Medical Renaissance

The Medical Renaissance, from 1400 to 1700 AD, is the period of progress in European medical knowledge, and a renewed interest in the ideas of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Such medical discoveries during the Medical Renaissance are credited with paving the way for modern medicine.

Background

The Medical Renaissance began just as the original Renaissance did, in the early 1400s. Medical researchers continued their Renaissance-evoked practices into the late 1600s. Florence, Italy was credited by most historians for being an influential hub for medical research and communications of proven advancements in the field of medicine.[1][2] Progress made during the Medical Renaissance depended on several factors.[3][4] Printed books based on movable type, adopted in Europe from the middle of the 15th century, allowed the diffusion of medical ideas and anatomical diagrams. Linacre, Erasmus, Leonicello and Sylvius are among the list of the first scholars most credited for the starting of the Medical Renaissance.[2] Following after is Andreas Vesalius's publication of De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human body) in 1543. Better knowledge of the original writings of Galen in particular, developed into the learned medicine tradition through the more open attitudes of Renaissance humanism. Church control of the teachings of the medical profession and universities diminished, and dissection was more often possible.

Medical Procedures on the Deceased

The development of autopsy allowed society to use it for forensic and health purposes. In the early 1300s, Italian cities established a group of doctors to assist in investigating the cause of death in murder trials. In 1302, the death of Azzolino degli Onesti was investigated because it was suspected that he was poisoned. From the surgeon’s examination, they concluded that the cause of death was from a large amount of blood that gathered around the chilic vein and the veins of the liver.[5]

Doctors began doing autopsies on their private patients during the fifteenth century. In 1486, the Florentine patrician, Bartolomea Rinieri, was autopsied at her request so that her daughter could be treated for what caused her death. The surgeons discovered a diseased womb that had hardened. High-class members of society could request their own postmortem because they had the financial means.[5]

Craniotomies were also used by surgeons to find the cause of death. This practice dates back to the thirteenth century. The Medicis, a powerful family in Florence during the Renaissance, had skulls that revealed craniotomies and autopsies had been performed. The procedure was also done on illegitimate members of the family and children. Every skeleton of the Medici family shows signs of embalming, a practice only done for the elite.[6]

The surgeons of the era were also categorized as a class system. They were acknowledged as master surgeons, “surgeons of the long robe,” or the lower class of barber surgeons, “surgeons of the short robe”.[7]

Individuals

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

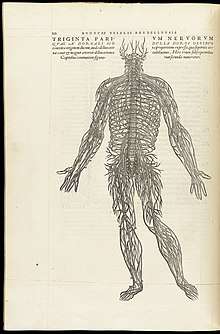

Leonardo da Vinci made many contributions in the fields of science and technology. His research centered around his desire to learn more about how the human brain processes visual and sensory information and how that connects to the soul. Though his artwork was widely observed before, some of his original research was not made public until the 20th century. Some of da Vinci's research involved studying vision. He believed that visual information entered the body through the eye, then continue by sending nerve impulses through the optic nerve, and eventually reaching the soul. Da Vinci subscribed to the ancient notion that the soul was housed in the brain. He did research on the role of the spinal cord in humans by studying frogs. He noted that as soon as the frogs medulla of the spine is broken, the frog would die. This led him to believe that the spine is the basis for the sense of touch, cause of movement, and the origin of nerves. As a result of his studies on the spinal cord, he also came to the conclusion that all peripheral nerves begin from the spinal cord. Da Vinci also did some research on the sense of smell. He is credited with being the first to define the olfactory nerve as one of the cranial nerves.[8]Leonardo da Vinci made his anatomical sketches based on observing and dissecting 30 cadavers. His sketches were very detailed and included organs, muscles of superior extremity, the hand, and the skull. Leonardo was well known for his three-dimensional drawings. His anatomical drawings were not found until 380 years after his death.[9]

Ambroise Paré (1510–1590)

Paré was a French surgeon, anatomist and an inventor of surgical instruments. He was a military surgeon during the French campaigns in Italy of 1533–36. It was here that, having run out of boiling oil (which was the accepted way of treating firearm wounds), Paré turned to an ancient Roman remedy: turpentine, egg yolk and oil of roses. He applied it to the wounds and found that it relieved pain and sealed the wound effectively. Paré also introduced the ligatures of arteries; silk threads would be used to tie up the arteries of amputated limbs to try to stop the bleeding. As antiseptics had not yet been invented this method led to an increased fatality rate and was abandoned by medical professionals of the time.[10] Additionally, Paré set up a school for midwives in Paris and designed artificial limbs.[11]

Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564)

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Andreas Vesalius |

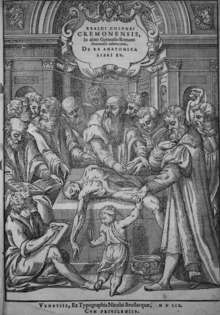

Vesalius was a Flemish-born anatomist whose dissections of the human body helped to rectify the misconceptions made in Ancient Times, particularly by Galen, who (for religious reasons) had been able only to study animals such as dogs and monkeys.[12] He wrote many books on anatomy from his observations; his best-known work was De Humani Corporis Fabrica, published in 1543, which contained detailed drawings of the human body posed as if alive.[13] This book contained many different anatomic sketches that he made upon examining and dissecting cadavers. These sketches were a combination of Italian and Gothic art. Vesalius identified the anatomical errors in Galen's findings and challenged the academic world.[9] He changed how human anatomy was viewed and researched and is considered a legacy in the medical world.[14] Nicolaus Copernicus published his book on planetary motion in 1543, one month before Vesalius published his work on anatomy. The work by Copernicus overturned the medieval belief that the earth lay at the center of the universe, and the work by Vesalius overturned the old authorities about the structure of the human body. In 1543, these two separate books fostered a change in understanding of the place of mankind within the macrocosmic structure of the universe and the microcosmic structure of the human body.[15]

