Anushilan Samiti

| |

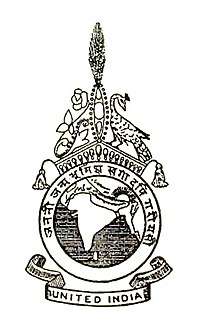

| Motto | United India |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1902 |

| Type | Secret Revolutionary Society |

| Purpose | Indian Independence |

Anushilan Samiti (Ōnūshīlōn sōmītī, lit: body-building society) was a Bengali Indian organisation that existed in the first quarter of the twentieth century, and propounded revolutionary violence as the means for ending British rule in India. The organisation arose from a conglomeration of local youth groups and gyms (Akhara) in Bengal in 1902. It had two prominent, if somewhat independent, arms in East and West Bengal identified as Dhaka Anushilan Samiti centred in Dhaka (modern day Bangladesh), and the Jugantar group (centred at Calcutta) respectively.

From its foundation to its gradual dissolution during the 1930s, the Samiti challenged British rule in India by engaging in militant nationalism, including bombings, assassinations, and politically-motivated violence. During its existence, the Samiti collaborated with other revolutionary organisations in India and abroad. It was led by nationalists such as Aurobindo Ghosh and his brother Barindra Ghosh, and influenced by philosophies as diverse as Hindu Shakta philosophy propounded by Bengali literaetuer Bankim and Vivekananda, Italian Nationalism, and Pan-Asianism of Kakuzo Okakura. The Samiti was involved in a number of noted incidences of revolutionary terrorism against British interests and administration in India within the decade of its founding, including early attempts to assassinate Raj officials whilst led by the Ghosh brothers. These were followed by the 1912 attempt on the life of the Viceroy of India, and the Sedetious conspiracy during World War I led by Rash Behari Bose and Jatindranath Mukherjee respectively.

The organisation moved away from its philosophy of violence in the 1920s, when a number of its members identified closely with the Congress and Gandhian non-violent movement, but a section of the group, notably under Sachindranath Sanyal, remained active in revolutionary movement, founding the Hindustan Republican Association in north India. A number of Congress leaders from Bengal, especially Subhash Chandra Bose, were accused by the British Government of having links with, and allowing patronage to, the organisation during this time.

The organisation's violent and radical philosophy revived in the 1930s, when it was involved in the Kakori conspiracy, the Chittagong armoury raid, and other attempts against the administration in British India and Raj officials.

Shortly after its inception, the organisation became the focus of an extensive police and intelligence operation which led to the founding of the Special branch of the Calcutta Police. Notable officers who led the police and intelligence operations against the Samiti at various times included Sir Robert Nathan, Sir Harold Stuart, Sir Charles Stevenson-Moore and Sir Charles Tegart. The threat posed by the activities of the Samiti in Bengal during World War I, along with the threat of a Ghadarite uprising in Punjab, led to the passage of Defence of India Act 1915. These measures enabled the arrest, internment, transportation and execution of a number of revolutionaries linked to the organisation, which crushed the East Bengal Branch. In the aftermath of the war, the Rowlatt committee recommended extending the Defence of India Act (as the Rowlatt Act) to thwart any possible revival of the Samiti in Bengal and the Ghadarite movement in Punjab. After the war, the activities of the party led to implementation of the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment in the early 1920s, which reinstated the powers of incarceration and detention from the Defence of India Act. However, the Anushilan Samiti gradually disseminated into the Gandhian movement. Some of its members left for the Indian National Congress then led by Subhas Chandra Bose, while others identified more closely with Communism. The Jugantar branch formally dissolved in 1938. In independent India, the party in West Bengal evolved into the Revolutionary Socialist Party, while the Eastern Branch later evolved into the Shramik Krishak Samajbadi Dal (Workers and Peasants Socialist Party) in present-day Bangladesh.

Background

The growth of the Indian middle class during the 18th century, amidst competition among regional powers and the ascendancy of the British East India Company, led to a growing sense of "Indian" identity.[1] The refinement of this perspective fed a rising tide of nationalism in India in the last decades of the 1800s.[2] Its speed was abetted by the creation of the Indian National Congress in India in 1885 by A.O. Hume. The Congress developed into a major platform for the demands of political liberalisation, increased autonomy and social reform.[3] However, the nationalist movement became particularly strong, radical and violent in Bengal and, later, in Punjab. Notable, if smaller, movements also appeared in Maharashtra, Madras and other areas in the South.[3] The movement in Maharshtra, especially Bombay and Poona preceded most revolutionary movements in the country. This movement, further, had the ideological, and by some suggestion covert but active, support of Bal Gangadhar Tilak. 1876 saw the foundation of The Indian Association in Calcutta under the leadership of Surendranath Banerjea. This organisation successfully drew into its folds students and the urban middle–class, for which it served as a mouthpiece. The Association became the mouthpiece of an informal constituency of students and middle-class gentlemen. It sponsored the Indian National Conference in 1883 and 1885, which later merged with the Indian National Congress.[4] Calcutta was at the time the most prominent centre for organised politics, and some of the same students who attended the political meetings began at the time to organise "secret societies" which cultivated a cultural of physical strength and nationalist feelings.

Timeline

Origins

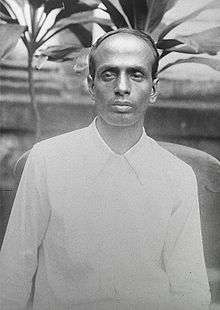

By 1902, Calcutta had three secret societies working toward the violent overthrow of British rule in India. One was founded by Calcutta student Satish Chandra Basu with the patronage of Calcutta barrister Pramatha Mitra, another was led by Bengali woman Sarala Devi and the third was founded by Aurobindo Ghosh. Ghosh was one of the strongest proponents of militant Indian nationalism at the time.[5][6] By 1905 the work of Aurobindo and his brother, Barin, enabled Anushilan Samity to spread throughout Bengal. Nationalist writings and publications by Aurobindo and Barin, including Bande Mataram and Jugantar, had a widespread influence on Bengal youth. The 1905 partition of Bengal stimulated radical nationalist sentiments in Bengal's Bhadralok community, helping Anushilan acquire a support base of educated, politically-conscious and disaffected members of local youth societies. Its program emphasized physical training, training its recruits with daggers and lathis (bamboo staffs used as weapons). The Dhaka branch of Anushilan was led by Pulin Behari Das, and branches spread throughout East Bengal and Assam.[7] More than 500 branches were opened in eastern Bengal and Assam, linked by "close and detailed organization" to Pulin's headquarters at Dhaka. It absorbed smaller groups in the province, soon overshadowing its parent organisation in Calcutta. Branches of Dhaka Anushilan emerged in Jessore, Khulna, Faridpur, Rajnagar, Rajendrapur, Mohanpur, Barvali and Bakarganj. Estimates of Dhaka Anushilan Samiti's reach indicate a membership of 15,000 to 20,000. Within two years, Dhaka Anushilan devolved its aims from the Swadeshi to that of political terrorism.[8][9]

The organisation's political views were expressed in the journal Jugantar, founded in March 1906 by Abhinash Bhattacharya, Barindra, Bhupendranath Dutt and Debabrata Basu.[10] It soon became an organ for the radical views of Aurobindo and Anushilan leaders, and lent the name "Jugantar party" to the Calcutta group of Anushilan. Early leaders were Rash Behari Bose, Jatindranath Mukherjee and Jadugopal Mukherjee.[5] Similar messages of violent nationalism were also finding their way to the public in Aurobindo's works in journals such as Sandhya, Navashakti and Bande Mataram.

