Kidarites

Kidarite kingdom | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 320–500 | |||||||||

Tamga of the Kidarites

| |||||||||

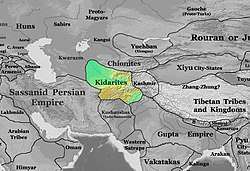

The Kidarite kingdom in 400 CE. | |||||||||

| Capital | Bactria, Peshwar, Taxila | ||||||||

| Common languages | Bactrian (written) | ||||||||

| Government | Nomadic empire | ||||||||

| Kushanshah | |||||||||

• fl. 320 | Kidara | ||||||||

• fl. 425 | Varhran I | ||||||||

• fl. 500 | Kandik | ||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||

• Established | 320 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 500 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||

The Kidarites (Chinese: 寄多羅 Jiduolo[1]) were a dynasty that ruled Bactria and adjoining parts of Central Asia and South Asia in the 4th and 5th centuries CE. The Kidarites belonged to a complex of peoples known collectively in India as the Huna and/or in Europe as the Xionites (from the Iranian names Xwn/Xyon). (The Huna/Xionite tribes are often linked, albeit controversially, to the Huns who invaded Eastern Europe during a similar period).

Named after Kidara, their founding ruler and purported membership of a clan named Ki, the Kidarites appear to have been a part of a Huna horde known in Latin sources as the Kermichiones (from the Iranian Karmir Xyon) or "Red Huna". The Kidarites established the first of four major Xionite/Huna states in Central Asia, followed by the Hephthalites, the Alchon, and the Nezak.

In 360-370 CE, a Kidarite kingdom was established in Central Asian regions previously ruled by the Sasanian Empire, replacing the Kushano-Sasanians in Bactria.[2][3] Thereafter the Sasanian Empire roughly stopped at Merv.[3]

Origins

A nomadic people, the Kidarites appear to have originated in the Altai Mountains region. Some scholars believe that the Kidarites were "Europid" in appearance, with some East Asian (i.e. Mongoloid) admixture.[5] On Kidarite coins their rulers are depicted as beardless or clean-shaven – a feature of Inner Asian cultures at the time (as opposed, for example, to the Iranian cultures of South Central Asia at the time).[6] The Kidarites were depicted as mounted archers on the reverse of coins.[7] They were also known to practice artificial cranial deformation.[8]

The Kidarites appear to have been synonymous with the Karmir Xyon ("Red Xionites" or, more controversially, "Red Huns"),[9][10] – a major subdivision of the Xionites, alongside the Spet Xyon ("White Xionites"). The name of their eponymous ruler Kidara (fl. 350-385 CE) may be cognate with the Turkic word Kidirti meaning "west", suggesting that the Kidarites were originally the westernmost of the Xionites, and the first to migrate from Inner Asia.[11] Chinese sources suggest that when the Uar (滑 Huá) were driven westward by the Later Zhao state, circa 320 CE, from the area around Pingyang (平陽; modern Linfen, Shanxi), it put pressure on Xionite-affiliated peoples, such as the Kidarites, to migrate. Another theory is that climate change in the Altai during the 4th century caused various tribes to migrate westward and southward.[11]

Contemporary Chinese and Roman sources suggest that, during the 4th century, the Kidarites began to encroach on the territory of Greater Khorasan and the Kushan Empire – migrating through Transoxiana into Bactria,[12] where they were initially vassals of the Kushans and adopted many elements of Kushano-Bactrian culture. The Kidarites also initially put pressure on the Sasanian Empire, but later served as mercenaries in the Sassanian army, under which they fought the Romans in Mesopotamia, led by a chief named Grumbates (fl. 353–358 CE). Some of the Kidarites apparently became a ruling dynasty of the Kushan Empire, leading to the epithet "Little Kushans".[13][14]

Kidarite kingdom

Sources

The first 4th century evidence are gold coins discovered in Balkh dating from c. 380, where 'Kidara' is usually interpreted in a legend in the Bactrian language. Most other data we currently have on the Kidarite kingdom are from Chinese and Byzantine sources from the middle of the 5th century. The Kidarites were the first Huna to bother India. Indian records note that the Hūna had established themselves in modern Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier Province by the first half of the 5th century, and the Gupta emperor Skandagupta had repelled a Hūna invasion in 455. The Kidarites are the last dynasty to regard themselves (on the legend of their coins) as the inheritors of the Kushan empire, which had disappeared as an independent entity two centuries earlier.

