notorious as the home of the corsairs, French privateers and sometimes pirates. In the 19th century, this "piratical" notoriety was portrayed in Jean Richepin's play Le flibustier and in César Cui's eponymous opera. The corsairs of Saint-Malo not only forced English ships passing up the Channel to pay tribute, but also brought wealth from further afield. Jacques Cartier, who sailed the Saint Lawrence River and visited the sites of Quebec City and Montreal, and is thus credited as the discoverer of Canada, lived in and sailed from Saint-Malo, as did the first colonists to settle the Falkland Islands, hence the Islands' French name "Îles Malouines," which eventually gave rise to the Spanish name "Islas Malvinas." In 1758, the Raid on St Malo saw a British expedition land intending to capture the town. However, the British made no attempt on Saint-Malo, and instead occupied the nearby town of Saint-Servan, where they destroyed 30 privateers before departing.

In World War II, during fighting in late August and early September 1944, the historic walled city of Saint-Malo was almost totally destroyed by American shelling and bombing as well as British naval gunfire.[3][4] The Allies believed that the Axis powers had thousands of troops and major armaments built up within the city walls – though there proved to be fewer than 100 troops manning just two anti-aircraft installations, with the much larger and heavily armed Axis presence in strongpoints outside the city walls.[5] The Americans used napalm for the first time.[6] Saint-Malo was rebuilt over a 12-year period from 1948 to 1960.

Saint-Malo is a subprefecture of the Ille-et-Vilaine. The commune of Saint-Servan was merged, together with Paramé, and became the commune of Saint-Malo in 1967.

Saint-Malo was the site of an Anglo-French summit in 1998 that led to a significant agreement regarding European defence policy.

Climate

| Climate data for Dinard | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

35.4 (95.7) |

39.4 (102.9) |

33.1 (91.6) |

28.9 (84) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.6 (63.7) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.0 (68) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.1 (43) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.7 (7.3) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−2.8 (27) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

5.0 (41) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 67.0 (2.638) |

57.6 (2.268) |

53.5 (2.106) |

53.0 (2.087) |

63.6 (2.504) |

49.1 (1.933) |

49.7 (1.957) |

49.4 (1.945) |

62.2 (2.449) |

86.8 (3.417) |

86.8 (3.417) |

80.0 (3.15) |

758.7 (29.87) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.6 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 9.7 | 13.6 | 13.8 | 13.4 | 129.5 |

| Average snowy days | 1.7 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 7.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 81 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 82 | 85 | 84 | 85 | 81.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 69.5 | 84.3 | 127.5 | 164.1 | 188.4 | 206.4 | 206.4 | 198.6 | 167.1 | 112.6 | 77.8 | 64.0 | 1,666.6 |

| Source #1: Meteo France (1981-2010, sunshine 1991-2010) [7][8] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity, snowy days 1961–1990)[9] | |||||||||||||

Education

Schools

Schools include:

- 13 public preschools (écoles maternelles)[10]

- 11 public elementary schools[11]

- 8 private preschools and elementary schools[12]

- 4 public junior high schools: Chateaubriand, Duguay-Trouin, Robert Surcouf, and Charcot[13]

- 3 private junior high schools: Choisy Jeanne d’Arc, Moka, and Sacré-Cœur[14]

- 3 public senior high schools: Lycee Maupertuis, Lycee Jacques Cartier, Professional Maritime Lycee Les Rimains[15]

- 2 private senior high schools: Lycee Institution Saint Malo-La Providence and Les Rimains[16]

Higher education

- Institute of Technology of Saint-Malo

- A nurse school,

- A maritime school

Transport

Saint-Malo has a terminal for ferry services with daily departures to Portsmouth operated by Brittany Ferries[17] and services on most days Poole and Weymouth in England via the Channel Islands operated by Condor Ferries.[18] It also has a railway station, Gare de Saint-Malo, offering direct TGV service to Rennes, Paris and several regional destinations. There is a bus service provided by Keolis. The town is served by the Dinard–Pleurtuit–Saint-Malo Airport around 5 kilometres (3 miles) to the south.

Sites of interest

Now inseparably attached to the mainland, Saint-Malo is the most visited place in Brittany. Sites of interest include:

- The walled city (La Ville Intra-Muros)

- The château of Saint-Malo, part of which is now the town museum.