Nationalism and violence

The Dhaka Anushilan Samiti embarked on a radical program of political terrorism. It broke with the Jugantar group in West Bengal due to differences with Aurobindo's approach of slowly building a mass base for revolution. The Dhaka group saw this as slow and inadequate, and sought immediate action and results. The two branches of Anushilan engaged in dacoity to raise money, and performed a number of political assassinations at this time.[11] In December 1907, the Bengal revolutionary cell derailed a train carrying Bengal Lieutenant Governor Andrew Henderson Leith Fraser in a plot led by the Ghosh brothers. That month, the Dhaka Anushilan Samiti assassinated former Dhaka district magistrate D. C. Allen. The following year, Anushilan engineered eleven assassinations, seven attempted assassinations and explosions and eight dacoities in West Bengal. The targets of these actions included British police officials and civil servants, Indian police officers, informants, public prosecutors of political crimes and wealthy families.[12] Under Barin Ghosh's direction, Anushilan members also attempted to assassinate French colonial officials in Chandernagore who were seen as complicit with the Raj.

Anushilan established early links with foreign movements and Indian nationalists abroad. In 1907 Barin Ghosh sent Hem Chandra Kanungo (Hem Chandra Das) to Paris to learn bomb-making from Nicholas Safranski, a Russian revolutionary in exile.[7] Paris was also home to Madam Cama, amongst the leading figures of the Paris Indian Society and India House in London. A bomb-making manual later found its way through V.D. Savarkar to the press at India House for publication. In 1908, young recruits Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki were sent on a mission to Muzaffarpur to assassinate chief presidency magistrate D. H. Kingsford. They bombed a carriage they mistook for Kingsford's,[11] killing two Englishwomen. In the aftermath of the bombing, Bose was arrested while attempting to flee and Chaki committed suicide. Police investigation of the killings revealed the organisation's quarters at Barin's country house in Manicktala (a suburb of Calcutta) and led to a number of arrests, including Aurobindo and Barin.[11] The ensuing trial, held under tight security, led to a death sentence for Barin (later commuted to life imprisonment); others went underground. The case against Aurobindo Ghosh collapsed after the assassination of Naren Gosain, who had turned crown witness. Gosain was shot in Alipore jail by Satyendranath Basu and Kanailal Dutta, who were also being tried. Aurobindo retired from active politics after being acquitted.[13] This was followed by a 1909 Dhaka conspiracy case, which brought 44 members of the Dhaka Anushilan to trial.[14][15] Nandalal Bannerjee (the officer who arrested Kshudiram) was shot dead in 1908, followed by the assassinations of the prosecutor and informant for the Alipore case in 1909.

In the aftermath of the Manicktala conspiracy, the western Anushilan Samiti found a more-prominent leader in Bagha Jatin and emerged as the Jugantar. Jatin revitalised links between the central organisation in Calcutta and its branches in Bengal, Bihar, Orissa and Uttar Pradesh, establishing hideouts in the Sunderbans for members who had gone underground.[16] The group slowly reorganised, aided by Amarendra Chatterjee, Naren Bhattacharya and other younger leaders. Some of its younger members, including Taraknath Das, left India. Over the next two years, the organisation operated under the cover of two apparently-separate groups: Sramajeebi Samabaya (the Labourer's Cooperative) and Harry and Sons.[13] Around this time Jatin began attempting to establish contacts with the 10th Jat Regiment, garrisoned at Fort William in Calcutta, and Narendra Nath committed a number of robberies to raise money. Shamsul Alam, a Bengal police officer preparing a conspiracy case against the group, was assassinated by Jatin associate Biren Dutta Gupta. His assassination led to the arrests which precipitated the Howrah-Sibpur Conspiracy case.[17]

Anushilan's campaign continued. In 1911 Dhaka Anushilan shot dead Sub-inspector Raj Kumar and Inspector Man Mohan Ghosh, two Bengali police officers investigating unrests linked to the group, in Mymensingh and Barisal. This was followed by the assassination of CID head constable Shrish Chandra Dey in Calcutta. In February 1911 Jugantar bombed a car in Calcutta, mistaking an Englishman for police officer Godfrey Denham. Rash Behari Bose (described as "the most dangerous revolutionary in India")[18] extended the group's reach into north India, where he found work in the Indian Forest Institute in Dehra Dun. Bose forged links forming with radical nationalists in Punjab and the United Provinces, including those later connected to Har Dayal. During the 1912 transfer of the imperial capital to New Delhi, Viceroy Charles Hardinge's howdah was bombed; his mahout was killed, and Lady Hardinge was injured.[19]

World War I

With war clouds gathering in Europe, Indian nationalists at home and abroad decided to use a war with Germany for the nationalist cause. Through Kishen Singh, the Bengal revolutionary cell was introduced to Har Dayal when Dayal visited India in 1908.[20] Dayal was associated with India House, a revolutionary organisation in London then headed by V. D. Savarkar. By 1910, Dayal was working closely with Rash Behari Bose.[21] Bose, a Jugantar member working at the Forest Institute at Dehra Dun, was engaged with the revolutionary movement in Uttar Pradesh and the Punjab since October 1910.[22] After the decline of India House, Dayal moved to San Francisco after working briefly with the Paris Indian Society. In the United States, nationalism among Indian immigrants (particularly students and the working class) was gaining ground. Taraknath Das, who left Bengal for the United States in 1907, was among the Indian students who engaged in political work. In California, Dayal became a leading organiser of Indian nationalism amongst predominantly-Punjabi immigrant workers and was a key member of the Ghadar Party.

With Naren Bhattacharya, Jatin met the crown prince of Germany during the latter's 1912 visit to Calcutta and obtained an assurance that arms and ammunition would be supplied to them.[23] Jatin learned about Rash Behari's work from Niralamba Swami on a pilgrimage to Brindavan. Returning to Bengal, he began reorganising the group. Rash Behari went into hiding in Benares after the 1912 attempt on Hardinge but he met Jatin towards the end of 1913, outlining prospects for a pan-Indian revolution. In 1914 Rash Behari Bose, the Maharashtrian Vishnu Ganesh Pinglay and Sikh militants planned simultaneous troop uprisings for February 1915. In Bengal, Anushilan and Jugantar launched what has been described by historians as "... a reign of terror in both the cities and the countryside ... [which] ... came close to achieving their key goal of paralysing the administration". An atmosphere of fear encompassed the police and courts, severely affecting morale.[24] In August 1914 Jugantar seized a large amount of arms and ammunition from the Rodda Company, a Calcutta arms dealer, which were linked to robberies in Calcutta for the next two years. In 1915, only six revolutionaries were successfully tried.

