Glutamine

L-Glutamine | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Glutamine | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| Abbreviations | Gln, Q |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.266 |

| EC Number | 200-292-1 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties[2] | |

| C5H10N2O3 | |

| Molar mass | 146.15 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | decomposes around 185°C |

| soluble | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.2 (carboxyl), 9.1 (amino) |

Chiral rotation ([α]D) |

+6.5º (H2O, c = 2) |

| Pharmacology | |

| A16AA03 (WHO) | |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Glutamine (symbol Gln or Q)[3] is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Its side chain is similar to that of glutamic acid, except the carboxylic acid group is replaced by an amide. It is classified as a charge-neutral, polar amino acid. It is non-essential and conditionally essential in humans, meaning the body can usually synthesize sufficient amounts of it, but in some instances of stress, the body's demand for glutamine increases, and glutamine must be obtained from the diet.[4][5] It is encoded by the codons CAA and CAG.

In human blood, glutamine is the most abundant free amino acid.[6]

The dietary sources of glutamine includes especially the protein-rich foods like beef, chicken, fish, dairy products, eggs, vegetables like beans, beets, cabbage, spinach, carrots, parsley, vegetable juices and also in wheat, papaya, brussel sprouts, celery, kale and fermented foods like miso.

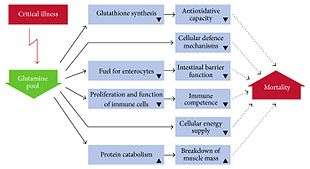

Functions

Glutamine plays a role in a variety of biochemical functions:

- Protein synthesis, as any other of the 20 proteinogenic amino acids

- Lipid synthesis, especially by cancer cells.[7][8]

- Regulation of acid-base balance in the kidney by producing ammonium[9]

- Cellular energy, as a source, next to glucose[10]

- Nitrogen donation for many anabolic processes, including the synthesis of purines[6]

- Carbon donation, as a source, refilling the citric acid cycle[11]

- Nontoxic transporter of ammonia in the blood circulation

- Precursor to the neurotransmitter glutamate

On the level of tissue, glutamine plays a role in maintaining the normal integrity of the intestinal mucosa.,[12] but randomised trials provide no evidence of any benefit of nutritional supplementation.[12]

Producers

Glutamine is synthesized by the enzyme glutamine synthetase from glutamate and ammonia. The most relevant glutamine-producing tissue is the muscle mass, accounting for about 90% of all glutamine synthesized. Glutamine is also released, in small amounts, by the lungs and brain.[13] Although the liver is capable of relevant glutamine synthesis, its role in glutamine metabolism is more regulatory than producing, since the liver takes up large amounts of glutamine derived from the gut.[6]

Consumers

The most eager consumers of glutamine are the cells of intestines,[6] the kidney cells for the acid-base balance, activated immune cells,[14] and many cancer cells.[7][8][11][15]

Uses

Nutrition

Glutamine is the most abundant naturally occurring, nonessential amino acid in the human body, and one of the few amino acids that can directly cross the blood–brain barrier.[6] Humans obtain glutamine through catabolism of proteins in foods they eat.[16] In states where tissue is being built or repaired, like growth of babies, or healing from wounds or severe illness, glutamine becomes conditionally essential.[16]

Sickle cell disease

In 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved L-glutamine oral powder, marketed as Endari, to reduce severe complications of sickle cell disease in people aged 5 years and older with the disorder.[1]

Medical food

Glutamine is marketed as medical food and is prescribed when a medical professional believes a person in their care needs supplementary glutamine due to metabolic demands beyond what can be met by endogenous synthesis or diet.[17]

Safety

Glutamine is safe in adults and in preterm infants.[18] Although glutamine is metabolized to glutamate and ammonia, both of which have neurological effects, their concentrations are not increased much, and no adverse neurological effects were detected.[18] The observed safe level for supplemental L-glutamine in normal healthy adults is 14 g/day.[19]

Adverse effects of glutamine have been described for people receiving home parenteral nutrition and those with liver-function abnormalities.[20] Although glutamine has no effect on the proliferation of tumor cells, it is still possible that glutamine supplementation may be detrimental in some cancer types.[21]

Ceasing glutamine supplementation in people adapted to very high consumption may initiate a withdrawal effect, raising the risk of health problems such as infections or impaired integrity of the intestine.[21]

Structure

Glutamine can exist in either of two enantiomeric forms, L-glutamine and D-glutamine. The L-form is found in nature. Glutamine contains an α-amino group which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions and a carboxylic acid group which is in the deprotonated −COO− form, known as carboxylate, under physiological conditions.

Research

Glutamine mouthwash may be useful to prevent oral mucositis in people undergoing chemotherapy but intravenous glutamine does not appear useful to prevent mucositis in the GI tract.[23]

Glutamine supplementation was thought to have potential to reduce complications in people who are critically ill or who have had abdominal surgery but this was based on poor quality clinical trials.[24] Supplementation does not appear to be useful in adults or children with Crohn's disease or inflammatory bowel disease, but clinical studies as of 2016 were underpowered.[12] Supplementation does not appear to have an effect in infants with significant problems of the stomach or intestines.[25]

See also

References

- 1 2 Commissioner, Office of the (7 July 2017). "Press Announcements - FDA approves new treatment for sickle cell disease". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Weast, Robert C., ed. (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. C-311. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8. .