Migration into Bactria

Around 350, the Sasanian Emperor Shapur II (ruled 309 to 379) had to interrupt his conflict with the Romans, and abandon the siege of Nisibis,[11] in order to face nomadic threats in the east: he was attacked in the east by Scythian Massagetae and other Central Asian tribes.[15] Around this time, Xionite/Huna tribes, most likely the Kidarites, whose king was Grumbates, make an appearance as an encroaching threat upon Sasanian territory as well as a menace to the Gupta Empire (320-500CE).[1]

After a prolonged struggle (353–358) they were forced to conclude an alliance, and their king Grumbates accompanied Shapur II in the war against the Romans, agreeing to enlist his light cavalrymen into the Persian army and accompanying Shapur II. The presence of "Grumbates, king of the Chionitae" and his Xionites with Shapur II during campaigns in the Western Caspian lands, in the area of Corduene, is described by the contemporary eyewitness Ammianus Marcellinus:[16]

Grumbates Chionitarum rex novus aetate quidem media rugosisque membris sed mente quadam grandifica multisque victoriarum insignibus nobilis.

"Grumbates, the new king of the Xionites, while he was middle aged, and his limbs were wrinkled, he was endowed with a mind that acted grandly, and was famous for his many, significant victories."

The presence of Grumbates alongside Shapur II is also recorded at the successful Siege of Amida in 359, in which Grumbates lost his son:[11]

"Grumbates, king of the Chionitae, went boldly up to the walls to effect that mission, with a brave body of guards; and when a skilful reconnoitrer had noticed him coming within shot, he let fly his balista, and struck down his son in the flower of his youth, who was at his father's side, piercing through his breastplate, breast and all; and he was a prince who in stature and beauty was superior to all his comrades. "

Later the alliance fell apart, and by the time of Bahram IV (388-399) the Sasanians had lost numerous battles against the Kidarites.[11] The migrating Kidarites then settled in Bactria, where they replaced the Kushano-Sasanids, a branch of the Sasanids that had displaced the weakening Kushans in the area two centuries before.[2] It is thought that they were in firm possession of the region of Bactria by 360 CE.[11] Since this area corresponds roughly to Kushanshahr, the former western territories of the Kushans, Kidarite ruler Kidara called himself "Kidara King of the Kushans" on his coins.[19]

According to Priscus, the Sasanian Empire was forced to pay tribute to the Kidarites, until the rule of Yazdgird II (ruled 438-457), who refused payment.[20]

The Kidarites based their capital in Samarkand , where they were at the center of Central Asian trade networks, in close relation with the Sogdians.[3] The Kidarites had a powerful administration and raised taxes, rather efficiently managing their territories, in contrast to the image of barbarians bent on destruction given by Persian accounts.[3]

Expansion to northwest India

The Kidarites consolidated their power in Northern Afghanistan during the 420s before conquering Peshawar and part of northwest India, then turning north to conquer Sogdiana in the 440s. The Kidarites were cut from their Bactrian nomadic roots by the rise of the Hephthalites in the 450s. The Kidarites also seem to have been defeated by the Sasanian emperor Peroz in 467 CE, with Peroz reconquering Balkh and issuing coinage there as "Peroz King of Kings".[3] It is probably the rise of the Hephthalites and the defeats against the Sasanians which pushed the Kidarites into northern India.

