Mru people

| တောင်မြိုလူမျိုး | |

|---|---|

Mru family in a traditional household | |

| Total population | |

| 80,000–85,000 (2004, est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Myanmar, Rakhine State), Bangladesh (Chittagong Hill Tracts), India (West Bengal) | |

| 12,000[1] | |

| 20,000–25,000[1] | |

| 20,000[1] | |

| Languages | |

|

Mru (dialects: Anok, Dowpreng, Sungma)[2] Bengali Burmese | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, Buddhism and Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chin people | |

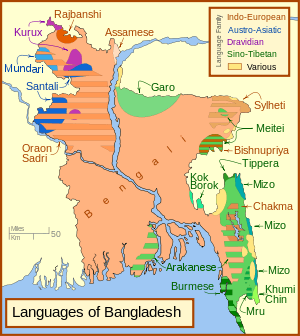

The Mru (Burmese: တောင်မြိုလူမျိုး; Bengali: মুরং), also known as the TaungMro, the Mrung, and the Mrucha, refer to the tribes who live in the border regions between Myanmar (Burma), Bangladesh, and India. The Mru are a sub-group of the Chin people, the majority of whom live in western Myanmar. They are also found in the southern Chin State and northern Rakhine State. In Bangladesh, they reside in the Chittagong Hills in southeast Bangladesh, primarily in Bandarban District and Rangamati Hill District. In India, they reside in the districts of west Bengal.[1]

.jpg)

Origin

Locally, the Mro are known as Mrucha in Bangladesh and as Taung-Mros in Rakhine State. They claim that their ancestors lived at the source of the Kaladan River, but are unsure about when their people migrated to the region. They have no division of different exogamous clans or groups of clans, nor do they have a chieftain class or a ruling class.

The origin of the Mro cannot be fully depicted without including the Khami (Khumi) people. Due to frequent invasions by the Shandu and subsequent colonization by the British, the Ahraing Khami (Khumi) left their homeland. They emigrated to the hilly regions of the Kaladan River headwaters and to the Pi Chaung and the Mi Chaung streams in the Arakan Hill Tracts where another group of Khami (Khumi),the Mro (Mrucha) and Ahraing Khami (Khumi), lived. To escape the Ahraing Khami (Khumi), the Mro (Mrucha) and Mro (Awa Khami) migrated to the Chittagong Hill Tracts where they currently reside.[3]

According to legend, the hilly region was once ruled by Nga Maung Kadon who built the barriers which form the waterfalls in all the streams and tributaries connected to the Kalapanzin River. He did this to prevent the escape of a crocodile that had kidnapped his wife.[4]

Geography

In Burma, the Mro (Mrucha), along with Ahraing Khami (Khumi) and Mro (Awa Khami), live in the Buthidaung Chin Hill Area (Saingdin) along with two other tribes, known as, Chaungthas and Daingnets. However, the Mro (Mrucha) and Mro ( Awa Khamis) are the oldest tribes living in the region. Together, they form the largest percentage of the population of the approximately 230 square mile Saingdin region.[4] The two main streams that flow through Saingdin are Re Chaung in the east and Sit Chaung in the west. Both streams originate from the northern part of the region which forms the boundary between Buthidaung Township and the Arakan Hill Tracts. The two streams meander between cliffs for 30 miles before they finally join together near the Tharaungchaung village. The two streams flood during the monsoon season and normally subside after the rains. Water transportation is difficult due to large rocks obstructing the streams. Canoes and bamboo rafts are the only means of transportation to the interior area of the region.[4] On the sloping banks of the two streams, the Mro (Mrucha) grow tobacco in the alluvial deposit after clearing naturally grown kaing grass. They also grow paddy, cotton, cane, and bamboo to sell in a weekly bazaar near the waterfall.[4]

Demographics

As of 1931, the Saingdin area consists of 90 hamlets and each hamlet contains between two and 20 bamboo houses.[4] The population, according to the 1931 Census is 3,390, of which 1,779 are males.[4] Currently, about 70,000 Mro (Mrucha) live on the border of Burma with India and Bangladesh. The majority of Mro (Mrucha) people, approximately 12,000, live in Burma within the Yoma District and the Arakan Hill Tracts of western Burma. These figures are, however, just rough estimates as the last census was conducted in 1931 when the country was under the colonial rule. At that time, the total number of Mro (Mrucha) people was estimated around 13,766. Around 200 more villages making up of between 20,000 to 25,000 people are located in the Chittaung Hills of southern Bangladesh. Another 2,000 Mros inhabit the districts of West Bengal, India. It is estimated that the population will grow to 85,700 by 2020.[1]

