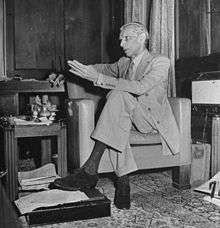

A. K. Fazlul Huq

Abul Kasem Fazlul Huq (26 October 1873—27 April 1962);[1] was a Bengali lawyer, legislator and statesman in the 20th century. Huq was a major political figure in British India and later in Pakistan (including East Pakistan, which is now Bangladesh). He was one of the most reputed lawyers in the High Court of Calcutta and High Court of Dacca. Born in Bakerganj, he was an alumnus of the University of Calcutta. He worked in the regional civil service and began his political career in Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1906.

Huq was first elected to the Bengal Legislative Council from Dacca in 1913; and served on the council for 21 years until 1934.[2] He was a member of the Central Legislative Assembly for 2 years, between 1934 and 1936.[2] For 10 ten years between 1937 and 1947, he was an elected member of the Bengal Legislative Assembly, where he was Prime Minister and Leader of the House for 6 years.[2] He was later elected to the East Bengal Legislative Assembly, where he was Chief Minister for 2 months; and to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, where he was Home Minister for 1 year, in the 1950s.

Huq boycotted titles and knighthood granted by the British government. He is popularly known with the title of Sher-e-Bangla (Lion of Bengal). He was notable for his English oratory during speeches to the Bengali legislature.[3] Huq courted the votes of the Bengali middle classes and rural communities. He pushed for land reform and curbing the influence of zamindars.[4] Huq was considered a leftist and social democrat on the political spectrum. His ministries were marked by intense factional infighting. In 1940, Huq had one of his most notable political achievements, when he presented the Lahore Resolution. During the Second World War, Huq joined the Viceroy of India's defence council and supported Allied war efforts. Under pressure from the Governor of Bengal during the Quit India movement and after the withdrawal of the Hindu Mahasabha from his cabinet, Huq resigned from the post of premier in March 1943. In the Dominion of Pakistan, Huq worked for five years as East Bengal's attorney general and participated in the Bengali Language Movement. He was elected as chief minister, served as a federal minister and was a provincial governor in the 1950s.

Huq became secretary of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League in 1913. In 1929, he founded the All Bengal Tenants Association, which evolved into a political platform, including as a part of the post-partition United Front. Huq held important political offices in the subcontinent, including President of the All India Muslim League (1916-1921), General Secretary of the Indian National Congress (1916-1918), Education Minister of Bengal (1924), Mayor of Calcutta (1935), Prime Minister of Bengal (1937-1943), Advocate General of East Bengal (1947-1952), Chief Minister of East Bengal (1954), Home Minister of Pakistan (1955-1956) and Governor of East Pakistan (1956-1958). Huq was fluent in Bengali, English and Urdu, and had a working knowledge of Arabic and Persian.[2] Huq died in Dacca, East Pakistan on 27 April 1962. He is buried in the Mausoleum of Three Leaders. The Sher-e-Bangla Nagar area of Dhaka, which houses the National Parliament, is named after Huq. The Sher-e-Bangla Cricket Stadium is also named after him.

Early life and education

Huq was born into a middle class Bengali Muslim family in Bakerganj in 1873. He was the son of Muhammad Wazid, a reputed lawyer[1] of the Barisal Bar, and Sayedunnessa Khatun. His paternal grandfather Kazi Akram Ali was a Mukhtar and a scholar of Arabic and Persian. Initially home schooled,[1] he later attended the Barisal District School, where he passed the FA Examination in 1890. Huq moved to Calcutta for his higher education.[1] He sat for his bachelor's degree exam in 1894, in which he achieved a triple honours in chemistry, mathematics and physics from the Presidency College now (Presidency University). He then obtained a master's degree in mathematics from the University of Calcutta in 1896. He obtained his Bachelor in Law from the University Law College in Calcutta in 1897.[5]

Civil servant and lawyer

From 1908 to 1912, Huq was the Assistant Registrar of Co-operatives. He resigned from public service and opted for public life and law. Being advised by Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee, he joined the bar council of the Calcutta High Court and started legal practice.[2] He practiced in the Calcutta High Court for 40 years.

