Local government in New Zealand

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of New Zealand |

| Constitution |

|

|

|

|

Related topics |

|

|

New Zealand is a unitary state rather than a federation—regions are created by the authority of the central government, rather than the central government being created by the authority of the regions. Local government in New Zealand has only the powers conferred upon it by Parliament. These powers have traditionally been distinctly fewer than in some other countries. For example, police and education are run by central government, while the provision of low-cost housing is optional for local councils.

As defined in the Local Government Act 2002, the purpose of local government is:

- to enable democratic local decision-making and action by, and on behalf of, communities; and

- to meet the current and future needs of communities for good-quality local infrastructure, local public services and performance of regulatory functions in a way that is most cost-effective for households and businesses.[1]

As of 2017 there are seventy-eight local authorities (regions, cities and districts) representing all areas of New Zealand.[2]

History

The early European settlers divided New Zealand into provinces. These provinces were largely autonomous, each with an elected council and an elected chief official, called a superintendent.[3] Provinces were abolished in 1876 so that government could be centralised, for financial reasons.[4] As a result, New Zealand has no separately represented subnational entities such as provinces, states or territories, apart from local government. The provinces are remembered in regional public holidays[5] and sporting rivalries.[6]

From 1876 onwards, local authorities have distributed functions varying according to the local arrangement. A system of counties similar to other countries' systems was instituted, lasting with little change (except mergers and other localised boundary adjustments) until 1989. In the 1989 reforms, the central government completely reorganised local government, implementing the current two-tier structure of regions and territorial authorities constituted under the Local Government Act 2002.[1] The Resource Management Act 1991 replaced the Town and Country Planning Act as the main planning legislation for local government.[7]

Auckland Council is the newest local authority. It was created on 1 November 2010, combining the functions of the existing regional council and the region's seven previous city and district councils into one "super-city".[8][9][10] It brings the number of unitary authorities in New Zealand to five.

Structure

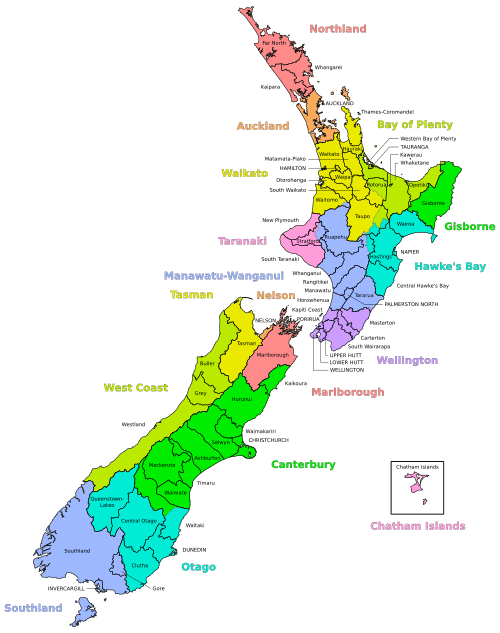

New Zealand has two tiers of local government. The top tier consists of regional councils, of which there are eleven.[2] The second tier consists of territorial authorities, of which there are sixty-seven.[2] The territorial authorities comprise thirteen city councils (including Auckland Council), fifty-three district councils and Chatham Islands Council.[11][12] Five territorial authorities are also unitary authorities, which perform the functions of a regional council in addition to those of a territorial authority. Most territorial authorities are wholly within one region, but there are a few that cross regional boundaries. In each territorial authority there are commonly several community boards, which form the lowest and weakest arm of local government.[13] The outlying Chatham Islands have a council with its own special legislation, constituted with powers similar to those of a unitary authority.[14]

Each of the regions and territorial authorities is governed by a council, which is directly elected by the residents of that region, district or city. Each council may use a system chosen by the outgoing council (after public consultation), either the bloc vote (viz. first past the post in multi-member constituencies) or single transferable vote.[15]

