Nuristan Province

| Nuristan نورستان | |

|---|---|

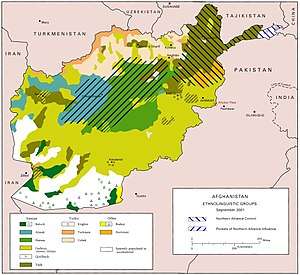

| Province | |

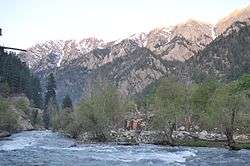

A river in Nuristan province | |

Map of Afghanistan with Nuristan highlighted | |

| Coordinates: 35°15′N 70°45′E / 35.25°N 70.75°ECoordinates: 35°15′N 70°45′E / 35.25°N 70.75°E | |

| Country |

|

| Provincial center | Parun |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Hafiz Abdul Qayyum |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,225.0 km2 (3,561.8 sq mi) |

| Population [1] | |

| • Total | 140,900 |

| • Density | 15/km2 (40/sq mi) |

| Time zone | GMT+4:30 |

| ISO 3166 code | AF-NUR |

| Main languages | Nuristani |

Nuristan, also spelled Nurestan or Nooristan, (Nuristani: نورستان) is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, located in the eastern part of the country. It is divided into seven districts and has a population of about 140,900.[1] Parun serves as the provincial capital.

It was formerly known as Kafiristan (کافرستان, "land of the infidels") until the inhabitants were converted from a grave-revering animist religion[2] that has been described as ancient Hinduism,[3] to Islam in 1895, and thence the region has become known as Nuristan ("land of illumination").[4]

The primary occupations are agriculture, animal husbandry, and day labor. Located on the southern slopes of the Hindu Kush mountains in the northeastern part of the country, Nuristan spans the basins of the Alingar, Pech, Landai Sin, and Kunar rivers. Nuristan is bordered on the south by Laghman and Kunar provinces, on the north by Badakhshan province, on the west by Panjshir province, and on the east by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

History

Early history

The surrounding area fell to Alexander the Great in 330 B.C. It later fell to Chandragupta Maurya. The Mauryas introduced Buddhism to the region, and were attempting to expand their empire to Central Asia until they faced local Greco-Bactrian forces. Seleucus is said to have reached a peace treaty with Chandragupta by giving control of the territory south of the Hindu Kush to the Mauryas upon intermarriage and 500 elephants.

Alexander took these away from the Indo-Aryans and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.'[5]

— Strabo, 64 BCE–24 CE

Some time after, as he was going to war with the generals of Alexander, a wild elephant of great bulk presented itself before him of its own accord, and, as if tamed down to gentleness, took him on its back, and became his guide in the war, and conspicuous in fields of battle. Sandrocottus, having thus acquired a throne, was in possession of India, when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness; who, after making a league with him, and settling his affairs in the east, proceeded to join in the war against Antigonus. As soon as the forces, therefore, of all the confederates were united, a battle was fought, in which Antigonus was slain, and his son Demetrius put to flight.[6]

Having consolidated power in the northwest, Chandragupta pushed east towards the Nanda Empire. Afghanistan's significant ancient tangible and intangible Buddhist heritage is recorded through wide-ranging archeological finds, including religious and artistic remnants. Buddhist doctrines are reported to have reached as far as Balkh even during the life of the Buddha (563 BCE to 483 BCE), as recorded by Xuanzang.

In this context a legend recorded by Xuanzang refers to the first two lay disciples of Buddha, Trapusa and Bhallika responsible for introducing Buddhism in that country. Originally these two were merchants of the kingdom of Balhika, as the name Bhalluka or Bhallika probably suggests the association of one with that country. They had gone to India for trade and had happened to be at Bodhgaya when the Buddha had just attained enlightenment.[7]

Before their conversion to Islam, the Nuristanis or Kafir people practiced a form of ancient Hinduism infused with locally developed accretions.[8] They were called "kafirs" due to their enduring paganism while other regions around them became Muslim. However, the influence from district names in Kafiristan of Katwar or Kator and the ethnic name Kati has also been suggested.[9]