Legislator

After the First Partition of Bengal, Huq attended the All India Muhammadan Educational Conference hosted by Sir Khwaja Salimullah in Dacca, the erstwhile capital of Eastern Bengal and Assam. The conference led to the formation of the All India Muslim League. The annulment of the partition led to the formation of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League, in which Huq became secretary. With the patronage of Sir Salimullah and Syed Nawab Ali Chowdhury, he was elected to the Bengal Legislative Council from Dacca Division in 1913.

In 1916, Huq was elected president of the All India Muslim League. Huq was one of those who were instrumental behind formulating the Lucknow Pact of 1916 between the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League. In 1917 Huq was a Joint Secretary of the Indian National Congress and from 1918-1919 he served as the organization’s General Secretary. He is the only person in history to concurrently hold the presidency of the League and the general secretary's position in the Congress. In 1918, Huq presided over the Delhi Session of the All India Muslim League.[2]

In 1919, Huq was chosen as a member of the Punjab Enquiry Committee along with Motilal Nehru, Chittaranjan Das and other prominent leaders set up by the Indian National Congress to investigate the Amritsar massacre. Huq was the president of the Midnapore Session of the Bengal Provincial Conference in 1920.[2]

During the Khilafat movement, Huq led the pro-British faction within the Bengal Provincial Muslim League, while his rival Maniruzzaman Islamabadi led the pro-Ottoman faction. Huq also differed with the Congress leadership during its non-cooperation movement. Huq favored working within the constitutional framework rather than boycotting legislatures and colleges. He later resigned from the Congress.

In 1924, Huq served as education minister of Bengal for six months under the dyarchy system.

Huq ministries

First Premiership (1937-1941)

The dyarchy was replaced by provincial autonomy in 1935, with the first general elections held in 1937. Huq transformed the All Bengal Tenants Association into the Krishak Praja Party. During the election campaign period, Huq emerged as a major populist figure of Bengal. His party won 35 seats in the Bengal Legislative Assembly during the Indian provincial elections, 1937. It was the third largest party after the Bengal Congress and Bengal Provincial Muslim League. The Congress refused to form government due to its pan-Indian policy of boycotting legislatures. Huq formed a coalition with the Bengal Provincial Muslim League and independent legislators. He was elected as the Leader of the House and the 1st Prime Minister of Bengal.

Huq’s cabinet include Nalini Ranjan Sarkar (finance), Bijoy Prasad Singha Roy (revenue), Maharaja Srish Chandra Nandy (communications and public works), Prasanna Deb Raikut (forest and excise), Mukunda Behari Mallick (cooperative credit and rural indebtedness), Sir Khwaja Nazimuddin (home), Nawab Khwaja Habibullah (agriculture and industry), Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (commerce and labour), Nawab Musharraf Hussain (judicial and legislative), and Syed Nausher Ali (public health and local self-government).[2]

In 1940, Huq was selected by Muhammad Ali Jinnah to formally present the Lahore Resolution, which envisaged ‘independent states’ in the eastern and northwestern parts of India.

One of the notable measures taken by Huq included using both administrative and legal measures to relieve the debts of peasants and farmers. He protected the poor agriculturists from the clutches of the usurious creditors by enforcing the Bengal Agricultural Debtors' Act (1938). He established Debt Settlement Boards in all parts of Bengal. The Money Lenders' Act (1938) and the Bengal Tenancy (Amendment) Act (1938) improved the lot of the peasants. The Land Revenue Commission appointed by the Government of Bengal on 5 November 1938 with Sir Francis Floud as Chairman, submitted the final report on 21 March 1940. This was the most valuable document related to the land system of the country. The Tenancy Act of 1885 was amended by the Act of 1938 and thereby all provisions relating to enhancement of rent were suspended for a period of 10 years. It also abolished all kinds of ABWAB and selamis (imposts) imposed traditionally by the zamindars on raiyats. The raiyats got the right to transfer their land without paying any transfer-fee to zamindars. The law reduced the interest rate for arrears of rent from 12.50% to 6.25%. The raiyats also got the right to get possession of the nadi sekasti (land lost through river erosion and appeared again) land by payment of four years of rent within twenty years of the erosion. Thus several acts enforced during Huq's Premiership helped the peasants to lighten some of their burdens though Huq could not fully execute his programme of Dal-Bhat placed before the people during his election campaigns. Huq also promoted affirmative action for Bengali Muslims.[2]

Huq held the education portfolio in his cabinet. He introduced the Primary Education Bill in the Bengal Legislative Assembly, which was passed into law and made primary education free and compulsory. But there was a storm of protests from the opposition members and the press when Fazlul Huq introduced the Secondary Education Bill in the assembly as it incorporated 'principles of communal division in the field of education' at the secondary stage. Huq was associated with the foundation of many educational institutions in Bengal, including Calcutta's Islamia College and Lady Brabourne College, Wajid Memorial Girls' High School and Chakhar College.