The February plot and a December 1915 plot were thwarted by British intelligence. Jatin and a number of fellow revolutionaries were killed in a firefight with police at Balasore, in present-day Orissa, which brought Jugantar to an end during the war. The Defence of India Act 1915 led to widespread arrests, internmens, deportations and executions of members of the revolutionary movement. By March 1916, widespread arrests helped Bengal police crush the Dacca Anushilan Samiti in Calcutta.[25] Regulation III and the Defence of India Act were enforced throughout Bengal in August 1916. By June 1917, 705 people were under house arrest under the Act and 99 were imprisoned under Regulation III.[25] In Bengal, revolutionary violence fell to 10 incidents in 1917.[26] According to official lists, 186 revolutionaries were killed or convicted by 1918.[27] After the war the Defence of India Act was extended by the Rowlatt Acts, the passage of which was a prime target of M. K. Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement. Many revolutionaries released after the war escaped to Burma to avoid repeated incarceration.[28]

After the war

Between 1919 and 1922, the first non-cooperation movement began with the Rowlatt Satyagrahas under Gandhi and received widespread support from luminaries of the Indian independence movement. In Bengal, Jugantar agreed to a request by Chittaranjan Das (a prominent and respected leader of the Indian National Congress) to refrain from violence. Although Anushilan did not adhere to the agreement, it sponsored no major actions between 1920 and 1922 (when the first non-cooperation movement was suspended). During the next few years, Jugantar and Anushilan became active again. Resurgence of radical nationalism linked to the Samiti during the 1920s led to the passage of the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Ordinance in 1924, enacted the following year. The act restored extraordinary powers of detention to the police; by 1927 more than 200 suspects were imprisoned under the act, including Subhas Chandra Bose. Its implementation curtailed a resurgence of nationalist violence in Bengal.[29] Branches of Jugantar formed in Chittagong and Dhaka, in present-day Bangladesh. The Chittagong branch found a strong leader in Surya Sen, and in December 1923 robbed the Chittagong office of the Assam-Bengal Railway. In January 1924 a young Bengali, Gopi Mohan Saha, shot dead a European he mistook for Calcutta police commissioner Charles Tegart. The assassin was praised by the Bengali press and, to Gandhi’s chagrin, proclaimed a martyr by the Bengal branch of the Congress. Around this time, Jugantar became closely associated with the Calcutta Corporation headed by Das and Subhas Chandra Bose and terrorists (and ex-terrorists) became factors in local Bengali government.

In 1923 another Anushilan-linked group, the Hindustan Republican Association, was founded in Benares by Sachindranath Sanyal and Jogesh Chandra Chatterjee. Influential in radicalising north India, it soon had branches from Calcutta to Lahore. A series of successful dacoities in Uttar Pradesh culminated in a train robbery in Kakori, and subsequent investigations and two trials broke the organization. Several years later, it was reborn as the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association.

In 1927, the Indian National Congress came out in favour of independence from Britain. Bengal had quietened over a four-year period, and the government released most of those interned under the Act of 1925 despite an unsuccessful attempt to forge a Jugantar-Anushilan alliance. Some younger radicals struck out in new directions, and many (young and old) took part in Congress activities such as the 1928 anti-Simon agitation. Congress leader Lala Lajpat Rai died of injuries received when police broke up a Lahore protest march in October, and Bhagat Singh and other members of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association avenged his death in December; Singh later bombed the legislative assembly. He and other HSRA members were arrested, and three went on a hunger strike in jail; Bengali bomb-maker Jatindra Nath Das persisted until his death in September 1929. The Calcutta Corporation passed a condolence resolution after his death, as did the Indian National Congress when Bhagat Singh was executed.

Final phase

As the Congress-led movement picked up its pace during the early 1930s, some former revolutionaries identified with the Gandhian political movement and became influential Congressmen (notably Surendra Mohan Ghose). Many Bengali Congressmen also maintained links with the Anushilan groups, and their revolutionary ideology and approach had not died away. In April 1930, Surya Sen and his associates raided the Chittagong Armoury. The Gandhi-led Salt March also saw the most active period of revolutionary terrorism in Bengal since World War I. In 1930 eleven British officials were killed, notably during the Writer’s Building raid of December 1930 by Benoy Basu, Dinesh Gupta and Badal Gupta. Three successive district magistrates in Midnapore were assassinated, and dozens of other actions were carried out during the first half of the decade. Although by 1931 a record 92 violent incidents were recorded, including the murders of the British magistrates of Tippera and Midnapore,[30] the terrorist movement in Bengal may be said to have ended in 1934.

A large portion of the Anushilan movement was attracted to left-wing politics during the 1930s, and those who did not join left-wing parties identified with Congress and the Congress Socialist Party. During the mass detentions of the 1930s surrounding the civil-disobedience movement, many members were won over to the Congress. Jugantar was formally dissolved in 1938; many former members continued to act together under Surendra Mohan Ghose, who was a liaison between other Congress politicians and Aurobindo Ghose in Pondicherry. During the late 1930s, Marxist-leaning members of the Anushilan in the CSP announced the formation of the Revolutionary Socialist Party.

Organisation

Structure

Anushilan and Jugantar each were organised on different lines, reflecting their divergence. Anushilan Samiti was centrally organised, with a rigid discipline and vertical hierarchy. Jugantar, was more loosely organised as an alliance of groups, acting under local leaders that occasionally coordinated their actions together. The prototype of Jugantar's organisation was Barin Ghosh's organisation set up in 1907, in the run-up to the Manicktolla conspiracy. It sought to emulate the model of Russian revolutionaries that was described by Frost. The regulations of the central Dhaka organization of the Anushilan Samiti were written down, and reproduced and summarised in government reports. According to one estimate, the Dacca Anushilan Samiti had at one point 500 branches, mostly in the eastern districts of Bengal, with 20,000 members. Branches were opened later in the western districts, Bihar, and the United Provinces. Shelters for absconders were established in Assam and in two farms in Tripura. Organisational documents shows a primary division between, on the one hand the two active leadersBarin Ghosh and Upendranath Bannerjee, and the rank-and-file on the other. Higher leaders including Aurobindo were supposed to be known only to the active leaders. Erstwhile members of Anushilan, particularly those of the Maniktala group, had suggested that the each group were interconnected with a vast web of secret societies throughout British India. However historian Peter Heehs concludes the links between provinces were limited to contacts between a few individuals like Aurobindo who was familiar with leaders and movements in Western India. He concludes the Maniktala society had links between the other groups and the Manicktalla society, such as the Anushilan and Atmannati Samitis, were more often competitive than co-operative. An internal circular of circa 1908 written by Pulin Behari Das, describes the division of the organisation in Bengal, which largely followed British administrative divisions, with central Samitis linked with a few small Samitis.

Cadre

At least initially, membership was predominantly Hindus, which was ascribed to the religious oath of initiation and was unacceptable to Muslims. Each member was assigned to one or more of three roles. These included collection of funds, implementation of planned actions and propaganda respectively. In practice, however, the fundamental division was between what was conceived as "military’’ work and ‘‘civil’’ work. Dals (teams) consisting of five or ten members led by a dalpati (teamleader) were grouped together in local samitis led by adhyakshas (executive officer) and other officers. These reported to district officers appointed by and responsible to the central Dhaka organization. This was commanded by Pulin Das and those who succeeded him during his periods of imprisonment. Samitis were divided into four functional groups: violence, organisation, keepers of arms, householder department. Communications were by special couriers and were written in secret code. This practice and many others were taken from literary sources and were in part a concession to the young men’s need to act out romantic drama. Less is known about the Jugantar network, which took the place of the Maniktala society after Alipore Bomb case. It faced divisions similar to Anushilan. Historian Leonard Gordon notes that at least in the period between 1910 and 1915, each group dal in the Jugantar network were separate units composed of a leader known as dada (lit: elder brother), and his followers. The dada was also guru, tutoring those under his command, practical skills, revolutionary ideology and strategy. Gordon suggests that the dada system developed out of pre-existing social structures in rural Bengal. Dadas both co-operated and competed with each other for men, money and material.