The area extending from modern Nooristan to Kashmir was known as "Peristan", a vast area containing host of "Kafir" cultures and Indo-European languages that became Islamized over a long period. Earlier, it was surrounded by Buddhist areas. The Islamization of the nearby Badakhshan began in the 8th century and Peristan was completely surrounded by Muslim states in the 16th century with Islamization of Baltistan. The Buddhist states temporarily brought literacy and state rule into the region. The decline of Buddhism resulted in it becoming heavily isolated.[10]

There have been varying theories about the origins of Kafirs including the Arab tribe of Quraish, or Gabars of Persia, the Greek soldiers of Alexander as well as the Indians of eastern Afghanistan. George Scott Robertson considered them to be part of the old Indian population of Eastern Afghanistan and stated they fled to the mounatins while refusing to convert to Islam after the Muslim invasion in the 10th century. He added they probably found other races there whom they killed off and enslaved or amalgamated with them.[11]

Oral traditions of some of the Nuristanis place themselves to be at the confluence of Kabul River and Kunar River a millennium ago. These traditions state they were driven off from Kandahar to Kabul to Kapisa to Kama with the Muslim invasion. They identify themselves as late arrivals in Nuristan, being driven by Mahmud of Ghazni who after establishing his empire forced the unsubmissive population to flee.[8]

The name Kator was used by Lagaturman, last king of the Turk Shahi. Apparently due to its usage by the last Turk-Shahi ruler, it was adopted as a title by the ruler of the north-west region of the Indian subcontinent, comprising Chitral and Kafiristan. The title "Shah Kator" was assumed by Chitral's ruler Mohtaram Shah who assumed it upon being impressed by the majesty of the erstwhile pagan rulers of Chitral.[12] The theory of Kators being related to Turki Shahis is based on the information of Jami- ut-Tawarikh and Tarikh-i-Binakiti.[13] The region was also named after its ruling elite. The royal usage may be the origin behind the name of Kator.[14]

The region was invaded by forces of Afghan Amir Abdur Rahman Khan in 1896 and most of the people were converted either by force or did so to avoid the jizya:[15]

In the end, Kafiristan was subdued, most of its residents either by force or for economic reason - namely to avoid the jizya poll tax - were converted to Islam and the region later became known as Nuristan (Land of Light).[15]

— Nile Green, 2016

The region was renamed Nuristan, meaning Land of the enlightened, a reflection of the "enlightening" of the pagan Nuristani by the "light-giving" of Islam.

Nuristan was once thought to have been a region through which Alexander the Great passed with a detachment of his army; thus the folk legend that the Nuristani people are descendants of Alexander (or "his generals").

Abdul Wakil Khan Nuristani is one of the most prominent figures in Nuristan's history. He fought against the British-led Punjabi army and drove them out of the eastern provinces of Afghanistan. He is buried on the same plateau where King Amanullah Khan is buried.

Recent history

Since the creation of Pakistan in 1947, Afghan politicians (particularly Mohammed Daoud Khan) have been focusing on re-annexing Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of what is now Pakistan. This has led to militancy on both sides of the Durand Line.[16] In the meantime, Pakistani politicians have been focusing on connecting what is now Tajikistan with Pakistan. This requires weakening Afghan rule in Nuristan and Badakhshan provinces by secretly funding anti-Afghan rebel forces.

Nuristan was the scene of some of the heaviest guerrilla fightings during the 1980s Soviet–Afghan War. The province was influenced by Mawlawi Afzal's Islamic Revolutionary State of Afghanistan, which was supported by Pakistan nationalists and Saudi Arabia. It dissolved under the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (Taliban rule) in the late 1990s.[17]

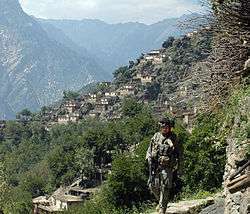

Nuristan is one of the poorest and most remote provinces of Afghanistan. Few NGO's operate in Nuristan because of Taliban insurgency and lack of safe roads. The United States and the Afghan government are jointly working to solve these issues. Some road construction projects were launched linking Nangarej to Mandol and Chapa Dara to Titan Dara.[18] The Afghan government also worked on a direct road route to Laghman province, in order to reduce dependence on the road through restive Kunar province to the rest of Afghanistan. Other road projects were started aimed at improving the primitive road from Kamdesh to Barg-i Matal, and from Nangalam in Kunar province to the provincial center at Parun.

