Minority language

A minority language is a language spoken by a minority of the population of a territory. Such people are termed linguistic minorities or language minorities. With a total number of 193 sovereign states recognized internationally (as of 2008)[1] and an estimated number of roughly 5,000 to 7,000 languages spoken worldwide,[2] it follows that the vast majority of languages are minority languages in every country in which they are spoken. Some minority languages are simultaneously also official languages, including the Irish language in Ireland. Likewise, some national languages are often considered minority languages, insofar as they are the national language of a stateless nation.

Law and international politics

Europe

- Definition

For the purposes of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages:

- "regional or minority languages" means languages that are:

- traditionally used within a given territory of a State by nationals of that State who form a group numerically smaller than the rest of the State's population; and

- different from the official language(s) of that State

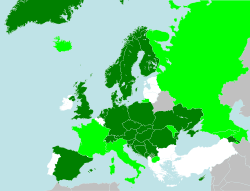

In most European countries the minority languages are defined by legislation or constitutional documents and afforded some form of official support. In 1992, Council of Europe adopted European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages to protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe.[3]

The signatories that have not yet ratified it as of 2012 are Azerbaijan, France, Ireland (since Irish is the first official language and there are no other minority languages), Iceland, Italy, Macedonia, Malta, Moldova, and Russia.

Canada

In Canada the term appears in the Constitution of Canada in the heading above section 23 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantees official language minority communities educational rights. In Canada, the term "minority language" is generally understood to mean whichever of the official languages is less spoken in a particular province or territory (i.e., English in Québec, French elsewhere).

Politics

Minority languages may be marginalised within nations for a number of reasons. These include having a relatively small number of speakers, a decline in the number of speakers, and popular belief of them as uncultured, primitive, or simple dialects when compared to the dominant language. Support for minority languages is sometimes viewed as supporting separatism, for example the ongoing revival of the Celtic languages (Irish, Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Manx, Cornish and Breton). Immigrant minority languages are often also seen as a threat and as indicative of the non-integration of these communities. Both of these perceived threats are based on the notion of the exclusion of the majority language speakers. Often this is added to by political systems by not providing support (such as education and policing) in these languages.

Speakers of majority languages can and do learn minority languages, through the large number of courses available.[4] It is not known whether most students of minority languages are members of the minority community re-connecting with the community's language, or others seeking to become familiar with it.

Controversy

There is a difference of views as to whether the protection of official languages by a state representing the majority speakers violates or not the human rights of minority speakers. In March 2013, Rita Izsák, UN Independent Expert on minority issues, said that "protection of linguistic minority rights is a human rights obligation and an essential component of good governance, efforts to prevent tensions and conflict, and the construction of equal and politically and socially stable societies".[5]

In Slovakia for example, the Hungarian community generally considers the 'language law' enacted in 1995 discriminative and inconsistent with the European Charter for the Protection of Regional or Minority languages, while majority Slovakians view that minority speakers' rights are guaranteed in accordance with the highest European standards and not discriminated against by the preferential status of the state language. The language law declares that "the Slovakian language enjoys a preferential status over other languages spoken on the territory of the Slovakian Republic" and as a result of a 2009 amendment, a fine of up to €5,000 may be imposed for a misdemeanor from the regulations protecting the preferential status of the state language, e.g. if the name of a shop or a business is indicated on a sign-board first in the minority language and only after it in Slovakian, or if in a bilingual text the minority language part is written with bigger fonts than its Slovakian equivalent, or if the bilingual text on a monument is translated from the minority language to the dominant language and not vice versa, or if a civil servant or doctor communicates with a minority speaker citizen in a minority language in a local community where the proportion of the minority speakers is less than 20%.

Sign languages are often not recognized as true natural languages even though they are supported by extensive research.

Speakers of auxiliary languages have also struggled for their recognition, perhaps partly because they are used primarily as second languages and have few native speakers.

Lacking recognition in some countries

Languages that have the status of a national language and are spoken by the majority population in at least one country, but lack recognition in countries where there is a significant minority linguistic community:

- Albanian - recognized minority language in many countries including Romania, but not recognized as a minority language in Greece - where 4% are ethnic Albanians.

- Bulgarian - recognized minority language in the Czech Republic (4,300 speakers), not officially recognized as minority language in Greece.

- German: official in Germany, Austria, Luxembourg, Belgium and Switzerland, minorities elsewhere in Europe, with recognition in South Tyrol, but no recognition in France.

- Hungarian: official in Hungary, co-official in Serbia's Vojvodina province (293,000 speakers), recognized minority language in the Czech Republic (14,000 speakers), lacking official status in Romania (1,447,544 speakers, 6.7% of the population), Slovakia (520,000 speakers, approximately 10% of the population) and Ukraine (170,000 speakers),

- Macedonian - Macedonian is not recognized as minority language in Greece and Bulgaria.

- Polish - recognized minority language in the Czech Republic (51,000 speakers), not officially recognized as minority language in Lithuania.

- Romanian: official in Romania, co-official in Vojvodina (30,000 speakers), recognized minority language in the Czech Republic (1,200 speakers), lacking official status in Serbia (2011 census - 35,330 [6] estimated 250,000[7]) northwestern Bulgaria (estimated 10,566 speakers) and in Ukraine (estimated 450,000 speakers).

