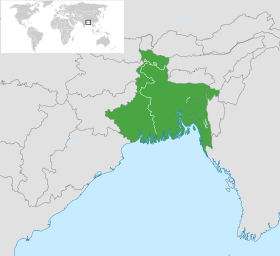

United Bengal

United Bengal is a political ideology for a unified Bengali-speaking nation in South Asia. The ideology developed among Bengali nationalists after the first partition of Bengal in 1905. The British-ruled Bengal Presidency was divided into Western Bengal and Eastern Bengal and Assam to weaken the independence movement; after much protest Bengal was reunited in 1911.

The United Bengal proposal was the bid made by the Bengali Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and nationalist leader Sarat Chandra Bose to found a united and independent nation-state of Bengal.[1][2] The proposal was floated as an alternative to the partition of Bengal on communal lines. The initiative failed owing to British diplomacy and communal conflict between Muslims and Hindus that eventually led to the second partition of Bengal.

History

As the Hindu-Muslim conflict escalated and the demand for a separate Muslim state of Pakistan became popular among Indian Muslims, the partition of India on communal lines was deemed inevitable by mid-1947. To prevent the inclusion of Hindu-majority districts of Punjab and Bengal in a Muslim Pakistan, the Indian National Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha sought the partition of these provinces on communal lines. Bengali nationalists such as Sarat Chandra Bose, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Kiran Shankar Roy, Abul Hashim, Satya Ranjan Bakshi and Fazlul Qadir Chaudhry sought to counter partition proposals with the demand for a united and independent state of Bengal.[3][4] In a press statement on 27 April 1947 Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy said:

Let us pause for a moment to consider what Bengal can be if it remains united. It will be a great country, indeed the richest and the most prosperous in India capable of giving to its people a high standard of living, where a great people will be able to rise to the fullest height of their stature, a land that will truly be plentiful. It will be rich in agriculture, rich in industry and commerce and in course of time it will be one of the powerful and progressive states of the world. If Bengal remains united this will be no dream, no fantasy.[5]

Ideological visions for a “Greater Bengal” included the regions of Northeast India. Suhrawardy and Bose sought the formation of a coalition government between the Bengali Congress and the Bengal Provincial Muslim League. Proponents of the plan urged the masses to reject communal divisions and uphold the vision of a united Bengal. In a press conference held in Delhi on April 27, 1947, Suhrawardy presented his plan for a united and independent Bengal and Abul Hashim issued a similar statement in Calcutta on April 29. A few days later, Sarat Chandra Bose put forward his proposals for a "Sovereign Socialist Republic of Bengal."

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the President of the All-India Muslim League and later Founding Father of Pakistan, showed his support for the proposal along with Mahatma Gandhi, but the Indian National Congress aggressively opposed it. Muhammad Ali Jinnah who saw it for the benefits for Bengali Muslims.:285[6] Jinnah viewed this plan in a long term geostrategic point in believing that independent Bengal led by Muslim premier would forged a closer alliance with Pakistan than it would with India.:285[6]:6-7[7]

Proposal

With the support of the British governor of the Bengal province, Frederick Burrows, Bengali leaders issued the formal proposal on May 20:

- Bengal would be a Free State. The Free State of Bengal would decide its relations with the rest of India.[8]

- The Constitution of the Free State of Bengal would provide for election to the Bengal Legislature on the basis of a joint electorate and adult franchise, with reservation of seats proportionate to the population among Hindus and Muslims. The seats set aside for Hindus and Scheduled Caste Hindus would be distributed amongst them in proportion to their respective population, or in such manner as may be agreed among them. The constituencies would be multiple constituencies and the votes would be distributive and not cumulative. A candidate who got the majority of the votes of his own community cast during the elections and 25 percent of the votes of the other communities so cast, would be declared elected. If no candidate satisfied these conditions, that candidate who got the largest number of votes of his own community would be elected.[8]

- On the announcement by His Majesty's Government that the proposal of the Free State of Bengal had been accepted and that Bengal would not be partitioned, the present Bengal Ministry would be dissolved. A new interim Ministry would be brought into being, consisting of an equal number of Muslims and Hindus (including Scheduled Caste Hindus) but excluding the Chief Minister. In this Ministry, Chief Minister would be a Muslim and the Home Minister a Hindu.