Conflicts with the Gupta Empire

The Kidarites may have confronted the Gupta Empire during the rule of Kumaragupta I (414–c. 455 CE) as the latter recounts some conflicts,although very vaguely, in his Mandsaur inscription.[21] The Bhitari pillar inscription of Skandagupta, inscribed by his son Skandagupta (c. 455 – c. 467 CE), recalls much more dramatically the near-annihilation of the Gupta Empire, and recovery though military victories against the attacks of the Pushyamitras and the Hunas.[11] The Kidarites are the only Hunas who could have attacked India at the time, as the Hephthalites were still trying to set foot in Bactria in the middle of the 5th century.[12] In the Bhitari inscription, Skandagupta clearly mentions a conflagrations with the Hunas, even though some portions of the inscription have disappeared:

"(Skandagupta), by whose two arms the earth was shaken, when he, the creator (of a disturbance like that) of a terrible whirlpool, joined in close conflict with the Hûnas; . . . . . . among enemies . . . . . . arrows . . . . . . . . . . . . proclaimed . . . . . . . . . . . . just as if it were the roaring of (the river) Ganga, making itself noticed in (their) ears."

After these encounters, the Kidarites seem to have retained the western part of the Gupta Empire.[11] The Huna invasion are said to have seriously damaged Indo-Roman trade relations, which the Gupta Empire had greatly benefited from. The Guptas had been exporting numerous luxury products such as silk, leather goods, fur, iron products, ivory, pearl or pepper from centers such as Nasik, Paithan, Pataliputra or Benares etc. The Huna invasion probably disrupted these trade relations and the tax revenues that came with it.[22]

Conflict with Sasanian emperor Peroz I and the Hephthalites

Around 457, the Kidarites were again in conflict against the Sasanians under Yazdegerd II. A "Kidarite dynasty", south of the Oxus, was at war with the Sassanids in the fifth century. The Sasanian Emperor Peroz I (ruled 459–484) fought Kidara and then his son Kungas, forcing Kungas to leave Bactria. The Kidarites, who had established themselves in parts of Transoxiana during the reign of the Sasanian king Shapur II, and had a long history of conflicts with the Sasanians. The latter stopped paying tributes to Kidarites in the early 460s, thus starting a new war between these two states.

During the start of the war, however, Peroz did not have enough manpower to fight them, and therefore asked for financial aid by the Byzantine Empire, who declined his request.[24] Peroz then offered peace to the leader of the Kidarites, Kunkhas, and offered him his sister in marriage. However, Peroz tried to trick Kunkhas, and sent a woman of low status instead. After some time Kunkhas found about Peroz's false promise, and then in turn tried to trick him, by requesting him to send military experts to strengthen his army. However, when a group of 300 military experts arrived to the court of Kunkhas at Balaam (either the same city as Balkh or a city in Sogdia), they were either killed or disfigured and sent back to Iran, with the information that Kunkhas did this due to Peroz's false promise.

What happened after remains obscure, it is only known that by 467, Peroz, with Hephthalite aid, reportedly managed to capture Balaam (possibly Balkh) and put an end to Kidarite rule in Transoxiana once and for all.[11][24] Although the Kidarites still controlled some places such as Gandhara and Punjab, they would never be an issue for the Sasanians again.[2]

Kidarite successors

Many small Kidarite kingdoms seems to have survived in northwest India up to the conquest by the Hephthalites during the last quarter of the 5th century. They are known through their coinage. They were particularly present in Jammu and Kashmir, such as king Vinayaditya, but their coinage was much debased.

The Kidarites were soon overwhelmed by the Hephthalites.[25][16] By 520, Gandhara was definitely under Hephthalite control, according to Chinese pilgrims.[11]

The Alchon followed the Kidarites into India circa 500, invading Indian territory as far as Eran and Kausambi.

