Alchon Huns

Alchon Huns | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 380–560 | |||||||||||||||||||

The bull/ lunar tamga of the Alchon

| |||||||||||||||||||

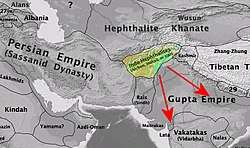

Alchon territories and campaigns into Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, c. 500 CE. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kapisa | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Brahmi and Bactrian (written) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism, Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Nomadic empire | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tegin | |||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 380 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 560 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Drachm | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||||||||||

The Alchon Huns, also known as the Alchono, Alxon, Alkhon, Alkhan, Alakhana and Walxon, were a nomadic people who established states in Central Asia and South Asia during the 4th and 6th centuries CE. They were first mentioned as being located in Paropamisus, and later expanded south-east, into the Punjab and central India, as far as Eran and Kausambi. The Alchon invasion of the Indian subcontinent contributed to the fall of the Gupta Empire.

The invasion of India by the Huna peoples follows invasions of the subcontinent in the preceding centuries by the Yavana (Indo-Greeks), the Saka (Indo-Scythians), the Palava (Indo-Parthians), and the Kushana (Yuezhi). The Alchon Empire was the third of four major Huna states established in Central and South Asia. The Alchon were preceded by the Kidarites and the Hephthalites, and succeeded by the Nezak Huns. The names of the Alchon kings are known from their extensive coinage, Buddhist accounts, and a number of commemorative inscriptions throughout the Indian subcontinent.

Name

To contemporaneous observers in India, the Alchon were one of the Hūṇa peoples (or Hunas),[1] whose origins are controversial. A seal from Kausambi associated with Toramana, bears the title Hūnarāja ("Huna King").[2]

The Hunas appear to have been the peoples known in contemporaneous Iranian sources as Xwn, Xiyon and similar names, which were later Romanised as Xionites or Chionites. The Hunas are often linked to the Huns that invaded Europe from Central Asia during the same period. Consequently, the word Hun has three slightly different meanings, depending on the context in which it is used: 1) the Huns of Europe; 2) groups associated with the Huna people who invaded northern India; 3) a vague term for Hun-like people. The Alchon have also been labelled "Huns", with essentially the second meaning, as well as elements of the third. [6][7]

The name "Alchon" generally given to them comes from the Bactrian legend of their early coinage, where they simply imitated Sassanian coins to which they added the name "alchono" (αλχονο, also αλχοννο)[8] in Bactrian script (a slight adaptation of the Greek script) and the tamgha symbol of their clan.[9][10][3][11] Several original coins such as those of Khingila also bear the mention "alchono" together with the Tamgha symbol.[3] Philologically, "alchono" (αλχονο) may be a combination of al- for Aryan and -xono for Huns, although this remains hypothetical.[4] Another ethymology could be al-, Turkish for scarlet, and -xono for Huns, meaning "Red Huns", red being a symbol of the south among steppe nomads.[12]

History

Invasion of Bactria

Early confrontations between the Sasanian Empire of Shapur II with the nomadic hordes from Central Asia called the "Chionites" were described by Ammianus Marcellinus: he reports that in 356 CE, Shapur II was taking his winter quarters on his eastern borders, "repelling the hostilities of the bordering tribes" of the Chionites and the Euseni ("Euseni" is usually amended to "Cuseni", meaning the Kushans),[15][16] finally making a treaty of alliance with the Chionites and the Gelani, "the most warlike and indefatigable of all tribes", in 358 CE.[17] After concluding this alliance, the Chionites (probably of the Kidarites tribe)[18] under their King Grumbates accompanied Shapur II in the war against the Romans, especially at the Siege of Amida in 359 CE. Victories of the Xionites during their campaigns in the Eastern Caspian lands were also witnesses and described by Ammianus Marcellinus.[19]

Finally around 370 CE, still during the reign of Shapur II, the Sasanian Empire and the Kushano-Sasanians completely lost the control of Bactria to these invaders from Central Asia, first the Kidarites, then the Hephthalites and the Alchon Huns, who would follow up with the invasion of India.[20] The Alchon Huns emerged in Kapisa around 380, taking over Kabulistan from the Sassanian Persians, at the same time the Kidarites (Red Huns) ruled in Bactria and Ghandara. They are said to have taken control of Kabul in 388.[1]

The Alchon Huns initially issued anonymous coins based on Sasanian designs.[13] Several types of these coins are known, usually minted in Bactria, using Sasanian coinage designs with busts imitating Sasanian kings Shapur II (r.309 to 379 CE) and Shapur III (r.383 to 388 CE), adding the Alchon Tamgha and the name "Alchono" in Bactrian script (a slight adaptation of the Greek script which had been introduced in the region by the Greco-Bactrians in the 3rd century BCE) on the obverse, and with attendants to a fire altar, a standard Sasanian design, on the reverse.[21][22]