A large proportion of the cadre of the Samiti's component groups came from upper castes. By 1918, nearly ninety percent of the revolutionaries killed or convicted were from the Hindu castes of Brahmins, Kayasthas or Vaishyas.[27] As the Samiti spread its influence to other parts, particularly north India, it began to draw people of other religions and of varying religious commitments. For example, many who joined the Hindustan Republican Socialist Association were Marxists and many were militant atheists.[30] By the late 1930s, the membership had changed somewhat in the participation of members with more secular outlook. Wings of the Samiti also included prominent participation from women. Amongst the most famous of the latter were Pritilata Waddedar who led a Jugantor attack during the Chittagong Armoury raid, and Kalpana Dutta who manufactured bombs at Chittagong.[31]

Ideologies

Indian philosophies

The Samiti was influenced by the writings of the Bengalee nationalist author Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. The name of the organisation, Anushilan, itself is derived from Bankim's works espousing hardwork and spartan life. Bankim's cultural and martial nationalism exemplified in Anandamath, along with his interpretations of the Bhagavat Gita, are noted to be strong influences on the strain of nationalism that guided the early societies that merged into Anushilan Samiti.[32] To this was later added the philosophies and teachings of Swami Vivekananda. A search of the Dacca Anushilan Samiti library in 1908 showed that theGita was the most widely read book in the library. Among the "rules of membership" books by Vivekananda were strongly recommended for reading,[33] A recurring theme in these were emphasis on "Strong muscles and nerves of steel", which some historian identify as strongly influenced by Shakta Philosophy of Hinduism. The writings of the group's own leader Aurobindo Ghosh popularised Shakti, specifically the concept of Adya Shakti that is exemplified in his work Bhawani Mandir.[33] This marked the beginnings of interest in physical improvement and proto-national spirit among young Bengalees, and was driven by an effort to break away from the colonial stereotype of effeminacy imposed on the Bengalee. Physical fitness was symbolic of the recovery of masculinity, and part of a larger moral and spiritual training to cultivate control over the body, and develop national pride and a sense of social responsibility and service.[34][35] Peter Heehs, writing in 2010, notes the Samiti had three pillars in their ideologies: "cultural independence", "political independence", and "economic independence". In the latter, the Samiti differed from those engaging in the Swadeshi movement, which they decried solely as a "trader's movement".[36]

European influences

When the Samiti first came into prominence following the Muzaffarpur killings, its ideology was felt to be influenced by European anarchism. Lord Minto resisted the notion that its action may be the manifestation of political grievance by concluding that:

Murderous methods hitherto unknown in India ... have been imported from the West, ... which the imitative Bengali has childishly accepted.[37]

However others disagreed. John Morley was of the opinion that political violence exemplified by the Samiti were manifestations of Indian antagonism to the government, and was running a natural course which was culminating in assassinations.[37] Historians conclude that although there were influences of European nationalism and philosophies of liberalism.[38] In Bengal at large, through the decades 1860s and 1870s, there arose large numbers of akhras, or gymnasiums consciously designed along the lines of the Italian Carbonari which drew the youth.[39] These were influenced by the works of Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini and his Young Italy movement. Aurobindo himself studied the revolutionary nationalism of Ireland, France and America.[38] Hem Chandra Das, during his stay in Paris, is also noted to have interacted with European radical nationalists in the city,[38] returning to India an atheist and Marxist.[40]

Okakura and Nivedita

Among other notable personalities who are felt to have influenced the Samiti were the Japanese artist Kakuzo Okakura and Irish woman Margaret Noble, known widely as Sister Nivedita. Okakura was a proponent of Pan-Asianism. He visited Swami Vivekananda in Calcutta in 1902, and is noted to have inspired Pramathanath Mitra considerably in the early days of the Samiti.[38][41] However the extent of his involvement or influence is debated.[42] Nivedita was a disciple of Swami Vivekananda who moved from Ireland to live in Calcutta. She was noted to have contacts with Aurobindo, with Satish Bose and with Jugantar sub-editor Bhupendranath Bose. Nivedita is believed to have discussed and influenced people of the Samiti talking about their duties to motherland, and also providing the men of the Samiti with literature on revolutionary nationalism. She was at this time in correspondence with Peter Kropotkin, a noted anarchist.[38]

Later influences

A major section of the Anushilan movement had been attracted to Marxism during the 1930s, many of them studying Marxist–Leninist literature whilst serving long jail sentences. A minority section broke away from the Anushilan movement and joined the Communist Consolidation, and later the Communist Party of India (CPI). The majority of the Anushilan Marxists did however, whilst having adopted Marxist–Leninist thinking, feel hesitant over joining the Communist Party.[43] The Anushilanites distrusted the political lines formulated by the Communist International.They shared some critiques against the leadership of Joseph Stalin and the Comintern, but the Anushilan Marxists did not embrace Trotskyism.

Impact

Police reforms

The CIDs of Bengal and the provinces of Eastern Bengal and Assam came into existence with the birth of the revolutionary movement led by the Samiti.[7] By 1908, political crime duties took the services of one deputy Superintendent of Police, fifty-two Inspectors and Sub-Inspectors, and nearly seven hundred and twenty constables. Foreseeing a rise in the strength of the revolutionary movement, Sir Harold Stuart (then Secretary of State for India) implemented plans for a secret service to fight the menace posed by the Samiti.[44] A Political Crime branch of the C.I.D. (known as the "Special Department") was developed in September 1909, staffed by 23 officers and 45 men. The Government of India sanctioned Rs 2,227,000 for Bengal Police alone in the reforms of 1909-1910.[44] By 1908 a "Special Officer for Political Crime" was appointed from the Bengal Police under whom worked the Special Branch of Police. This post was first occupied by C.W.C. Plowden and later by F.C. Daly.[44] Godfrey Denham, then Assistant Superintendent of Police, served under the Special Officer for Political Crime.[44] Denham was credited with uncovering the Manicktolla safe house of the Samiti, raiding it in May 1908 which ultimately led to the Manicktolla conspiracy case. This case led to further expansion of the Special Branch in Bengal. The CID in Eastern Bengal and Assam (EBA) followed a similar course after being founded in 1906, with expansion from 1909 onwards. However, despite having funds available, EBA police's access to informers and secret agents remained difficult.[45] In EBA, a civil servant by the name of H.L. Salkeld uncovered the eastern branch of Anushilan Samiti, producing a four volume report and placing 68 suspects under surveillance.[12] However the Samiti evaded detailed intrusion by adopting the model of Russian revolutionaries, so much so that Police were unclear till 1909 if they were dealing with a single organisation or with a conglomeration of independent groups.[12] The visit of King George V to India in 1911 saw the introduction of measures to arm police better in Bengal and EBA. In 1912, the political branch of the Bengal CID was renamed Intelligence Branch, staffed with 50 officers and 127 men. The branch had separate sections dealing with explosives, assassinations and with Robberies.[19] The branch came to be headed by Charles Tegart, who built up network of agents and informers to infiltrate the Samiti.[19] Tegart would meet his agents under cover of darkness, at times disguising himself as Pathan or Kabuliwallah who were a common feature in the streets of Calcutta at the time.[19] Assisiting Denham and Petrie ably, Tegart led the investigation in the aftermath of the Dalhi-Lahore Conspiracy and identified Chandernagore as the main hub for the Samiti.[19] Tegart remained in Bengal police at least the 1930s, earning notoriety amongst the Samiti for his work, and was subjected to a number of assassination attempts. In 1924, Ernest Day, an Englishman, was shot dead by Gopinath Saha at Chowringhee Road in Calcutta, being mistaken for Tegart. In 1930, a bomb was thrown into Tegart's car at Dalhousie Square but Tegart managed to shoot the revolutionary and escaped unhurt. His efficient curbing of the revolutionary movement saw him earn praise from Lord Lytton and he was awarded the King's medal. In recognition of his efficiency, in 1937 Tegart was sent to the British Mandate of Palestine, then in the throes of the Arab Revolt. He advised the Inspector General on matters of security.[46]