Language and script

| Mru Mro, Krama[5] | |

|---|---|

| Type |

alphabet

|

| Languages | Mru |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Mroo, 264 |

Unicode alias | Mro |

| U+16A40–U+16A6F | |

They primarily speak the Mru language, a Sino-Tibetan language, and one of the recognised languages of Bangladesh. The Mru language is considered "definitely endangered" by UNESCO in June 2010.[6] The language of the Mru can be classified under Sino-Tibetan or Tibeto-Burman linguistic group. Dialects include Anok, Downpreng and Sungma. It has 13% lexical similarity with Khami and 72%–76% with Anu-Hkongsu. In Bangladesh, around 91% – 98% of the population speaks Downpreng and Sungma dialects. Both Latin and Mru alphabets, formed in 1980s, are used in writing even though the latter is more commonly used for the literacy development. It is also categorised as a developing language.[2]

Religion

Buddhism

In the modern days, the Mro (Mrucha) practise both animism and Buddhism. A strong Buddhist influence exists with about 80% of the population adhering to Theravada Buddhism, a common sect of Buddhism eminent throughout mainland Southeast Asia, especially in Burma and Thailand. In Bangladesh, however, there is less Buddhist influence and in India, most of the Mro are Hindus.[1]

Christianity

Only 7.4% of the Mro (Mrucha) adhere to Christianity, though 64% have heard the gospel. The New Testament was translated into Mru language in 1994. In 1997, an incident occurred that made a considerable number of the Mru convert to Christianity. Buddhist monks led a gang of men to the Christian villages, and burned down the churches and pastors' homes and beat the villagers. However, as the group crossed a mountain pass on their way to the first Mro (Mrucha) village, they were struck by lightning. Another bolt struck the 300-year-old Buddhist temple, burning it to the ground. A second gang of persecutors sailed to another Christian village on the bank of the river by raft. As they floated through the river, a heavy fog settled, severely impeding the visibility. The boat then was crashed into by a fast-floating barge, sinking it and causing several people to drown. When the news spread to the Mro (Mrucha) villages in the area, most of them decided to convert to Christianity.[1]

Khrama

In the 1980s Menlay Murang (also known as Manley Mro) created the religion of Khrama (or Crama) and with it a new alphabet for the Mru language.[7][8]

Cosmological beliefs

The Mro (Mrucha) believe that earthquakes are caused by a dragon, that wants to test whether people are still in existence. They also believe that a thunderbolt is thrown by a powerful nat to a less powerful nat who resides in the tree that the thunderbolt strikes. Legends concerning the sun, moon stars and comets do not exist in the Mro (Mrucha). However, they do hold a belief regarding the eclipse of the sun. The legend goes like this: Long ago, a woman in their village gave birth to a son without a father. As soon as the son came out of his mother's womb, he dug out 7 rats from the ground and devoured them. Then he asked his mother who his father was. As his mother did not want to upset her son, she told him his father was killed by a tiger. Then the son went into the jungle and killed a tiger with a spear. He brought back the head of the tiger and used it as a pillow for a night, beseeching it to show father at night. However, there was no sign of his father after the sunrise. He then went back to his mother and asked her where his father was. This time, his mother told him a different story. She said his father died of a heat stroke due to the extremely hot sun. The son then told the villagers that he would go and wage a war against the sun and urged them to join whenever they see the eclipse of the sun. Because of this belief, the Mru sing war cries whenever a sun eclipse takes place.[4]

Taungya

The Mro (Mrucha), just like many other ethnic groups from the hilly regions of Southeast Asia, practice [taungya] cultivation. They cultivate on the hillsides after cutting down the trees, which usually takes them a month. This process usually occurs in January or February. Around March, they burned the trees that are taken down for taungya paddy cultivation and they start sowing at the wind of April. When they sow the seeds separately in pits, they would use spades, which are made with a long handle from an old taungya-cutting-dah (knife) that is no longer usable.[9]

Traditional rites and rituals

Birth

After a birth of a child, four short bamboos are placed on the bank of the stream. A chicken is then killed in the honour of the nats and its blood poured over the bamboos that are put close together. A prayer is then made for the well-being of the child. The chicken is then dumped.[10]

New Taungya Cutting

Before the start of a new taungya cultivation, the villagers collectively buy two goats, and two fowls gathered from each household. One of the goats is put in front of the hut closest to the stream and the other near the second hut. The fowls are then placed in between the two huts. After the villagers pray for good health and the abundance of crops for the coming taungya cultivation, both the goats and fowls are slaughtered one after another starting from the goat nearest to the stream. The blood of the animals is then sprayed over the small huts and the flowing water. The villagers then cooked the goats and the fowls are reclaimed by their respective owners. With the meat and khaung, they made an offering to the nat before they begin the feast. Meanwhile, the village is shut down for three days and the villagers fix up bamboo arches over the village path. If anyone enters the village during this time period, a compensation has to be paid to cover all the expenses incurred. This ceremony is celebrated once a year and after the ceremony, they can start their taungya cultivation for the year.[11]