Gandhara

Around 430 King Khingila, the most notable Alchon ruler, and the first one to be named and represented on his coins, emerged and took control of the routes across the Hindu Kush from the Kidarites.[1] As the Alchons took control, diplomatic missions were established in 457 with China.[23]:162 In 460, the Alchons conquered Taxila. Between 460 and 470 CE, as they took over Gandhara and the Punjab, they apparently undertook the mass destruction of Buddhist monasteries and stupas at Taxila, a high center of learning, which never recovered from the destruction. It is thought that the Kanishka stupa, one of the most famous and tallest buildings in antiquity, was destroyed by them during their invasion of the area in the 460s CE.[24]

The rest of the 5th century marks a period of territorial expansion and eponymous kings (Tegins), several of which appear to have overlapped and ruled jointly.[25][Note 1]

First Hunnic War: Central India

In the First Hunnic War (496–515),[26] the Alchon reached their maximum territorial extent, with King Toramana pushing deep into Indian territory, reaching Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh in Central India, and ultimately contributing to the downfall of the Gupta Empire.[23]:162 To the south, the Sanjeli inscriptions indicate that Toramana penetrated at least as far as northern Gujarat, and possibly to the port of Bharukaccha.[27] To the east, far into Central India, the city of Kausambi, where seals with Toramana's name were found, was probably sacked by the Alkhons in 497–500, before they moved to occupy Malwa.[26][28][29]:70[30] In particular, it is thought that the monastery of Ghoshitarama in Kausambi was destroyed by Toramana, as several of his seals were found there, one of them bearing the name Toramana impressed over the official seal of the monastery, and the other bearing the title Hūnarāja, together with debris and arrowheads.[2] Another seal, this time by Mihirakula, is reported from Kausambi.[2] These territories may have been taken from Gupta Emperor Budhagupta.[29]:79 Alternatively, they may have been captured during the rule of his successor Narasimhagupta.[31]

First Battle of Eran (510 CE)

A decisive battle occurred in Malwa, where a local Gupta ruler, probably a governor, named Bhanugupta was in charge. In the Bhanugupta Eran inscription, this local ruler reports that his army participated in a great battle in 510 CE at Eran, where it suffered severe casualties.[31] Bhanugupta was probably vanquished by Toramana at this battle, so that the western Gupta province of Malwa fell into the hands of the Hunas.[31]

According to a 6th-century CE Buddhist work, the Manjusri-mula-kalpa, Bhanugupta lost Malwa to the "Shudra" Toramana, who continued his conquest to Magadha, forcing Narasimhagupta Baladitya to make a retreat to Bengal. Toramana "possessed of great prowess and armies" then conquered the city of Tirtha in the Gauda country (modern Bengal).[32][Note 2] Toramana is said to have crowned a new king in Benares, named Prakataditya, who is also presented as a son of Narasimha Gupta.[33][31]

Having conquered the territory of Malwa from the Guptas, Toramana was mentioned in a famous inscription in Eran, confirming his rule on the region.[31] The Eran boar inscription of Toramana (in Eran, Malwa, 540 km south of New Delhi, state of Madhya Pradesh) of his first regnal year indicates that eastern Malwa was included in his dominion. The inscription is written under the neck of the boar, in 8 lines of Sanskrit in the Brahmi script. The first line of the inscription, in which Toramana is introduced as Mahararajadhidaja (The Great King of Kings),[29]:79 reads:

"In year one of the reign of the King of Kings Sri-Toramana, who rules the world with splendor and radiance..."

On his gold coins minted in India in the style of the Gupta Emperors, Toramana presented himself confidently as:

""Avanipati Torama(no) vijitya vasudham divam jayati"

"The lord of the Earth, Toramana, having conquered the Earth, wins Heaven"

Defeat (515 CE)

Toramana was finally defeated by local Indian rulers. The local ruler Bhanugupta is sometimes credited with vanquishing Toramana, as his 510 CE inscription in Eran, recording his participation in "a great battle", is vague enough to allow for such an interpretation. The "great battle" in which Bhanagupta participated is not detailed, and it is impossible to know what it was, or which way it ended, and interpretations vary.[37][38][39] Mookerji and others consider, in view of the inscription as well as the Manjusri-mula-kalpa, that Bhanugupta was, on the contrary, vanquished by Toramana at the 510 CE Eran battle, so that the western Gupta province of Malwa fell into the hands of the Hunas at that point,[31][33] so that Toramana could be mentioned in the Eran boar inscription, as the ruler of the region.[31]

