Bengali Muslims

| বাঙালি মুসলমান (Bangali Musolman) | |

|---|---|

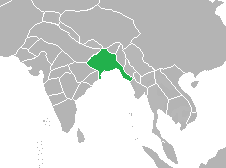

Muslim-majority districts of Bengal highlighted in green on a map in 1909 | |

| Total population | |

| 185 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 146,000,000 (2011)[1] | |

| 36,400,000 (2011)[2] | |

| 2,200,000 (2011)[3] | |

| 1,200,000 (2010)[4] | |

| 700,000 (2013)[5] | |

| 500,000 (2009)[6] | |

| 377,126 (2011)[7] | |

| 230,000 (2008)[8] | |

| 200,000 (2010)[9] | |

| 150,000 (2014)[10] | |

| 143,619 (2007) | |

| 115,746 (2013)[11] | |

| Languages | |

| Bengali | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

|

Bengali homeland |

|

Bengali Muslims (Bengali: বাঙালি মুসলমান)[12][13] are an ethnic, linguistic, and religious population who make up the majority of Bangladesh's citizens and the largest minority in the Indian states of West Bengal and Assam.[14] They are Bengalis who adhere to Islam and speak the Bengali language, which is written with the Eastern Nagari alphabet. They form the largest Bengali and the second largest Muslim ethnic group in the world (after Arab Muslims).[15]

Bengal was a leading power of the medieval Islamic East.[16] The endogamous Bengali Muslim population emerged as a synthesis of Islamic and Bengali cultures. After the Partition of India in 1947, they comprised the demographic majority of Pakistan until the independence of East Pakistan (historic East Bengal) as Bangladesh in 1971.

Identity

A Bengali is a person of ethnic and linguistic heritage from the Bengal region in South Asia speaking the Indo-Aryan Bengali language. Islam arrived in the first millennium and influenced the native Bengali culture. The influx of Persian, Turkic, Arab and Mughal settlers contributed further diversity to the cultural development of the region.[17] However, historians including Richard Maxwell Eaton, Ahmed Sharif, Muhammad Mohar Ali and Jadunath Sarkar are in agreement that the bulk of Muslims are descended from Buddhists who were converted to Islam by missionaries.[17][18][19] Today, most Bengali Muslims live in the modern state of Bangladesh, the world's third largest Muslim-majority country, along with the Indian states of West Bengal and Assam.[14]

The dominant majority of Bengali Muslims are Sunnis who follow the Hanafi school of jurisprudence. There are also minorities of Shias and Ahmadiyas, as well as people who identify as non-denominational (or "just a Muslim").[20]

History

Pre-Islamic history

Rice-cultivating communities existed in Bengal since the second millennium BCE. The region was home to a large agriculturalist population influenced by Indian religions, but was not fully integrated into the caste system.[21] Buddhism influenced the region in the first millennium. The Bengali language developed from Apabhramsa and Magadhi Prakrit between the 7th and 10th centuries. It once formed a single Indo-Aryan branch with Assamese and Oriya, before the languages became distinct.[22]

Early explorers

Early Muslim traders and merchants visited Bengal while traversing the Silk Road in the first millennium. One of the earliest mosques in South Asia is under excavation in northern Bangladesh, indicating the presence of Muslims in the area around the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad.[23] Starting in the 9th century, Muslim merchants increased trade with Bengali seaports.[24] Coins of the Abbasid Caliphate have been discovered in many parts of the region.[25]

Early Islamic kingdoms

.jpg)

The Muslim conquest of the Indian subcontinent took place between the 12th and 16th centuries. Bengal became a province of the Delhi Sultanate in 1204. In the 14th century the Sultanate of Bengal became independent and emerged as a regional power.[26] It adopted Bengali as one of its official languages, alongside Persian, the diplomatic language of the Islamic world, and Arabic, the liturgical language of the religion. The Sultanate also ruled parts of Arakan and Assam. The Sur Empire briefly overtook the region in the 16th century. During the sultanate period, Hindu aristocrats occupied prominent positions in the administration.[19]

The Mughal Empire eventually controlled the region under its Bengal Subah viceregal province. The Mughal Emperors considered Bengal their most prized province. Emperor Akbar redeveloped the Bengali calendar.[27] Emperor Aurangazeb called Bengal the Paradise of Nations.[28] Two Bengal viceroys – Muhammad Azam Shah and Azim-us-Shan – assumed the imperial throne. Mughal Bengal became increasingly independent under the Nawabs of Bengal in the 18th century.[29]

