Tretinoin

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | See pronunciation note |

| Trade names | Vesanoid, Avita, Renova, Retin-a, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682437 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | topical, by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | > 95% |

| Elimination half-life | 0.5-2 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.005.573 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

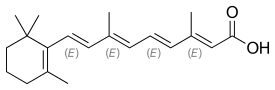

| Formula | C20H28O2 |

| Molar mass | 300.4412 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 180 °C (356 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Tretinoin, also known as all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), is medication used for the treatment of acne and acute promyelocytic leukemia.[1][2][3] For acne, it is applied to the skin as a cream or ointment.[3] For leukemia, it is taken by mouth for up to three months.[1]

Common side effects when used by mouth include shortness of breath, headache, numbness, depression, skin dryness, itchiness, hair loss, vomiting, muscle pains, and vision changes.[1] Other severe side effects include high white blood cell counts and blood clots.[1] When used as a cream, side effects include skin redness, peeling, and sun sensitivity.[3] Use during pregnancy is known to harm the baby.[1] It is in the retinoid family of medications.[2]

Tretinoin was patented in 1957 and approved for medical use in 1962.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[5] Tretinoin is available as a generic medication.[6] In the United Kingdom the cream together with erythromycin costs the NHS about £7.05 per 25 mL while the pills are £1.61 per 10 mg.[3]

Medical uses

Skin use

Tretinoin is most commonly used to treat acne.[7] It is also used off-label to treat and reduce the appearance of stretch marks by increasing collagen production in the dermis.[8]

In topical form, this drug is pregnancy category C and should not be used by pregnant women.[7]

People using the topical form should not also use any cream or lotion that has a strong drying effect, contains alcohol, astringents, spices, lime, sulfur, resorcinol, or aspirin, as these may interact with tretinoin or exacerbate its side effects.[7]

Leukemia

Tretinoin is used to induce remission in people with acute promyelocytic leukemia who have a mutation (the t(15;17) translocation 160 and/or the presence of the PML/RARα gene) and who don't respond to anthracyclines or can't take that class of drug. It is not used for maintenance therapy.[9][10][11]

In oral form, this drug is pregnancy category D and should not be used by pregnant women as it may harm the fetus.[9]

Side effects

Skin use

Topical tretinoin is only for use on skin and it should not be applied to eyes or mucosal tissues. Common side effects include skin irritation, redness, swelling, and blistering.[7]

Leukemia use

The oral form of the drug has boxed warnings concerning the risks of retinoic acid syndrome and leukocytosis.[9]

Other significant side effects include a risk of thrombosis, benign intracranial hypertension in children, high lipids (hypercholesterolemia and/or hypertriglyceridemia), and liver damage.[9]

There are many significant side effects from this drug that include malaise (66%), shivering (63%), hemorrhage (60%), infections (58%), peripheral edema (52%), pain (37%), chest discomfort (32%), edema (29%), disseminated intravascular coagulation (26%), weight increase (23%), injection site reactions (17%), anorexia (17%), weight decrease (17%), and myalgia (14%).[9]

Respiratory side effects usually signify retinoic acid syndrome, and include upper respiratory tract disorders (63%), dyspnea (60%), respiratory insufficiency (26%), pleural effusion (20%), pneumonia (14%), rales (14%), and expiratory wheezing (14%), and many others at less than 10%.[9]

Around 23% of people taking the drug have reported eararche or a feeling of fullness in their ears.[9]

Gastrointestinal disorders include bleeding (34%), abdominal pain (31%), diarrhea (23%), constipation (17%), dyspepsia (14%), and swollen belly (11%) and many others at less than 10%.[9]

In the cardiovascular system, side effects include arrhythmias (23%), flushing (23%), hypotension (14%), hypertension (11%), phlebitis (11%), and cardiac failure (6%) and for 3% of patients: cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, enlarged heart, heart murmur, ischemia, stroke, myocarditis, pericarditis, pulmonary hypertension, secondary cardiomyopathy.[9]

In the nervous system, side effects include dizziness (20%), paresthesias (17%), anxiety (17%), insomnia (14%), depression (14%), confusion (11%), and many others at less than 10% frequency.[9]

In the urinary system, side effects include renal insufficiency (11%) and several others at less than 10% frequency.[9]

Mechanism of action

For its use in cancer, its mechanism of action is unknown, but on a cellular level, laboratory test show that tretinoin forces APL cells to differentiate and stops them from proliferating; in people there is evidence that it forces the primary cancerous promyelocytes to differentiate into their final form, allowing normal cells to take over the bone marrow.[9] Recent study shows that ATRA inhibits and degrades active PIN1.[12]

For its use in acne, the mechanism is unknown, but again on a cellular level there is evidence that it decreases the ability of epithelial cells in hair follicles to stick together, leading to fewer blackheads; it also seems to make the epithelial cells divide faster, causing the blackheads to be pushed out.