Toramana was finally vanquished with certainty by an Indian ruler of the Aulikara dynasty of Malwa, after nearly 20 years in India. According to the Rīsthal stone-slab inscription, discovered in 1983, King Prakashadharma defeated Toramana in 515 CE.[26][27][40] The First Hunnic War thus ended with a Hunnic defeat, and Hunnic troops apparently retreated to the area of Punjab.[26] The Manjusri-mula-kalpa simply states that Toramana died in Benares as he was returning westward from his battles with Narasimhagupta.[31]

Second Hunnic War: to Malwa and retreat

The Second Hunnic War started in 520, when the Alchon king Mihirakula, son of Toramana, is recorded in his military encampment on the borders of the Jhelum by Chinese monk Song Yun.[26] At the head of the Alchon, Mihirakula is then recorded in Gwalior, Central India as "Lord of the Earth" in the Gwalior inscription of Mihirakula.[26] According to some accounts, Mihirakula invaded India as far as the Gupta capital Pataliputra, which was sacked and left in ruins.[41][29]:64

Finally however, Mihirakula was defeated in 528 by an alliance of Indian principalities led by Yasodharman, the Aulikara king of Malwa, in the battle of Sondani in Central India, which resulted in the loss of Alchon possessions in the Punjab and north India by 542. The Sondani inscription in Sondani, near Mandsaur, records the submission by force of the Hunas, and claims that Yasodharman had rescued the earth from rude and cruel kings,[42][Note 3] and that he "had bent the head of Mihirakula".[26] In a part of the Sondani inscription Yasodharman thus praises himself for having defeated king Mihirakula:[34]

He (Yasodharman) to whose two feet respect was paid, with complimentary presents of the flowers from the lock of hair on the top of (his) head, by even that (famous) king Mihirakula, whose forehead was pained through being bent low down by the strength of (his) arm in (the act of compelling) obeisance

The Gupta Empire emperor Narasimhagupta is also credited in helping repulse Mihirakula, after the latter had conquered most of India, according to the reports of Chinese monk Xuanzang.[44][45] In a fanciful account, Xuanzang, who wrote a century later in 630 CE, reported that Mihirakula had conquered all India except for an island where the king of Magadha named Baladitya (who could be Gupta ruler Narasimhagupta Baladitya) took refuge, but that was finally captured by the Indian king. He later spared Mihirakula's life on the intercession of his mother, as she perceived the Hun ruler "as a man of remarkable beauty and vast wisdom".[45] Mihirakula is then said to have returned to Kashmir to retake the throne.[46][23]:168 This ended the Second Hunnic War in c. 534, after an occupation which lasted nearly 15 years.[26]

Retreat to Kabulistan

Around the middle of the 6th century CE, the Alchons withdrew to Kashmir and, pulling back from Punjab and Gandhara, moved west across the Khyber pass where they resettled in Kabulistan. There, their coinage suggests that they merged with the Nezak – as coins in Nezak style now bear the Alchon tamga mark.[47][34]

During the 7th century, continued military encounters are reported between the Hunas and the northern Indian states which followed the disappearance of the Gupta Empire. For example, Prabhakaravardhana, the Vardhana dynasty king of Thanesar in northern India and father of Harsha, is reported to have been "A lion to the Huna deer, a burning fever to the king of the Indus land".[48]:253

The Alchons in India declined rapidly around the same time that the Hephthalites, a related group to the north, were defeated by an alliance between the Sassanians and the Western Turkic Kaghanate.[49]:187 Eventually, the Nezak-Alchons were replaced by the Turk shahi dynasty.[49]:187

Religion and ethics

The four Alchon kings Khingila, Toramana, Javukha, and Mehama are mentioned as donors to a Buddhist stupa in the Talagan copper scroll inscription dated to 492 or 493 CE, that is, at a time before the Hunnic wars in India started. This corresponds to a time when the Alchons had recently taken control of Taxila (around 460 CE), at the center of the Buddhist regions of northwestern India.[50]

Persecution of Buddhism

Later however, the attitude of the Alchons towards Buddhism is reported to have been negative. Mihirakula in particular is remembered by Buddhist sources to have been a "terrible persecutor of their religion" in Gandhara in northern Pakistan.[51] During his reign, over a thousand Buddhist monasteries throughout Gandhara are said to have been destroyed.[52] In particular the Chinese monk Xuanzang, writing in 630 CE, explained that Mihirakula ordered the destruction of Buddhism and the expulsion of monks.[23]:162 Indeed, the Buddhist art of Gandhara, in particular Greco-Buddhist art, becomes essentially extinct around that period. When Xuanzang visited northwestern Indian in c. 630 CE, he reported that Buddhism had drastically declined, and that most of the monasteries were deserted and left in ruins.[53]