Anania Shirakatsi states in his Ashkharatsuyts, written in 7th century, that one of the Bulgar tribes, known as the Kidar were part of the Kidarites. The Kidar took part in Bulgar migrations across the Volga into Europe.[26]

Main Kidarite rulers

| Kidara I | fl. c. 320 CE |

| Kungas | 330's ? |

| Varhran I | fl. c. 340 |

| Grumbates | c. 358-c. 380 |

| Kidara (II ?) | fl. c. 360 |

| Brahmi Buddhatala | fl. c. 370 |

| (Unknown) | fl. 388/400 |

| Varhran (II) | fl. c. 425 |

| Goboziko | fl. c. 450 |

| Salanavira | mid 400's |

| Vinayaditya | late 400's |

| Kandik | early 500's |

See also

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Tajikistan |

| Timeline |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Turkmenistan |

|

|

References and notes

- 1 2 Touraj Daryaee (2009), Sasanian Persia, London and New York: I.B.Tauris, p. 17

- 1 2 3 Sasanian Seals and Sealings, Rika Gyselen, Peeters Publishers, 2007, p.1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas, Cambridge University Press, 2014 p.284sq

- ↑ "CNG: eAuction 208. HUNNIC TRIBES, Kidarites. Kidara. Circa AD 350-385. AR Drachm (28mm, 3.97 g, 3h)". www.cngcoins.com. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Ancient History of Central Asia: Yuezhi origin Royal Peoples: Kushana, Huna, Gurjar and Khazar Kingdoms, Adesh Katariya, 2007, p. 171.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Iranica, article Kidarites: "On Gandhāran coins bearing their name the ruler is always clean-shaven, a fashion more typical of Altaic people than of Iranians".

- ↑ History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, page 120, https://books.google.com/books?id=883OZBe2sMYC&pg=PA120

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas, page 185, https://books.google.com/books?id=67dUBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA185

- ↑ Kuṣāṇa Coins and Kuṣāṇa Sculptures from Mathurā, Gritli von Mitterwallner, Frederic Salmon Growse, page 49, https://books.google.com/books?id=uufVAAAAMAAJ

- ↑ Ancient Coin Collecting VI: Non-Classical Cultures, Wayne G. Sayles, p. 79, https://books.google.com/books?id=YTGRcVLMg6MC&pg=PA78

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 The Huns, Hyun Jin Kim, Routledge, 2015 p.50 sq

- 1 2 History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, Unesco p.119 sq

- ↑ COINS OF THE TOCHARI, KUSHÂNS, OR YUE-TI, A. Cunningham, The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society, https://www.jstor.org/stable/42680025?seq=12#page_scan_tab_contents

- ↑ A NOTE ON KIDARA AND THE KIDARITES, WILLIAM SAMOLIN, Central Asiatic Journal, Vol. 2, No. 4 (1956), pp. 295-297, „The Yueh-chih origin of Kidara is clearly established...“, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41926398?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- ↑ electricpulp.com. "ŠĀPUR II – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- 1 2 History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, Unesco p.38 sq

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 18.6.22

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 18.6.22

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas p.286

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas p.287

- ↑ Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D by Kailash Chand Jain p.242

- ↑ Longman History & Civics ICSE 9 by Singh p.81

- ↑ "CNG: The Coin Shop. HUNNIC TRIBES, Kidarites. "King B". Late 4th-early 5th century AD. AR Drachm (28mm, 4.05 g, 3h)". www.cngcoins.com. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- 1 2 Zeimal 1996, p. 130.

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ The Bulgarians: from pagan times to the Ottoman conquest(1976), David Marshall Lang, pages 31 and 204: "Armenian geographer states that the principal tribes of Bulgars were called Kuphi-Bulgars, Duchi-Bulgars, Oghkhundur-Bulgars, and Kidar-Bulgars, by the last-named of which he meant the Kidarites, a branch of the Huns." https://books.google.bg/books?redir_esc=y&id=8EppAAAAMAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=kidar

Sources

- Zeimal, E. V. (1996). "The Kidarite kingdom in Central Asia". History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III: The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 119–135. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.

- ENOKI, K., « On the Date of the Kidarites (I) », Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko, 27, 1969, p. 1–26.

- GRENET, F. « Regional Interaction in Central Asia and North-West India in the Kidarite and Hephtalite Period », in SIMS-WILLIAMS, N. (ed.), Indo-Iranian Languages and Peoples, (Proceedings of the British Academy), London, 2002, p. 203–224.