Islamization

The agrarian reforms of the Mughal Empire also played a crucial role in developing Bengali Muslim society. According to historian Richard M. Eaton, Islam became the religion of the plough in the Bengal delta.[16] The delta was the most fertile region in the empire. Mughal development projects cleared forests and established thousands of Sufi-led villages, which became industrious farming and craftsmanship communities.[30] The projects were most evident in the Bhati region of East Bengal, the most fertile part of the delta.[31]

People from various parts of the Muslim world settled in the region. Settlers intermarried with the local population.[16] This made East Bengal a thriving melting pot with strong trade and cultural networks. It was the most prosperous part of the subcontinent.[30][32] East Bengal became the center of the Muslim population in the eastern subcontinent and corresponds to modern-day Bangladesh.[31]

British period

The region fell to the control of the British Empire in 1757.

British-ruled Bengal was a hotbed of anti-colonial rebellion. In the early 19th century, Titumir led a peasant uprising against colonial rule. Haji Shariatullah led the Faraizi movement, advocating Islamic revivalism.[33] The Faraizis sought to create a caliphate and cleanse the region's Muslim society of what they deemed "un-Islamic practices". They were successful in galvanizing the Bengali peasantry against colonial authorities. However, the movement suffered crackdowns after the Mutiny of 1857[34] and lost impetus after the death of Haji Shariatullah's son Dudu Miyan.[33]

After 1870, Muslims began seeking English education increasingly. Under the leadership of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan the promotion the English language among Muslims of India also influenced Bengali Muslim society.[19] Social and cultural leaders among Bengali Muslims during this period included Munshi Mohammad Meherullah, who countered Christian missionaries,[35] writers Ismail Hossain Siraji and Mir Mosharraf Hossain; and feminists Nawab Faizunnesa and Roquia Sakhawat Hussain.

The creation of Eastern Bengal and Assam established visions for a sovereign Muslim-majority homeland in the eastern subcontinent. Low income Muslims after passing matriculation, looked for jobs as clerks, peons and orderlies but Hindu babus refused to employ them.[19] So, instigated by the British, upper class Muslims formed the Muslim League in Dhaka in 1906.[19] The early Muslim League dominated politics in East Bengal. A. K. Fazlul Huq was the first Prime Minister of Bengal under British rule. Bengali Muslims also dominated politics in Colonial Assam, where Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani emerged as a populist leader. Muhammed Saadulah served as the first Prime Minister of Assam.

1947 Partition and Bangladesh

An important moment in the history of Bengali self-determination was the Lahore Resolution in 1940, which was promoted by British Bengal premier A. K. Fazlul Huq. The resolution initially called for the creation of a sovereign state in the "Eastern Zone" of British India.[36] However, its text was later changed by the top leadership of the Muslim League. Despite calls from liberal Bengali Muslim League leaders for an independent United Bengal, the British moved forward with the Partition of Bengal and India in 1947. The Radcliffe Line made East Bengal a part of the Dominion of Pakistan. It was later renamed as East Pakistan, with Dhaka as its capital. The All Pakistan Awami Muslim League was formed in Dhaka in 1949.[37] The organization's name was later secularized as the Awami League in 1955.[38] The party was supported by the Bengali bourgeois, agriculturalists, the middle class, and the intelligentsia.[39] Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin, Mohammad Ali of Bogra, and H. S. Suhrawardy each served as Pakistan's prime minister during the 1950s; however, all three were deposed by the military-industrial complex in West Pakistan. The Bengali Language Movement in 1952 received strong support from Islamic groups, including the Tamaddun Majlish. Bengali nationalism increased in East Pakistan during the 1960s, particularly with the Six point movement for autonomy. The rise of pro-democracy and pro-independence movements in East Pakistan, with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the principal leader, led to the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971.

Bangladesh was founded as a secular nation. In 1977, however, President Ziaur Rahman, trying to consolidate his power under martial law, removed secularism from the constitution and replaced it with "a commitment to the values of Islam."[40] In 2010, the Bangladesh Supreme Court reaffirmed secular principles in the constitution.[41]

Science and technology

The Bengali numerals are derived from ancient Indian mathematics, which also influenced the development of Arabic numerals and science in the medieval Islamic world.