Although the Guptas were traditionally a Brahmanical dynasty,[54] around the period of the invasions of the Alchon, the Gupta rulers had apparently been favouring Buddhism. Narasimhagupta Baladitya, Mihirakula's supposed nemesis, was, according to contemporary writer Paramartha, brought up under the influence of the Mahayanist philosopher, Vasubandhu.[54] He built a sangharama at Nalanda and a 300 ft (91 m) high vihara with a Buddha statue within which, according to Xuanzang, resembled the "great Vihara built under the Bodhi tree". According to the Manjushrimulakalpa (c. 800 CE), king Narasimhsagupta became a Buddhist monk, and left the world through meditation (Dhyana).[54] The Chinese monk Xuanzang also noted that Narasimhagupta Baladitya's son, Vajra, who commissioned a sangharama as well, "possessed a heart firm in faith".[55]:45[56]:330

The 12th century Kashmiri historian Kalhana also painted a dreary picture of Mihirakula's cruelty, as well as his persecution of the Buddhist faith:

"In him, the northern region brought forth, as it were, another god of death, bent in rivalry to surpass... Yama (the god of death residing in the southern regions). People knew of his approach by noticing the vultures, crows and other birds flying ahead eager to feed on those who were being slain within his army's reach. The royal Vetala (demon) was day and night surrounded by thousands of murdered human beings, even in his pleasure houses. This terrible enemy of mankind had no pity for children, no compassion for women, no respect for the aged"

Shivaism and Sun cult

The Alchons are generally described as sun worshipers, a traditional cult of steppe nomads, due to the appearance of sun symbols on some of their coins, combined to the probable influence they received from the cult of Surya in India.[57] Mihirirakula is also said to have been an ardent worshiper of Shiva,[58][59] although he may have been selectively attracted by the destructive powers of the Indian deity.[45]

Consequences on India

The Alchon invasions, although only spanning a few decades, had long term effects on India, and in a sense brought an end to the middle kingdoms of India.[45] Soon after the invasions, the Gupta Empire, already weakened by these invasions and the rise of local rulers, ended as well.[48]:221 Following the invasions, northern India was left in disarray, with numerous smaller Indian powers emerging after the crumbling of the Guptas.[60]

The Huna invasions are said to have seriously damaged India's trade with Europe and Central Asia,[45] in particular, Indo-Roman trade relations, which the Gupta Empire had greatly benefited from. The Guptas had been exporting numerous luxury products such as silk, leather goods, fur, iron products, ivory, pearl and pepper from centers such as Nasik, Paithan, Pataliputra and Benares. The Huna invasion probably disrupted these trade relations and the tax revenues that came with them.[61] Furthermore, Indian urban culture was left in decline, and Buddhism, gravely weakened by the destruction of monasteries and the killing of monks, started to collapse.[45] Great centers of learning were destroyed, such as the city of Taxila, bringing cultural regression.[45]

During their rule of 60 years, the Alchons are said to have altered the hierarchy of ruling families and the Indian caste system. For example, the Hunas are often said to have become the precursors of the Rajputs.[45] On the artistic side however, the Alchon Huns may have played a role, just like the Western Satraps centuries before them, in helping spread the art of Gandhara to the western Deccan region.[62]

Sources

Ancient sources refer to the Alchons and associated groups ambiguously with various names, such as Huna in Indian texts, and Xionites in Greek texts. Xuanzang chronicled some of the later history of the Alchons.[44]

Modern archeology has provided valuable insights into the history of the Alchons. The most significant cataloguing of the Alchon dynasty came in 1967 with Robert Göbl's analysis of the coinage of the "Iranian Huns".[63] This work documented the names of a partial chronology of Alchon kings, beginning with Khingila. In 2012, the Kunsthistorisches Museum completed a reanalysis of previous finds together with a large number of new coins that appeared on the antiquities market during the Second Afghan Civil War, redefining the timeline and narrative of the Alchons and related peoples.[49]

Talagan copper scroll

| Alchon rulers (400–600 CE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A significant contribution to our understanding of Alchon history came in 2006 when Gudrun Melzer and Lore Sander published their finding of the "Talagan copper scroll", also known as the "Schøyen Copper Scroll", dated to 492 or 493, that mentions the four Alchon kings Khingila, Toramana, Javukha, and Mehama (who was reigning at the time) as donors to a Buddhist reliquary stupa.[64][Note 4][Note 5]