- Russian: official in Russia, co-official in Belarus and Kazakhstan, lacking official status in Ukraine, Estonia, and Latvia (more than 25% of the population in the latter two).

- Serbian: official in Serbia, co-official in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, and minority status in Montenegro, Croatia, Macedonia, Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, and Romania. The minority status in Montenegro is controversial since the majority of the population (63.49%) declared Serbian as their mother tongue, and Serbian having been official until 2007.

Languages having no majority worldwide

Linguistic communities that form no majority in any country, but whose language has the status of an official language in at least one country:

- Tamil: 78 million speakers, official status in India, Sri Lanka, and Singapore

- Berber: 45 million speakers, official status in Morocco, Algeria, and Libya

- Kurdish: 22 million speakers, official status in Iraq

- Afrikaans: 13 million first or second language speakers (16 million speakers with basic knowledge), official status in South Africa, recognized regional language in Namibia

- Catalan: 9 million speakers, official status in Andorra, regional official status in Catalonia, the Valencian Community under the name of Valencian, and the Balearic Islands, Spain. Recognized regional language in Italy, and specifically on the island of Sardinia in Alghero. It has no official status in Northern Catalonia, France.

- Dutch Low Saxon: 4.8 million speakers, a minority language in the Netherlands, but also in Germany.

- Galician: 3-4 million speakers, regional official status in Galicia, Spain.

- Limburgish: 2 million speakers, a minority language in Netherlands, Belgium and Germany.

- Welsh: 622,000 speakers, regional official status in Wales, UK; minority in Chubut, Argentina with no legal recognition.

- Basque: 665,800 speakers, regional official status in the Basque Country (autonomous community) and Navarre in Spain.—although It has no official status in the Northern Basque Country in France.

- Frisian languages: 400,000 speakers, regional official in Netherlands, Denmark and Germany.

- Irish: 291,470 native speakers (1.66 million with some knowledge), official status in Ireland and an officially recognised minority language in the United Kingdom.

- Māori: 157,110 speakers, official status in New Zealand

- Romansh: 60,000 speakers, official status in Switzerland (Graubünden).

- Cherokee: 22,500 speakers, official status within the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

- Scottish Gaelic: 87,000 people with some ability, 57,375 of which are first and second language speakers. Regional status in Scotland, UK. 300 native speakers, 2,320 overall in Canada, minority status. About 1,900 speaker minority in America.

Lawsuits

- Alexander v. Sandoval

- Arsenault-Cameron v. Prince Edward Island

- Casimir v. Quebec (Attorney General)

- Charlebois v. Saint John (City)

- Devine v. Quebec (Attorney General)

- Doucet-Boudreau v. Nova Scotia (Minister of Education)

- Gosselin (Tutor of) v. Quebec (Attorney General)

- Katzenbach v. Morgan

- Mahe v. Alberta

- R. v. Beaulac

- Société des Acadiens v. Association of Parents

Treasure Language

A treasure language is one of the thousands of small languages still spoken in the world today. The term was proposed by the Rama people of Nicaragua as an alternative to heritage language, indigenous language, and "ethnic language", names that are considered pejorative in the local context.[8] The term is now also used in the context of public storytelling events.[9]

The term "treasure language" references the desire of speakers to sustain the use of their mother tongue into the future:

[The] notion of treasure fit the idea of something that had been buried and almost lost, but was being rediscovered and now shown and shared. And the word treasure also evoked the notion of something belonging exclusively to the Rama people, who now attributed it real value and had become eager and proud of being able to show it to others.[8]

Accordingly, the term is distinct from endangered language for which objective criteria are available, or heritage language which describes an end-state for a language where individuals are more fluent in a dominant language.[10]

See also

- European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

- List of languages without official status

- Indigenous language

- Indigenous Tweets

- Language education

- Language revival

- Linguistic demography

- Linguistic rights

- List of endangered languages

- List of language self-study programs

- Minority group

- Minoritized languages

- Regional language

- Global language system

- Convention against Discrimination in Education (Article 5)

- Language minority students in Japanese classrooms

- National unity

External links

References

- ↑ ONU members

- ↑ "Ethnologue statistics". Summary by world area | Ethnologue. SIL.

- ↑ Hult, F.M. (2004). Planning for multilingualism and minority language rights in Sweden. Language Policy, 3(2), 181-201.

- ↑ "List of Languages with Courses Available". Lang1234. Retrieved 12 Sep 2012.

- ↑ "Protection of minority languages is a human rights obligation, UN expert says". UN News Centre. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ http://media.popis2011.stat.rs/2011/prvi_rezultati.pdf Serbian Preliminary 2011 Census Results

- ↑ "Romanian". Ethnologue. 1999-02-19. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- 1 2 Grinevald, Colette; Pivot, Bénédicte (2013). "On the revitalization of a 'treasure language': The Rama Language Project of Nicaragua". In Jones, Mari; Ogilvie, Sarah. Keeping Languages Alive: Documentation, Pedagogy and Revitalization. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139245890.018.

- ↑ "Languages Treasured but Not Lost". East Bay Express. Oakland. 2016-02-17. Retrieved 2017-05-09.

- ↑ Hale, Kenneth; Hinton, Leanne, eds. (2001). The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice. Emerald Group Publishing.