Historical Islamic kingdoms that existed in Bengal employed several clever technologies in numerous areas such as architecture, agriculture, civil engineering, water management, etc. The creation of canals and resoirvoirs was a common practice for the sultanate. New methods of irrigation were pioneered by the Sufis. Bengali mosque architecture featured terracotta, stone, wood and bamboo, with curved roofs, corner towers and multiple domes. During the Bengal Sultanate, a distinct regional style flourished which featured no minarets, but had richly designed mihrabs and minbars as niches.

Islamic Bengal had a long history of textile weaving ] including export of muslin during the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, the weaving of Jamdani is classified by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage.

Modern science was begun in Bengal under British colonial rule. Railways were introduced in 1862, making Bengal one of the earliest regions in the world to have a rail network. For the general population, opportunities for formal science education remained limited. The colonial government and the Bengali elite established several institutes for science education. The Nawabs of Dhaka established Ahsanullah School of Engineering which later became the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Bengali Muslim American Fazlur Rahman Khan became one of the most important structural engineers in the world, helping design the world's tallest buildings. Another Bengali Muslim American, Jawed Karim, was the co-founder of YouTube.

In 2016, the modernist Bait-ur-Rouf Mosque, inspired by the Bengal Sultanate-style of buildings, won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

Demographics

Bengali Muslims constitute the world's second-largest Muslim ethnicity (after the Arab world) and the largest Muslim community in South Asia.[42] An estimated 146 million Bengali Muslims live in Bangladesh, where Islam is the state religion and commands the demographic majority.[43] The Indian state of West Bengal is home to an estimated 24.6 million Bengali Muslims. Two districts in West Bengal – Murshidabad and Maldah have a Muslim majority and North Dinajpur has a plurarity.[44] The Indian state of Assam has over 11 million Bengali Muslims. Nine of out thirty-seven districts in Assam have a Muslim majority. The Rohingya community in western Myanmar have significant Bengali Muslim heritage.[45]

A large Bengali Muslim diaspora is found in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, which are home to several million expatriate workers from South Asia. A more well-established diaspora also resides in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Pakistan. The first Bengali Muslim settlers in the United States were ship jumpers who settled in Harlem, New York and Baltimore, Maryland in the 1920s and 1930s.[46]

Culture

Surnames

Surnames in Bengali Muslim society reflect the region's cosmopolitan history. They are mainly of Arabic and Persian origin, with a minority of secular Bengali surnames.

Art

Sheikh Zainuddin was a prominent Bengali Muslim artist in the 18th century during the colonial period. His works were inspired by the style of Mughal courts.[47]

Architecture

Architecture is considered the supreme form of Islamic art. An indigenous style of Islamic architecture flourished in Bengal during the medieval Sultanate period.[48] Terracotta and stone mosques with multiple domes proliferated in the region. Bengali Muslim architecture emerged as a synthesis of Bengali, Persian, Byzantine, and Mughal elements.

The Indo-Saracenic style influenced Islamic architecture in South Asia during the British Raj. A notable example of this period is Curzon Hall. Modern and contemporary Islamic architecture evolved in the region since the 1950s.

Sufism

Sufi spiritual traditions are central to the Bengali Muslim way of life. The most common Sufi ritual is the Dhikr, the practice of repeating the names of God after prayers. Sufi teachings regard the Prophet Muhammad as the primary perfect man who exemplifies the morality of God.[49] Sufism is regarded as the individual internalization and intensification of the Islamic faith and practice. The Sufis played a vital role in developing Bengali Muslim society during the medieval period. Historic Sufi missionaries are regarded as saints, including Shah Jalal, Khan Jahan Ali, Shah Farhan, Shah Amanat, and Khwaja Enayetpuri. Their mausoleums are focal points for charity, religious congregations, and festivities.

The Qadiri, Maizbhandaria, Naqshbandi, Chishti, Mujaddid, Ahmadi, Mohammadi, Soharwardi and Rifai orders are among the most widespread Sufi orders in the region.[50]

Syncretism

As part of the conversion process, a syncretic version of mystical Sufi Islam was historically prevalent in medieval and early modern Bengal. The Islamic concept of tawhid was diluted into the veneration of Hindu folk deities, who were now regarded as pirs.[51] Folk deities such as Shitala (goddess of smallpox) and Oladevi (goddess of cholera) were worshipped as pirs among certain sections of Muslim society.[17]

Language

Bengali Muslims maintain their indigenous language and script.[52] This tradition is similar to that of Central Asian and Chinese Muslims.