Criminal Law Amendment 1908

In its fight against the Raj, the Samiti's members who turned approvers and the Bengal Police staff who were investigating the Samiti were consistently targeted. A number of assassinations were carried out of approvers who had turned crown-witnesses. In 1909 Naren Gossain, crown-witness for the prosecution in Alipore bomb case, was shot dead within Alipore Jail by Satyendranath Bose and Kanai Lal Dutt. Ashutosh Biswas, an advocate of Calcutta High Court in charge of prosecution of Gossain murder case, was shot dead within Calcutta High Court in 1909.In 1910, Shamsul Alam, Deputy Superintendent of Bengal Police responsible for investigating the Alipore Bomb case, was shot dead on the steps of Calcutta High Court. Failure of prosecution in violence linked to the Anushilan Samiti in a number of cases under the Criminal procedures act 1898 led to a special act whereby crimes of nationalist violence were to be tried by a special tribunal composed of three high-court judges. December 1908 saw the passage of the Criminal Law amendments under the terms of Regulation III of 1818 and to suppress associations formed for seditious conspiracies.[47] The act was first applied to deport nine Bengali revolutionaries to Mandalay prison in 1908. Despite these measures however, high standards of evidence demanded by the Calcutta High Court, insufficient investigations by police, and at times outright fabrication of evidence led to persistent failure to tame nationalist violence.[48] Police forces felt unable to deal with the operations of secretive nationalist organisations, leading to demands for special powers. These were opposed vehemently in the Indian press, which argued against any extension of already wide powers enjoyed by the police forces in India, and which it was argued was being used to oppress Indian people.[49]

Defence of India Act

The activities of the Samiti around the time of World War I, along with the threat of Ghadarite uprising in Punjab, led to the passage of the Defence of India Act in 1915. At the time of its enactment, act received universal support from Indian non-officiating members in the Governor General's council, from moderate leaders within Indian Political Movement. The British war effort had received popular support within India and the act received support on the understanding that the measures enacted were necessary in the war-situation. Its application saw a significant curtailment in revolutionary violence in India. However, the wide scope and widespread use amongst general population and against even moderate leaders led to growing revulsion within Indian population.

The enactment of the law saw 46 executions and 64 life sentences handed out to revolutionaries in Bengal and Punjab in the Lahore Conspiracy Trial and Benares Conspiracy Trial, and in tribunals in Bengal,[26] effectively crushing the revolutionary movement. The power of preventive detention were however applied more particularly to Bengal. By March 1916 widespread arrests helped Bengal Police crush the Dhaka Anushilan Samiti in Calcutta.[25] Regulation III and Defence of India Act was applied to Bengal from August 1916 on a wide scale. In Bengal Revolutionary violence in Bengal plummeted to 10 in 1917.[26] By the end of the war there were more than eight hundred interned in Bengal under the act. However, indiscriminate application of the act regardless of links to the revolutionary movement earned it increasing revulsion from within Indian populace.

Rowlatt act

With the impending lapse of the 1915 act in 1919, the Rowlatt Committee was appointed to recommend measures to deal with the threat from the revolutionary movement. Noting the success of preventing detention and deportation measures in curbing the Samiti, Rowlatt recommended an extension of the provisions of the Defence of India Act for a further three years with removal of habeas corpus provisions. The proposed Rowlatt acts were, however, met with universal opposition by the Indian members of the Viceroy's council, as well within the population in general, earning the title of "The Black Bills" from Mohandas Gandhi. Mohammed Ali Jinnah left the Viceroy's council in protest, after having warned the council of the dangerous consequences of enacting an extension of such an unpopular bill. Rowlatt's recommendations were enacted in the Rowlatt Bills. The agitations against the proposed Rowlatt bills took shape as the Rowlatt Satyagraha under the leadership of Gandhi, one of the first Civil disobedience movements that he would lead the Indian independence movement. The protests saw hartals in Delhi, public protests in Punjab as well as other protest movements across India. In Punjab, protests against the bills, along with a perceived threat of a Ghadrite uprising by the Punjab regional government culminated in the Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre in April 1919. After nearly three years of agitation, the government finally repealed the Rowlatt act and its component sister acts.

Bengal Criminal Law Amendment

Resurgence of radical nationalism linked to the Samiti after the 1922s led to the passage of the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Ordinance in 1924. This was enshrined as an act the following year. The act re-introduced extraordinary powers of detention to the police, and by 1927 more than 200 suspects had been imprisoned under the act, including Subhas Chandra Bose. The implementation of the act successfully curtailed a resurgence in nationalist violence in Bengal, at the time that the Hindustan Republican Association was rising in the United Provinces.[29]

Influence

Revolutionary nationalism

The nationalist publication Jugantar, which served as the organ of the Samiti, inspired fanatical loyalty among its readers and made a deep impression on this group.[50][51] By 1907 it was selling 7,000 copies which later rose to 20,000. Its message, aimed at elite politically conscious readers was essentially critique and defiance of British rule in India, and justification of political violence.[52] The publication inspired a proportion of the young men who joined Anushilan Samiti cited the influence of Jugantar in their decisions. The editor of the paper, Bhupendranath Datta was arrested and sentenced to one-year's rigorous imprisonment in 1907.[53] The Samiti responded with the attempt on the life of Douglas Kingsford who presided over the trial. Jugantar itself responded with defiant editorials.[53] The defiance of Jugantar saw it face five more prosecutions that left it in financial ruins by 1908. These prosecutions brought the paper more publicity, and helped disseminate the Samiti's ideology of revolutionary nationalism. Shukla Sanyal notes in 2014 that revolutionary terrorism as an ideology began to win support amongst a significant populace in Bengal, tacitly even if not overt.[51]

Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, the founder of the Hindu nationalist organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), learned from the Anushilan Samiti. He was sent to Calcutta by B. S. Moonje in 1910 to study medicine, and to learn techniques of violent nationalism from secret revolutionary organizations in Bengal.[54] There he lived with independence activist Shyam Sundar Chakravarthy,[55] and had contacts with revolutionaries like Ram Prasad Bismil.

