Torres Strait Islanders

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 48,005 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Australia | |

| Languages | |

| Torres Strait Island languages | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Aboriginal Australians, Papuans, Melanesians |

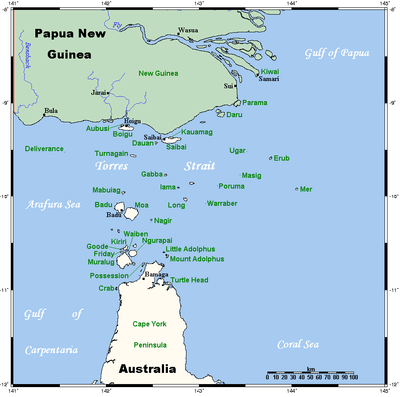

Torres Strait Islanders (/ˈtɒrɪs-/[1] ) are the indigenous people of the Torres Strait Islands, part of Queensland, Australia. They are distinct from the Aboriginal people of the rest of Australia, and are generally referred to separately. There are also two Torres Strait Islander communities on the nearby coast of the mainland at Bamaga and Seisia.

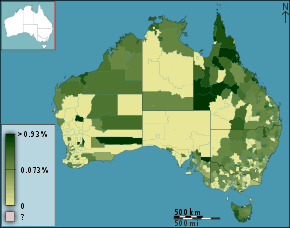

Population

There are 6,800 Torres Strait Islanders who live in the area of the Torres Strait, and 42,000 others who live outside the area, mostly in the north of Queensland, particularly in Townsville and Cairns.[2]

Culture

The indigenous people of the Torres Strait have a distinct culture which has slight variants on the different islands where they live. They are a seafaring people, and they trade with people of Papua New Guinea. The culture is complex, with some Australian elements, some Papuan elements, and Austronesian elements, just like the languages. The Islanders seem to have been the dominant culture for many centuries, and neighbouring Aboriginal and Papuan cultures show some Island influence in religious ceremonies and the like.

Archaeological, linguistic and folk history evidence suggests that the core of Island culture is Papuo-Austronesian. Unlike the indigenous peoples of mainland Australia, but like those of neighbouring Papua, some communities of islanders are agriculturalists though others (notably in the central islands) are not. All communities also engage in hunting and gathering. Dugong, turtle, crayfish, crabs, shellfish, reef fish and wild fruits and vegetables were traditionally hunted and collected and remain an important part of their subsistence lifestyle.[3] Traditional foods play an important role in ceremonies and celebrations even when they do not live on the islands. Dugong and turtle hunting as well as fishing are seen as a way of continuing the Islander tradition of being closely associated with the sea.[3]

Their more recent, post-colonization history has seen new cultural influences, most notably the place of Christianity (particularly of the Baptist and Anglican strains) which caused major shifts in cultural paradigms, as well as subtler additions through the influence of Polynesians, particularly Samoan and Rotuman sea workers and missionaries who worked in the area in the 19th Century.

Art

The Torres Strait Islands, particularly since the 1970s, have produced some outstanding and successful artists, in particular printmakers, sculptors and mask-makers, and dancers. The Islands have a long tradition of woodcarving, creating masks and drums, and carving decorative features on these and other items for ceremonial use. The modern and portable art form of printmaking, particularly linocut and etching has been a natural progression for island artists many of whom grew up learning carving, especially in wood.

The College of Technical and Further Education on Thursday Island was a starting point for young islanders to pursue studies in art. Many went on to further art studies, especially in printmaking, initially in Cairns and later at the Australian National University in what is now the School of Art and Design, then called the Canberra Institute of the Arts. Linocut prints in particular are now a favoured medium, and striking prints are produced with black ink on white paper. Prints tell the stories of spiritual beings, island life, the environment, and the range of creatures central to Torres Strait Island life. The prints often incorporate extensive background patterning, some of which has been rediscovered after research in anthropological collections in overseas and local museums. Artists such as Laurie Nona, Brian Robinson, Alick Tipoti, Dennis Nona, Billy Missi, David Bosun, and more recently Glen Mackie, Joemen Nona, Daniel O'Shane and Tommy Pau produce vibrant and energetic prints which are held in local and overseas collections.

At around the same time as these artists were beginning studies in art, there was underway a significant re-connection to traditional myths and legends. Many of these had been all but forgotten when Margaret Lawrie's significant publications, Myths and Legends of the Torres Strait and Tales from the Torres Strait were published in 1970 and 1972 respectively.[4][5] While some of these stories had been written down by Alfred Cort Haddon after his anthropological expedition to the Torres Strait in 1898,[6] in the years after his publications up to perhaps World War 2, dispersal of the islanders and lack of any further written records meant there was a real danger that the material culture of the islands was being lost. The artists found a new direction in interpreting and presenting these traditional stories in prints. Prints not only served as a vehicle for interpreting stories to their own people, but have found a new and increasingly large Australian and international audience with their striking imagery. Artists have produced prints that are up to 8 metres in length, foregrounding a narrative with exquisitely detailed patterned backgrounds. The imagery fuses the myths and legends with the maritime perspective of the Torres Strait Islands, and depicts spirit figures and human elements, in the sea, on the land and under the stars, surrounded by the dugongs, turtles, fish, crocodiles and birds that are part of the islands' environment.