The external boundaries of an authority can be changed by an Order in Council or notices in the New Zealand Gazette.[16]

Local government jurisdictions

Regions

Regional councils all use a constituency system for elections, and the elected members elect one of their number to be chairperson. Regional councils are funded through rates, subsidies from central government, income from trading, and user charges for certain public services.[17] Councils set their own levels of rates, though the mechanism for collecting it usually involves channelling through the territorial authority collection system.[18] Regional council duties include:

- environmental management, particularly air and water quality and catchment control under the Resource Management Act 1991.[7]

- regional aspects of civil defence.[12]

- transportation planning and contracting of subsidised public passenger transport.[19]

Cities and districts

The territorial authorities consist of thirteen city councils, fifty-three district councils and one special council for the Chatham Islands.[11] A city is defined in the Local Government Act 2002 as an urban area with 50,000 residents.[1] A district council serves a combination of rural and urban communities. Each generally has a ward system of election, but an additional councillor is the mayor, who is elected at large and chairs the council.[1] They too set their own levels of rates.[18] Territorial authorities manage the most direct government services, such as water supply and sanitation, public transport, libraries, museums and recreational facilities.[19]

The territorial authorities may delegate powers to local community boards. The boundaries of community boards may be reviewed before each triennial local government election; this is provided for in the Local Electoral Act 2001.[20] These boards, instituted at the behest of either local citizens or territorial authorities, advocate community views but cannot levy taxes, appoint staff, or own property.[12]

District health boards

New Zealand's health sector was restructured several times during the 20th century. The most recent restructuring occurred in 2001, with new legislation creating twenty-one district health boards (DHBs). These boards are responsible for the oversight of health and disability services within their communities.[21] Seven members of each district health board are directly elected by residents of their area using the single transferable vote system. In addition, the Minister of Health may appoint up to four members. There are currently twenty DHBs.[21]

Māori wards and constituencies

The Local Electoral Act 2001's Section 19Z introduced provisions allowing territorial authorities and regional councils to introduce Māori wards in cities and districts and constituencies in regions for electoral purposes.[22] These wards and constituencies are modeled after the Māori electorates in the New Zealand Parliament and are open to those registered on the Māori electoral roll. Māori wards and constituencies can be established through three different processes:

- A council may resolve to establish Māori wards or constituencies. If so, a poll on the issue must be held if 5 percent of the electors of the city, district or region request it.

- A council may decide to hold a poll on whether or not there should be Māori wards or constituencies.

- A poll on whether there should be Māori wards or constituencies must be held if requested by a petition signed by 5 percent of the electors of the city, district or region.

The results of these polls are binding for at least two local body elections.[23]

History

In 2001, the Fifth Labour Government introduced the Bay of Plenty Regional Council (Maori Constituency Empowering) Act 2001, which created a Māori ward on Environment Bay of Plenty. Three Māori wards were also established on the Bay of Plenty Regional Council called Kohi Maori, Mauao Maori (which covers Tauranga and Western Bay of Plenty), and Okurei Maori . While this legislation was supported by the Labour, Alliance, and Green parties, it was opposed by the opposition National Party, New Zealand First leader Winston Peters, and the libertarian ACT Party.[24][25][26]

In late October 2011, the Waikato Regional Council voted by 14 to 2 to establish two Māori seats in preparation for the 2013 local body elections.[27]

In 2014, the Mayor of New Plymouth Andrew Judd proposed introducing a Māori ward in the New Plymouth District Council. The Council's division was defeated in a 2015 referendum by a margin of 83% to 17% triggered by a 4,000 signature petition organised by local resident Hugh Johnson. A local racist backlash led Judd not to run for a second term during the 2016 local body elections[28][29] In April 2016, Māori Party co-leader Te Ururoa Flavell presented a petition to the New Zealand Parliament on behalf of Judd advocating the establishment of mandatory Māori wards on every district council in New Zealand.[30]