Indian independence movement

James Popplewell, writing in 1995, noted that the Raj perceived the Samiti in its early days as a serious threat to its rule.[56] Its activities and ideologies found tacit support from within Bengali populace, even if not overt support. However historian Sumit Sarkar noted that the Samiti never mustered enough support to offer an urban rebellion or a guerrilla campaign. Both Peter Heehs and Sumit Sarkar noted that the Samiti called for complete independence a good twenty years before the Congress adopted this as its aim. A number of landmark events early in the Indian independence movement, including the revolutionary conspiracies of World War I, involved the Samiti intricately as noted in the Rowlatt report. In later years, the ascendant left-wing of the Congress, particularly Subhas Chandra Bose was suspected of having links with the Samiti. Heehs argued the actions of the revolutionary nationalists exemplified by the Samiti, forced the government to parley more seriously with the leaders of the legitimate movement. Gandhi was always aware of this. "At the Round Table Conference of 1931, the apostle of non-violence declared that he held 'no brief for the terrorists', but added that if the government refused to work with him, it would have the terrorists to deal with. The only way to 'say good-bye to terrorism' was 'to work the Congress for all it is worth'".[57]

Social influences

The founders of the Samiti were among the leading luminaries of Bengal at the time, who drove social changes far removed from the violent nationalist works that identified the Samiti in later years. The young men of Bengal were amongst the most active in the Swadeshi movement, and the participation of university students drew the ire of the Raj. R.W. Carlyle prohibited the participation of students in political meetings on the threat of withdrawal of funding and grants.[58] The decade preceding these decrees had seen Bengali intellectuals increasingly calling for indigenous schools and colleges to replace British institutions,[58] and sought to build indigenous institutions. Surendranath Tagore, of the Tagore family of Calcutta financed the establishment of Indian-owned banks and insurance companies. The 1906 Congress session in Calcutta established the National Council of Education as a nationalist agency to promote Indian institutions with their own independent curriculum designed to meet skills in technical and technological education that its founders felt necessary for building indigenous industries. With financial backing of Subodh Chandra Mallik, the Bengal National College (which later grew to be Jadavpur University) was established with Aurobindo as Principal.[58] Aurobindo participated in the Indian National Congress at the time. He used his platform in the Congress to present the Samiti as conglomeration of youth clubs, even as the Raj raised fears that it was a revolutionary nationalist organisation. It was during his time as Principal that Aurobindo started his nationalist publications Jugantar, Karmayogin and Bande Mataram.[58] The Student's mess at the College was frequented by students of East Benal who belonged to the Dhaka Anushilan Samiti, and was known to be hotbed of revolutionary nationalism, which was uncontrolled or even encouraged by the college.[59] Students of the college who later rose to prominence in the Indian revolutionary movement include M. N. Roy. The Samiti's ideologies further influenced patriotic nationalism. Sumit Sarkar notes that revolutionary terrorism resulted in "a wealth of patriotic songs" and "a new interest in regional and local history and folk traditions, the scientific works of J. C. Bose and P. C. Ray, and the Calcutta school of painting founded by Abanindranath Tagore".[40]

Communism in India

Through the 1920s and 1930s, many Anushilan members began identifying with Communism and leftist ideologies. Many of them studying Marxist–Leninist literature whilst serving long jail sentences. A minority section broke away from the Anushilan movement and joined the Communist Consolidation, and later the Communist Party of India. Former Jugantar leader Narendranath Bhattacharya, now known as M. N. Roy, became an influential member of the Communist International, helping to find the Communist Party of India. The majority of the Anushilanite Marxists, whilst having adopted Marxist–Leninist thinking, felt hesitant over joining the Communist Party.[43] Holding sharp differences with the CPI and Royist ideologies, the Anushilan marxists decided to join Congress Socialist Party (CSP), but keeping a separate identity within the party.[60] The RSP, which derived from the Samiti, held a strong influence in parts of Bengal. The psrty sent two parliamentarians in the 1952 Lok Sabha elections, both previously Samiti members. In 1969 RSP sympathizers in East Pakistan formed the Shramik Krishak Samajbadi Dal (SKSD). RSP and SKSD have maintained close ties since. The RSP is a minor partner in the Left Front which ruled the Indian state of West Bengal for 34 uninterrupted years. It also holds influence in South India, notably in parts of Kerala. The SUCI, another left wing party with a presence in Bengal, was founded in 1948 by Anushilan members.

In popular culture

The revolutionaries of the Samiti became household names in Bengal. Many of these educated and youthful men were widely admired and romanticised not only within Bengal but other parts of India too.[30] Ekbar biday de Ma ghure ashi (Bid me farewell, mother) is a 1908 song written by Bengali folkpoet Pitambar Das. Penned lamenting the execution of Kshudiram Bose, it could be heard in Bengal decades after Bose's death.[40] Today, the railway station were Bose was arrested is named Khudiram Bose Pusa Railway station in his honour. The 1926 nationalist novel Pather Dabi (Right of the way) by Bengali author Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay tells the story of a secret revolutionary nationalist organisation fighting the Raj. The protagost of the novel, Sabyasachi, is believed to have been modelled after Rash Behari Bose while the fictional organisation itself was thought to have been influenced by the Bengali revolutionary organisation. The novel was banned by The Raj as "Seditious", but acquired wild popularity. It formed the basis of a 1977 a Bengali language film, Sabyasachi, with Uttam Kumar playing the lead role of the protagonist. Do and Die is a historical account of the Chittagong armoury raid published in 2000. Penned by Indian author Manini chatterjee, it was awarded the Rabindra Puraskar, the highest literary award in Bengal. The book formed the basis of Khelein Hum Jee Jaan Sey (We Play with Our Lives), a 2010 Bollywood film retelling the story of the Chittagong armoury raid, with Abhishek Bachchan playing the role of Surya Sen.

A marble plaque marks the building in Calcutta where the first nucleus of the Samiti was founded. Many of the Samiti′ members are known in India and abroad, and are commemorated in different forms. Another plaque at the site of Barin Ghose's country house (in present day Ultadanga) marks the site were Ghosh and his group was arrested in the Alipore Bomb case. Many of the Samiti's members are known in India and abroad, and are commemorated in different forms. A number of Calcutta suburbs are today named after revolutionaries and nationalists of the Samiti. Grey Street, where Aurobindo Ghosh's press office stood, is today named Aurobido Sarani (Aurobindo avenue). Dalhousie square was renamed B.B.D Bag, named after Benoy, Badal, and Dinesh who raided the Writer's Building in 1926. Mononga lane, the site of Rodda & Co. heist, houses the busts of Anukul Mukherjee, Srish Chandra Mitra, Haridas Dutta, and Bipin Bihary Ganguly who participated in the heist. Chashakhand, a place 15 km east of Balasore where Jatindranath Mukherjee and his group made their last stand against Tegart's forces, honours the battlefield in Jatin's honour. The locality of Baghajatin in Kolkata is named after Jatin. In Bangladesh, the gallows where Surya Sen was executed are preserved as historical monument.