Since Nuristan is a highly ethnically homogeneous province, there are few incidents of inter-ethnic violence. However, there are instances of disputes among inhabitants, some of which continue for decades. Nuristan has suffered from its inaccessibility and lack of infrastructure. The government presence is under-developed, even compared to neighboring provinces. Nuristan's formal educational sector is weak, with few professional teachers. Due to its proximity to Pakistan, many of the inhabitants are actively involved in trade and commerce across the border.

A map from the Afghan Ministry of the Interior produced in 2009 showed the western region of Nuristan to be under "enemy control". There have been numerous conflicts between anti-Afghanistan militants and U.S.-led Afghan security forces. In April 2008 members of the 3rd Special Forces Group led Afghan soldiers from the Commando Brigade into the Shok valley in an unsuccessful attempt to capture warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. In July 2008 approximately 200 Taliban guerrillas attacked a NATO position just south of Nuristan, near the village of Wanat in the Waygal District, killing 9 U.S. soldiers.[19] In the following year, in early October, more than 350 anti-Afghanistan militants backed by members of the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin and other militia groups fought U.S.-led Afghan security forces in the Battle of Kamdesh at Camp Keating in Nuristan. The base was nearly overrun; more than 100 Taliban fighters, eight U.S. soldiers, and seven members of the Afghan security forces were killed during the fighting.[20][21][22][23] Four days after the battle, in early October 2009, U.S. forces withdrew from their four main bases in Nuristan, as part of a plan by General Stanley McChrystal to pull troops out of small outposts and relocate them closer to major towns.[24] The U.S. has pulled out from some areas in the past, but never from all four main bases.[25] A month after the U.S. pullout the Taliban was governing openly in Nuristan.[26] According to The Economist, Nuristan is "a place so tough that NATO abandoned it in 2010 after failing to subdue it."[27]

Politics and governance

The current governor of the province is Hafiz Abdul Qayyum.[29] His predecessor was Jamaluddin Badar, who was sacked and convicted in Kabul for political corruption.[28] The town of Parun serves as the capital of Nuristan province.

All law enforcement activities throughout the province are controlled by the Afghan National Police (ANP). The border with neighboring Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is monitored by the Afghan Border Police (ABP). A provincial police chief is assigned to lead both the ANP and the ABP. The Police Chief represents the Ministry of the Interior in Kabul. The ANP and ABP are backed by the Afghan Armed Forces, including the NATO-led forces.

Healthcare

The percentage of households with clean drinking water increased from 2% in 2005 to 12% in 2011.[30] The percentage of births attended by a skilled birth attendant increased from 1% in 2005 to 22% in 2011.[30]

Education

In 2002 the first gender assessment of women's conditions in Nuristan was completed.[31] The overall literacy rate (6+ years of age) fell from 17.7% in 2005 to 17% in 2011.[30] The overall net enrolment rate (6–13 years of age) increased from 8.7% in 2005 to 45% in 2011.[30]

Demographics

As of 2013, the total population of the province is about 140,900.[1] According to the Naval Postgraduate School, around 99.3% are Nuristanis and 0.6% Gujjars 0.2 Hazara.[32][33]

Approximately 90% of the population speak the following Nuristani languages:[34]

- Askunu language

- Kamkata-viri language

- Vasi-vari language

- Tregami language

- Kalasha-ala language

- Pashayi languages is used by about 15% of the population.[34]

The main Nuristani tribes in the province are:

- Kata or Katta (38%)

- Waigali or Kalasha (30%)

- Ashkun or Wamai (12%)

- Kam or Kom (10%)

- Satra (5%)

- Wasi or Parsoon (4%)

Dari/Pashto are used as second and third languages in the province.

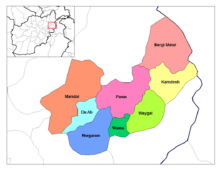

Districts

| District | Center | Population[1] | Area[35] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barg-i Matal | 15,000 | |||

| Du Ab | 7,700 | Established in 2004, formerly part of Nuristan District and Mangol District | ||

| Kamdesh | Kamdesh | 24,500 | ||

| Mandol | 19,200 | Lost territory to Du Ab District in 2004 | ||

| Nurgram | 31,400 | Established in 2004, formerly part of Nuristan District and Wama District | ||

| Parun | Parun | 13,200 | Established in 2004, formerly part of Wama District | |

| Wama | 10,800 | Lost territory to Parun District and Nurgram District in 2004 | ||

| Waygal | 19,100 |

In popular culture

- Nuristan is the subject of the book A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush by the British travel writer Eric Newby.

