History of Bengal

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Bengal |

|

|

Ancient Geopolitical units |

|

Medieval and Early Modern periods |

|

European colonisation

|

|

Calendar |

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

|

Bengali homeland |

|

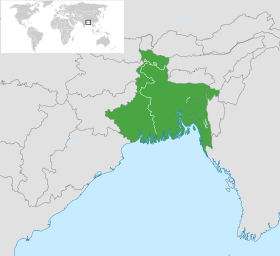

The history of Bengal is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions of South Asia and Southeast Asia. It includes modern-day Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal and Assam's Barak Valley, located in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, at the apex of the Bay of Bengal and dominated by the fertile Ganges delta. The advancement of civilization in Bengal dates back four millennia.[1] The region was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans as Gangaridai. The Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers act as a geographic marker of the region, but also connects the region to the broader Indian subcontinent.[2] Bengal, at times, has played an important role in the history of the Indian subcontinent.

The area's early history featured a succession of Indian empires, internal squabbling, and a tussle between Hinduism and Buddhism for dominance. Ancient Bengal was the site of several major Janapadas (kingdoms), while the earliest cities date back to the Vedic period. A thalassocracy and an entrepôt of the historic Silk Road,[2] Ancient Bengal established colonies on Indian Ocean islands and in Southeast Asia;[3] had strong trade links with Persia, Arabia and the Mediterranean that focused on its lucrative cotton muslin textiles.[4] The region was part of several ancient pan-Indian empires, including the Mauryans and Guptas. It was also a bastion of regional kingdoms. The citadel of Gauda served as capital of the Gauda Kingdom, the Buddhist Pala Empire (eighth to 11th century) and Hindu Sena Empire (11th–12th century). This era saw the development of Bengali language, script, literature, music, art and architecture.

From the 13th century onward, the region was controlled by the Bengal Sultanate, Hindu Rajas (kings),[5] and Baro-Bhuyan landlords. During the Medieval and Early Modern periods, Bengal was home to several medieval Hindu principalities, including the Koch Kingdom, Kingdom of Mallabhum, Kingdom of Bhurshut and Kingdom of Tripura; the realm of powerful Hindu Rajas notably Pratapaditya and Raja Sitaram Ray. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Isa Khan, a Muslim Rajput chief, who led the Baro Bhuiyans (twelve landlords), dominated the Bengal delta.[6] Afterwards, the region came under the suzerainty of the Mughal Empire, as its wealthiest province. Under the Mughals, Bengal Subah generated 50% of the empire's GDP and 12% of the world's GDP,[7] globally dominant in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding,[8][9][10] with the capital Dhaka having a population exceeding a million people.[7] The gradual decline of the Mughal Empire led to quasi-independent states under the Nawabs of Bengal, subsequent Maratha expeditions in Bengal, and finally the conquest by the British East India Company.

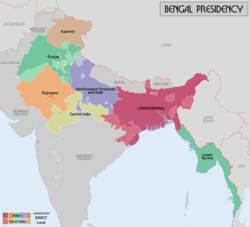

The British took control of the region from the late 18th century. The company consolidated their hold on the region following the Battle of Plassey in 1757 and Battle of Buxar in 1764 and by 1793 took complete control of the region. The plunder of Bengal directly contributed to the Industrial Revolution in Britain,[8][9][10][11] with the capital amassed from Bengal used to invest in British industries such as textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution and greatly increase British wealth, while at the same time leading to deindustrialization and famines in Bengal.[8][9][10] Kolkata (or Calcutta) served for many years as the capital of British controlled territories in India. The early and prolonged exposure to British administration resulted in the expansion of Western education, culminating in development of science, institutional education, and social reforms in the region, including what became known as the Bengali renaissance. A hotbed of the Indian independence movement through the early 20th century, Bengal was divided during India's independence in 1947 along religious lines into two separate entities: West Bengal—a state of India—and East Bengal—a part of the newly created Dominion of Pakistan that later became the independent nation of Bangladesh in 1971.

Etymology

The exact origin of the word Bangla is unknown, though it is believed to be derived from the Dravidian-speaking tribe Bang/Banga that settled in the area around the year 1000 BCE.[12][13] Other accounts speculate that the name is derived from Venga (Bôngo), which came from the Austric word "Bonga" meaning the Sun-god. According to the Mahabharata, the Puranas and the Harivamsha, Vanga was one of the adopted sons of King Vali who founded the Vanga Kingdom. It was either under Magadh or under Kalinga Rules except few years under Pals.The Muslim accounts refer that "Bong", a son of Hind (son of Hām who was a son of Prophet Noah/Nooh) colonised the area for the first time.[14] The earliest reference to "Vangala" (Bôngal) has been traced in the Nesari plates (805 CE) of Rashtrakuta Govinda III which speak of Dharmapala as the king of Vangala. The records of Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty, who invaded Bengal in the 11th century, speak of Govindachandra as the ruler of Vangaladesa.[15][16][17] Shams-ud-din Ilyas Shah took the title "Shah-e-Bangla" and united the whole region under one government.

An interesting theory of the origin of the name is provided by Abu'l-Fazl in his Ain-i-Akbari. According to him, "[T]he original name of Bengal was Bung, and the suffix "al" came to be added to it from the fact that the ancient rajahs of this land raised mounds of earth 10 feet high and 20 in breadth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al". From this suffix added to the Bung, the name Bengal arose and gained currency".[18]

Ancient Bengal

Pre-historic Bengal

Stone Age tools dating back 20,000 years have been excavated in the state.[19] Remnants of Copper Age settlements in the Bengal region date back 4,000 years.[20] The original settlers spoke non-Aryan languages — they may have spoken Austric or Austro-Asiatic languages like the languages of the present-day Kola, Bhil, Santhal, Shabara, and Pulinda people. At a subsequent age, peoples speaking languages from two other language families — Dravidian and Tibeto-Burman —seem to have settled in Bengal. Archaeological discoveries during the 1960s furnished evidence of a degree of civilisation in certain parts of Bengal as far back as the first millennium BCE.