Citations

- ↑ Mitra 2006, p. 63

- ↑ Desai 2005, p. 30

- 1 2 Yadav 1992, p. 6

- ↑ Heehs 1992, p. 2

- 1 2 Sen 2010, p. 244 The militant nationalists thought of more direct and violent ways of ending British rule in India ... The chief apostle of militant nationalism in Bengal was Aurobindo Ghose. In 1902, there were three secret societies in Calcutta - Anushilan Samiti, founded by Pramatha Mitra, a barrister of the High Court of Calcutta; a society sponsored by Aurobindo Ghosh and a society started by Sarala Devi ... government found it difficult to suppress revolutionary activities in Bengal owing to ... leaders like Jatindranath Mukherjee, Rashbehari Bose and Jadugopal Mukheijee.

- ↑ Mohanta, Sambaru Chandra (2012). "Mitra, Pramathanath". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- 1 2 3 Popplewell 1995, p. 104

- ↑ Heehs 1992, p. 6

- ↑ Gupta 2006, p. 160

- ↑ Sanyal 2014, p. 30

- 1 2 3 Roy 1997, p. 5–6 The first such dacoity was committed by Naren ... Around this time, revolutionaries threw a bomb at the carriage of Mr and Mrs Kennedy ... in Muzaffarpur, under the mistaken notion that the 'notorious' Magistrate Kingsford was in the carriage. This led to the arrest of Kshudiram Bose and the discovery of the underground conspiratorial centre at Manicktala in eastern Calcutta ... Nandalal Banerjee, an officer in the Intelligence Branch of the Bengal Police was shot dead by Naren ... This was followed by the arrest of Aurobindo, Barin and others.

- 1 2 3 Popplewell 1995, p. 108

- 1 2 Roy 1997, p. 6 Aurobihdo's retirement from active politics after his acquittal ... Two centres were established, one was the Sramajibi Samabaya ... and the other in the name of S.D. Harry and Sons.

- ↑ Popplewell 1995, p. 111

- ↑ Roy 2006, p. 105

- ↑ M.N. Roy's Memoirs p3

- ↑ Roy 1997, p. 6–7 Shamsul Alam, an Intelligence officer who was then preparing to arrest all the revolutionaries ... was murdered by Biren Datta Gupta, one of Jatin Mukherjee's associates. This led to the arrests in the Howrah Conspiracy case.

- ↑ Popplewell 1995, p. 112

- 1 2 3 4 5 Popplewell 1995, p. 114

- ↑ Roy 1997, p. 7–8 The group foresaw the possibility of a world war and planned to launch a guerrilla war at that time, expecting assistance from Germany. ... Lala Hardayal, on his return to India in 1908, also became interested in the programme of the Bengal revolutionaries through Kissen Singh.

- ↑ Desai 2005, p. 320

- ↑ Popplewell 1995, p. 167

- ↑ Samanta 1995, p. 625

- ↑ Popplewell 1995, p. 201

- 1 2 3 Popplewell 1995, p. 210

- 1 2 3 Bates 2007, p. 118

- 1 2 Sarkar 2014, p. 107 In a 1918 official list of 186 killed or convicted revolutionaries, no less than 165 came from the three upper castes, Brahman, Kayastha, and Vaidya.

- ↑ Morton 2013, p. 80 "Following ... the first two decades of the twentieth century, the Indian government's law enforcement officials had claimed that the detention of alleged Bengali terrorists was a success, a claim that served to justify the Rowlatt Report's recommendation of emergency measures in 1918. In response to this, many leaders of the revolutionary movement went underground in the 1920s and fled Bengal to other British territories, particularly Burma."

- 1 2 Heehs 2010, pp. 171–172 "The activity and influence of the Bengal terrorists led to the passage in 1924 of the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Ordinance, extended the next year as an Act. This again gave the police extraordinary powers, and between 1924 and 1927 almost 200 suspects were imprisoned, among them Subhas Bose. Acts of terrorism in Bengal dropped off; but an Anushilan-linked group in the United Provinces [the Hindustan Republican Association] grew to some importance."

- 1 2 3 Chowdhry 2000, p. 138

- ↑ "Bollywood & Revolutionary Bengal: Revisiting the Chittagong Uprising (1930-34)". History Workshop.

- ↑ Ray 1988, p. 83

- 1 2 Ray 1988, p. 84

- ↑ Bandyopadhyaya 2004, p. 260 The physical culture movement became a craze ... this was a psychological attempt to break away from the colonial stereotype of effeminacy imposed on the Bengalees. Their symbolic recovery of masculinity ... remained parts of a larger moral and spiritual training to achieve mastery over body, develop a national pride and a sense of social service.

- ↑ Heehs 1992, p. 3

- ↑ Heehs 2010, p. 161 "The ideology of revolutionary publicists such as Bipin Chandra Pal and Aurobindo Ghose ... had three major components: political independence or swaraj; economic independence as promoted by the swadeshi-boycott movement; and the drive for cultural independence by means of national education ... A circular of the Anushilan Samiti states: "This Samiti has no open relationship with any kind of popular and outward Swadeshi, that is (the boycott of) belati [foreign] articles ... To be mixed up in ... such affairs is entirely against the principles of the Samiti" (Ghosh 1984: 94). Members of Barin Ghose's group likewise stigmatized the swadeshi-boycott movement as bania (shopkeeper) politics."

- 1 2 Heehs 2010, p. 160, paras 1–2 "[Morley] wrote to Viceroy Lord Minto, 'that Indian antagonism to Government would run slowly into the usual grooves, including assassination' ... he considered Bengali terrorism to be an almost natural result of political discontent. Minto, on the other hand, considered it entirely imitative. Writing to Morley after the Muzaffarpur attempt, Minto declared that the conspirators aimed 'at the furtherance of murderous methods hiterto unknown in India which have been imported from the West, and which the imitative Bengali has childishly accepted' ... the terrorists were playing at being 'anarchists.'"

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heehs 2010, p. 160 para 3 "There were ... some foreign influences on Bengali Terrorism ... Aurobindo Ghose's study of the revolutionary movements of Ireland, France, and America. Members of the early 'secret societies' drew some of their inspiration from Mazzini ... The Japanese critic Kakuzo Okakura inspired Pramathanath Mitra and others with revolutionary and pan-Asiatic ideas just when the samiti movement was getting started. The Irishwoman Margaret Noble, known as Sister Nivedita after she became a disciple of Swami Vivekananda, had some contact with Aurobindo Ghose and with younger men like Satish Bose and Jugantar sub-editor Bhupendranath Bose. Nivedita was in correspondence with the non-terroristic anarchist Peter Kropotkin, and she is known to have had revoutionary beliefs. She gave the young men a collection of books that included titles on revolutionary history and spoke to them about their duty to the motherland ... undoubted connection of Hem Chandra Das with European revolutionaries in Paris in 1907."

- ↑ Heehs 1994, p. 534 "[Around 1881] a number of self-styled 'secret societies' were set up in Calcutta that were consciously modelled on the Carbonari and Mazzini's Young Italy Society ... They were in fact simply undergraduate clubs, long on nebulous ideals but short on action."

- 1 2 3 Sarkar 2014, p. 106 Hemchandra Kanungo, to cite the earliest example, came back from Paris as an atheist with some interest in Marxism ... a street-beggar's lament for Kshudiram, for instance, could still be heard in Bengal decades after his execution.

- ↑ Samanta 1995, p. 257

- ↑ Heehs 1993, p. 260

- 1 2 Saha, Murari Mohan (ed.), Documents of the Revolutionary Socialist Party: Volume One 1938–1947. Agartala: Lokayata Chetana Bikash Society, 2001. pp. 20–21

- 1 2 3 4 Popplewell 1995, p. 105

- ↑ Popplewell 1995, pp. 105–107

- ↑ "Londonderry born imperial policeman remembered". Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ↑ Riddick 2006, p. 93

- ↑ Horniman 1984, p. 42 [There are] records of cases during the years from 1908 to 1914 which were abortive ... due to the usual faults of police work in India—the hankering~after approvers and confessions, to be obtained by any means, good or bad; the concoction of a little evidence to make a bad case good- or a good case better; and the suppression of facts which fail to fit the theory.

- ↑ Horniman 1984, p. 43 Police authorities took up the attitude that ... they were helpless in the face of a secret organisation ... Demands were put forward for special powers, the lowering of the standard of evidence, and other devices for the easy success of the police ... the whole Indian Press anticipated with the liveliest apprehension the prospect of any extension of those wide powers which already enabled the police to oppress the people.

- ↑ Sanyal 2014, p. 89 "The Jugantar newspaper served as the propaganda vehicle for a loose congregation of revolutionaries led by individuals like Jain Banerjee and Barin Ghose who drew inspiration from ... Aurobindo Ghose."

- 1 2 Sanyal 2014, p. 93 "This attitude cost the paper dearly. It suffered five more prosecutions that, by July 1908, brought about its financial ruin … The trials brought the paper a great deal of publicity and helped greatly in the dissemination of the revolutionary ideology ... testimony to the fanatical loyalty that the paper inspired in its readers and the deep impression that the Jugantar writings made on them ... revolutionary terrorism as an ideology began to win if not overt, then at least the tacit, support of Bengalis."

- ↑ Sanyal 2014, pp. 90–91 "[Sanyal translates from Jugantar:] "In a country where the ruling power relies on brute force to oppress its subjects, it is impossible to bring about Revolution or a change in rulers through moral strength. In such a situation, subjects too must rely on brute force." ... The Jugantar challenged the legitimacy of British rule ... [its] position thus amounted to a fundamental critique of the British government ... By 1907 the paper was selling 7000 copies, a figure that went up to 20,000 soon after. The Jugantar ideology was basically addressed to an elite audience that was young, literate and politically radicalized."

- 1 2 Sanyal 2014, pp. 91–92 "Bhupendranath Dutt, the editor and proprietor of the Jugantar was arrested in July 1907 and charged under section 124 A ... Bhupendranath was sentenced to a year's rigorous imprisonment ... The Jugantar's stance was typically defiant ... The paper did nothing to tone down the rhetoric in its future editions."

- ↑ Jaffrelot 1996, p. 33

- ↑ M. L. Verma Swadhinta Sangram Ke Krantikari Sahitya Ka Itihas (Part-2) p.466

- ↑ Popplewell 1995, p. 109

- ↑ Heehs 2010, p. 174

- 1 2 3 4 Heehs 2008, p. 93

- ↑ Samanta 1995, p. 303

- ↑ Saha, Murari Mohan (ed.), Documents of the Revolutionary Socialist Party: Volume One 1938–1947. Agartala: Lokayata Chetana Bikash Society, 2001. p. 35-37

References

- Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (2003), Banglapedia, the national encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka .

- Bandyopadhyaya, Sekhar (2004), From Plassey to Partition: A History of modern India, Orient Longman, ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2 .

- Bates, Crispin (2007), Subalterns and Raj: South Asia since 1600, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-21483-4 .

- Chakrabarti, Panchanan (1995), Revolt .

- Chowdhry, Prem (2000), Colonial India and the Making of Empire Cinema: Image, Ideology and Identity, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-5792-2 .

- Desai, A. R. (2005), Social Background of Indian Nationalism, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-8171546671 .

- Ganguli, Pratul Chandra (1976), Biplabi'r jibandarshan .

- Guha, Arun Chandra, Aurobindo and Jugantar .

- Heehs, Peter (1993), The Bomb in Bengal: The Rise of Revolutionary Terrorism in India, 1900–1910, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563350-4 .

- Heehs, Peter (July 1994), "Foreign Influences on Bengali Revolutionary Terrorism 1902-1908", Modern Asian Studies, 28 (3): 533–536, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00011859, ISSN 0026-749X .

- Heehs, Peter (1992), History of Bangladesh 1704-1971 (Vol I), Dhaka: Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-9845123372 .

- Heehs, Peter (2008), The Lives of Sri Aurobindo, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14098-0 .

- Heehs, Peter (2010), "Revolutionary Terrorism in British Bengal", in Boehmer, Elleke; Morton, Stephen, Terror and the Postcolonial, Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9154-8 .

- Horniman, B. G. (1984), British Administration & The Amritsar Massacre, Delhi: Mittal Publications, OCLC 12553945 .

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (1996), The Hindu Nationalist Movement in India, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-10334-4 .

- Morton, Stephen (2013), States of Emergency: Colonialism, Literature and Law, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 978-1-84631-849-8 .

- Mukherjee, Jadugopal (1982), Biplabi jibaner smriti (2nd ed.) .

- Mitra, Subrata K. (2006), The Puzzle of India's Governance: Culture, Context and Comparative Theory, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-34861-4 .

- Popplewell, Richard James (1995), Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of the Indian Empire, 1904-1924, London: Frank Cass, ISBN 978-0-7146-4580-3 .

- Ray, Rajat Kanta (1988), "Moderates, Extremists, and Revolutionaries: Bengal, 1900-1908", in Sisson, Richard; Wolpert, Stanley, Congress and Indian Nationalism, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06041-8 .

- Riddick, John F. (2006), The History of British India: A Chronology, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-32280-8 .

- Roy, Samaren (1997), M. N. Roy: A Political Biography, Orient Longman, ISBN 81-250-0299-5 .

- Roy, Shantimoy (2006), "India Freedom Struggle and Muslims", in Engineer, Asghar Ali, They Too Fought for India's Freedom: The Role of Minorities, Sources of History, Vol. III, Hope India Publications, p. 105, ISBN 9788178710914 .

- Samanta, A. K. (1995), Terrorism in Bengal, Vol. II, Government of West Bengal .

- Sanyal, Shukla (2014), Revolutionary Pamphlets, Propaganda and Political Culture in Colonial Bengal, Delhi: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-06546-8 .

- Sarkar, Sumit (2014) [First published 1983], Modern India 1886-1947, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-4085-9 .

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (2010), An Advanced History of Modern India, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0230-32885-3 .

- Yadav (1992), Missing or empty

|title=(help) . - Majumdar, Purnima (2005), Sri Aurobindo, Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd, ISBN 978-8128801945 .

- Radhan, O.P. (2002), Encyclopaedia of Political Parties, New Delhi: Anmol Publications PVT. LTD, ISBN 9788174888655 .