- Nuristan was the location of three of the missions in Hitman 2: Silent Assassin.

- Rudyard Kipling's short story The Man Who Would Be King and the film inspired by it are set in pre-Islamic Nuristan.

Notable people from the province

- Ahmad Yusuf Nuristani

- Abdul Qadir Nuristani

- Mohammed Nadir Atash

- Issa Nuristani

- Jamaluddin Badr

- Hafiz Abdul Qayoum

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Settled Population of Nooristan province by Civil Division, Urban, Rural and Sex-2012-13" (PDF). Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Central Statistics Organization. Retrieved 2015-07-13.

- ↑ Ansary, Tamim (2014-03-04). Games without Rules: The Often-Interrupted History of Afghanistan. PublicAffairs. ISBN 9781610393195.

“Kafiristan, “Land of the Infidels,” because the people there practiced an animist religion involving elaborate graves decorated with images carved of wood.”

- ↑ Minahan, James B. (10 February 2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 205. ISBN 9781610690188.

Living in the high mountain valleys, the Nuristani retained their ancient culture and their religion, a form of ancient Hinduism with many customs and rituals developed locally. Certain deities were revered only by one tribe or community, but one deity was universally worshipped by all Nuristani as the Creator, the Hindu god Yama Raja, called imr'o or imra by the Nuristani tribes. Around 700 CE, Arab invaders swept through the region now known as Afghanistan, destroying or forcibly converting the population to their new Islamic religion. Refugees from the invaders fled into the higher valleys to escape the onslaught. In their mountain strongholds, the Nuristani escaped conversion to Islam and retained their ancient religion and culture. The surrounding Muslim peoples used the name Kafir, meaning "unbeliever" or "infidel," to describe the independent Nuristani tribes and called their highland homeland Kafiristan.

- ↑ Klimberg, Max (October 1, 2004). "NURISTAN". Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). United States: Columbia University.

- ↑ Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul - The Name". American International School of Kabul. Archived from the original on 2010-08-30. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ↑ Historiarum Philippicarum libri XLIV, XV.4.19

- ↑ Puri, Baij Nath (1987). Buddhism in central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 352. ISBN 81-208-0372-8. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- 1 2 Richard F. Strand (31 December 2005). "Richard Strand's Nuristân Site: Peoples and Languages of Nuristan". nuristan.info.

- ↑ C. E. Bosworth; E. Van Donzel; Bernard Lewis; Charles Pellat (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume IV. Brill. p. 409.

- ↑ Alberto M. Cacopardo (2016). "Fence of Peristan - The Islamization of the "Kafirs" and Their Domestication". Archivio per l'Antropologia e la Etnologia. Società Italiana di Antropologia e Etnologia: 69, 77.

- ↑ Ludwig W. Adamec (1985). Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Volume 6. Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt Graz. p. 348.

- ↑ Dr. Hussain Khan. "The Genesis of the Royal Title". Journal of Central Asia. Centre for the Study of the Civilizations of Central Asia, Quaid-i-Azam University. 14: 111, 112.

- ↑ Deena Bandhu Pandey (1973). The Shahis of Afghanistan and the Punjab. Historical Research Institute; Oriental Publishers. p. 65.

- ↑ Dr. Hussain Khan. "The Genesis of the Royal Title". Journal of Central Asia. Centre for the Study of the Civilizations of Central Asia, Quaid-i-Azam University. 14: 114.

- 1 2 Nile Green. Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban. University of California Press. pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Bowersox, Gary W. (2004). The Gem Hunter: The Adventures of an American in Afghanistan. United States: GeoVision, Inc.,. p. 100. ISBN 0-9747-3231-1. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

To launch this plan, Bhutto recruited and trained a group of Afghans in the Bala-Hesar of Peshawar, in Pakistan's North-west Frontier Province. Among these young men were Massoud, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, and other members of Jawanan-e Musulman. Massoud's mission to Bhutto was to create unrest in northern Afghanistan. It served Massoud's interests, which were apparently opposition to the Soviets and independence for Afghanistan. Later, after Massoud and Hekmatyar had a terrible falling-out over Massoud's opposition to terrorist tactics and methods, Massoud overthrew from Jawanan-e Musulman. He joined Rabani's newly created Afghan political party, Jamiat-i-Islami, in exile in Pakistan.