Not all Torres Strait Islander printmakers work exclusively in myths and legends. Some include a range of contemporary iconography, including, western art references and pop culture images such as comic book characters, either to add depth of meaning to or comparisons with local cultural chronicling. Others represent day to day life and the environment, such as the dugong and her calf swimming together, or turtles or jellyfish with traditional patterning on their bodies or as background.

Several of these artists also produce sculptures, and carved and decorated masks and headdresses. Dance performances have been a constant expression of Torres Strait Islands culture throughout the twentieth century. Head decorations, masks, costumes and mechanical dance machines are created to use in traditional ceremonies and performances. Modern day masks can be simple carved faces or more elaborate decorated pieces. Headdresses or dhari (see the Torres Strait Islands flag, above right) and dance machines (hand held mechanical objects) constructed of a mix of traditional and contemporary materials, bring colour and movement to performances. Like much of the art of the Torres Strait, dharis and masks are essentially spiritual, but have taken on the ability to reflect stories and historical and contemporary events, using modern materials of metal and plywood but also more traditional feathers, human hair, bamboo, bean pods and shell. Masks, drumming and chanting are often combined with dance performances for exhibitions such as: Alick Tipoti's Zugubal. Ancestral Spirits at the Cairns Regional Gallery in July 2015.

Artists and artworks are assisted by several local art centres in the Torres Strait Islands. These centres provide support and training for artists and future artists, show examples of current work, programs and projects, detail artist biographies and list exhibitions. Links to these centres are provided below.

Prominent among these is wame (alt. wameya), many different string figures[7][8][9] (a particular string figure game played by two or more participants that generates several string figures is familiar to people of many cultures under the name Cat's cradle), some extremely elaborate and beautiful, and 'string catches' (games in which strings are wrapped around fingers then removed quickly with a single pull).

Languages

The Western-central Torres Strait Language, or Kalaw Lagaw Ya, is spoken on the southwestern, western, northern and central islands. It is an Australian Aboriginal language. Meriam Mir is spoken on the eastern islands. It is one of the Eastern Trans-Fly languages, otherwise spoken in Papua New Guinea.[10]

Administration

The Torres Strait Islanders have been administered by a system of elected councils.[11] This is a system based partly on traditional pre-Christian local government and partly on the introduced mission management system.[11]

Notable Torres Strait Islanders

- Patty Mills - NBA player for the San Antonio Spurs

- Sam Powell-Pepper – Australian Football League player for Port Adelaide[12]

- Albert Proud – Australian Football League player for Brisbane Lions[13]

- Cynthia Lui – the first Torres Strait Islander elected to the Parliament of Queensland[14]

- Christine Anu - an Australian pop singer and actress. She gained popularity with the release of her song "My Island Home". Anu has been nominated for 17 ARIA Awards.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ "Torres Strait. Oxford Dictionary Online". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ↑ "Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples". Australia Now. Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- 1 2 Smyth, Dermot (2002). "Appendix B: The Indigenous Sector: An Anthropological Perspective". In Hundloe, Tor. Valuing Fisheries. University of Queensland Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 0702233293. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Lawrie, Margaret Elizabeth (1970). Myths and Legends of the Torres Strait/collected and translated by Margaret Lawrie. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

- ↑ Lawrie, Margaret Elizabeth (1972). Tales from Torres Strait. St Lucia Qld: University of Queensland Press.

- ↑ Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits (1898); Hodes, Jeremy. Index to the Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits; Haddon, Alfred C. (Alfred Cort), 1855–1940; Ray, Sidney Herbert, 1858–1939. Linguistics (1901), Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits, University Press

- ↑ Brij V. Lal; Kate Fortune, eds. (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 456. ISBN 978-0-8248-2265-1. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ Alfred Cort Haddon, along with one of his daughters, the pioneers in the modern study of Torres Strait string figures

- ↑ A string figure bibliography including examples from Torres Strait.

- ↑ "Indigenous Fact Sheet: Torres Strait Islanders" (PDF). Australian Government, Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- 1 2 Jeremy Beckett (1990). Torres Strait Islanders: Custom and Colonialism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-521-37862-8. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ Resilience the driving force behind Sam Powell-Pepper's draft bid

- ↑ AFL Record. Round 9,2009. Slattery Publishing. pg 75.

- ↑ Moore, Tony (28 November 2017). "Labor one seat closer as first Torres Strait Islander woman elected to Parliament". Brisbane Times. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ↑ "History: Winners by Artist: Christine Anu". ARIA Awards. Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

External links

| Library resources about Torres Strait Islanders |

- Torres Strait Regional Authority

- Church of Torres Strait

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders' virtual books – held by the State Library of Queensland.

- Contemporary stories by and about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Social Justice Reports 1993–2015 and Native Title Reports 1994–2015 for more information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs.

- Torres Strait Islander Art from Badu Island

- Art of Mua Island Torres Strait

- Darnley Island Arts Centre

- Alick Tipoti artist

- Gab Titui Cultural Centre