Beginning of Taungya Harvest

After the taungya fruits and vegetables are ready for the harvest, household members go into their taungyas and collect several different vegetables and fruits with a few plants of paddy. The vegetables and fruits are then put into a big basket and paddy into khaung pot. A fowl is then killed and its blood sprinkled over the khaung pot and the vegetable basket. Another fowl is cooked using rice flour and mixing it with salt and ginger. Then the rice is mixed with the khaung and then together with the fowl, they made offering in various different baskets to the nats who live in the staircase of the house. Neighbors are then invited to enjoy the rest of the meat. This natpwe is held on the same day by different households in a village. Villagers can harvest their produce after the ceremony.[11]

End of Taungya Harvest

After all the crops have been harvested, every household kills a pig or two and cooks some pieces of pork in a bamboo tube. The household members then take the meat along with rice and khaung to their taungya. Once they arrived at their taungya, offerings are made to various nats roaming near the streams close to the taungya. They then pray to the nats for their physical well-being. After they return home, they threw a feast with the rest of the pork and khaung. This pwe is also celebrated on the same day by all the villagers.[11]

Funeral

When a Mro (Mrucha) dies a natural death, his body is put in a coffin made of split coloured bamboos. A pig is then slaughtered and its blood sprayed over the coffin. The pig is then offered to the funeral attendees. The body is then cremated. The remaining unburnt pieces of bones are collected and placed on a platform in the cemetery along with khaung and other food for the deceased to enjoy. In the case of an unnatural death, the body is buried without killing a pig. If it is a death of a toddler up to 3 years of age, a dog is killed and its body placed in the coffin with the child's body. Then the corpse is cremated without the body of the dog. The same procedure of placing food and khaung for the dead person follows suit while the dead body of the dog is dumped in the cemetery. In any case, no stone cairn or shelter over the grave is built. The head and the body are not separated as well. In the case of unnatural death of a spouse, he or she will only eat vegetables for forty days after leaving their house and all the belongings permanently. In some cases, the widow or the widower would live only on rice and water in a hut specially built for the purpose and is not allowed to sit together with others, only converse with them.[12]

Marriage law

The man usually discusses his father about the woman he intends to marry and the father along with his son and a few other villagers visits the house of the prospective bride. They would bring three fowls, a spear and a dah (dagger) with them and the spear and the dah are given to the bride's parents as presents and the fowls for the family to eat. In return, the bride's family cooks pork for the visitors. The visitors must not eat the fowls and the hosts the pork. The bride's father then consults with her daughter and after getting her consent, asks for a dowry. Back in 1931, it usually consisted of around Rs. 100 and the groom's father may not bargain. After the dowry is settled, the groom's party stays for three days, feasting on khaung and leave the next day.[13] However, in case of a marriage, contracted between the couple without the parental consent, for instance, in a case in which a lad elopes with a woman to his parent's house, the parents, with the village elders, return the bride to her parents along with three fowls and khaung. The groom's parents then ask what dowry the bride's parents would like to accept. The dowry, in this case, can be as high as Rs. 100 or as low as Rs. 30. Similar procedures as the one mentioned above take place, expect that the groom's family does not stay over for a night but return home with the couple. Then the marriage date is chosen. The bride visits her home occasionally but never returns there permanently. If either party breaks the promise of marriage, no action is taken as long as either the bride or the groom claims that one does not love the other. If the bride breaks the promise, half of the dowry has to be returned whereas if the groom breaks the promise, his family loses the dowry. If the husband dies, the heir is entitled to nothing; she has to abandon the issue of marriage, if any, with her father-in-law or a brother-in-law.[14]

Dress

The males wear Burmese jackets, called "Kha-ok", bought from Indian hawkers. They then cover the lower part of the body with a loin-cloth, which is tied around the waist twice and pass it between the thigh with both ends hanging downwards, one at the front and the other at the back. Then they would wear a cloth on the head without covering the top of the hair. This cloth is also sold by Indian hawkers. The loin cloth is made by themselves from the yarn, purchased from Indian hawkers. Unlike Mro (Awa Khami) women who wear a piece of cloth covering the breast and the back. The Mro (Mrucha) women, before marriage, are topless with the lower part of the body covered by a short cloth. The skirt is woven from the yarn, obtained from Indian merchants. Some women of considerable wealth add a string of copper pieces to the string of beads around the waist. They also wear silver earrings, which are hollow tubes about three inches long.[15]