In late June 2017, Green Member of Parliament (MP) Marama Davidson tried to introduce a member's bill to amend the Local Electoral Act 2001 to establish Māori wards and constituencies while bypassing the requirement for polls. This bill was defeated during its first reading.[31][32] In late October 2017, the Palmerston North City Council voted to establish a Māori ward.[33] The following month, four other local government bodies—the Kaikoura District Council, the Whakatane District Council, the Manawatu District Council, and the Western Bay of Plenty District Councils—also voted in favour of introducing special Māori wards. This was welcomed by the Labour Minister for Local Government Nanaia Mahuta.[34][35][36][37]

In response, the "anti-Maori rights" lobby group Hobson's Pledge organized several petitions in Palmerston North and those districts to call for local referendums on the matter of introducing Māori wards and constituencies; taking advantage of the referendum clause in the 2001 Local Electoral Act.[38][39] Between later April and mid–May 2018, local referendums were held in Palmerston North and the four districts to decide if their councils should have Māori wards.[40][41][42] During those referendums, Māori wards were rejected by voters in Palmerston North (68.8%), Western Bay of Plenty (78.2%), Whakatane (56.4%), Manawatu (77%), and Kaikoura (55%) on 19 May 2018; with the average voter turnout in those polls being about 40%.[43][44][45][46]

The rejection of Māori wards was welcomed by Hobson's Pledge leader and former National Party leader Don Brash and conservative broadcaster Mike Hosking.[47][48] By contrast, the referendum results were met with dismay by Whakatāne Mayor Tony Bonne and several Māori leaders including Labour MPs Willie Jackson and Tamati Coffey, former Māori Party co-leader Te Ururoa Flavell, Bay of Plenty resident and activist Toni Boynton, and left-wing advocacy group ActionStation national director Laura O'Connell Rapira.[49][46][50] In response, ActionStation organised a petition calling on Local Government Minister Nanaia Mahuta to amend the Local Electoral Act's provisions on Māori wards.[51]

See also

- Local Government New Zealand, represents the interests of local government bodies

- New Zealand Local Government, a monthly trade magazine published since 1964

- New Zealand local government and human rights

- Realm of New Zealand, including associated states and dependencies

- New Zealand outlying islands

- Local Government Act 1974

- Local Government Act 2002

- Community Board (New Zealand)

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Local Government Act 2002 No 84 (as at 01 March 2016), Public Act – New Zealand Legislation". Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Local government in New Zealand". localcouncils.govt.nz. Department of Internal Affairs.