- ↑ "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. 1983. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ↑ Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements, published by the Institute of Medicine's Food and Nutrition Board, currently available online at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-05. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- ↑ Lacey, JM; Wilmore, DW (August 1990). "Is glutamine a conditionally essential amino acid?". Nutrition Reviews. 48 (8): 297–309. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1990.tb02967.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brosnan, John T. (June 2003). "Interorgan amino acid transport and its regulation". J. Nutr. 133 (6 Suppl 1): 2068S–2072S. PMID 12771367.

- 1 2 Corbet C, Feron O (2015). "Metabolic and mind shifts: from glucose to glutamine and acetate addictions in cancer". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 18 (4): 346–353. doi:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000178. PMID 26001655.

- 1 2 Gouw AM, Toal GG, Felsher DW (2016). "Metabolic vulnerabilities of MYC-induced cancer". Oncotarget. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.7223. PMID 26863454.

- ↑ Hall, John E.; Guyton, Arthur C. (2006). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 393. ISBN 0-7216-0240-1.

- ↑ Aledo, J. C. (2004). "Glutamine breakdown in rapidly dividing cells: Waste or investment?". BioEssays. 26 (7): 778–785. doi:10.1002/bies.20063. PMID 15221859.

- 1 2 Yuneva, M.; Zamboni, N.; Oefner, P.; Sachidanandam, R.; Lazebnik, Y. (2007). "Deficiency in glutamine but not glucose induces MYC-dependent apoptosis in human cells". The Journal of Cell Biology. 178 (1): 93–105. doi:10.1083/jcb.200703099. PMC 2064426. PMID 17606868.

- 1 2 3 Yamamoto, T; Shimoyama, T; Kuriyama, M (8 December 2016). "Dietary and enteral interventions for Crohn's disease". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 44: 69–73. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2016.11.011. PMID 27940405.

- ↑ Newsholme, P.; Lima, M. M. R.; Procopio, J.; Pithon-Curi, T. C.; Doi, S. Q.; Bazotte, R. B.; Curi, R. (2003). "Glutamine and glutamate as vital metabolites". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 36 (2): 153–163. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2003000200002. PMID 12563517.

- ↑ Newsholme, P. (2001). "Why is L-glutamine metabolism important to cells of the immune system in health, postinjury, surgery or infection?". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (9 Suppl): 2515S–2522S, discussion 2522S–4S. PMID 11533304.

- ↑ Fernandez-de-Cossio-Diaz, Jorge; Vazquez, Alexei (2017-10-18). "Limits of aerobic metabolism in cancer cells". Scientific Reports. 7 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-017-14071-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5647437. PMID 29044214.

- 1 2 Watford, Malcolm (September 2015). "Glutamine and glutamate: Nonessential or essential amino acids?". Animal Nutrition. 1 (3): 119–122. doi:10.1016/j.aninu.2015.08.008.

- ↑ "GlutaSolve, NutreStore, SYMPT-X G.I., SYMPT-X Glutamine (glutamine) Drug Side Effects, Interactions, and Medication Information on eMedicineHealth". eMedicineHealth. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- 1 2 Garlick PJ (2001). "Assessment of the safety of glutamine and other amino acids". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (9 Suppl): 2556S–61S. PMID 11533313. Retrieved 2017-05-21.

- ↑ Shao A, Hathcock JN (2008). "Risk assessment for the amino acids taurine, L-glutamine and L-arginine". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 50 (3): 376–99. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2008.01.004. PMID 18325648. Retrieved 2017-05-21.

- ↑ Buchman AL (2001). "Glutamine: commercially essential or conditionally essential? A critical appraisal of the human data". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 74 (1): 25–32. PMID 11451714. Retrieved 2017-05-21.

- 1 2 Holecek M (2013). "Side effects of long-term glutamine supplementation". JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 37 (5): 607–16. doi:10.1177/0148607112460682. PMID 22990615. Retrieved 2017-05-21.

- ↑ Stehle P, Kuhn KS (2015). "Glutamine: an obligatory parenteral nutrition substrate in critical care therapy". Biomed Res Int. 2015: 545467. doi:10.1155/2015/545467. PMC 4606408. PMID 26495301.

- ↑ Berretta, M; Michieli, M; Di Francia, R; Cappellani, A; Rupolo, M; Galvano, F; Fisichella, R; Berretta, S; Tirelli, U (1 January 2013). "Nutrition in oncologic patients during antiblastic treatment". Frontiers in Bioscience. 18: 120–32. doi:10.2741/4091. PMID 23276913.

- ↑ Tao, KM; Li, XQ; Yang, LQ; Yu, WF; Lu, ZJ; Sun, YM; Wu, FX (9 September 2014). "Glutamine supplementation for critically ill adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD010050. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010050.pub2. PMID 25199493.

- ↑ Moe-Byrne, T; Brown, JV; McGuire, W (18 April 2016). "Glutamine supplementation to prevent morbidity and mortality in preterm infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD001457. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001457.pub6. PMID 27089158.

External links

- Glutamine spectra acquired through mass spectroscopy