Tegins

The rulers of the Alchons practiced skull deformation, as evidenced from their coins, a practice shared with the Huns that migrated into Europe. The names of the first Alchon rulers do not survive. Starting from 430 CE, names of Alchon kings, assuming the title "Tegin", survive on coins[63] and religious inscriptions:[64]

- anonymous kings (400 - 430 CE)

- Khingila (c. 430 – 490 CE)

- Javukha/Zabocho (c. mid 5th – early 6th CE)

- Mehama (c. 461 – 493 CE)

- Lakhana Udayaditya (c. 490's CE)

- Aduman

- Toramana (c. 490 – 515 CE)

- Mihirakula (c. 515 – 540 CE)

- Toramana II (c. 530 – 570 CE)

- Narana/Narendra (c. 570 – 600 CE)

Coinage

- Early Bactrian coinage based on Sasanian designs

The earliest Alchon Hun coins were based on Sasanian designs, often with the simple addition of the Alchon tamgha and a mention of "Alchon" or "Alkhan".[13] Various coins minted in Bactria and based on a Sasanian designs are known, often with busts imitating Sasanian kings Shapur II (r.309 to 379 CE) and Shapur III (r.383 to 388 CE), with attendants to a fire altar on the reverse.[66][67] It is thought that the Sasanids lost control of Bactria to the Kidarites during the reign of Shapur II circa 370 CE, followed by the Hephthalites, and subsequently by the Alchon.[68]

- Later original coinage

Soon, however, the coinage of the Alchon becomes original and differs from predecessors in that it is devoid of Iranian (Sasanian) symbolism.[1] The rulers are depicted with elongated skulls, apparently a result of artificial cranial deformation.[1]

After their invasion of India the coins of the Alchon were numerous and varied, as they issued copper, silver and gold coins, sometimes roughly following the Gupta pattern. The Alchon empire in India must have been quite significant and rich, with the ability to issue a significant volume of gold coins.[69]

Alchon Tamgha symbol on a coin of Khingila.

Alchon Tamgha symbol on a coin of Khingila. Khingila with the word "Alchono" in Bactrian script (αλχονο) and the Tamgha symbol on his coins.[70][71]

Khingila with the word "Alchono" in Bactrian script (αλχονο) and the Tamgha symbol on his coins.[70][71]

- Silver drachm of Khingila (mature portrait), legend: "Khiggilo Alchono".[Note 7]

Silver drachm of Javukha, mid-late 5th century.

Silver drachm of Javukha, mid-late 5th century. Silver drachm of Mehama legend: “ṣāhi mehama", mid-late 5th century.

Silver drachm of Mehama legend: “ṣāhi mehama", mid-late 5th century. Silver drachm of Lakhana, late 5th-early 6th centuries.

Silver drachm of Lakhana, late 5th-early 6th centuries. Gold dinar of Adomano, Kushano-Sasanian style, mid-late 5th century.

Gold dinar of Adomano, Kushano-Sasanian style, mid-late 5th century. Silver drachm of Mihirakula, early-mid 6th century.

Silver drachm of Mihirakula, early-mid 6th century. Bronze drachm of Toramana II wearing trident crown, late-phase Gandharan style. mid 6th century.

Bronze drachm of Toramana II wearing trident crown, late-phase Gandharan style. mid 6th century. Silver stater of Toramana II, Kashmir style, mid-late 6th century.

Silver stater of Toramana II, Kashmir style, mid-late 6th century. Bronze drachm of Narana-Narenda (possibly Toramana II) wearing trident crown, late 6th century.

Bronze drachm of Narana-Narenda (possibly Toramana II) wearing trident crown, late 6th century. Khingila as a young king, without headdress. Artificial cranial deformation clearly visible.

Khingila as a young king, without headdress. Artificial cranial deformation clearly visible.- Vishnu Nicolo Seal representing Vishnu with a worshipper (probably Mihirakula), 4th–6th century CE. The inscription in cursive Bactrian reads: "Mihira, Vishnu and Shiva". British Museum.