Bengali evolved as the most easterly branch of the Indo-European languages. The Bengal Sultanate promoted the literary development of Bengali over Sanskrit, apparently to solidify their political legitimacy among the local populace. Bengali was the primary vernacular language of the Sultanate.[53] Bengali borrowed a considerable amount of vocabulary from Arabic and Persian. Under the Mughal Empire, considerable autonomy was enjoyed in the Bengali literary sphere.[54][55] The Bengali Language Movement of 1952 was a key part of East Pakistan's nationalist movement. It is commemorated annually by UNESCO as International Mother Language Day on 21 February.

Literature

While proto-Bengali emerged during the pre-Islamic period, the Bengali literary tradition crystallized during the Islamic period. As Persian and Arabic were prestige languages, they significantly influenced vernacular Bengali literature. The first efforts to popularize Bengali among Muslim writers was by the Sufi poet Nur Qutb Alam.[56][57] The poet established the Rikhta tradition which saw poems written in half Persian and half colloquial Bengali. The invocation tradition saw Bengali Muslim poets re-adapting Indian epics by replacing invocations of Hindu gods and goddesses with figures of Islam. The romantic tradition was pioneered by Shah Muhammad Sagir, whose work on Yusuf and Zulaikha was widely popular among the people of Bengal.[58] Other notable romantic works included Layla Madjunn by Bahram Khan and Hanifa Kayrapari by Sabirid Khan.[56] The Dobashi tradition features the use of Arabic and Persian vocabulary in Bengali texts to illustrate Muslim contexts.[56] Medieval Bengali Muslim writers produced epic poetry and elegies, such as Rasul Vijay of Shah Barid, Nabibangsha of Syed Sultan, Janganama of Abdul Hakim and Maktul Hussain of Mohammad Khan. Cosmology was a popular subject among Sufi writers.[59] In the 17th century, Bengali Muslim writers such as such as Alaol found refuge in Arakan where he produced his epic, Padmavati.[58]

Bengal was also a major center of Persian literature. Several newspapers and thousands of books, documents and manuscripts were published in Persian for 600 years. The Persian poet Hafez dedicated an ode to the literature of Bengal while corresponding with Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah.[60]

The first Bengali Muslim novelist was Mir Mosharraf Hossain in the 19th century. The highly acclaimed poetry of Kazi Nazrul Islam espoused spiritual rebellion against fascism and oppression. Nazrul also wrote Bengali ghazals. Begum Rokeya was a pioneering Bengali female writer who published Sultana's Dream, one of the earliest examples of feminist science fiction. The Muslim Literary Society of Bengal was founded by free-thinking and progressive teachers of Dacca University under the chairmanship of Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah on 19 January 1926. The Freedom of Intellect Movement was championed by the society.[61] When Bengal was partitioned in 1947, a distinct literary culture evolved in East Pakistan and modern Bangladesh. Shamsur Rahman was regarded as the country's poet laureate. Jasimuddin became noted for poems and songs reflecting life in rural Bengal. Humayun Ahmed promoted the Bangladeshi field of magical realism. Akhtaruzzaman Elias was noted for his works set in Old Dhaka. Tahmima Anam has been a noted writer of Bangladeshi English literature.

Literary societies

- Kendriyo Muslim Sahitya Sangsad[62]

- Muslim Sahitya-Samaj[63]

- Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Samiti[64]

- Bangiya Sahitya Bisayini Mussalman Samiti[65]

- Mohammedan Literary Society[66]

- Purba Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad[67]

- Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad, 1952[68]

- Uttar Banga Sahitya Sammilani[69]

- Rangapur Sahitya Parisad[70]

Literary magazines

- Mussalman Sahitya Patrika[71]

- Saogat

- Begum (magazine)

Music

A notable feature of Bengali Muslim music is the syncretic Baul tradition. The most famous practitioner was Fakir Lalon Shah. Baul music is included in the UNESCO Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Nazrul Sangeet is the collection of 4,000 songs and ghazals written by Kazi Nazrul Islam.

South Asian classical music is widely prevalent in the region. Alauddin Khan, Ali Akbar Khan, and Gul Mohammad Khan were notable Bengali Muslim exponents of classical music.

In the field of modern music Runa Laila became widely acclaimed for her musical talents across South Asia.