- Pending the final emergence of a Legislature and a Ministry under the new constitutions, Hindus (including Scheduled Caste Hindus) and Muslims would have an equal share in the Services, including military and police. The Services would be manned by Bengalis.[8]

- A Constituent Assembly composed of 30 persons, 16 Muslims and 14 non-Muslims, would be elected by Muslim and non-Muslim members of the Legislature respectively, excluding Europeans.[8][9]

Failure

The proposal made no mention of Bengal's status in the Commonwealth if it were to become independent or whether it would accept dominion status as was done later with the Union of India, the Dominion of Pakistan and Ceylon or sever all ties with the United Kingdom.

Opposition

On May 12, 1947 Abul Hashim and Sarat Bose met Mahatma Gandhi to discuss the United Bengal scheme and received his blessings. However, the day afterward, on May 13, 1947, the president of the Indian National Congress, JB Kripalini, dismissed any notions to "save the unity of Bengal". In reply to the plea, made by Ashrafuddin Chowdhury, a Muslim nationalist and peasant leader from Tippera, Kripalini wrote: "All that the Congress seeks to do today is to rescue as many areas as possible from the threatened domination of the League and Pakistan. It wants to save as much territory for a Free Indian Union as is possible under the circumstances. It therefore insists upon the division of Bengal and Punjab into areas for Hindustan and Pakistan respectively".[4][10]

The Muslim League and the Congress issued statements rejecting the notion of an independent Bengal on May 28 and June 1 respectively. The communists also rejected such notions[3] According to Mountbatten, Jinnah agreed to the proposal of a United Bengal until Nehru and Patel rejected it, when Jinnah agreed to the division of Bengal. Madhuri Bose, the niece of Sarat and Subhas Chandra Bose claimed that Jinnah agreed to reconsider his partition plan, if Sarat and Subhas Chandra Bose took over the leadership of the Indian National Congress.[9]

When the Congress agreed to the partition of Punjab, the Hindu Mahasabha, fearing a Muslim majority, dropped its aspirations for a United India and started to oppose the notion of independent Bengal fierecely.[11] Bengali Muslim leader Khawaja Nazimuddin and Maulana Akram Khan sought the exclusion of Hindu-majority areas to establish a homogeneous Muslim Pakistan.

With aggravating Hindu-Muslim tensions and the opposition of the Congress and Muslim League leadership, on June 3 British viceroy Lord Louis Mountbatten announced plans to partition India and consequently Punjab and Bengal on communal lines, burying the demand for an independent Bengal.[8]

Legacy

In 2016, Madhuri Bose, niece of Sarat and Subhas Chandra Bose claimed in her book ''The Bose Brothers", Sarat Bose held the Congress more responsible of the failure of the idea than the Muslim League since Jinnah was a supporter of the proposal.[9]

References

- ↑ Christophe Jaffrelot (2004). A History of Pakistan and Its Origins. Anthem Press. p. 42. ISBN 9781843311492.

- ↑ "Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy : His Life". thedailynewnation.com. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- 1 2 Mukhopadhay, Keshob. "An interview with prof. Ahmed sharif". News from Bangladesh. Daily News Monitoring Service. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- 1 2 Kabir, Nurul (1 September 2013). "Colonialism, politics of language and partition of Bengal PART XVI". The New Age. The New Age. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ↑ "Text of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy's Press Statement in 27 April 1947 ( United Bengal )". BangladeshBD.org. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- 1 2 Ahmed, Salahuddin (2004). "§United Bengal Plan and Role of Jinnah". Bangladesh: Past and Present (google books) (1st ed.). Delhi, India: APH Publishing. p. 351. ISBN 9788176484695. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ↑ Dowlah, Caf (2016). "Introduction". The Bangladesh Liberation War, the Sheikh Mujib Regime, and Contemporary Controversies (google books). Indiana, U.S.: Lexington Books. p. 191. ISBN 9781498534192. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Misra, Chitta Ranjan. "United Bengal Movement". Banglapedia. Bangladesh Asiatic Society. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Book by Madhuri Bose throws new light on 'United Bengal' plan". BDNews24.com. BDNews24.com. 28 January 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ Bose, Sugata (1987). Agrarian Bengal: Economy, Social Structure and Politics: 1919-1947. Hyderabad: Cambridge University Press, First Indian Edition in association with Orient Longman,. pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2009). Decolonization in South Asia: Meanings of Freedom in Post-independence West Bengal, 1947–52. Routledge.