William Harvey (1578–1657)

William Harvey was an English medical doctor-physicist, known for his contributions in heart and blood movement. William Harvey fully believed all medical knowledge should be universal, and he made this his works goal. Accomplished historians credit him for his boldness in his experimental work and his everlasting eagerness to implement modern practice.[16] Although not the first to propose pulmonary circulation (Ibn al-Nafis, Michael Servetus and Realdo Colombo preceded him), he is credited as the first person in the Western world to give quantitative arguments for the circulation of blood around the body.[17] William Harvey's extensive work on the body's circulation can be found in the written work titles, "The Motu Cordis".This work opens up with clear definitions of anatomy as well as types of anatomy which clearly outlined a universal meaning of these words for various Renaissance physicians. Anatomy, as defined by William Harvey is, "the faculty that by ocular inspection and dissection [grasps] the uses and actions of the parts."[16] In other words, to be able to identify the actions or roles each part of the body plays in the overall function of the body by dissection, followed by visual identification. These were the foundation for the further research on the heart and blood vessels.[18]

Hieronymus Fabricius (1537-1619)

Hieronymus Fabricius is an anatomist and surgeon that prepared a human and animal anatomy atlas and these illustrations were used in his work, Tabulae Pictae. This work includes illustrations from many different artists and Fabricius is credited for providing a turning point in anatomical illustration. Fabricius' illustrations were of natural size and natural colors. After Fabricius' death, Tabulae Pictae disappeared and wasn't again discovered until 1909.[9] Fabricus focused on the human brain and the fissures that are inside of the brain. In Tabulae Pictae, he described the cerebral fissure that separates the temporal lobe from the frontal lobe.[19] He also studied veins and was the first to discover the valves inside of veins.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ "Medical Renaissance in Florence". European Journal of General Practice. 12 (2): 51–51. 2006-01-01. doi:10.1080/13814780600940767. ISSN 1381-4788.

- 1 2 Toledo-Pereyra, Luis H. (2015-05-04). "Medical Renaissance". Journal of Investigative Surgery. 3: 127–130. doi:10.3109/08941939.2015.1054747. ISSN 0894-1939.

- ↑ OCR GCSE: Medicine Through Time

- ↑ Parragon, World History Encyclopedia

- 1 2 Park, Katherine (1994). "The criminal and the saintly body: Autopsy and dissection in Renaissance Italy". Renaissance Quarterly.

- ↑ Lanska, Douglas. The fine arts, neurology, and neuroscience : history and modern perspectives : neuro-historical dimensions. ELSEVIER SCIENCE BV. ISBN 978-0-444-62730-8.

- ↑ Giuffra, Valentina (2016). "Autoptic practices in 16th-18th century Florence: Skeletal evidences from the Medici family". International journal of paleopathology. 15: 21. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2016.09.004.

- ↑ Pevsner, Jonathan (2002). "Leonardo da Vinci's contributions to neuroscience". Trends in Neurosciences. 25 (4): 217–220. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02121-4.

- 1 2 3 Ghosh, Sanjib Kumar (2015-03-01). "Evolution of illustrations in anatomy: A study from the classical period in Europe to modern times". Anatomical Sciences Education. 8 (2): 175–188. doi:10.1002/ase.1479. ISSN 1935-9780.

- ↑ Grendler, Paul F. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Renaissanc. New York: Scribner's. p. 399. ISBN 0-684-80511-1.

- ↑ Ambroise Pare

- ↑ Andreas Vesalius

- ↑ BBC - History - Andreas Vesalius ( 1514–1564)

- ↑ Mesquita, Evandro Tinoco; Júnior, Celso Vale de Souza; Ferreira, Thiago Reigado. "Andreas Vesalius 500 years - A Renaissance that revolutionized cardiovascular knowledge". Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Cardiovascular. doi:10.5935/1678-9741.20150024. PMC 4462973. PMID 26107459.

- ↑ Brotton, Jerry (2006). The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192801630.

- 1 2 Distelzweig, Peter (2014-01-01). ""Meam de motu & usu cordis, & circuitu sanguinis sententiam": teleology in William Harvey's De motu cordis". Gesnerus. 71 (2): 258–270. ISSN 0016-9161. PMID 25707098.

- ↑ Spotlight Science 9 (GCSE Science Text Book)

- ↑ Kids Work! > History of Medicine

- 1 2 Collice, Massimo; Collice, Rosa; Riva, Alessandro (2008-10-01). "Who Discovered the Sylvian Fissure?". Neurosurgery. 63 (4): 623–628. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000327693.86093.3f. ISSN 0148-396X.

Further reading

- Andrew Wear; Roger Kenneth French; Iain M. Lonie (1985). The Medical Renaissance of the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30112-2.

- Siraisi, Nancy G. (1 January 1986). "Medieval and Renaissance Medicine: Continuity and Diversity". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 41 (4): 391–394. doi:10.1093/jhmas/41.4.391.