Cuisine

Dhaka the capital of Mughal Bengal and present day capital of Bangladesh has been the epidome of Persio-Bengali and Arabo-Bengali cuisines a contrast to Calcutta the former capital of the British India and capital of present-day West Bengal which was the central point of Anglo-Indian cuisine. Within Bengali cuisine, Muslim dishes include the serving of meat curries, pulao rice, various biryani preparations, and dry and dairy-based desserts alongside traditional fish and vegetables. Bakarkhani breads from Dhaka were once immensely popular in the imperial court of the Mughal Empire. Other major breads consumed today include naan and paratha. In present-day Bangladesh the Mughal-influenced foods are immensely popular such as Shuti Kabab, Kalo Bhuna, Korma, Rôst, Mughlai Porota, Jali Kabab, Shami Kabab, Akhni, Tehari, Tanduri Chicken, Kofta, Phirni and Shingara. Different types of Bengali biryani include the Kachi (mutton), Illish pulao (hilsa), Tehari (beef), and Murg Pulao (chicken). Mezban is a renowned spicy beef curry from Chittagong. Halwa, pithas, yogurt, and shemai are typical Muslim desserts in Bengali cuisine.

Festivals

Eid-ul-Fitr at the end of Ramadan is the largest religious festival of Bengali Muslims. The festival of sacrifice takes place during Eid-al-Adha, with cows and goats as the main sacrificial animals. Muharram and the Prophet's Birthday are national holidays in Bangladesh. Other festivals like Shab-e-Barat feature prayers and exchange of desserts.

Secular festivals are based on the Bengali calendar which was redesigned by the Mughal Emperor Akbar. Celebrated by Bengalis of all faiths, they include the Bengali New Year, Spring Festival, and Autumn Harvest Festival.

Bishwa Ijtema

The Bishwa Ijtema, organized annually in Bangladesh, is the second-largest Islamic congregation after the Hajj. It was founded by the orthodox Sunni Tablighi Jamaat movement in 1954.

Leadership

There is no single governing body for the Bengali Muslim community, nor a single authority with responsibility for religious doctrine. However, the semi-autonomous Islamic Foundation, a government institution, plays an important role in Islamic affairs in Bangladesh, including setting festival dates and matters related to zakat. The general Bengali Muslim clergy remains deeply orthodox and conservative. Members of the clergy include Mawlānās, Imams, Ulamas, and Muftis.

The clergy of the Bengali Muslim Shia minority have been based in the old quarter of Dhaka since the 18th century.

Notable individuals

Muhammad Yunus is the first Bengali Muslim Nobel laureate. Begum Rokeya was one of the world's first Muslim feminists. Kazi Nazrul Islam was renowned as the Rebel Poet of British India and the creator of the national march of Bangladesh. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was the first President of Bangladesh. Iskander Mirza was the first president of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Khwaja Salimullah was one of the founders of the All-India Muslim League. Rushanara Ali was the amongst the first Muslim MPs in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. Fazlur Rahman Khan was an American Bengali Muslim engineer who reshaped modern skyscraper construction. Jawed Karim is one of the co-founders of Youtube. Salman Khan is a co-founder of Khan Academy. Humayun Rashid Choudhury served as President of the United Nations General Assembly. M. A. G. Osmani was a four star general who founded the Bangladesh Armed Forces. Altamas Kabir was the first Bengali Muslim Chief Justice of India.[72] Irrfan Khan and Nafisa Ali are prominent Bengali Muslims who act in Indian cinema. Alaol was a medieval Bengali Muslim poet who worked in the royal court of Arakan.[58] Mohammad Ali Bogra served as the Prime Minister of Pakistan. Begum Sufia Kamal was a leading Bengali Muslim feminist, poet, and civil society leader. Zainul Abedin was the pioneer of modern Bangladeshi art. Muzharul Islam was the grand master of South Asian modernist terracotta architecture.