Bengal's early literature

Some references indicate that the primitive people in Bengal were different in ethnicity and culture from the Vedic people beyond the boundary of Aryavarta and who were classed as "Dasyus". The Bhagavata Purana classes them as sinful people while Dharmasutra of Baudhayana prescribes expiatory rites after a journey among the Pundras and Vangas. Mahabharata speaks of Paundraka Vasudeva who was lord of the Pundras and who allied himself with Jarasandha against Krishna. The Mahabharata also speaks of Bengali kings called Chitrasena and Sanudrasena who were defeated by Bhima and Kalidasa mentions Raghu defeating a coalition of Vanga kings.

Proto-History

Hindu scriptures such as the Mahabharata suggest that ancient Bengal was divided among various tribes or kingdoms, including the Nishadas and kingdoms known as the Janapadas: Vanga (southern Bengal), Pundra (northern Bengal), and Suhma (western Bengal) according to their respective totems. These Hindu sources, written by Indo-Aryans speakers in what is now Punjab and Uttar Pradesh, suggest that the peoples of Bengal were not Indo-Aryan speakers. However, Jain scriptures identify Vanga and Anga in Bengal as Indo-Aryan speakers. While western Bengal, as part of Magadha, became part of the Indo-Aryan speaking polity by the 7th century BCE, the Nanda Dynasty was the first historical state to unify most of Bengal under Indo-Aryan rule.

Overseas Colonization

The Vanga Kingdom was the first powerful seafaring nation of South Asia, especially Bengal. They had overseas trade relations with Java, Sumatra and Siam (modern-day Thailand). According to Mahavamsa, the Vanga prince Vijaya Simha conquered Lanka (modern-day Sri Lanka) in 544 BCE and gave the name "Sinhala" to the country. Bengali people migrated to the Malay Archipelago and Siam (in modern Thailand), establishing their own colonies there.[21]

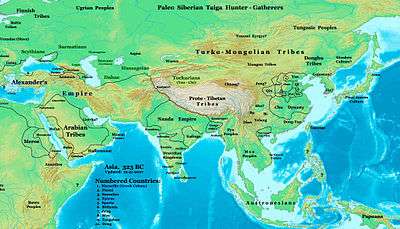

Gangaridai

Though north and west Bengal were part of the Magadhan empire southern Bengal thrived and became powerful with her overseas trades. In 326 BCE, with the invasion of Alexander the Great the region again came to prominence. The Greek and Latin historians suggested that Alexander the Great withdrew from India anticipating the valiant counterattack of the mighty Gangaridai empire that was located in the Bengal region. Alexander, after the meeting with his officer, Coenus, was convinced that it was better to return. Diodorus Siculus mentions Gangaridai to be the most powerful empire in India whose king possessed an army of 20,000 horses, 200,000 infantry, 2,000 chariots and 4,000 elephants trained and equipped for war.

Classical Bengal

The pre-Gupta period of Bengal is shrouded with obscurity. Before the conquest of Samudragupta Bengal was divided into two kingdoms: Pushkarana and Samatata. An inscription of Pushkaranadhipa (the ruler of Pushkarana) Chandravarman has been found in a cave in the Shushunia hills. Chandragupta II had defeated a confederacy of Vanga kings resulting in Bengal becoming part of the Gupta Empire.

During Gupta rule, the Bengal economy was part of a global trade network. The main social groups dominating in the socio-economic life were the Nagarshreshthi (city representative of seth class, i.e. bankers), 'Sarthabaha' (merchant class), and 'kulik' (artisan class).[22]

Gauda Kingdom

By the 6th century, the Gupta Empire, which ruled over the northern Indian subcontinent had largely broken up. Eastern Bengal splintered into the kingdoms of Vanga, Samatata and Harikela while the Gauda kings rose in the west with their capital at Karnasuvarna (near modern Murshidabad). Shashanka, a vassal of the last Gupta Emperor proclaimed independence and unified the smaller principalities of Bengal (Gaur, Vanga, Samatata). He vied for regional power with Harshavardhana in northern India after treacherously murdering Harsha's elder brother Rajyavardhana. Harsha's continuous pressure led to the gradual weakening of the Gauda kingdom founded by Shashanka and finally ended with his death. This burst of Bengali power ended with the overthrow of Manava (his son), Bengal descended into a period marked by disunity and intrigue once more.

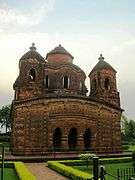

Mallabhum Kingdom

|

Mallabhum kingdom was ruled by the Malla kings of Bishnupur, primarily in present-day area of Indian state of West Bengal from the 7th century CE. The Rajas of Bishnupur were also known as Malla kings. Malla is a Sanskrit word meaning wrestler but there could be some links with the Mal tribes of the area, who had intimate connection with the Bagdis.[23] The Malla Rajas ruled over the territory in the south-western part of present West Bengal and a part of southeastern Jharkhand.[23]

From around 7th century CE till around the 19th century, for around a millennium, history of Bankura district is identical with the rise and fall of the Hindu Rajas of Bishnupur.[23] The legends of Bipodtarini Devi are associated with Malla Kings of Bishnupur.[24] The kingdom's lasting legacy is its famous terracotta temples.[25][26]

Late Classical Bengal

Pala Era

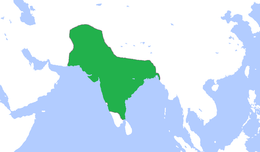

The Pala Empire (750–1120) was the first independent Buddhist dynasty of Bengal. The name Pala (Bengali: পাল) means protector and was used as an ending to the names of all Pala monarchs. The Palas were followers of the Mahayana and Vajrayana schools of Buddhism. Gopala I (750–770) was its first ruler. He came to power in 750 in the Gauḍa Gopala reigned from about 750–770 and consolidated his position by extending his control over all of Bengal.

The Pala dynasty lasted for four centuries and ushered in a period of stability and prosperity in Bengal. They created many temples and works of art as well as supported the important ancient higher-learning institutions of Nalanda and Vikramashila. The Somapura Mahavihara built by Emperor Dharmapala is the greatest Buddhist vihara in the Indian subcontinent.

The empire reached its peak under Emperor Dharmapala (770–810) and Devapala (810–850). Dharmapala extended the empire into the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent. According to Pala copperplate inscriptions, his successor Devapala exterminated the Utkalas, conquered the Pragjyotisha Kingdom of Assam, shattered the pride of the Huna people and humbled the lords of Gurjara-Pratihara and the Rashtrakuta dynasty.

The death of Devapala in 850 ended the period of ascendancy of the Pala dynasty and several independent dynasties and kingdoms emerged during this time. However, Mahipala rejuvenated the reign of the Palas. He recovered control over all of Bengal and expanded the empire. He survived the invasions of Rajendra Chola I and the Chalukya dynasty. After Mahipala I the Pala dynasty again saw its decline until Ramapala (1077–1130), the last great ruler of the dynasty, managed to retrieve the position of the dynasty to some extent. He crushed the Varendra Rebellion and tried to extend his empire farther to Kamarupa, Odisha and northern India. In his endeavor to conquer the Utkala and Koshala, parts of Odisha today, he had to contest with the mighty Ganga king Anangabhima Chodaganga Deva. Eventually Anangabhimadeva defeated Ramapala and united the regions of Trikalinga (Utkala, Koshala and Kalinga) into a major empire famous in history as the Eastern Ganga empire of Kalinga. While Anangabhimadeva defeated the Palas successively and counquered southern Bengal, he had to face stiffer opposition in the south from the great Chola ruler, Kulothunga Chola I. Since then the region of Bengal starting from the river Hooghly became the northern boundary of the Odishan emperors right from the Imperial Eastern Gangas to the mighty Gajapatis.

The Pala dynasty era was the golden era of Bengal. Never had the Bengali people reached such height of power and glory to that extent. The Palas were responsible for the introduction of Mahayana Buddhism in Tibet, Bhutan and Burma. It was during the Pala period Bengal became the main center of Buddhist as well as secular learning. Nalanda, Vikramashila and Somapura Mahavihara flourished and prospered under the patronage of the Pala rulers. Dharmapala and Devapala were two great patrons of Buddhism, secular education and culture.

The Palas also had extensive trade as well as influence in Southeast Asia. This can be seen in the sculptures and architectural style of the Sailendra (present-day Malay Peninsula, Java and Sumatra). However, the economy of Bengal became more dependent on agriculture. Importance of merchant and financial classes declined. While the monarchs were Buddhists, land grants to Brahmin agriculturalists was common.[22]

Chola and Chalukya invasions

Invasions by the Chola dynasty and Western Chalukya Empire led to the decline of the Pala dynasty in Bengal and to the establishment of the Sena dynasty.

Rajendra Chola I invaded Bengal between 1021 and 1023 CE.[27] According to the records of Rajendra Chola, the pretext for invading Bengal was to fetch water of the Ganges, but in the process he humbled the rulers of Bengal and returned home not only with Ganges water but with considerable booty.[27] The rulers of Bengal who were defeated by Rajendra Chola were Dharmapala, Ranasura and Govindachandra, who might have been feudatories of Mahipala.[27]

The Western Chalukya Empire invaded from South India during the reign of Someshvara I, led by his son, Vikramaditya VI, who defeated the kings of Gauḍa and Kamarupa.[28] This invasion of this ethnic Kannada ruler brought his countrymen from Karnataka into Bengal, which explains the southern origin of the Sena dynasty.[28]

Chandra Dynasty

The Chandra dynasty were a family who ruled over the kingdom of Harikela in eastern Bengal (comprising the ancient lands of Harikela, Vanga and Samatala) for roughly a century and a half from the beginning of the 10th century CE. Their empire also encompassed Vanga and Samatala, with Srichandra expanding his domain to include parts of Kamarupa. Their empire was ruled from their capital, Vikrampur (modern Munshiganj) and was powerful enough to militarily withstand the Pala Empire to the north-west. The last ruler of the Chandra Dynasty Govindachandra was defeated by the south Indian Emperor Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty in the 11th century.[29] Then it was under rule of Keshari dynasty of Utkal and subsequently under Ganga Dynasty of Kalinga followed by Surya dynasty of Kalinga till 1568 CE.

Sena Empire

The Pala dynasty was followed by the Sena dynasty which hailed from south India; they and their feudatories are referred to in history books as the "Kannada kings." In contrast to the Pala dynasty who championed Buddhism, the Sena dynasty were staunchly Hindu. They brought about a revival of Hinduism and cultivated Sanskrit literature in eastern India. They succeeded in bringing Bengal under one ruler during the 12th century. Vijaya Sena, second ruler of the dynasty, defeated the last Pala emperor, Madanapala, and established his reign formally. Ballala Sena, third ruler of the dynasty, was a scholar and philosopher king. He is said to have invited Brahmins from both south India and north India to settle in Bengal, and aid the resurgence of Hinduism in his kingdom. He married a Western Chalukya princess and concentrated on building his empire eastwards, establishing his rule over nearly all of Bengal and large areas of lower Assam. Ballala Sena made Nabadwip his capital,[30] three hundred years later, that city was to become a stronghold of the Bhakti movement of Hinduism under Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.

The fourth Sena king, Lakshmana Sena, son of Ballala Sena, was the greatest king of his line. He expanded the empire beyond Bengal into Bihar, Assam, Odisha and likely Varanasi. Lakshmana was later defeated by the nomadic Turkic Muslims and fled to eastern Bengal, where he ruled few more years. It is proposed by some Bengali authors that Jayadeva, the famous Sanskrit poet and author of Gita Govinda, was one of the Pancharatnas or "five Gems" of the court of Lakshmana Sena.

Deva Kingdom

The Deva Kingdom was a Hindu dynasty of medieval Bengal that ruled over eastern Bengal after the collapse Sena Empire. The capital of this dynasty was Bikrampur in present-day Munshiganj District of Bangladesh. The inscriptional evidences show that his kingdom was extended up to the present-day Comilla–Noakhali–Chittagong region. A later ruler of the dynasty Ariraja-Danuja-Madhava Dasharatha-Deva extended his kingdom to cover much of East Bengal.[31] The end of this dynasty is not yet known.

Medieval Bengal

Islam made its first appearance in Bengal during the 12th century when Sufi missionaries arrived. Later, occasional Muslim conquerors reinforced the process of conversion by building mosques, madrassas and Sufi Khanqah. Beginning in 1202 a military commander from the Delhi Sultanate, Bakhtiar Khilji, overran Bihar and Bengal as far east as Rangpur, Bogra and the Brahmaputra River. Although he failed to bring Bengal under his control, the expedition managed to defeat Lakshman Sen and his two sons moved to a place then called Bikrampur (present-day Munshiganj District), where their diminished dominion lasted until the late 13th century.

Lalbagh Fort, an intrinsic part of the history of Bengal, founded by Muhammad Azam Shah in 1678.

Lalbagh Fort, an intrinsic part of the history of Bengal, founded by Muhammad Azam Shah in 1678.

The Mosque City of Bagerhat has more than 50 Islamic monuments. The site has been recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983, "as an outstanding example of an architectural ensemble which illustrates a significant stage in human history",[34] of which the Sixty Pillar Mosque, constructed with 60 pillars and 77 domes, is the best known.[35][36]

During the 14th century, the former kingdom became known as the Sultanate of Bengal and they ruled intermittently with the Sultanate of Delhi for the next 200 years .

Ilyas Shahi dynasty

Shamsuddin Iliyas Shah founded the dynasty. It lasted from 1342–1487. The dynasty successfully repulsed attempts by Delhi to conquer them. They continued to reel in the territory of modern-day Bengal, reaching to Khulna in the south and Sylhet in the east. The sultans advanced civic institutions and became more responsive and "native" in their outlook and cut loose from Delhi. Considerable architectural projects were completed including the massive Adina Mosque and the Darasbari Mosque which still stands in Bangladesh. The Sultans of Bengal were patrons of Bengali literature and began a process in which Bengali culture and identity would flourish. The Ilyas Shahi Dynasty was interrupted by an uprising by the Hindus under Raja Ganesha. However the Ilyas Shahi dynasty was restored by Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah.

Ganesha dynasty

The Ganesha dynasty began with Raja Ganesha in 1414. After Raja Ganesha seized control over Bengal, he faced an imminent threat of invasion. Ganesha appealed to a powerful Muslim holy man named Qutb al Alam to stop the threat. The saint agreed on the condition that Raja Ganesha's son, Jadu, would convert to Islam and rule in his place. Raja Ganesha agreed and Jadu started ruling Bengal as Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah in 1415.

Qutb al Alam died in 1416 and Raja Ganesha was emboldened to depose his son and return to the throne as Danujamarddana Deva. Jalaluddin was reconverted to Hinduism by the Golden Cow ritual. After the death of his father Jalaluddin once again converted to Islam and started ruling again.[37] Jalaluddin's son, Shamsuddin Ahmad Shah ruled for only 3 years due to chaos and anarchy. The dynasty is known for its liberal policies as well as its focus on justice and charity.

Hussain Shahi dynasty

The Hussain Shahi dynasty ruled in the period 1494–1538. Alauddin Hussain Shah, considered as the greatest of all the sultans of Bengal for bringing cultural renaissance during his reign. He extended the sultanate all the way to the port of Chittagong, which witnessed the arrival of the first Portuguese merchants. Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah gave refuge to the Afghan lords during the invasion of Babur though he remained neutral. However Nusrat Shah made a treaty with Babur and saved Bengal from a Mughal invasion. The last Sultan of the dynasty, who continued to rule from Gaur, had to contend with rising Afghan activity on his northwestern border. Eventually, the Afghans broke through and sacked the capital in 1538 where they remained for several decades until the arrival of the Mughals.

Early Modern Bengal

Mughal period

In 1534, the Afghan Sher Shah Suri, or Farid Khan – a man of incredible military and political skill – succeeded in defeating the superior forces of the Mughals under Humayun at Chausa (1539) and Kannauj (1540). Sher Shah fought back and captured both Delhi and Agra and established a kingdom stretching far into Punjab. Sher Shah's administrative skill showed in his public works, including the Grand Trunk Road connecting Sonargaon in Bengal with Peshawar in the Hindu Kush. Sher Shah's rule ended with his death in 1545, although even in those five years his reign would have a powerful influence on Indian society, politics, and economics. Shah Suri's successors lacked his administrative skill, and quarrelled over the domains of his empire. Humayun, who then ruled a rump Mughal state, saw an opportunity and in 1554 seized Lahore and Delhi.

Emperor Humayun died in January 1556. Around same time, Hemu, also called Hema Chandra Vikramaditya, the then Hindu Prime Minister-cum-Chief of Army, of the Sur dynasty won Bengal in the 'battle at Chapperghatta', killing Muhammad Shah the then ruler of Bengal. This was Hemu's 20th continuous win in North India. Knowing of Humanyun's death, Hemu found a God given opportunity to win Delhi for himself and rushed to Delhi to win Agra and later on Delhi, defeated Akbar's forces at both the places, and established 'Hindu Raj' in North India on 6 Oct 1556, after 300 years of Muslim rule, leaving Bengal to his Governor Shahbaz Khan.

Akbar, the greatest of the Mughal emperors, defeated the Karani rulers of Bengal in 1576. Afterwards, Bengal came once more under the control of Delhi. It became a Mughalsubah and ruled through subahdars (governors). Akbar exercised progressive rule and oversaw a period of prosperity (through trade and development) in Bengal and northern India.

Bengal's trade and wealth impressed the Mughals that they called the region the "Paradise of the Nations". Administration by governors appointed by the court of the Mughal Empire court (1575–1717) gave way to four decades of semi-independence under the Nawabs of Murshidabad, who respected the nominal sovereignty of the Mughals in Delhi. The Nawabs granted permission to the French East India Company to establish a trading post at Chandernagore in 1673, and the British East India Company at Calcutta in 1690.

- Economy

Under the Mughal Empire, Bengal was an affluent province with a Muslim majority and Hindu minority, and was globally dominant in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding.[8][9][10] The capital Dhaka had a population exceeding a million people, and with an estimated 80,000 skilled textile weavers. It was an exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpeter, and agricultural and industrial produce.[7]

Bengali farmers and agriculturalists were quick to adapt to profitable new crops between 1600 and 1650. Bengali agriculturalists rapidly learned techniques of mulberry cultivation and sericulture, establishing Bengal as a major silk-producing region of the world.[38]

Under Mughal rule, Bengal was a center of the worldwide muslin, silk and pearl trades.[39] During the Mughal era, the most important center of cotton production was Bengal, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets such as Central Asia.[40] Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles. Overseas, Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and opium; Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, for example, including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks.[41] From Bengal, saltpeter was also shipped to Europe, opium was sold in Indonesia, raw silk was exported to Japan and the Netherlands, and cotton and silk textiles were exported to Europe, Indonesia and Japan.[42]

Bengal had a large shipbuilding industry. In terms of shipbuilding tonnage during the 16th–18th centuries, the annual output of Bengal alone totaled around 2,232,500 tons, larger than the combined output of the Dutch (450,000–550,000 tons), the British (340,000 tons), and North America (23,061 tons).[43]

Hindu Raj

There were several independent Hindu states established in Bengal during the Mughal period like those of Maharaja Pratap Aditya of Jessore and Raja Sitaram Ray of Burdwan, Raja Krishnachandra Roy of Nadia Raj and Kingdom of Mallabhum. These kingdoms contributed a lot to the economic and cultural landscape of Bengal. Extensive land reclamations in forested and marshy areas were carried out and intrastate trade as well as commerce were highly encouraged. These kingdoms also helped introduce new music, painting, dancing and sculpture into Bengali art-forms as well as many temples were constructed during this period. Militarily, they served as bulwarks against Portuguese and Burmese attacks.

- Kingdom of Bhurshut

The Kingdom of Bhurshut was a medieval Hindu kingdom spread across what is now Howrah and Hooghly in the Indian state of West Bengal. Maharaja Rudranarayan consolidated the dynasty and expanded the kingdom and converted it into one of the most powerful Hindu kingdom of the time. His wife Maharani Bhavashankari defeated the Pathan resurgence in Bengal[44] and her reign brought power, prosperity and grandeur to Bhurishrestha Kingdom. Their son, Maharaja Pratapnarayan, patronised literature and art, trade & commerce, as well as welfare of his subjects. Afterwards, Maharaja Naranarayan maintained the integrity and sovereignty of the kingdom by diplomatically averting the occupation of the kingdom by the Mughal forces. His son, Maharaja Lakshminarayan, failed to maintain the sovereignty of the kingdom due to sabotage from within.

- Koch Bihar Kingdom

The Koch Bihar Kingdom in the northern Bengal, flourished during the period of 16th and the 17th centuries as well as weathered the Mughals and survived till the advent of the British.[45]

- Burdwan Raj

The Burdwan Raj was a zamindari estate that flourished from about 1657 to 1955, first under the Mughals and then under the British in the province of Bengal in British-India. At the peak of its prosperity in the 18th century, the estate extended to around 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of territory[46] and even up to the early 20th century paid an annual revenue to the government in excess of 3,300,000 rupees.

Nawabs of Bengal

The Nawabs of Bengal and Murshidabad were the rulers of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. Between 1717 and 1757, they served as the heads of state of the sovereign Principality of Bengal. The position was established as the hereditary Nazims or Subahdars (provincial governors) of the subah (province) of Bengal during the Mughal rule and later became the independent rulers of the region. A centre of rice cultivation, fine cotton such as muslin, ship building, and the world's main source of jute fibre, Bengal was one of the world's principal centres of industry during this time.[47]

Jagat Seth

The Jagat Seths were a rich business and Money lender family in Murshidabad, Bengal during the time of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula. The Seths were among the most powerful bankers of India during the first half of 18th century. Roben Orme (official historian of East India Company) described Jagat Seths as the greatest shroff (money changer) and banker in the known world.[48]

According to Nick Robins:[49] The Jagat Seths were unrivalled in northern India for their financial power. Known as 'banker of the world', this Marwari family had build up formidable economic resources on the back of its control of the imperial mint and extensive moneylending. They wielded this financial clout at the Bengali court and were judged to be 'the chief cause of revolutions in Bengal' by a French commentator at the time.

Maratha invasions

Around the early 18th century, the Maratha Empire led invasions of Bengal. The leader of the expedition was Maratha Maharaja Raghuji of Nagpur. Raghoji was able to annexe Odisha and parts of Bengal permanently as he successfully exploited the chaotic conditions prevailing in the region after the death of their Governor Murshid Quli Khan in 1727.[50]

During their occupation, the Marathas perpetrated a massacre against the local population,[51] killing close to 400,000 people in western Bengal and Bihar.[52] This devastated Bengal's economy, as many of the people killed in the Maratha raids included merchants, textile weavers,[52] silk winders, and mulberry cultivators.[53] The Cossimbazar factory reported in 1742, for example, that the Marathas burnt down many of the houses where silk piece goods were made, along with weavers' looms.[52]

Modern Bengal

Establishment of English Trade in Bengal

British East India Company

When the East India Company began strengthening the defences at Fort William (Calcutta), the Nawab, Siraj Ud Daulah, at the encouragement of the French, attacked. Under the leadership of Robert Clive, British troops and their local allies captured Chandernagore in March 1757 and seriously defeated the Nawab on 23 June 1757 at the Battle of Plassey, when the Nawab's soldiers betrayed him. The Nawab was assassinated in Murshidabad, and the British installed their own Nawab for Bengal and extended their direct control in the south. Chandernagore was restored to the French in 1763. The Bengalis attempted to regain their territories in 1765 in alliance with the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, but were defeated again at the Battle of Buxar (1765). The centre of Indian culture and trade shifted from Delhi to Calcutta when the Mughal Empire fell.

The plunder of Bengal directly contributed to the Industrial Revolution in Britain,[8][9][10][11] with the capital amassed from Bengal used to invest in British industries such as textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution and greatly increase British wealth, while at the same time leading to deindustrialization and famines in Bengal.[8][9][10]

British rule

During British rule, two devastating famines occurred costing millions of lives in 1770 and 1943. Scarcely five years into the British East India Company's rule, the catastrophic Bengal famine of 1770, one of the greatest famines of history occurred. Up to a third of the population died in 1770 and subsequent years. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 replaced rule by the Company with the direct control of Bengal by the British Crown.

A centre of rice cultivation as well as fine cotton called muslin and the world's main source of jute fibre, Bengal was one of India's principal centres of industry, and from the 1850s became concentrated in the capital Kolkata (known as Calcutta under the British, always called 'Kolkata' in the native tongue of Bengali) and its emerging cluster of suburbs. Most of the population nevertheless remained dependent on agriculture, and despite its leading role in Indian political and intellectual activity, the province included some very undeveloped districts, especially in the east. In 1877, when Victoria took the title of "Empress of India", the British declared Calcutta the capital of the British Raj.

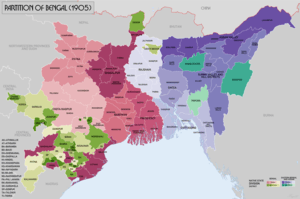

India's most popular province (and one of the most active provinces for independence activities), in 1905 Bengal was divided by the British rulers for administrative purposes into an overwhelmingly Hindu west (including present-day Bihar and Odisha) and a predominantly Muslim east (including Assam) (1905 Partition of Bengal). Hindu – Muslim conflict became stronger through this partition. While Hindu Indians disagreed with the partition saying it was a way of dividing a Bengal which is united by language and history, Muslims supported it by saying it was a big step forward for Muslim society where Muslims will be majority and they can freely practice their religion as well as their culture. But owing to strong Hindu agitation, the British reunited East and West Bengal in 1912, and made Bihar and Orissa a separate province. Another major famine occurred during the second world war, the Bengal famine of 1943, in which an estimated 3 million people died.

Bengal Renaissance

Raja Ram Mohan Roy is regarded as the "Father of the Bengali renaissance."

Raja Ram Mohan Roy is regarded as the "Father of the Bengali renaissance." Rabindranath Tagore is Asia's first Nobel laureate, composer of India's national anthem and Bangladesh's national anthem, while inspired Sri Lankan national anthem.

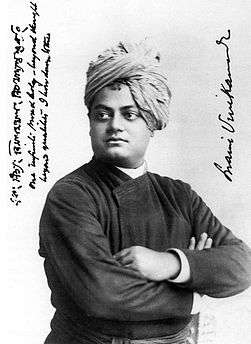

Rabindranath Tagore is Asia's first Nobel laureate, composer of India's national anthem and Bangladesh's national anthem, while inspired Sri Lankan national anthem. Swami Vivekananda was a key figure in introducing Vedanta and Yoga in the Western world,[54] raising interfaith awareness and making Hinduism a world religion.[55]

Swami Vivekananda was a key figure in introducing Vedanta and Yoga in the Western world,[54] raising interfaith awareness and making Hinduism a world religion.[55]- Jagadish Chandra Bose was a physicist, biologist, botanist, archaeologist, and writer of science fiction.[56] He pioneered the investigation of radio and microwave optics, made very significant contributions to plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the Indian subcontinent.[57] He is considered one of the fathers of radio science,[58] and is also considered the father of Bengali science fiction.

Satyendra Nath Bose was a physicist, specialising in mathematical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, providing the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate. He is honoured as the namesake of the boson.

Satyendra Nath Bose was a physicist, specialising in mathematical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, providing the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate. He is honoured as the namesake of the boson.