History

Tretinoin was co-developed for its use in acne by James Fulton and Albert Kligman when they were at University of Pennsylvania in the late 1960s.[13][14] The University of Pennsylvania held the patent for Retin-A, which it licensed to pharmaceutical companies.[14]

Etymology

The origin of the name tretinoin is uncertain,[15][16] although several sources agree (one with probability,[15] one with asserted certainty[17]) that it probably comes from trans- + retinoic [acid] + -in, which is plausible given that tretinoin is the all-trans isomer of retinoic acid. The name isotretinoin is the same root tretinoin plus the prefix iso-. Regarding pronunciation, the following variants apply equally to both tretinoin and isotretinoin. Given that retinoic is pronounced /ˌrɛtɪˈnoʊɪk/,[16][17][18][19] it is natural that /ˌtrɛtɪˈnoʊɪn/ is a commonly heard pronunciation. Dictionary transcriptions also include /ˌtrɪˈtɪnoʊɪn/ (tri-TIN-oh-in)[16][18] and /ˈtrɛtɪnɔɪn/.[17][19]

Research

Tretinoin has been explored as a treatment for hair loss, potentially as a way to increase the ability of minoxidil to penetrate the scalp, but the evidence is weak and contradictory.[20][21]

See also

- Baldness treatments

- Hypervitaminosis A syndrome

- Talarozole, an experimental drug potentiating the effects of tretinoin

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tretinoin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Tivnan, Amanda (2016). Resistance to Targeted Therapies Against Adult Brain Cancers. Springer. p. 123. ISBN 9783319465050. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- 1 2 3 4 British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 627, 821–822. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 476. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Tretinoin topical". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Topical Cream Gel Liquid Label Archived 2011-12-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Arthur W. Perry (2007). Straight talk about cosmetic surgery. Yale University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-300-12104-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Oral Label Archived 2016-05-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Huang M, Ye Y, Chen S, Chai J, Lu J, Zhoa L, Gu L, Wang Z (1988). "Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia" (PDF). Blood. 72 (2): 567–72. PMID 3165295.

- ↑ Castaigne S, Chomienne C, Daniel M, Ballerini P, Berger R, Fenaux P, Degos L (1990). "All-trans retinoic acid as a differentiation therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia. I. Clinical results" (PDF). Blood. 76 (9): 1704–9. PMID 2224119.

- ↑ Wei, Shuo; Kozono, Shingo; Kats, Lev; Nechama, Morris; Li, Wenzong; Guarnerio, Jlenia; Luo, Manli; You, Mi-Hyeon; Yao, Yandan (May 2015). "Active Pin1 is a key target of all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia and breast cancer". Nature Medicine. 21 (5): 457–466. doi:10.1038/nm.3839. ISSN 1546-170X.

- ↑ Vivant Pharmaceuticals, LLC Press Release. July 10, 2013, Vivant Skin Care Co-founder James E. Fulton, MD, Loses Colon Cancer Battle

- 1 2 Denis Gellene for the New York Times. Feb 22, 2010. Dr. Albert M. Kligman, Dermatologist, Dies at 93 Archived 2017-11-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Unabridged Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.

- 1 2 3 Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford Dictionaries Online, Oxford University Press, archived from the original on 2014-10-22.

- 1 2 3 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, archived from the original on 2015-09-25.

- 1 2 Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.

- 1 2 Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier.

- ↑ Ralph M. Trüeb. The Difficult Hair Loss Patient: Guide to Successful Management of Alopecia and Related Conditions. Springer, 2015. ISBN 9783319197012 Pg. 95 Archived 2017-11-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Rogers, N; Avram, M (October 2008). "Medical treatments for male and female pattern hair loss". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 59 (4): 547–566. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.001. PMID 18793935.

External links

- Tretinoin AHFS Consumer Medication Information at PubMed Health