Notes

- ↑ "Here, for the first time, the names of Hepthalite (Alchon) kings are given, some of them otherwise known only from coins. Another important fact is that it dates all these kings in the same time." from Aydogdy Kurbanov (2010). The hephthalites: archaeological and historical analysis. Berlin: Free University of Berlin. p. 120. OCLC 863884689. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ "After the successful conclusion of the Eran episode, the conquering Hunas ultimately burst out of Eastern Malwa and swooped down upon the very heart of the Gupta empire. The eastern countries were overrun and the city of the Gaudas was occupied. The Manjusrimulakalpa gives a scintillating account of this phase of Toramana’s conquest. It says that after Bhanugupta's defeat and discomfiture, Toramana led the Hunas against Magadha and obliged Baladitya (Narasimha-gupta Baladitya, the reigning Gupta monarch) to retire to Bengal. This great monarch (Toramana), Sudra by caste and possessed of great prowess and armies took hold of that position (bank of the Ganges) and commanded the country round about. That powerful king then invested the town called Tirtha in the Gauda country." in Upendra Thakur (1967). The Hūṇas in India. 58. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office. p. 122. OCLC 551489665.

- ↑ "The earth betook itself (for succour), when it was afflicted by kings of the present age, who manifested pride; who were cruel through want of proper training; who,from delusion, transgressed the path of good conduct; (and) who were destitute of virtuous delights " from "Sondhni pillars: where Punjabis met with their Waterloo 1500 years ago". Punjab Monitor. Amritsar: Bhai Nand Lal Foundation. 27 April 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ "Together with the great sahi Khingila, together with the god-king Toramana, together with the mistress of a great monastery Sasa, together with the great sahi Mehama, together with Sadavikha, together with the great king Javukha, the son of Sadavikha, during the reign of Mehama."from Gudrun Melzer; Lore Sander (2000). Jens Braarvig, ed. A Copper Scroll Inscription from the Time of the Alchon Huns. Buddhist manuscripts. 3. Oslo: Hermes Pub. pp. 251–278. ISBN 9788280340061.

- ↑ For an image of the copper scroll: Coin Cabinet of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna Showcase 8

- ↑ For equivalent coin, see CNG Coins

- ↑ This coin is in the collection of the British Museum. For equivalent coin, see CNG Coins

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Michael Maas (29 September 2014). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-316-06085-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Gupta, Parmanand (1989). Geography from Ancient Indian Coins & Seals. Concept Publishing Company. p. 174-175. ISBN 9788170222484.

- 1 2 3

- 1 2 Alemany, Agustí (2000). Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation. BRILL. p. 346. ISBN 9004114424.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani; B. A. Litvinsky; Unesco (1 January 1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. Paris: UNESCO. p. 119. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ↑ Hyun Jin Kim (19 November 2015). The Huns. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-317-34090-4.

- ↑ Alemany, Agustí (2000). Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation. BRILL. p. 345. ISBN 9004114424.

- 1 2 3 Braarvig, Jens (2000). Buddhist Manuscripts (Vol.3 ed.). Hermes Pub. p. 257. ISBN 9788280340061.

- ↑ For one of these coins:

- ↑ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 199. ISBN 9781474400312.

- ↑ Kim, Hyun Jin (2015). The Huns. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 9781317340904.

- 1 2 3 4 Tandon, Pankaj (2013). "Notes on the Evolution of Alchon Coins" (PDF). Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society (216): 24–34. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ Scheers, Simone; Quaegebeur, Jan (1982). Studia Paulo Naster Oblata: Orientalia antiqua (in French). Peeters Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 9789070192105.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History. London: Bohn (1862) XVI-IX

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History. London: Bohn (1862) XVII-V

- ↑ Cosmo, Nicola Di; Maas, Michael (2018). Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750. Cambridge University Press. p. 698. ISBN 9781108547000.

- ↑ History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, Unesco p.38 sq

- ↑ Neelis, Jason (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. BRILL. p. 159. ISBN 9004181598.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ Rienjang, Wannaporn; Stewart, Peter (2018). Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd-24th March, 2017. Archaeopress. p. 23. ISBN 9781784918552.

- 1 2 3 4 Jason Neelis (19 November 2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 90-04-18159-8.

- ↑ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. ISBN 9780984404308. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Aydogdy Kurbanov (2010). The hephthalites: archaeological and historical analysis. Berlin: Free University of Berlin. p. 120. OCLC 863884689. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hans T. Bakker (26 November 2016). Monuments of Hope, Gloom, and Glory in the Age of the Hunnic Wars: 50 years that changed India (484 - 534) (Speech). 24th Gonda Lecture. Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- 1 2 Hans Bakker (16 July 2014). The World of the Skandapurāṇa. Leiden: BRILL. p. 34. ISBN 978-90-04-27714-4.

- ↑ V.K. Agnihotri, ed. (2010). Indian History (26 ed.). New Delhi: Allied Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 978-81-8424-568-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha, Cir. 450-1200 A.D. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. GGKEY:KR1EJ2EGCTJ.

