Nangarhar Province

| Nangarhar | |

|---|---|

| Province | |

A U.S. Army helicopter in Nangarhar province (December 2013) | |

Map of Afghanistan with Nangarhar highlighted | |

| Coordinates (Capital): 34°15′N 70°30′E / 34.25°N 70.50°ECoordinates: 34°15′N 70°30′E / 34.25°N 70.50°E | |

| Country |

|

| Capital | Jalalabad |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Hayatallah Hayat[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,727 km2 (2,983 sq mi) |

| Population (2013)[2] | |

| • Total | 1,436,000 |

| • Density | 190/km2 (480/sq mi) |

| Time zone | GMT+4:30 |

| ISO 3166 code | AF-NAN |

| Main languages | Pashto and Persian |

Nangarhār (Pashto: ننګرهار; Persian: ننگرهار) is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, located in the eastern part of the country. It is divided into twenty-two districts and has a population of about 1,436,000.[2] The city of Jalalabad is the capital of Nangarhar province.

History

Etymology

Henry George Raverty theorized that the word Nangarhar is derived from the Pashto term nang-nahlr ("nine streams"), which appears in some Persian language chronicles. The term supposedly refers to nine streams originating from Safed Koh. However, according to S. H. Hodivala, the name of the province derives from the Sanskrit term Nagarahara, which appears in a 9th century inscription discovered at Ghosrawa in present-day Bihar, India. Nang-go-lo-ho, the Chinese transcription of this term, appears in the annals of the Song dynasty of China. Henry Walter Bellew derived the name from the Sanskrit nava-vihara, meaning "nine viharas".[3]

Early history

The province was originally part of the Achaemenid Empire, in the Gandhara satrapy (province). The Nangarhar province territory and the Eastern Iranian peoples there fell to the Maurya Empire, which was led by Chandragupta Maurya. The Mauryas introduced Hinduism and Buddhism to the region, and were planning to capture more territory in Central Asia until they faced local Greco-Bactrian forces. Seleucus is said to have reached a peace treaty with Chandragupta by giving control of the territory south of the Hindu Kush to the Mauryas upon intermarriage and 500 elephants.

Alexander took these away from the Mauryans and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.[4]

— Strabo, 64 BCE–24 CE

Some time after, as he was going to war with the generals of Alexander, a wild elephant of great bulk presented itself before him of its own accord, and, as if tamed down to gentleness, took him on its back, and became his guide in the war, and conspicuous in fields of battle. Sandrocottus, having thus acquired a throne, was in possession of India, when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness; who, after making a league with him, and settling his affairs in the east, proceeded to join in the war against Antigonus. As soon as the forces, therefore, of all the confederates were united, a battle was fought, in which Antigonus was slain, and his son Demetrius put to flight.[5]

Having consolidated power in the northwest, Chandragupta pushed east towards the Nanda Empire. Afghanistan's significant ancient tangible and intangible Buddhist heritage is recorded through wide-ranging archeological finds, including religious and artistic remnants. Buddhist doctrines are reported to have reached as far as Balkh even during the life of the Buddha (563 BCE to 483 BCE), as recorded by Husang Tsang.

In this context a legend recorded by Husang Tsang refers to the first two lay disciples of Buddha, Trapusa and Bhallika responsible for introducing Buddhism in that country. Originally these two were merchants of the kingdom of Balhika, as the name Bhalluka or Bhallika probably suggests the association of one with that country. They had gone to India for trade and had happened to be at Bodhgaya when the Buddha had just attained enlightenment.[6]

Song Yun, a Chinese monk visited Nangarhar in 520 AD, claimed that the people in the area were Buddhists. Yun came across a vihara (monastery) in Nangarhar (Na-lka-lo-hu) containing the skull of Buddha, and another of Kekalam (probably Mihtarlam in Laghman province) where 13 pieces of the cloak of Buddha and his 18 feet long mast were preserved. In the city of Naki, a tooth and hair of Buddha were preserved and in the Kupala cave Buddha's shadow reflected close to which he saw a stone tablet which was at that time considered to be related to Buddha (probably the stone tablet of Ashoka in Darūntah).[7]

The region fell to the Ghaznavids after defeating Jayapala in the late 10th century.[8][9][10] It later fell to the Ghorids followed by the Khaljis, Lodhis and the Moghuals, until finally becoming part of Ahmad Shah Durrani's Afghan Empire in 1747.

During the First Anglo-Afghan War, the invading British-led Indian forces were defeated on their way to Rawalpindi in 1842. British-led Indian forces returned in 1878 but retreated a couple of years later. Some fighting took place during the 1919 Third Anglo-Afghan War between the Afghan army that were led by King Amanullah Khan and British-Indians near the Durand Line border areas.

The province remained relatively calm until the 1980s Soviet–Afghan War. Nangarhar was used by pro-Pakistani mujahideen (rebel forces) fighting against the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. The Pakistani-trained mujahideen received funding from the United States and Saudi Arabia. Many Arab fighters from the Arab World had been fighting against the government forces of Mohammad Najibullah, who ultimately defeated them near Jalalabad. In April 1992, Najibullah resigned as President and the various mujahideen took control over the country. When the 1992 Peshawar Accord failed, the mujahideen turned guns on each other and started a nationwide civil war. This was followed by the Taliban take-over in 1996 and the establishment of al-Qaeda training camps in Nangarhar province.