The Bengal Renaissance refers to a social reform movement during the 19th and early 20th centuries in the region of Bengal in undivided India during the period of British rule. The Bengal renaissance can be said to have started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833) and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), although there have been many stalwarts thereafter embodying particular aspects of the unique intellectual and creative output.[59] 19th century Bengal was a unique blend of religious and social reformers, scholars, literary giants, journalists, patriotic orators and scientists, all merging to form the image of a renaissance, and marked the transition from the 'medieval' to the 'modern'.[60]

Independence movement

Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement, in which revolutionary groups such as Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar were dominant. Bengalis also played a notable role in the Indian independence movement. Many of the early proponents of independence, and subsequent leaders in movement were Bengalis such as Chittaranjan Das, Surendranath Banerjee, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Prafulla Chaki, Bagha Jatin, Khudiram Bose, Surya Sen, Binoy–Badal–Dinesh, Sarojini Naidu, Aurobindo Ghosh, Rashbehari Bose and many more. Some of these leaders, such as Netaji, did not subscribe to the view that non-violent civil disobedience was the only way to achieve Indian Independence, and allied with Japan to fight against the British. During the Second World War Netaji escaped to Germany from house arrest in India and there he founded the Indian Legion an army to fight against the British Government, but the turning of the war compelled him to come to South-East Asia and there he became the co-founder and leader of the Indian National Army (distinct from the army of British India) that challenged British forces in several parts of India. He was also the head of state of a parallel regime named 'The Provisional Government of Free India' or Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind, that was recognised and supported by the Axis powers. Bengal was also the fostering ground for several prominent revolutionary organisations, the most notable of which was Anushilan Samiti. A large number of Bengalis died in the independence struggle and many were exiled in Cellular Jail, the much dreaded prison located in Andaman.

Partitions of Bengal

In the 20th century, the partitions of Bengal, occurring twice, has left great marks on the history and psyche of the people of Bengal. The first partition occurred in 1905 and the second partition was in 1947. As partition of British India into Hindu and Muslim dominions approached in 1947, Bengal again was divided into the state of West Bengal of India and the province of East Bengal under Pakistan, renamed East Pakistan in 1958.

The partition of Bengal entailed the greatest exodus of people in human history. Millions of Hindus migrated from East Pakistan to India and thousands of Muslims too went across the borders to East Pakistan. Because of the coming of the refugees, there occurred the crisis of land and food in West Bengal; and such condition remained in long duration for more than three decades. The politics of West Bengal since the partition in 1947 developed round the nucleus of refugee problem. Both the Rightists and the Leftists in politics of West Bengal have not yet become free from the socio-economic conditions created by the partition of Bengal.

Present Bengal

East Pakistan (East Bengal) rebelled against Pakistani military rule to become independent republic of Bangladesh (meaning: 'Country of Bengal') after a war of independence against the Pakistani army in 1971. West Bengal remains a part of India.

See also

References

- ↑ "History of Bangladesh". Bangladesh Student Association. Archived from the original on 19 December 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- 1 2 http://www.gutenberg-e.org/yang/pdf/yang-chapter2.pdf

- ↑ Suhrawardi, Ghulam M. (2015). Bangladesh Maritime History. FriesenPress. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-1-4602-7278-7.

- ↑ "Silk Road and Muslin Road".

- ↑ Ghosh, Binoy, Paschim Banger Sanskriti, (in Bengali), part II, 1976 edition, pp. 218–234, Prakash Bhaban

- ↑ "Isa Khan – Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2016-03-27.

- 1 2 3 "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Opinion).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Junie T. Tong (2016), Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets, page 151, CRC Press

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 John L. Esposito (2004), The Islamic World: Past and Present 3-Volume Set, page 190, Oxford University Press

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857), Routledge, ISBN 1136825525

- 1 2 Shombit Sengupta, Bengals plunder gifted the British Industrial Revolution, The Financial Express, February 8, 2010

- ↑ James Heitzman and Robert L. Worden, ed. (1989). "Early History, 1000 B. C.-A. D. 1202". Bangladesh: A country study. Library of Congress.

- ↑ Ahmed, Helal Uddin (2012). "History". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ RIYAZU-S-SALĀTĪN: A History of Bengal, Ghulam Husain Salim, The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1902.

- ↑ India: A History by John Keay p.220

- ↑ The Cambridge Shorter History of India p.145

- ↑ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.281

- ↑ Land of Two Rivers, Nitish Sengupta

- ↑ Sarkar, Sebanti (28 March 2008). "History of Bengal just got a lot older" (jsp). The Daily Telegraph. Kolkata: The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

Humans walked on Bengal's soil 20,000 years ago, archaeologists have found out, pushing the state's pre-history back by some 8,000 years.

- ↑ Bharadwaj, G (2003). "The Ancient Period". In Majumdar, RC. History of Bengal. B.R. Publishing Corp.

- ↑ http://www.paxgaea.com/HRBangladesh.html

- 1 2 Momtazur Rahman Tarafdar, "Itihas O Aitihasik", Bangla Academy Dhaka, 1995

- 1 2 3 O’Malley, L.S.S., ICS, Bankura, Bengal District Gazetteers, pp. 21–46, 1995 reprint, first published 1908, Government of West Bengal

- ↑ Östör, Ákos (9 September 2015). Play Of The Gods: Locality, Ideology, Structure, And Time In The Festivals Of A Bengali Town. Orient Blackswan. p. 43. ISBN 81-8028-013-6.