- ↑ Parmanand Gupta (1989). Geography from Ancient Indian Coins & Seals. New DELHI: Concept Publishing Company. p. 175. ISBN 978-81-7022-248-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Radhakumud Mookerji (1997). The Gupta Empire (5th ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 120. ISBN 978-81-208-0440-1.

- ↑ Upendra Thakur (1967). The Hūṇas in India. 58. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office. p. 122. OCLC 551489665.

- 1 2 Raj Kumar (2010). Early history of Jammu region. 2. Delhi: Gyan Publishing House. p. 538. ISBN 978-81-7835-770-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Coin Cabinet of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

- 1 2 CNG Coins

- 1 2 The Identity of Prakasaditya by Pankaj Tandon, Boston University

- ↑ Om Prakash Misra (2003). Archaeological Excavations in Central India: Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-7099-874-7.

- ↑ S. B. Bhattacherje (1 May 2009). Encyclopaedia of Indian Events & Dates. A15. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-207-4074-7.

- ↑ R.K. Pruthi (2004). The Classical Age. New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House. p. 262. ISBN 978-81-7141-876-3.

- ↑ N. K. Ojha (2001). The Aulikaras of Central India: history and inscriptions. Chandigarh: Arun Pub. House. pp. 48–50. ISBN 978-81-85212-78-4.

- ↑ Tej Ram Sharma (1978). Personal and Geographical Names in the Gupta Inscriptions. Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. p. 232. OCLC 923058151. GGKEY:RYD56P78DL9.

- 1 2 "Sondhni pillars: where Punjabis met with their Waterloo 1500 years ago". Punjab Monitor. Amritsar: Bhai Nand Lal Foundation. 27 April 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ John Faithfull Fleet (1888). John Faithfull Fleet, ed. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum: Inscriptions of the early Gupta kings and their successors. 3. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Print. pp. 147–148. OCLC 69001098. Archived from the original on 2015-07-01.

- 1 2 Kailash Chand Jain (31 December 1972). Malwa Through The Ages. Dewlhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 249. ISBN 978-81-208-0824-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Abraham Eraly (2011). The First Spring: The Golden Age of India. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-670-08478-4.

- ↑ Ashvini Agrawal (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 245. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

- 1 2 CNG Coins

- 1 2 Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Delhi: New Age International. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- 1 2 3 Klaus Vondrovec (2014). Coinage of the Iranian Huns and Their Successors from Bactria to Gandhara (4th to 8th Century CE). Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 978-3-7001-7695-4.

- ↑ de la Vaissiere, Etienne (2007). "A Note on the Schøyen Copper Scroll: Bactrian or Indian?" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 21: 127. JSTOR i24047314. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ René Grousset (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- ↑ Behrendt, Kurt A. (2004). Handbuch der Orientalistik. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9789004135956.

- ↑ Ann Heirman; Stephan Peter Bumbacher (11 May 2007). The Spread of Buddhism. Leiden: BRILL. p. 60. ISBN 978-90-474-2006-4.

- 1 2 3 Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Delhi: Pearson Education India. p. 521. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ↑ Sankalia, Hasmukhlal Dhirajlal (1934). The University of Nālandā. Madras: B. G. Paul & co. OCLC 988183829.

- ↑ Sukumar Dutt (1988) [First published in 1962]. Buddhist Monks And Monasteries of India: Their History And Contribution To Indian Culture. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. ISBN 81-208-0498-8.

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton (15 January 2014). Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History: 5,000 Years of Religious History. 1. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 455. ISBN 978-1-61069-026-3.

- ↑ Krishna Chandra Sagar (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. New Delhi: Northern Book Centre. p. 270. ISBN 978-81-7211-028-4.

- ↑ Lal Mani Joshi (1987). Studies in the Buddhistic Culture of India During the Seventh and Eighth Centuries A.D. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 320. ISBN 978-81-208-0281-0.

- ↑ A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set). New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. 1 December 2003. p. 174. ISBN 978-81-207-2503-4.

- ↑ Singh (2010). Longman History & Civics ICSE 9. New Delhi: Pearson Education India. p. 81. ISBN 978-81-317-2041-7.

- ↑ Brancaccio, Pia (2010). The Buddhist Caves at Aurangabad: Transformations in Art and Religion. Leiden: BRILL. p. 107. ISBN 9004185259.

- 1 2 Robert Göbl (1967). Dokumente zur Geschichte der iranischen Hunnen in Baktrien und Indien. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. OCLC 2561645. GGKEY:4TALPN86ZJB.