Human rights issues

In recent years, the Indian Bengali Muslim community has faced increased Islamophobic attacks, although prejudice against the Bengali Muslims stemmed in 1946.[14] In Assam, they are seen as "illegal Bangladeshis" regularly abused and called by the racial epithet "miya."[14] In the 1983 Nellie massacre, over 2000 Bengali Muslims were killed in just six hours.[14] During the 2012 Assam violence saw widespread attacks on the state's centuries-old Bengali Muslim population. Indian Hindu nationalist politicians have accused Bangladesh of trying to expand its territory by ostensibly promoting illegal immigration. However, Indian government census reports note a decline in immigration from Bangladesh between 1971 and 2011.[73][74] According to Sanjoy Hazarika, a former Assamese journalist, the local media is coverage of so-called "Bangladeshis" to scaremongering.[14]

The response to the alleged illegal migration by Bangladeshis in India has seen double standards. In 2014 Narendra Modi, the then Prime minister hopeful threatened to expel all "illegal Bangladeshis" but made a distinction between Bengali Hindus and Muslims. Modi remarked that "those who are forced to flee Bangladesh and are sons of mother India, love the nation, worship (the Hindu goddess) Ma Durga.....they will be protected and given the same status as other sons of mother India. But illegal Bangladeshi migrants, who are being brought to India in the name of vote-bank politics, will have to go back to Bangladesh."[75] In 2016, Narendra Modi's government proposed the Citizenship Amendment Bill which allow illegal immigrants including Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Jains, Parsis and Buddhists to become Indian citizens easily, but not Muslims.[14]

See also

Other Bengali religious groups

Other Muslim ethnic groups

References

- ↑ Muslim population in Bangladesh excluding Urdu-speakers

- ↑ 24.6 million Muslims in West Bengal and 10.7 million Muslims in Assam

- ↑ "Five million illegal immigrants residing in Pakistan". Express Tribune.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word — Cover_Kapiszewski.doc" (PDF). Un.org. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Labor Migration in the United Arab Emirates: Challenges and Responses". Migration Information Source. 18 September 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Malaysia cuts Bangladeshi visas". BBC News. 11 March 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ↑ CT0341_2011 Census - Religion by ethnic group by main language - England and Wales ONS.

- ↑ "Bangladeshis storm Kuwait embassy". BBC News. 24 April 2005.

- ↑ "Oman lifts bar on recruitment of Bangladeshi workers". News.webindia123.com. 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Snoj, Jure (18 December 2013). "Population of Qatar by nationality". Bqdoha.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ "In pursuit of happiness". Korea Herald. 8 October 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "The Calcutta Review". 1 January 1941 – via Google Books. [Mussalman also used in this work.]

- ↑ Choudhury, A. K. (1 January 1984). "The Independence of East Bengal: A Historical Process". A.K. Choudhury – via Google Books. [Mussalman also used in this work.]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Andre, Aletta; Kumar, Abhimanyu (23 December 2016). "Protest poetry: Assam's Bengali Muslims take a stand". Aljazeera. Aljazeera. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ↑ Meghna Guhathakurta; Willem van Schendel (2013-04-30). "The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- 1 2 3 Mohammad Yusuf Siddiq (2015-11-19). Epigraphy and Islamic Culture: Inscriptions of the Early Muslim Rulers of ... Books.google.com. p. 30. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- 1 2 3 Eaton, Richard Maxwell (1 January 1996). "The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760". University of California Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Ali, Mohammad Mohar (1988). History of the Muslims of Bengal, Vol 1 (PDF) (2 ed.). Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University. pp. 683, 404. ISBN 9840690248. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mukhapadhay, Keshab (13 May 2005). "An interview with prof. Ahmed sharif". News from Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ↑ "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". Pewforum.org. 9 August 2012.

- ↑ Richard Maxwell Eaton. The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Bengali language | Britannica.com". Global.britannica.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Ancient mosque unearthed in Bangladesh". Al Jazeera English. 2012-08-18. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Arabs, The — Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. 2014-06-17. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Coins — Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. 2015-03-04. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Hussain, Syed Ejaz (1 January 2003). "The Bengal Sultanate: Politics, Economy and Coins, A.D. 1205-1576". Manohar – via Google Books.

- ↑ Shoaib Daniyal. "Bengali New Year: how Akbar invented the modern Bengali calendar". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "The paradise of nations | Dhaka Tribune". Archive.dhakatribune.com. 2014-12-20. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Ghosh, Shiladitya. "Transitions – History and Civics – 8". Vikas Publishing House – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Hissam Khandker. "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- 1 2 Richard Maxwell Eaton (1997-10-01). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Farooqui Salma Ahmed. A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Books.google.com. p. 366. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- 1 2 Khan, Muin-ud-Din Ahmed (2012). "Faraizi Movement". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- ↑ Kabir, Nurul (1 September 2013). "Colonialism, politics of language and partition of Bengal PART XV". New Age. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ↑ "Do we know anything about Lahore Resolution?". Alarabiya.net. 2009-03-24. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Mitra, Subrata Kumar; Enskat, Mike; Spiess, Clemens (2004). Political Parties in South Asia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-0-275-96832-8.