Recent history

Osama bin Laden held a strong position in Nangarhar during the late 1990s. He led a fight against US-led forces in the 2001 Tora Bora campaign. He ultimately escaped to Abottabad, Pakistan, where he was killed in a night raid by members of SEAL Team Six in 2011.

After the removal of the Taliban government and the formation of the Karzai administration in late 2001, U.S.-led Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) gradually established authority across the province. Despite this, Taliban insurgents continue to stage attacks against Afghan government forces. The Haqqani Network and militants loyal to Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant – Khorasan Province (ISIL-KP) are often blamed for the attacks, which sometimes include major suicide bombings. Several incursions by Pakistani military forces have also been reported in the districts next to the Durand Line border. The focus of the conflict is on the Kabul and Kunar rivers, which run through Nangarhar.

On April 13, 2017, U.S. President Donald J. Trump ordered a targeted strike on ISIL-KP by use of the second largest non-nuclear bomb in the U.S. arsenal at the time. The bomb was a 21,000 lb. weapon called the Massive Ordnance Air Blast Bomb; nicknamed the "Mother Of All Bombs" (MOAB). The intended target was ISIL militants hiding inside tunnels, most of whom came "from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Russia, India and other countries."[11] Mohammad Radmanish, spokesman for the Afghan Ministry of Defense stated: "Most militants killed in the attack were from Pakistan, India, Philippines, and Bangladesh."[11] It was the first time the MOAB had been used in combat.

Politics and governance

The current governor of the province is Hayatullah Hayat .[12] His predecessor was Saleem Khan Kunduzi who resigned on 22 October 2016. Gul Agha Sherzai served as the governor since 2004 but left in order to run in the 2014 Afghan presidential election. The city of Jalalabad serves as the capital of the province.

All law enforcement activities throughout the province are controlled by the Afghan National Police (ANP) along with the Afghan Local Police (ALP). The border with neighboring Pakistan is monitored by the Afghan Border Police (ABP). A provincial police chief is assigned to lead both the ANP and the ABP. The Police Chief represents the Ministry of the Interior in Kabul. The ANP and ABP are backed by the Afghan Armed Forces, including the NATO-led forces.

Nangarhar shares a border with the neighboring Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. The three regions share very close ties, with significant travel and commerce in both directions.

Healthcare

The percentage of households with clean drinking water fell from 43% in 2005 to 8% in 2011.[13] The percentage of births attended to by a skilled birth attendant increased from 22% in 2005 to 60% in 2011.[13]

Education

Nangarhar University is located in the provincial capital, Jalalabad. It is government-funded and provides higher education to nearly 6,000 students from the region.

A number of schools operate in the province, providing basic education to both boys and girls. The overall literacy rate (6+ years of age) increased from 29% in 2005 to 31% in 2011.[13] The overall net enrolment rate (6–13 years of age) increased from 39% in 2005 to 51% in 2011.[13]

Economy

The Jalalabad plain is one of the principal agricultural areas of Afghanistan. The strong agricultural base, coupled with the crucial trade route connecting Kabul with Peshawar, makes Nangarhar one of the more economically diverse and functional provinces of Afghanistan. Torkham is one of the major border crossings between Afghanistan and Pakistan. It is the busiest port of entry between the two countries, serving as a major economical hub for the province.

Nangarhar was once a major center of opium poppy production in the country, but by 2005 the province had reportedly decreased its production of poppy by up to 95%. This was to become one of the success stories of the Afghan poppy eradication program. However, the eradication program has often left peasant farmers destitute and, in 2006, farmers were reported to have surrendered their children to opium dealers in payment on their debts. The illicit poppy cultivation takes place in Khogiani, Ghanikhil, Chaparhar, Sherzad, Toorghar, Shenwari and other remote districts. The farmers cite a lack of water and also poverty as reasons for continued poppy cultivation. Poppy was also cultivated in Goshta District, Lalpura which borders Pakistan but now the people predominately cultivate wheat and other legal crops.[14]

Transportation

The Jalalabad Airport is located next to the city of Jalalabad. It serves the populations of Nangarhar, Kunar, Nuristan, and other close-by provinces.

The Kabul–Jalalabad Road runs throughout the province, linking Kabul with Jalalabad and extending east through Khyber Pass to Peshawar. It is one of the busiest major roads in Afghanistan.

Geography

Demographics

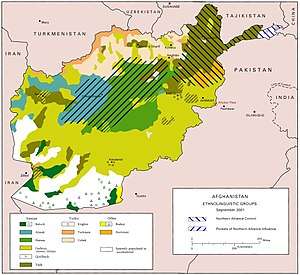

As of 2013, the total population of the province is about 1,436,000.[2] According to the Institute for the Study of War, "the population is overwhelmingly Pashtun; less than ten percent are Pashai, Tajik, Arab, or other minorities."[14] According to the Naval Postgraduate School, the ethnic groups of the province are as follows: 91.1% Pashtun; 3.6% Pashai; 2.6% Arab; 1.6% Tajik; and 2.1% other.[15] The 18th edition Ethnologue states on p. 48 that Nangarhar is the center of the (smaller) Northern Pashtu language in Afghanistan. Only 1 in 5 Afghan Pashtus use the Northern variety.

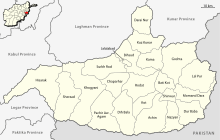

Districts

Nangarhar is divided into 22 districts, they are as follow:

| District | Capital | Population[16] | Area[17] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jalalabad | Jalalabad | 205,423 | Pashtun, Tajik, Arab, Pashais 90% Pashtun | |

| Haska Meyna | Haska Meyna | 33,294 | 100% Pashtun, | |

| Shinwar | 64,872 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Achin | 95,468 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Bihsud | 118,934 | 95% Pashtun, 5% Arab | ||

| Chaparhar | 57,339 | Pashtun 100% Pashtun | ||

| Darai Nur | 98,202 | 73% Pashtun, 27% Pashais | ||

| Bati Kot | 31,308 | Pashtun 100% Pashtun | ||

| Dur Baba | 13,479 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Goshta | 31,130 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Hisarak | 28,376 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Kama | 52,527 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Khogyani | Kaga | 111,479 | 100% Pashtun | |

| Kot | 52,154 | Created in 2005 within Rodat District100% Pashtun | ||

| Kuz Kunar | 42,823 | 98% Pashtun, 2% Pashais | ||

| Lal Pur | 18,997 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Momand Dara | 42,103 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Nazyan | 16,328 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Pachir Aw Agam | 40,141 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Rodat | 63,357 | Sub-divided in 2005 100% Pashtun | ||

| Sherzad | 63,232 | 100% Pashtun | ||

| Surkh Rod | 91,548 | 100% Pashtun |

Sports

The province is represented in domestic cricket competitions by the Nangarhar province cricket team. Jalalabad is considered the capital of Afghan cricket with many of the national players coming from the surrounding areas. National team member Hamid Hasan was born in the province.

De Spinghar Bazan is a regional team in the Roshan Afghan Premier League based in Jalalabad. Jalalabad Regional Football Tournament were four local team plays like Malang Jan, Shaheed Qasim, Afghan Refugees and Laghman for to find raw talent in Afghan Premier League.[18] Wrestling in Jalalabad was modernized by Davud Sulaymankhil, a Pashtun orator and athlete. Now, several wrestling teams (most notably the Suleim Wrestling Team founded by Davud Sulaymanhil) represent the province in national events.

Stadiums

- Ghazi Amanullah International Cricket Stadium is the first international standard cricket stadium in Afghanistan. It is located in the Ghazi Amanullah Town about 15 kilometres south-east of Jalalabad.[19]

- Sherzai Cricket Stadium, second cricket ground in Jalalabad

- Sirajul Emarah Football Stadium in Jalalabad

See also

References

- ↑ "Governor of eastern Afghan province sacked as security worsens". Reuters. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Settled Population of Nangargar province by Civil Division, Urban, Rural and Sex-2012-13" (PDF). Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Central Statistics Organization. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ↑ Shahpurshah Hormasji Hodivala (1979) [2862294]. Studies in Indo-Muslim History. 1. Islamic Book Service. p. 195. OCLC 2862294.

- ↑ Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul - The Name". American International School of Kabul. Archived from the original on 2010-08-30. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ↑ Historiarum Philippicarum libri XLIV, XV.4.19

- ↑ Puri, Baij Nath (1987). Buddhism in central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 352. ISBN 81-208-0372-8. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ↑ Chinese Travelers in Afghanistan. Alamahabibi.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ "AMEER NASIR-OOD-DEEN SUBOOKTUGEEN". Ferishta, History of the Rise of Mohammedan Power in India, Volume 1: Section 15. Packard Humanities Institute. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ↑ Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1987). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. 2. BRILL. p. 151. ISBN 90-04-08265-4. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ↑ "Afghan and Afghanistan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- 1 2 "Bangladeshis, Indians among militants killed by MOAB". Pajhwok Afghan News. April 20, 2017. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ↑ "Pakistan to open visa facilities in Afghan provinces". Pajhwok Afghan News. November 14, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Archive, Civil Military Fusion Centre, https://www.cimicweb.org/AfghanistanProvincialMap/Pages/Nangarhar.aspx

- 1 2 "Nangarhar Province". Understanding War. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ↑ "Nangarhar Province" (PDF). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies. Naval Postgraduate School. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ↑ "MRRD Provincial profile for Nangarhar Province" (PDF). Mrrd.gov.af. 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ↑ Andrew Ross. "Afghanistan Geographic & Thematic Layers". Fao.org. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ↑ Afghan Premier League

- ↑ "International cricket stadium inaugurated in Nangarhar (Video)" (in Pashto). Pajhwok Afghan News. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nangarhar Province. |