- The Solidor Tower in Saint-Servan is a 14th-century building that holds a collection tracing the history of voyages around Cape Horn. Many scale models, nautical instruments and objects made by the sailors during their crossing or brought back from foreign ports invoke thoughts of travel aboard extraordinary tall ships at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

- The tomb of the writer Chateaubriand on the Ile du Grand Bé

- The Petit Bé

- The Cathedral of St. Vincent (Saint-Malo Cathedral)

- The Privateer's House ("La Demeure de Corsaire"), a ship-owner's town house built in 1725, shows objects from the history of privateering, weaponry and ship models.

- The Great Aquarium Saint-Malo, one of the major aquaria in France.

- The labyrinthe du Corsaire, (an attraction park in Saint Malo)

- The Pointe de la Varde, Natural Park.

- The City of Alet, in front of Saint Malo Intra Muros.

- Fort National

- Fort de la Conchée

Personalities

Saint-Malo was the birthplace of:

- Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), explorer of Canada

- Jacques Gouin de Beauchene (1652–1730), explorer of the Falkland Islands

- René Duguay-Trouin (1673–1736) French corsair and Admiral who captured the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1711

- Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698–1759), mathematician and astronomer

- Bertrand-François Mahé de La Bourdonnais (1699–1753), sailor and administrator

- Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709–1751), physician and philosopher

- Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne (1724–1772), explorer

- Joseph Quesnel (1746-1809), Canadian poet, composer and playwright

- Louis de Grandpré (1761-1846) French Navy officer and slave trader[19]

- François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848), writer and diplomat

- Robert Surcouf (1773–1827), sailor, trader, ship-owner and corsair

- Hughes Felicité Robert de Lamennais (1782–1854), priest, philosophical and political writer

- Louis Duchesne (1843–1922), historian, French academician

- Alfred Blunt (1879-1957), Anglican Bishop of Bradford, England, was born at St Malo of British expatriate parents and brought up there until the family returned to England in 1887.

- Philippe Cattiau (1892–1962), Olympic medalist in fencing

- Colin Clive (1900–1937), actor

- Jean Lebrun (born 1950), journalist and radio producer

Twin towns – sister cities

Saint-Malo is twinned with:

Gallery

Street view of classic road in Saint-Malo

Street view of classic road in Saint-Malo.jpg) From the fort of Saint-Malo

From the fort of Saint-Malo.jpg) The "Fort National" visible from Saint-Malo

The "Fort National" visible from Saint-Malo View up a typical city street towards the cathedral

View up a typical city street towards the cathedral Cathedral window

Cathedral window- The city wall of St Malo.

- Commemoration of the Cartier expedition in the floor of the cathedral.

In popular culture

Much of the action in Anthony Doerr's 2014 award-winning novel, All the Light We Cannot See, occurs in Saint-Malo.

See also

References

- 1 2 Hince, Bernadette (2001). The Antarctic Dictionary. Collingwood, Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-9577471-1-1.

- ↑ S. and J. Beaulieu, Saint-Malo et l'histoire, p 10 to 32

- ↑ "Key Dates". Saint-Malo official website. .

- ↑ "Brittany Campaign - Rolland Despres, 4th platoon, B Company, 1 Bn, 331st IR, 83rd Infantry Division". www.angelfire.com.

- ↑ Beck, Philip (Winter 1981). "The Burning of Saint Malo". Journal of Historical Review. Institute for Historical Review. 2 (4): 301–304. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- ↑ Lee Miller, Portraits from a Life, p.92

- ↑ "Données climatiques de la station de Dinard" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Climat Bretagne" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Normes et records 1961-1990: Dinard - St Malo (35) - altitude 58m" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Ecoles maternelles publiques." Saint-Malo. Retrieved on September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Ecoles élémentaires publiques." Saint-Malo. Retrieved on September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Ecoles privées élémentaires et maternelles." Saint-Malo. Retrieved on September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Collèges publics." Saint-Malo. Retrieved on September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Collèges privés." Saint-Malo. Retrieved on September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Lycées publics." Saint-Malo. Retrieved on September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Lycées privés." Saint-Malo. Retrieved on September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Portsmouth to St Malo". Brittany Ferries.

- ↑ "St. Malo destination guides". Condor Ferries. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ↑ Ripley, George & Dana, Charles Anderson (2010). The New American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge. 8. Nabu Press. pp. 410–411. ISBN 978-1146913317.

- ↑ "International collaboration". gmiezno.eu. Gniezno. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- INSEE

- Mayors of Ille-et-Vilaine Association (in French)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint-Malo. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Saint-Malo. |

- Town hall's website (in French)

- French Ministry of Culture list for Saint-Malo (in French)

- Public transport of Saint-Malo (in French)

- Saint-Malo France Independent travel guide to the historic city of Saint-Malo. (in English)

.svg.png)