- ↑ Harun-or-Rashid (2012). "Bangladesh Awami League". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Political Parties in South Asia. Books.google.com. p. 217. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Lewis, David (2011). Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75, 83. ISBN 978-0-521-71377-1.

- ↑ "Bangladesh" (PDF). U.S. State Department. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Understanding the Bengal Muslims Interpretative Essays Hardcover". Irfi.org. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "The Future of the Global Muslim Population | Pew Research Center". Pewforum.org. 2011-01-15. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Bengal beats India in Muslim growth rate — Times of India". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Topich, William J.; Leitich, Keith A. (1 January 2013). "The History of Myanmar". ABC-CLIO – via Google Books.

- ↑ Dizikes, Peter. "The hidden history of Bengali Harlem". MIT News Office. MIT. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ "Zainuddin, Sheikh - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ↑ Hasan, Perween (2007). Sultans and Mosques: The Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh. I.B.Tauris. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God". Abc-Clio.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Sufism Journal: Community: Sufism in Bangladesh". sufismjournal.org.

- ↑ Banu, U.A.B. Razia Akter (1992). Islam in Bangladesh. New York: BRILL. pp. 34–35. ISBN 90-04-09497-0. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Milam, William B. (4 July 2014). "The tangled web of history". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ Eaton, Richard M. (1993). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. University of California Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-564173-8.

- ↑ Versteegh, C. H. M.; Versteegh, Kees (2001). The Arabic Language. Edinburgh University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-7486-1436-3.

- ↑ "BENGAL – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "The development of Bengali literature during Muslim rule" (PDF). Blogs.edgehill.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Karim, Abdul (2012). "Nur Qutb Alam". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- 1 2 3 Rizvi, S.N.H. (1965). "East Pakistan District Gazetteers" (PDF). GOVERNMENT OF EAST PAKISTAN SERVICES AND GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT (1): 353. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ Ahmed, Wakil (2012). "Sufi Literature". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Billah, Abu Musa Mohammad Arif (2012). "Persian". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Huq, Khondkar Serajul (2012). "Muslim Sahitya-Samaj". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Kendriyo_Muslim_Sahitya_Sangsad

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Muslim_Sahitya-Samaj

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangiya_Mussalman_Sahitya_Samiti

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangiya_Sahitya_Bisayini_Mussalman_Samiti

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Mohammedan_Literary_Society

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Purba_Pakistan_Sahitya_Sangsad

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Pakistan_Sahitya_Sangsad,_1952

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Uttar_Banga_Sahitya_Sammilani

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Rangapur_Sahitya_Parisad

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangiya_Mussalman_Sahitya_Patrika

- ↑ ><!. "CJI Altamas Kabir retires today". Madhyamam.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Roy, Sandip (16 August 2012). "The illegal Bangladeshi immigrant: Do the bogeyman numbers add up" (1). Firstpost. Firstpost. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ Deka, Dr. Kaustubh (3 June 2014). "BJP leaders warn illegal Bangladeshis to leave, but census figures refute the myth of large-scale infiltration Rate of growth of Assam's population has been declining since 1971" (1). Scroll.in. Scroll.in. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ Jayasekera, Deepal. "Modi reiterates pledge to expel "Bangladeshi" Muslims in wake of communal massacre". World Socialist Website. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Rafiuddin (1996). The Bengal Muslims, 1871–1906: a quest for identity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563919-3.

- Ahmed, Rafiuddin (2001). Understanding the Bengal Muslims: interpretative essays. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-565520-9.

- Bald, Vivek (2013). Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07040-0.

- Chakraborty, Ashoke Kumar (2002). Bengali Muslim literati and the development of Muslim community in Bengal. Indian Institute of Advanced Study.

- Lahiri, Pradip Kumar (1991). Bengali Muslim thought, 1818–1947: its liberal and rational trends. K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 978-81-7074-067-4.

- Sinha, Soumitra (1995). The Quest for Modernity and the Bengali Muslims: 1921 – 47. Minerva Pub. ISBN 978-81-85195-68-1.

- Shah, Mohammad (1996). In search of an identity: Bengali Muslims, 1880–1940. K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 978-81-7074-184-8.