- ↑ Daan Van Der Schriek, ed. (May 26, 2005). "Nuristan: Insurgent Hideout in Afghanistan, Terrorism Monitor, Volume 3, Issue 10". Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ↑ "Nuristan governor, contractor, and Afghanistan engineer district sign partnership agreement". Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved 2006-06-28. , Headquarters US Central Command, News Release, June 13, 2006

- ↑ "Taliban fighters storm US base". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Taliban govern openly in Nuristan, Bill Roggio, Long War Journal, 2009-11-12

- ↑ Taliban Claim to Seize American Arms, Robert Mackey, New York Times, 2009-11-12

- ↑ Eight U.S. Troops Die in Attack on Afghan Outpost, Joshua Partow, Washington Post, 2009-10-04

- ↑ Heavy US losses in Afghan battle, Martin Patience, BBC News, Kabul, 4 October 2009

- ↑ Kamdesh ambush played out like Wanat battle, Matthew Cox and Michelle Tan, Army Times, November 3, 2009

- ↑ "South Asia news, business and economy from India and Pakistan". Asia Times Online. 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ↑ Taliban govern openly in Nuristan, Bill Roggio, Long War Journal, 2009-11-12

- ↑ "Pakistan's border badlands: Double games". The Economist. Jul 12, 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- 1 2 Zarghona Salehi, ed. (September 26, 2012). "Governor among 3 ex-Nuristan officials jailed". Pajhwok Afghan News. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ↑ Mahbob Shah Mahbob, ed. (April 22, 2014). "Nuristan's development completely neglected: Governor". Pajhwok Afghan News. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- 1 2 3 4 Archive, Civil Military Fusion Centre Archived 2014-05-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Wazhma Frogh". inclusivesecurity.org.

- ↑ "Nuristan Province" (PDF). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies. Naval Postgraduate School. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ↑ Nuristan Tribal Map on nps.edu

- 1 2 Nuristan provincial profile profile compiled by the National Area-Based Development Programme (NABDP) of the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD)

- ↑ Afghanistan Geographic & Thematic Layers

Further reading

- Dupree, Nancy Hatch (1977): An Historical Guide to Afghanistan. 1st Edition: 1970. 2nd Edition. Revised and Enlarged. Afghan Tourist Organization. LINK

- Richard F. Strand. (1997–present) Richard Strand's Nuristan Site LINK. The most accurate and comprehensive source on Nuristan, by the world's leading scholar on the languages and ethnic groups of Nuristan.

- M. Klimburg. NURISTAN in Encyclopedia Iranica. LINK

- Edelberg, Lennart (1984) "Nuristani Buildings" Jutland Archaeological Society Publications, Vol. 18, 1984.

- Edelberg, Lennart & Schuyler Jones (1979) "Nuristan" Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria

- Jones, Schuyler (1992) "Afghanistan" Vol. 135 of the World Bibliographical Series, Clio Press, Oxford.

- Jones, Schuyler (1974) "Men of Influence in Nuristan: A Study of Social Control & Dispute Settlement in Waigal Valley, Afghanistan." Seminar Press, London & New York.

- Wilber, Donald N. (1968)Annotated Bibliography of Afghanistan. Human Relations Area Files, New Haven, Conn.

- Jones, Schuyler (1966) An Annotated Bibliography of Nuristan (Kafiristan) and the Kalash Kafirs of Chitral, Part One. Royal Danish Academy of Sciences & Letters, Vol. 41, No. 3.

- Kukhtina, Tatiyana I. (1965) Bibliografiya Afghanistana: Literatuyra na russkom yazyka. Nauka, Moscow.

- Akram, Mohammed (1947) Bibliographie de l'Afghanistan, I, ouvrages parus hors de l'Afghanistan. Centre de Documentation Universitaire, Paris.

- Robertson, Sir George S. (1900) The Kafirs of Hindu-Kush. LINK

External sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuristan Province. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Nuristan. |

- Nuristan Province by the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS)

- Nuristan Province by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW)