Chandragupta Maurya

| Chandragupta Maurya | |

|---|---|

Chandragupta Maurya and Jain sage Acharya Bhadrabahu depicted in a medieval stone carving from Shravanabelagola, Karnataka[1] | |

| 1st Mauryan emperor | |

| Reign | c. 321 – c. 297 BCE[2][3] |

| Coronation | c. 321 BCE |

| Predecessor | Dhana Nanda |

| Successor | Bindusara (son) |

| Born |

c. 340 BCE Pataliputra, Magadha (modern-day Patna, Bihar) |

| Died |

297 BCE[3] Shravanabelagola, Karnataka (Jain legend)[4] |

| Spouse | Durdhara |

| Issue | Bindusara |

| Dynasty | Maurya |

| Father | unknown |

| Mother | Mura[5][6] |

| Religion | Jainism[7] |

| Maurya Empire (322 BCE–180 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

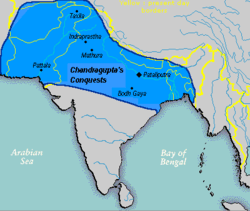

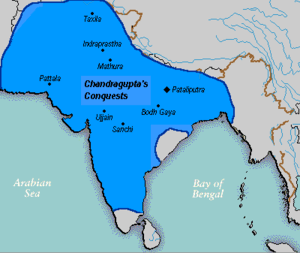

Chandragupta Maurya (reign: 321–297 BCE) was the founder of the Maurya Empire, which was originally centered in the Magadha region, but eventually expanded to include a larger part of ancient India.[2][8]

Of obscure origins, he was counselled and guided in his adolescent years by Chanakya, who is traditionally identified as Kauṭilya, the author of the Arthashastra (a treatise of statehood and nation building).[9][2] Chandragupta, under the tutelage of Chanakya, conquered the Nanda Empire and the eastern provinces of the Seleucid Empire,[10] thus establishing the largest empire that would exist in the Indian subcontinent.[2][11][12] Chandragupta's life and accomplishments are described in ancient Hindu, Buddhist and Greek texts, but they vary significantly in details from the Jaina accounts.[13] Megasthenes served as a Greek ambassador in his court for four years.[8] In Greek and Latin accounts, Chandragupta is known as Sandrokottos and Androcottus.[14]

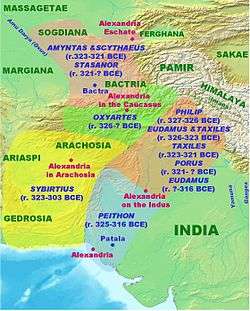

Chandragupta Maurya was a pivotal figure in the history of India. Prior to his consolidation of power, Alexander the Great had invaded the northwest Indian subcontinent, but would abandon further campaigning into India in 326 BCE due to a mutiny in his army.[15] The Macedonian Empire left behind satrapies in the disputed northwestern Indian subcontinent. The region, previously being governed by the Achaemenid Empire since the conquests of Darius the Great, was once again contested over. The Indus Valley and adjoining regions would be conquered by Chandragupta during the Seleucid–Mauryan war. The Mauryan Empire would eventually extend from Bangladesh to Afghanistan, and incorporate most of the Indian subcontinent.[16][11] During the reign of Chandragupta's grandson, Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire would form the largest empire documented in Indian history.[17][18][19]

After unifying much of India, Chandragupta and Chanakya passed a series of major economic and political reforms. He established a strong central administration from Pataliputra (now Patna), patterned after Chanakya's text on governance and politics, the Arthashastra.[20] Chandragupta's India was characterised by an efficient and highly organised structure. The empire built infrastructure such as irrigation, temples, mines and roads, leading to a strong economy.[21][22] With internal and external trade thriving and agriculture flourishing, the empire built a large and trained permanent army to help expand and protect its boundaries. Chandragupta's reign, as well the dynasty that followed him, was an era when many religions thrived in India, with Buddhism, Jainism and Ajivika gaining prominence.[23][24] Chandragupta is accredited to have followed Jainism later in his life. He first renounced his kingdom, and parted ways with his wealth and power. Ultimately Chandragupta, when relinquishing his kingdom, resided in Karnataka where he took up Sallekhana – the Jain religious ritual of peacefully welcoming death by fasting.[note 1] His legacy includes his grandson, Emperor Ashoka, who was famous for ruling most of the Indian subcontinent and spreading Buddhism throughout the known world as ascribed in his historic pillars, known as the Edicts of Ashoka.[25][26]

Biographical sources

The sources which describe the life of Chandragupta Maurya vary in details, and are found in Jain, Buddhist, Brahmanic (Hindu), Latin and Greek literature:[27]

- Jain sources are Bhadrabahu's Kalpasutra and Hemachandra's Parisishtaparvan.

- Hindu sources are the Puranas, Chanakya's Arthashastra, Vishakhadatta's Mudrarakshasa, Somadeva's Kathasaritsagara and Kshemendra's Brihatkathamanjari.

- Buddhist sources are Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Mahavamsa tika and Mahabodhivamsa.

- Greek and Latin sources include those by Nearchus, Onesicritus, Aristobulus, Strabo, Megasthenes, Diodorus, Arrian, Pliny the Elder, Plutarch and Justin.

Early life

Chandragupta's ancestry, birth year and family as well as early life are unclear.[28] This contrasts with abundant historical records, both in Indian and classical European sources, that describe his reign and empire.[29] The Greek and Latin literature phonetically transcribes Chandragupta, referring to him with the names "Sandrokottos" or "Androcottus".[14][30] According to Radhakumud Mookerji

.jpg)

- The Greek sources are the oldest recorded versions available, and mention his rise in 322/321 BCE after Alexander the Great ended his campaign in 325 BCE. These sources state Chandragupta to be of non-princely and non-warrior ancestry, to be of a humble commoner birth.[31][32]

- The Buddhist sources, written centuries later, claim that both Chandragupta and his grandson, the great patron of Buddhism called Ashoka, were of noble lineage. Some texts link him to the same family of Sakyas from which the Buddha came, adding that his epithet Moriya (Sanskrit: Maurya, Mayura) comes from Mora, which in Pali means peacock. Most Buddhist texts state that Chandragupta was a Kshatriya, the Hindu warrior class in Magadha and a student of Chanakya.[20][2] The Buddhist texts are inconsistent, with some including legends about a city named "Moriya-nagara" where all buildings were made of bricks colored like the peacock's resplendent neck.[33]

- The Jain sources, also written centuries later, claim Chandragupta to be the son of a village chief, a village known for raising peacocks.[33]

- The Hindu sources are similarly from later centuries. They state that Chandragupta was a student of Chanakya (also called Kautilya) of humble birth.[34] The Puranas composed after about the 3rd century CE mention that Kautilya was a Brahmin, praise Kautilya, mention Chandragupta but most are silent about his lineage or origins.[34] A few Hindu texts state that he was born to a Shudra woman, alternatively in a peacock rearing family – a profession that is neither priestly nor warrior.[34] An Ashokan pillar discovered and excavated in Nandangarh, suggests that a peacock was the emblem of Maurya dynasty and likely linked to the dynastic lineage.[35]

According to Kaushik Roy, both Chandragupta Maurya and the Nanda dynasty he replaced were of Shudra lineage.[36] After his birth, he was orphaned and abandoned, raised as a son by a cowherding pastoral family, then, according to Buddhist texts, was picked up, taught and counselled by Chanakya.[2][37]

Youth in the Northwest

The Buddhist literature, which places the Mauryas in the same royal dynasty as the Buddha, states that Chandragupta, though born near Patna (Bihar) in Magadha, was taken by Chanakya for his training and education to Taxila, a town in what is now northern Pakistan. There he studied for eight years.[37] The Greek and Hindu texts state that Kautilya (Chanakya) was a native of the northwest Indian subcontinent, and Chandragupta was his resident student at the University of Taxila for eight years.[38][39]

According to Plutarch, in his Life of Alexander, Chandragupta ("Androcottus") met with Alexander the Great when he was a young man:[40]

"Androcottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth."

Building the Empire

According to the Buddhist text Mahavamsa tika, Chandragupta and his guru Chanakya began recruiting an army after he completed his studies at Taxila (now in Pakistan).[42] This was a period of wars, given that Alexander the Great had invaded the northwest subcontinent from Caucasus Indicus (also called Paropamisadae in ancient texts, now called the Hindu Kush mountain range). Alexander and the Greeks abandoned further campaigns of expansion in 325 BCE, and began a retreat to Babylon, leaving a legacy of Indian subcontinent regions ruled by new Greek governors and local rulers. A supply of warriors was already in place, and the future emperor and his teacher chose to build alliances with local rulers and a small mercenary army of their own. Chanakya also identified talent for future administration.[43] By 323 BCE, within two years of Alexander's retreat, this newly formed group had defeated some of the Greek-ruled cities in the northwest subcontinent.[44] Each victory led to an expanded army and territory. Chanakya provided the strategy, Chandragupta the execution, and together they began expanding eastward towards Magadha (Gangetic plains).[45]

Eastward expansion and the end of Nanda empire

Historically reliable details of Chandragupta's campaign into Pataliputra are unavailable; the legends written centuries later are inconsistent. According to Buddhist texts such as Milindapanha, which state Chandragupta descended from Sakyas (the family of the Buddha), Magadha was ruled by the evil Nanda dynasty, which Chandragupta, with Chanakya's counsel, easily conquered to restore dhamma.[46][47] In contrast, Hindu and Jain records suggest that campaign was bitterly fought, because the Nanda dynasty had a well trained, powerful army. Chandragupta and Chanakya built alliances and a formidable army of their own first.[48][47]

The Mudrarakshasa of Vishakhadatta as well as the Jain work Parishishtaparvan, for example, state that Chandragupta allied with a Himalayan king called Parvatka.[49] It is noted in the Chandraguptakatha that Chandragupta and Chanakya were initially rebuffed by the Nanda forces. Regardless, in the ensuing war, Chandragupta faced off against Bhadrasala, the commander of Dhana Nanda's armies.[50] He was eventually able to defeat Bhadrasala and Dhana Nanda in a series of battles, culminating in the siege of the capital city Pataliputra[51] and the conquest of the Nanda Empire around 322 BCE.[51] With the end of the Nanda dynasty, and possessing the resources of the Gangetic plains, Chandragupta put to work the statecraft strategies of Chanakya.[52] In his efforts to expand and consolidate an empire, Chandragupta may have allied with the King of Simhapura in Rajputana and Gajapati, King of Kalinga (modern day Odisha).[53]

The conquest was fictionalised in Mudrarakshasa, a political drama in Sanskrit by Vishakadatta composed 600 years later, probably sometime between 300 CE and 700 CE.[36] In another work, Questions of Milinda, Bhaddasala is named as a Nanda general during the conquest.[36] Plutarch does not discuss this conquest, but does estimate that Chandragupta's army would later number 600,000 by the time it had subdued all of India,[54] an estimate also given by Pliny. Pliny and Plutarch also estimated the Nanda Army strength in the east as 200,000 infantry, 80,000 cavalry, 8,000 chariots, and 6,000 war elephants. These estimates were based in part of the earlier work of the Seleucid ambassador to the Maurya, Megasthenes.[55]

In the fictional work of doubtful historicity Mudrarakshasa, Chandragupta was said to have first acquired Punjab, and then combined forces with a local king named Parvatka under the advice of Chanakya, and advanced upon the Nanda Empire.[56] Chandragupta laid siege to Kusumapura (or Pataliputra, now Patna), the capital of Magadha, with the help of mercenaries from areas already conquered and by deploying guerrilla warfare methods.[36][57] P. K. Bhattacharyya states that the empire was built by a gradual conquest of provinces after the initial consolidation of Magadha.[54]

| Territorial evolution of the Mauryan Empire | |

| |

Conquest of Seleucid northwest regions

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Chandragupta and his Brahmin counsellor and chief minister Chanakya began their empire building in the north-western Indian subcontinent (modern-day Pakistan).[59][60] Alexander had left satrapies (described as "prefects" in classical Western sources) in place in 324 BCE. Chandragupta's mercenaries may have assassinated two of his governors, Nicanor and Philip.[61][51] The satrapies he fought probably included Eudemus, who left the territory in 317 BCE; and Peithon, governing cities near the Indus River until he too left for Babylon in 316 BCE. The Roman historian Justin, about 500 years later, described how "wild lions and elephants" instinctively revered him, and how he conquered the north-west:

While he (Sandrocottus [Chandragupta]) was lying asleep, after his fatigue, a lion of great size having come up to him, licked off with his tongue the sweat that was running from him, and after gently waking him, left him. Being first prompted by this prodigy to conceive hopes of royal dignity, he drew together a band of robbers, and solicited the Indians to support his new sovereignty. Some time after, as he was going to war with the generals of Alexander, a wild elephant of great bulk presented itself before him of its own accord, and, as if tamed down to gentleness, took him on its back, and became his guide in the war, and conspicuous in fields of battle. Sandrocottus, having thus acquired a throne, was in possession of India, when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness; who, after making a league with him, and settling his affairs in the east, proceeded to join in the war against Antigonus. As soon as the forces, therefore, of all the confederates were united, a battle was fought, in which Antigonus was slain, and his son Demetrius put to flight.

— Marcus Junianus Justinus, 2nd-century CE, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, Book XV, Translator: John Selby Watson, XV.4.19

War and marriage alliance with Seleucus

Seleucus I Nicator, a Macedonian general of Alexander, who, in 312 BCE, established the Seleucid Kingdom with its capital at Babylon, reconquered most of Alexander's former empire in Asia and put under his own authority the eastern territories as far as Bactria and the Indus (Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55),[62] and in 305 BCE he entered into conflict with Chandragupta[63] (in Greek Sandrocottus):

Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapuria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus. He crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship. Some of these exploits were performed before the death of Antigonus and some afterward.

According to R. C. Majumdar and D. D. Kosambi, Seleucus appears to have fared poorly, having ceded large territories west of the Indus to Chandragupta. The Maurya Empire added Arachosia (modern Kandahar), Gedrosia (modern Balochistan), Paropamisadae (or Gandhara).[64][65][lower-alpha 1]

According to Strabo, Chandragupta engaged in a marital alliance with Seleucus to formalise the peace treaty:[67]

The Indians occupy in part some of the countries situated along the Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians: Alexander deprived the Ariani of them, and established there settlements of his own. But Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus in consequence of a marriage contract (Epigamia, Greek: Ἐπιγαμία), and received in return five hundred elephants.

The details of the engagement treaty are not known,[70] but since the extensive sources available on Seleucus never mention an Indian princess, it is thought that the marital alliance went the other way, with Chandragupta himself or his son Bindusara marrying a Seleucid princess, in accordance with contemporary Greek practices to form dynastic alliances.[71] An Indian Puranic source, the Pratisarga Parva of the Bhavishya Purana, described the marriage of Chandragupta with a Greek ("Yavana") princess, daughter of Seleucus,[72] before accurately detailing early Mauryan genealogy:

"Chandragupta married with a daughter of Suluva, the Yavana king of Pausasa.[73] Thus, he mixed the Buddhists and the Yavanas. He ruled for 60 years. From him, Vindusara was born and ruled for the same number of years as his father. His son was Ashoka.

In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500 war elephants, which played a key role in the victory of Seleucus at the Battle of Ipsus.[76][67][77][78] In addition to this treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Antiochos sent Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Maurya court at Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar state).[79]

According to Greek sources, the two rulers maintained friendly relations and presents continued to be exchanged between them. Classical sources have recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus:[71]

"And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters as to make people more amorous. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love" Athenaeus of Naucratis, "The deipnosophists" Book I, chapter 32 [80][71]

Southern conquest

After annexing Seleucus' provinces west of the Indus river, Chandragupta had a vast empire extending across the northern parts of the Indian Sub-continent, from the Bay of Bengal to the Arabian Sea. Chandragupta then began expanding his empire further south beyond the barrier of the Vindhya Range and into the Deccan Plateau.[51] By the time his conquests were complete, Chandragupta's empire extended over most of the Indian subcontinent.[81]

A "Moriya" war in south is referred three times in the Tamil work Ahananuru, and once in Purananuru. These mention how Moriya army chariots cut through rocks, but it is unclear if this refers to Chandragupta Maurya or the Moriyas in the Deccan region of the 5th century CE.[82]

Army

Chandragupta's army was large, well trained and paid directly by the state as suggested by his counsellor Chanakya. It was estimated at hundreds of thousands of soldiers in Greek accounts.[83] For example, his army is mentioned to have 400,000 soldiers, according to Strabo:

Megasthenes was in the camp of Sandrocottus, which consisted of 400,000 men.

Pliny the Elder, who also drew from Megasthenes' work, gives even larger numbers of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants.[84] Mudrarakshasa mentions that Chandragupta's army consisted of Sakas, Yavanas (Greeks), Kiratas, Kambojas, Parasikas and Bahlikas.[85]

Rule, succession and death

Chandragupta Maurya applied the statecraft and economic policies described in Chanakya's Arthashastra.[12][86][87] There are varying accounts in the historic, legendary and hagiographic literature of various Indian religions about Chandragupta, but these claims, state Allchin and Erdosy, are suspect. They add that the evidence is, however, not limited to texts, but include those discovered at archeological sites, epigraphy in the centuries that followed and the numismatic data, and "one cannot but be struck by the many close correspondences between the (Hindu) Arthashastra and the two other major sources the (Buddhist) Asokan inscriptions and (Greek) Megasthenes text".[88]

The Maurya rule was a structured administration, where Chandragupta had a council of ministers (amatya), the empire was organized into territories (janapada), centers of regional power were protected with forts (durga), state operations funded with treasury (kosa).[89]

Infrastructure projects

Ancient epigraphical evidence suggests that Chandragupta Maurya, under counsel from Chanakya, started and completed many irrigation reservoirs and networks across the Indian subcontinent in order to ensure food supplies for civilian population and the army, a practice continued by his dynastic successors.[88] Regional prosperity in agriculture was one of the required duties of his state officials.[90] Rudradaman inscriptions found in Gujarat mention that it repaired and enlarged, 400 years later, the irrigation infrastructure built by Chandragupta and enhanced by Asoka.[91]

Chandragupta's state also started mines, centers to produce goods, and networks for trading these goods. His rule developed land routes for goods transportation within the Indian subcontinent, disfavoring water transport. Chandragupta expanded "roads suitable for carts", preferring these over those narrow tracts that allowed only pack animals.[92]

According to Kaushik Roy, the Maurya dynasty rulers, beginning with Chandragupta, were "great road builders".[22] This was a tradition the Greek ambassador Megasthenes credited to Chandragupta with the completion of a thousand-mile-long highway connecting Chandragupta's capital Pataliputra in Bihar to Taxila in the northwest where he studied. The other major strategic road infrastructure credited to this tradition spread from Pataliputra in various directions: one connecting it to Nepal, Kapilavastu, Kalsi (now Dehradun), Sasaram (now Mirzapur), Kalinga (now Odisha), Andhra and Karnataka.[22] This infrastructure not only boosted trade and commerce, states Roy, but also helped move his armies rapidly and more efficiently than ever before.[22]

Chandragupta and his counsel Chanakya seeded weapon manufacturing centers, and kept it a monopoly of the state. However, the state encouraged competing private parties to operate mines and supply these centers.[98] They considered economic prosperity as essential to the pursuit of dharma (morality), adopting a policy of avoiding war with diplomacy, yet continuously preparing the army for war to defend its interests, and other ideas in the Arthashastra.[99][100]

Arts and architecture

The evidence of arts and architecture during Chandragupta's time is limited, predominantly texts such as those by Megasthenes and Kautilya's Arthashastra. The edict inscriptions and carvings on monumental pillars are attributed to his grandson Ashoka. The texts imply cities, public works and prosperous architecture, but the historicity of these is in question.[101]

Archeological discoveries in the modern age, such as Didarganj Yakshi discovered in 1917 buried beneath the banks of the River Ganges suggest exceptional artisanal accomplishment.[93][94] It has been dated to the 3rd century BCE by many scholars,[93][94] but later dates such as 2nd century BCE or the Kushan era (1st-4th century CE) have also been proposed. The competing theories are that the arts linked to Chandragupta Maurya's dynasty was learnt from the Greeks and West Asia in the years Alexander the Great waged war, while the other credits more ancient indigenous Indian tradition. According to Frederick Asher, "we cannot pretend to have definitive answers; and perhaps, as with most art, we must recognize that there is no single answer or explanation".[102]

Succession

After Chandragupta's renunciation, his son Bindusara succeeded as the Maurya Emperor. He maintained friendly relations with Greek governors in Asia and Egypt. Bindusara's son Ashoka became one of the most influential rulers in India's history due to his extension of the Empire to the entire Indian subcontinent as well as his role in the worldwide propagation of Buddhism.

Death

According to Jain accounts written more than 1,200 years later, such as those in Brihakathā kośa (931 CE) of Harishena, Bhadrabāhu charita (1450 CE) of Ratnanandi, Munivaṃsa bhyudaya (1680 CE) and Rajavali kathe, Chandragupta renounced his throne and followed Jain teacher Bhadrabahu to south India.[103][104][105] He is said to have lived as an ascetic at Shravanabelagola for several years before fasting to death, as per the Jain practice of sallekhana.[106]

Along with texts, several Jain monumental inscriptions dating from the 7th-15th century refer to Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta in conjunction. While this evidence is very late and anachronistic, there is no evidence to disprove that Chandragupta converted to Jainism in his later life. Mookerji, in his book, quotes Vincent Smith and concludes that conversion to Jain monk provides adequate explanation to Chandragupta's abdication and sudden exit at a relatively young age and at the height of his power. [106][107] The hill on which Chandragupta is stated in Jain tradition to have performed asceticism is now known as Chandragiri hill, and there is a temple named Chandragupta basadi there.[4]

The Hindu texts acknowledge the close relationship between the Jain community in Pataliputra and the royal court, and that the champion of Brahmanism Chanakya himself employed Jains as his emissaries. This also indirectly confirms the possible influence of Jain thought on Chandragupta.[108]

According to Kaushik Roy, Chandragupta renounced his wealth and power, crowned his son as his successor about 298 BCE, and died about 297 BCE.[36]

In popular culture

- D. L. Roy wrote a Bengali drama named Chandragupta based on the life of Chandragupta. The story of the play is loosely borrowed from the Puranas and the Greek history.[109]

- Chanakya's role in the formation of the Maurya Empire is the essence of a historical/spiritual novel The Courtesan and the Sadhu by Dr. Mysore N. Prakash.[110]

- The story of Chanakya and Chandragupta was made into a film in Telugu in 1977 titled Chanakya Chandragupta. Akkineni Nageswara Rao played the role of Chanakya, while N. T. Rama Rao portrayed Chandragupta.[111]

- The television series Chanakya is an account of the life and times of Chanakya, based on the play "Mudra Rakshasa" (The Signet Ring of "Rakshasa").[112]

- In 2011, a television series called Chandragupta Maurya was telecast on Imagine TV in which the titular role was played by Rushiraj Pawar & Ashish Sharma.[113][114][115]

- In 2016, television series Chandra Nandini, a fictionalized version of Chandragupta and fictional character Nandini's romance saga. In real life, Chandragupta married only twice, first to Durdhara who died while giving birth to Bindusara and 17 years after his wife's death to Helen, daughter of Seleucus I Nicator in a peace treaty. Fictional Nandini as per show is described as daughter of Mahapadma Nanda which is completely untrue as there exists no evidence in any historical texts. The role of Chandragupta Maurya is played by actor Rajat Tokas [116]

- The Indian Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp honouring Chandragupta Maurya in 2001.[117]

- He is a leader of the Indian civilization in the Civilization VI expansion Rise and Fall.[118]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Aria (modern Herat) "has been wrongly included in the list of ceded satrapies by some scholars [...] on the basis of wrong assessments of the passage of Strabo [...] and a statement by Pliny."[66] Seleucus "must [...] have held Aria", and furthermore, his "son Antiochos was active there fifteen years later." (Grainger, John D. 1990, 2014. Seleukos Nikator: Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom. Routledge. p. 109).

References

- ↑ Radhakumud Mookerji (1966), Chandragupta Maurya and His Times, p.40: "A smaller hill at Sravana Belgola is called Chandragiri, because Chandragupta lived and performed his penance there. On the same hill is [...] an ancient temple called Chandragupta-Basti, because it was erected by Chandragupta [according to Jain tradition]. Moreover, the facade of this basti or temple which is in the form of a perforated screen, contains 90 sculptured scenes depicting events in the lives of Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chandragupta Maurya, EMPEROR OF INDIA Archived 8 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1 2 Upinder Singh 2016, p. 331.

- 1 2 Mookerji 1988, p. 40.

- ↑

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 330.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 40-41.

- 1 2 Roy 2012, p. 62.

- ↑ Boesche, Roger. "Kautilya's Arthasastra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India." The Journal of Military History, vol. 67 no. 1, 2003, pp. 9-37. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/jmh.2003.0006

- ↑ Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. xxviii. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 59-65.

- 1 2 Boesche 2003, p. 7-18.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 2-14, 229-235.

- 1 2 Thapar 2004, p. 177.

- ↑ Burton Stein (4 February 2010). A History of India. John Wiley & Sons. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 1-4.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 1.

- ↑ Vaughn, Bruce (2004). "Indian Geopolitics, the United States and Evolving Correlates of Power in Asia". Geopolitics. 9 (2): 440–459 [442]. doi:10.1080/14650040490442944.

- ↑ Goetz, H. (1955). "Early Indian Sculptures from Nepal". Artibus Asiae. 18 (1): 61–74. doi:10.2307/3248838. JSTOR 3248838.

- 1 2 Mookerji 1988, pp. 13-18.

- ↑ F. R. Allchin & George Erdosy 1995, pp. 187-195.

- 1 2 3 4 Roy 2012, pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Gananath Obeyesekere (1980). Wendy Doniger, ed. Karma and Rebirth in Classical Indian Traditions. University of California Press. pp. 137–139 with footnote 3. ISBN 978-0-520-03923-0.

- ↑ Henry Albinski (1958), The Place of the Emperor Asoka in Ancient Indian Political Thought Archived 14 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Midwest Journal of Political Science, Vol. 2, No. 1, pages 62-75

- ↑ Mookerji, Radhakumud (1962). Aśoka (3rd Revised., repr ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (reprint 1995). pp. 60–64. ISBN 978-81208-058-28.

- ↑ Jerry Bentley (1993), Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times, Oxford University Press, pages 44-46

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 3-14.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 5-16.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 1-6.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 3.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Kosmin 2014, p. 32.

- 1 2 Mookerji 1988, pp. 13-14.

- 1 2 3 Mookerji 1988, pp. 7-13.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roy 2012, pp. 61-62.

- 1 2 Mookerji 1988, pp. 15-18.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 18-23, 53-54, 140-141.

- ↑ Modelski, George (1964). "Kautilya: Foreign Policy and International System in the Ancient Hindu World". American Political Science Review. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 58 (03): 549–560. doi:10.2307/1953131.

- 1 2 Eggermont, Pierre Herman Leonard (1975). Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia. Peeters Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 9789061860372.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Alexander, 62-9

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 22-27.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 2, 25-29.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 31-33.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 33-35.

- ↑ Romila Thapar (2013). The Past Before Us. Harvard University Press. pp. 362–364. ISBN 978-0-674-72651-2.

- 1 2 R.K. Sen (1895). "Origin of the Maurya of Magadha and of Chanakya". Journal of the Buddhist Text Society of India. The Society. pp. 26–32.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 28-33.

- ↑ John Marshall Taxila, p. 18, and al.

- ↑ Sastri 1988, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 Mookerji 1988, p. 6.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 47-53, 79-85.

- ↑ Roy 2015, pp. 46-50.

- 1 2 Bhattacharyya 1977, p. 8.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 165-166.

- ↑ Roy 2012, pp. 27, 61-62.

- ↑ R.G. Grant: Commanders, Penguin (2010). pg. 49

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. A Historical Atlas of South Asia, 2nd ed. (University of Minnesota, 1992), Plate III.B.4b (p.18) and Plate XIV.1a-c (p.145)

- ↑ Modelski, George (1964). "Kautilya: Foreign Policy and International System in the Ancient Hindu World". American Political Science Review. Cambridge University Press. 58 (03): 549–560. doi:10.2307/1953131. ISSN 0003-0554. ; Quote: "Kautilya is believed to have been Chanakya, a Brahmin who served as Chief Minister to Chandragupta (321–296 B.C.), the founder of the Mauryan Empire."

- ↑ Thomas R. Trautmann (2012). Arthashastra: The Science of Wealth. Penguin. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-670-08527-9. , Quote: "We can confirm from other texts that Kautilya (or Kautalya - the name varies) is a Brahmin gotra name. (...) This Kautilya, author of Arthashastra, is identified with Chanakya, minister to the first Mauryan king, Chandragupta, and depicted in stories as the brains behind Chandragupta's takeover of the empire of the Nandas in about 321 BCE. The adventures of Chanakya and Chandragupta are told in a cycle of tales preserved in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain books."

- ↑ Boesche 2003, p. 9-37.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 36.

- ↑ Kosmin 2014, p. 34.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 36-37, 105.

- ↑ Walter Eugene, Clark (1919). "The Importance of Hellenism from the Point of View of Indic-Philology". Classical Philology. 14 (4): 297–313. doi:10.1086/360246.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee 1996, p. 594.

- 1 2 Mookerji 1988, p. 37.

- ↑ History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55 Archived 3 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Strabo 15.2.1(9)".

- ↑ Barua, Pradeep. The State at War in South Asia Archived 5 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine.. Vol. 2. U of Nebraska Press, 2005. pp13-15 via Project MUSE (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 Thomas McEvilley, "The Shape of Ancient Thought", Allworth Press, New York, 2002, ISBN 1581152035, p.367

- 1 2 Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Krishna Chandra Sagar, Northern Book Centre, 1992, p.83

- ↑ The country is transliterated as "Pausasa" in the online translation: Pratisarga Parva p.18 Archived 23 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. and in Encyclopaedia of Indian Traditions and Cultural Heritage, Anmol Publications, 2009, p.18; and "Paursa" in the original Sanskrit of the first two verses given in Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Krishna Chandra Sagar, Northern Book Centre, 1992, p.83:

- ↑ Translation given in: Encyclopaedia of Indian Traditions and Cultural Heritage, Anmol Publications, 2009, p.18. Also online translation: Pratisarga Parva p.18 Archived 23 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Original Sanskrit of the first two verses given in Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Krishna Chandra Sagar, Northern Book Centre, 1992, p.83: "Chandragupta Sutah Paursadhipateh Sutam. Suluvasya Tathodwahya Yavani Baudhtatapar".

- ↑ India, the Ancient Past, Burjor Avari, p. 106-107

- ↑ Majumdar 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ Tarn, W. W. (1940). "Two Notes on Seleucid History: 1. Seleucus' 500 Elephants, 2. Tarmita". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 60: 84–94. doi:10.2307/626263. JSTOR 626263.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 38.

- ↑ "Problem while searching in The Literature Collection". digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- ↑ Sastri 1988, p. 18.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 41-42.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 75, 164-172.

- ↑ "Project South Asia". 28 May 2006. Archived from the original on 28 May 2006.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 27.

- ↑ MV Krishna Rao (1958, Reprinted 1979), Studies in Kautilya, 2nd Edition, OCLC 551238868, ISBN 978-8121502429, pages 13-14, 231-233

- ↑ Olivelle 2013, pp. 31-38.

- 1 2 F. R. Allchin & George Erdosy 1995, pp. 187-194.

- ↑ F. R. Allchin & George Erdosy 1995, pp. 189-192.

- ↑ F. R. Allchin & George Erdosy 1995, pp. 192-194.

- ↑ F. R. Allchin & George Erdosy 1995, p. 189.

- ↑ F. R. Allchin & George Erdosy 1995, pp. 194-195.

- 1 2 3 Tapati Guha-Thakurta (2006). Partha Chatterjee and Anjan Ghosh, ed. History and the Present. Anthem. pp. 51–53, 58–59. ISBN 978-1-84331-224-6.

- 1 2 3 Manohar Laxman Varadpande (2006). Woman in Indian Sculpture. Abhinav Publications. pp. 32–34 with Figure 11. ISBN 978-81-7017-474-5.

- ↑ "A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century" by Upinder Singh, Pearson Education India, 2008 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ ""Ayodhya, Archaeology After Demolition: A Critique of the "new" and "fresh" Discoveries", by Dhaneshwar Mandal, Orient Blackswan, 2003, p.46 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ "A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture" by Deborah S. Hutton, John Wiley & Sons, 2015, p.435 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ Roy 2012, pp. 63-64.

- ↑ Roy 2012, pp. 64-68.

- ↑ Olivelle 2013, pp. 49-51, 99-108, 277-294, 349-356, 373-382.

- ↑ Thomas Harrison (2009). The Great Empires of the Ancient World. Getty Publications. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-0-89236-987-4.

- ↑ Frederick Asher (2015). Rebecca M. Brown and Deborah S. Hutton, ed. A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 421–423. ISBN 978-1-119-01953-4.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Samuel 2010, pp. 60.

- ↑ Thapar 2004, p. 178.

- 1 2 Mookerji 1988, pp. 39-41.

- ↑ Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 41.

- ↑ Ghosh, Ajit Kumar (2001). Dwijendralal Ray. Makers of Indian Literature (1st ed.). New Delhi: Sahitye Akademi. pp. 44–46. ISBN 81-260-1227-7.

- ↑ The Courtesan and the Sadhu, A Novel about Maya, Dharma, and God, October 2008, Dharma Vision LLC., ISBN 978-0-9818237-0-6, Library of Congress Control Number: 2008934274

- ↑ "Chanakya Chandragupta (1977)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ "Television". The Indian Express. 8 September 1991.

- ↑ "Chandragupta Maurya comes to small screen". Zee News. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ "Chandragupta Maurya on Sony TV?". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016.

- ↑ TV, Imagine. "Channel". TV Channel. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- ↑ "Real truth behind Chandragupta's birth, his first love Durdhara and journey to becoming the Mauryan King". 17 October 2016. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017.

- ↑ Commemorative postage stamp on Chandragupta Maurya Archived 27 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Press Information Bureau, Govt. of India

- ↑ "Civilization® VI – The Official Site | News | CIVILIZATION VI: RISE AND FALL - CHANDRAGUPTA LEADS INDIA". civilization.com. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

Sources

- F. R. Allchin; George Erdosy (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2.

- Bhattacharyya, Pranab Kumar (1977), Historical Geography of Madhyapradesh from Early Records, Motilal Banarsidass

- Boesche, Roger (January 2003), "Kautilya's Arthaśāstra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India" (PDF), The Journal of Military History, 67 (1): 9, doi:10.1353/jmh.2003.0006, ISSN 0899-3718

- Boesche, Roger (2002). The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0401-2.

- Kangle, R. P. (1969). Kautilya Arthashastra, 3 vols. Motilal Banarsidass (Reprinted 2010). ISBN 978-8120800410.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004), A History of India (4th ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-15481-2

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (2003) [1952], Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0436-8

- Mabbett, I. W. (April 1964). "The Date of the Arthaśāstra". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 84 (2): 162–169. doi:10.2307/597102. JSTOR 597102.

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3

- Olivelle, Patrick (2013), King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India: Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra, Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199891825

- Rangarajan, L.N. (1992). Kautilya: The Arthashastra. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044603-6.

- Raychaudhuri, H. C.; Mukherjee, B. N. (1996), Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty, Oxford University Press

- Roy, Kaushik (2012), Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-01736-8

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India–1500BCE to 1740CE, Routledge

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta, ed. (1988) [1967], Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0465-1

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Smith, Vincent Arthur (1998). Ashoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1303-1.

- Thapar, Romila (2004) [first published by Penguin in 2002], Early India: From the Origins to A.D. 1300, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8

Further reading

| Library resources about Chandragupta Maurya |

- Habib, Irfan. and Jha, Vivekanand. Mauryan India: A People's History of India, New Delhi, Tulika Books, 2016

- Bongard-Levin, G. M. Mauryan India (Stosius Inc./Advent Books Division May 1986) ISBN 0-86590-826-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chandragupta Maurya. |

- Mudrarakshas, Bharatendu Harischandra (1925, in Hindi)

- Indica by Megasthenes

| Preceded by Nanda Empire |

Mauryan Emperor 322–298 BC |

Succeeded by Bindusara |