- ↑ Pandey, Dr.S.N. (1 September 2010). West Bengal General Knowledge Digest. Upkar Prakashan. p. 28. ISBN 9788174822826. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ App, Urs. The Birth of Orientalism. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 302. ISBN 0812200055. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib by Nitish K. Sengupta p.45

- 1 2 The Cambridge Shorter History of India p.10

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of North-East India by T. Raatan p.143

- ↑ Nadia' Jillar Purakirti by Archaeological Survey of India, West Bengal, 1975

- ↑ Roy, Niharranjan (1993). Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba Calcutta: Dey's Publishing, ISBN 81-7079-270-3, pp.408–9

- ↑ Travel:Dinajpur, from Bangladesh Online (ISP).

- ↑ Ahmed, Nazimuddin (2012). "Kantanagar Temple". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ "Historic Mosque City of Bagerhat". unesco.org. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Leung, Mikey; Meggitt, Belinda (1 November 2009). Bangladesh. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-84162-293-4. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Brennan, Morgan; Cerone, Michelle. "In Pictures: 15 Lost Cities of the World". Forbes.com. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Biographical encyclopedia of Sufis By N. Hanif, pg.320

- ↑ John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 190, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Lawrence B. Lesser. "Historical Perspective". A Country Study: Bangladesh (James Heitzman and Robert Worden, editors). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (September 1988). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.About the Country Studies / Area Handbooks Program: Country Studies - Federal Research Division, Library of Congress

- ↑ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760, page 202, University of California Press

- ↑ Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237-240, World History in Context, accessed 3 August 2017

- ↑ John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 202, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Ray, Indrajit (2011), Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857), page 174, Routledge, ISBN 1136825525

- ↑ Ghosh, Paschimbanger Sanskriti, Volume II, pp. 224

- ↑ Ghosh, Dr. Sujit (2016). Colonial Economy in North Bengal: 1833–1933. Kolkata: Paschimbanga Anchalik Itihas O Loksanskriti Charcha Kendra. p. 101. ISBN 978-81-926316-6-0.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India, New Edition (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908–1931), Vol. 9, p. 102

- ↑ Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution. Routledge. ISBN 1136825525.

- ↑ Entrepreneurial networks and business culture By Clara Eugenia Núñez, Michael S. Moss,p 94

- ↑ Nick Robins, The Corporation Which Changed The World, Pluto Press, 2006

- ↑ SNHM. Vol. II, pp. 209, 224.

- ↑ P. J. Marshall (2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–73.

- 1 2 3 Kirti N. Chaudhuri (2006). The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660-1760. Cambridge University Press. p. 253.

- ↑ P. J. Marshall (2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. p. 73.

- ↑ Georg, Feuerstein (2002), The Yoga Tradition, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, p. 600

- ↑ Clarke, Peter Bernard (2006), New Religions in Global Perspective, Routledge, p. 209

- ↑ A versatile genius Archived 3 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine., Frontline 21 (24), 2004.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Santimay and Chatterjee, Enakshi, Satyendranath Bose, 2002 reprint, p. 5, National Book Trust, ISBN 81-237-0492-5

- ↑ Sen, A. K. (1997). "Sir J.C. Bose and radio science". Microwave Symposium Digest. IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium. Denver, CO: IEEE. pp. 557–560. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602854. ISBN 0-7803-3814-6.

- ↑ History of the Bengali-speaking People by Nitish Sengupta, p 211, UBS Publishers' Distributors Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-7476-355-4.

- ↑ Calcutta and the Bengal Renaissance by Sumit Sarkar in Calcutta, the Living City edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, Vol I, p 95.

Further reading

- Salim, Gulam Hussain; tr. from Persian; Abdus Salam (1902). Riyazu-s-Salatin: History of Bengal. Asiatic Society, Baptist Mission Press.

- Majumdar, R. C. The History of Bengal ISBN 81-7646-237-3

- Amiya Sen (1993). Hindu Revivalism in Bengal 1872–1905: Some Essays in Interpretation. Oxford University Press.

- Abdul Momin Chowdhury (1967) Dynastic History of Bengal, c. 750–1200 A.D, Dacca: The Asiatic Society of Pakistan, 1967, Pages: 310, ASIN: B0006FFATA

- Iftekhar Iqbal (2010) The Bengal Delta: Ecology, State and Social Change, 1840–1943, Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies, Palgrave Macmillan, Pages: 288, ISBN 0230231837

- M. Mufakharul Islam (edited) (2004) Socio-Economic History of Bangladesh: essays in memory of Professor Shafiqur Rahman, 1st Edition, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, OCLC 156800811

- M. Mufakharul Islam (2007), Bengal Agriculture 1920–1946: A Quantitative Study, Cambridge South Asian Studies, Cambridge University Press, Pages: 300, ISBN 0521049857

- Meghna Guhathakurta & Willem van Schendel (Edited) (2013) The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics (The World Readers), Duke University Press Books, Pages: 568, ISBN 0822353040

- Sirajul Islam (edited) (1997) History of Bangladesh 1704–1971(Three Volumes: Vol 1: Political History, Vol 2: Economic History Vol 3: Social and Cultural History), 2nd Edition (Revised New Edition), The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Pages: 1846, ISBN 9845123376

- Sirajul Islam (Chief Editor) (2003) Banglapedia: A National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh.(10 Vols. Set), (written by 1300 scholars & 22 editors) The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Pages: 4840, ISBN 9843205855

- Samares Kar: The Millennia Long Migration into Bengal: Rich Genetic Material and Enormous Promise in the Face of Chaos, Corruption, and Criminalization. In: Spaces & Flows: An International Journal of Urban & Extra Urban Studies. Vol. 2 Issue 2, 2012, S. 129–143 (Fulltext see ResearchGate Network).

- Dr. Sujit Ghosh, (2016) Colonial Economy in North Bengal: 1833–1933, Kolkata: Paschimbanga Anchalik Itihas O Loksanskriti Charcha Kendra, ISBN 978-81-926316-6-0