Chiasotpoi

One of the biggest social rites of the Mro (Mrucha) people is Chesotpoi. At least one cow or more are sacrificed in devoting the sacred spirit intending free from ill or any curse that has been suffered. A full night dancing and playing ploong take places and follows up to the full next day. After full night dance, early in the morning, the cow is killed by spear. Then the cow's tongue is cut off. Villager then move to sit on the body of the cow putting turban on head. Rice beer or alcohol is served during the fest. After cooking the meat and mostly all parts of the cow all villagers come together and enjoy the feast with joy. There is no fixed time for the ceremony as anybody who afford can organize it anytime. Guests are happily allowed to take it part. On 28 December 2017 I happened to take the ceremony in Sakoi Commander para (village) of Thanchi with 4 other friends. While attending, I asked an elder Mro in the venue why this cow killing ceremony? He told me a legendary as follows: ''Long time ago, almighty summoned Mro people to take their letters. In that time all the people were so busy with work. For bringing the letters, they send a cow. Cow according to their order went, received and then set to move back. On the half way, the cow felt so hungry and took rest under a fig tree. During then, unconsciously the letter plate was swallowed down into her stomach. On return the Mro (Mrucha) people came to know the story of losing the letters and fired on the cow. The chief of the Mro (Mrucha) first hit the mouth, thus all the upper teeth of the cow were broken. While the almighty spirit cross checked, they complain the swallowing incident and the spirit asked them to punish the cow by act anything they want to. And that was proclaimed as No Sin. Hence, the angered Mro (Mrucha) people decided to kill the cow and then cut off the tongue as punishment. Thus the ceremony started and being regarded as one of the highest ought of all the rituals they follow. And you see, it why the cow has no upper teeth yet''.

Musical instruments

Among the distinctive cultural aspects of the Mro is the ploong, a type of mouth organ made of a number of bamboo pipes, each with a separate reed.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hattaway, Paul (2004). Peoples of the Buddhist World: A Christian Prayer Diary (PDF). Pasadena, CA: William Carrey Library. p. 195. ISBN 9780878083619.

- 1 2 Lewis, Simons, and Fennig, M. Paul, Gary F. and Charles D. "Ethnologue: Languages of the World". SIL International. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 204.

- ↑ Mru at Ethnologue (17 ed.). 2013.

- ↑ UNESCO, "Bangladesh: Some endangered languages (information from Ethonologue, UNESCO)" Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine., June 2010.

- ↑ Hosken, Martin; Everson, Michael (24 March 2009). "N3589R: Proposal for encoding the Mro script in the SMP of the UCS" (PDF). Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ Zaman, Mustafa (24 February 2006). "Mother Tongue at Stake". Star Weekend Magazine. The Daily Star. 5 (83).

- ↑ Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 251.

- ↑ Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 252.

- 1 2 3 Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 253.

- ↑ Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 260.

- ↑ Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 255.

- ↑ Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 208.

- ↑ Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 258.

- ↑ Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham (2000). World Music: Latin and North America, Caribbean, India, Asia and Pacific. Rough Guides. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-1-85828-636-5.

- "Profile of the Mru, Mro", Joshua Project

- Brauns, Claus-Dieter, "The Mrus: Peaceful Hillfolk of Bangladesh", National Geographic Magazine, February 1973, Vol 143, No 1

Further reading

- "Indigenous Peoples Development Planning Document: Indigenous Peoples Development Plan: Bangladesh: Chittagong Hill", Asian Development Bank

- "Become Acquainted With The Peace-Loving Mru", bangladesh.com

- "From the land of the sunrise", Dhaka, Bangladesh, 18–24 August 2006, Life & Struggles of the Mro People in Bangladesh.

- van Schendel, Willem, "A Politics of Nudity: Photographs of the ‘Naked Mru’ of Bangladesh", Modern Asian Studies, 36, 2 (2002), pp. 341–374. Cambridge University Press

- Chowdhury, Mohammad Shaheed Hossain; et al., "Indigenous knowledge in natural resource utilization by the hill people: A case of the Mro tribe in Bangladesh"

- Brauns, Claus-Dieter; Löffler, Lorenz G., Mru: hill people on the border of Bangladesh, Birkhäuser Verlag, 1990

- "Asian People Group Profiles: Bangladesh: The Mru", Asia Harvest

- Peterson, David A., "Where does Mru fit into Tibeto-Burman?", The 42nd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (ICSTLL 42), November 2009, Payap University, Chiangmai, Thailand. Cf. p. 14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mru people. |

- "Meet the indigenous people of the Bandarban Hilltracts, The Mru: A hidden tribe", Bangladesh EcoTours