- 1 2 Gudrun Melzer; Lore Sander (2000). Jens Braarvig, ed. A Copper Scroll Inscription from the Time of the Alchon Huns. Buddhist manuscripts. 3. Oslo: Hermes Pub. pp. 251–278. ISBN 9788280340061.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ Rienjang, Wannaporn; Stewart, Peter (2018). Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd-24th March, 2017. Archaeopress. p. 23. ISBN 9781784918552.

- ↑ Neelis, Jason (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. BRILL. p. 159. ISBN 9004181598.

- ↑ Tandon, Pankaj (2015). "The Identity of Prakasaditya" (PDF). ournal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 25 (4): 647–668. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 199. ISBN 9781474400312.

- ↑ CNG Coins

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alchon Huns. |

- Nezak Kings in Zabulistan and Kabulistan Coin Cabinet of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

- Coinage of the Hephthalites/ Alchons, Grifterrec

| Timeline and cultural period |

Northwestern India (Punjab-Sapta Sindhu) |

Indo-Gangetic Plain | Central India | Southern India | ||

| Upper Gangetic Plain (Kuru-Panchala) |

Middle Gangetic Plain | Lower Gangetic Plain | ||||

| IRON AGE | ||||||

| Culture | Late Vedic Period | Late Vedic Period (Brahmin ideology)[lower-alpha 1] Painted Grey Ware culture |

Late Vedic Period (Kshatriya/Shramanic culture)[lower-alpha 2] Northern Black Polished Ware |

Pre-history | ||

| 6th century BC | Gandhara | Kuru-Panchala | Magadha | Adivasi (tribes) | ||

| Culture | Persian-Greek influences | "Second Urbanisation" Rise of Shramana movements Jainism - Buddhism - Ājīvika - Yoga |

Pre-history | |||

| 5th century BC | (Persian rule) | Shishunaga dynasty | Adivasi (tribes) | |||

| 4th century BC | (Greek conquests) | Nanda empire | ||||

| HISTORICAL AGE | ||||||

| Culture | Spread of Buddhism | Pre-history | Sangam period (300 BC – 200 AD) | |||

| 3rd century BC | Maurya Empire | Early Cholas Early Pandyan Kingdom Satavahana dynasty Cheras 46 other small kingdoms in Ancient Thamizhagam | ||||

| Culture | Preclassical Hinduism[lower-alpha 3] - "Hindu Synthesis"[lower-alpha 4] (ca. 200 BC - 300 AD)[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6] Epics - Puranas - Ramayana - Mahabharata - Bhagavad Gita - Brahma Sutras - Smarta Tradition Mahayana Buddhism |

Sangam period (continued) (300 BC – 200 AD) | ||||

| 2nd century BC | Indo-Greek Kingdom | Shunga Empire Maha-Meghavahana Dynasty |

Early Cholas Early Pandyan Kingdom Satavahana dynasty Cheras 46 other small kingdoms in Ancient Thamizhagam | |||

| 1st century BC | ||||||

| 1st century AD | Kuninda Kingdom | |||||

| 2nd century | Kushan Empire | |||||

| 3rd century | Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom | Kushan Empire | Western Satraps | Kamarupa kingdom | Kalabhra dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) | |

| Culture | "Golden Age of Hinduism"(ca. AD 320-650)[lower-alpha 7] Puranas Co-existence of Hinduism and Buddhism | |||||

| 4th century | Kidarites | Gupta Empire Varman dynasty |

Kalabhra dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) Kadamba Dynasty Western Ganga Dynasty | |||

| 5th century | Hephthalite Empire | Alchon Huns | Kalabhra dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) Vishnukundina | |||

| 6th century | Nezak Huns Kabul Shahi |

Maitraka | Adivasi (tribes) | Badami Chalukyas Kalabhra dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) | ||

| Culture | Late-Classical Hinduism (ca. AD 650-1100)[lower-alpha 8] Advaita Vedanta - Tantra Decline of Buddhism in India | |||||

| 7th century | Indo-Sassanids | Vakataka dynasty Empire of Harsha |

Mlechchha dynasty | Adivasi (tribes) | Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) Pandyan Kingdom(Revival) Pallava | |

| 8th century | Kabul Shahi | Pala Empire | Pandyan Kingdom Kalachuri | |||

| 9th century | Gurjara-Pratihara | Rashtrakuta dynasty Pandyan Kingdom Medieval Cholas Pandyan Kingdom(Under Cholas) Chera Perumals of Makkotai | ||||

| 10th century | Ghaznavids | Pala dynasty Kamboja-Pala dynasty |

Kalyani Chalukyas Medieval Cholas Pandyan Kingdom(Under Cholas) Chera Perumals of Makkotai Rashtrakuta | |||

References and sources for table References Sources

| ||||||

.jpg)