- ↑ McKinnon, Malcolm (20 June 2012). "Colonial and provincial government – Colony and provinces, 1852 to 1863". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ McKinnon, Malcolm (20 June 2012). "Colonial and provincial government – Julius Vogel and the abolition of provincial government". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Holidays and anniversary dates (2017–2020)". Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Overview – regional rugby". nzhistory.govt.nz. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Resource Management Act 1991 No 69 (as at 13 December 2016), Public Act Contents – New Zealand Legislation". Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ Thompson, Wayne (28 March 2009). "Super-city tipped to save $113m a year". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ↑ "Background information". Auckland Council. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Local Government (Auckland Council) Act 2009 No 32 (as at 10 May 2016), Public Act Contents – New Zealand Legislation". Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Council Profiles by Type". Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 Gillespie, Carol Ann. New Zealand. Infobase Publishing. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9781438105246. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Glossary". localcouncils.govt.nz. Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Chatham Islands Council Act 1995 No 41 (as at 01 July 2013), Public Act Contents – New Zealand Legislation". Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "2007 Local Elections". Elections New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Local government boundaries". Local Government Commission. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ↑ Derby, Mark (17 February 2015). "Local and regional government". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Local Government (Rating) Act 2002". localcouncils.govt.nz. Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Your Local Council" (PDF). localcouncils.govt.nz. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Local Electoral Act 2001 No 35 (as at 26 March 2015), Public Act Contents – New Zealand Legislation". Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- 1 2 "District health boards". Ministry of Health. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Local Electoral Act 2001 Section 19Z". New Zealand Legislation. Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "Voting and becoming a councillor". localcouncils.govt.nz. Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Janine Hayward (2002). The Treaty Challenge: Local Government and Maori (PDF) (Report). Crown Forestry Rental Trust. p. 23-32. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "Maori seats". Bay of Plenty Regional Council. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Wood, Ray (13 May 2018). "The truth about Maori wards". SunLive. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "Council votes to establish Maori seats". Waikato Regional Council. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Utiger, Taryn (30 September 2016). "New Plymouth mayor Andrew Judd looks back on his three years as a 'recovering racist'". Taranaki Daily News. Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Utiger, Taryn (15 May 2015). "Resounding no to a Maori ward for New Plymouth district". Taranaki Daily News. Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Backhouse, Matthew (10 April 2016). "Maori Party calls for law change". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Davidson, Marama. "Local Electoral (Equitable Process for Establishing Māori Wards and Māori Constituencies) Amendment Bill". New Zealand Parliament. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Davidson, Marama. "Local Electoral (Equitable Process for Establishing Māori Wards and Māori Constituencies) Amendment Bill". New Zealand Legislation. Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Rankin, Janine (24 October 2017). "Palmerston North City councillors vote for Māori seats". Manawatu Standard. Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "The facts about Maori representation at Council" (PDF). Kaikoura District Council. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "Whakatane votes for Māori wards". Newshub. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Kilmister, Sam (16 November 2017). "Manawatū District Council guarantees Māori seats at next election". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "Western BOP Council votes for Māori ward". Radio New Zealand. 21 November 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "Petitions to demand votes on separate Maori wards". Hobson's Pledge. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Timutimu, Ripeka (30 April 2018). "Fight for Māori wards like Nazi Germany – Hobson's Pledge supporter". Māori Television. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Tuckey, Karoline (25 April 2018). "Māori wards for Manawatū councils put to the vote in referendums". Manawatu Standard. Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "Referendum hurdle for Maori wards". Radio Waatea. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "Western Bay Maori wards referendum going ahead". Bay of Plenty Times; New Zealand Herald. 21 February 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Hurihanganui, Te Aniwa (22 May 2018). "Rejection of Māori wards: 'This is wrong'". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "Mayor 'gutted' after public votes against Māori wards". Radio New Zealand. 19 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Kilmister, Sam; Rankin, Janine (15 May 2018). "Manawatū Māori wards vote a resounding 'no'". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- 1 2 Lee, Moana Makapelu (21 May 2018). "Four districts reject Maori wards". Māori Television. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Butler, Michael. "Brash: Respect 'No' votes on Maori wards". Hobson's Pledge. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Hosking, Mike (21 May 2018). "Mike Hosking: Good riddance to Māori ward nonsense". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "Hobson's Pledge using 'scare tactics' to block Māori Wards – Te Ururoa Flavell". Newshub. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ O'Connell Rapira, Laura (14 May 2018). "Why we need Māori wards". The Spinoff. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "Change the discriminatory law that enabled the Māori wards referenda". ActionStation. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

External links

- Local Councils – Official website (maintained by the Department of Internal Affairs)

- Envirolink – a regional council driven funding scheme

- Relevant legislation – legislation.govt.nz

Administrative divisions of the Realm of New Zealand | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | |||||||||||

| Regions | 11 non-unitary regions | 5 unitary regions | Chatham Islands | Outlying islands outside any regional authority (the Kermadec Islands, Three Kings Islands, and Subantarctic Islands) |

Ross Dependency | 15 islands | 14 villages | ||||

| Territorial authorities | 13 cities and 53 districts | ||||||||||

| Notes | Some districts lie in more than one region | These combine the regional and the territorial authority levels in one | Special territorial authority | The outlying Solander Islands form part of the Southland Region | New Zealand's Antarctic territory | Non-self-governing territory of New Zealand | States in free association with New Zealand | ||||