Due to intense factional infighting within the Krishak Praja Party, that Huq ended up being the lone party member on the cabinet. After 1939, the British Empire grappled with World War II. In 1941, Huq and Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, the Prime Minister of the Punjab, joined the Viceroy's National Defence Council. Their move angered Muhammad Ali Jinnah because they had not consulted him, and because it deviated from the Muslim League party line that the structure of the council was unacceptable inasmuch as it did not give the League parity with Congress.[6]

On 2 December 1941, Huq resigned and governor’s rule was imposed.

Second Premiership (1941-1943)

The second Huq coalition government was formed on 12 December 1941. The coalition was supported by most members in the Bengal Legislative Assembly, except for the Muslim League. Supporters included the secular faction of the Krishak Praja Party led by Shamsuddin Ahmed, the Forward Bloc founded by Subhash Chandra Bose, pro-Bose members of the Bengal Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha led by Syama Prasad Mukherjee. The cabinet included Nawab Bahabur Khwaja Habibullah, Khan Bahadur Abdul Karim, Khan Bahadur Hashem Ali Khan, Shamsuddin Ahmed, Syama Prasad Mukherjee, Santosh Kumar Bose and Upendranath Barman.[2]

Despite Huq enjoying the confidence of most of the assembly, he had tense relations with the Governor of Bengal John Herbert. The governor favored the provincial Muslim League leaders and patrons, including Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin, the Leader of the Opposition; and the "Calcutta Trio" in the assembly, including Mirza Ahmad Ispahani, Khwaja Nooruddin and A. R. Siddiqui. The focal point of the League's campaign against Huq was that he was growing closer with Mukherjee, who was alleged to be working against the political and religious interests of the Muslims. The League appealed to the governor to dismiss the Huq ministry.

The fear of Japanese invasion during the Burma Campaign and the implementation by the military of a 'denial policy' implemented in 1942 caused considerable hardship to the delta region. A devastating cyclone and tidal waves whipped the coastal region on 26 October but relief efforts were hindered due to bureaucratic interference. On 3 August, a number of prisoners were shot down in Dhaka jail but no inquiry could be held again due to bureaucratic intervention. Another severe strain on the administration was caused when the Congress launched the Quit India movement on 9 August, which was followed by British political repression. The entire province reverberated with protest. The situation was further complicated when Mukherjee resigned bitterly complaining against the interference of the governor in the work of the ministry.

On 15 March 1943, the Prime Minister disclosed in the floor of the Assembly that on several occasions, under the guise of discretionary authority, the governor disregarded the advice tendered by the ministry and listed those occasions. The governor did not take those allegations kindly, and, largely due to his initiative, no-confidence motions were voted in the assembly on 24 March and 27 March. On both occasions the motions were defeated, although by narrow margins. To enforce his writ, the governor asked Huq to sign a prepared letter of resignation on 28 March 1943 and assigned himself the responsibility of administering the province under the provision of Section 93 of the constitution. A month later a League dominated ministry was commissioned with Nazimuddin as the Prime Minister. Huq’s party won much fewer seats during the Indian provincial elections, 1946.

Political career in Pakistan

Advocate General and Language Movement

After the partition of British India, Huq settled in Dhaka and became the Advocate General of the Government of East Bengal.[2] He served in the position between 1947 and 1952. On 31 December 1948, while delivering a presidential address at a literary conference, Huq proposed a language academy for the Bengali language.[7] He supported the Bengali Language Movement in 1952. Huq was also injured during police action against demonstrators demanding that Bengali be made a state language of Pakistan.

Chief ministership

Huq was a leading figure in the United Front (East Pakistan) coalition along with Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and Maulana Bhashani. The United Front won a landslide victory during the East Bengali legislative election, 1954. Huq himself defeated his arch rival Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin in the Patuakhali constituency.

Huq became chief minister for two months. During his short lived ministry, he took measures to establish the Bangla Academy. King Saud of Saudi Arabia sent a plane to Dhaka to bring Huq for a meeting with the monarch in Karachi.[8]

A report in The New York Times stated that Huq wanted independence for East Bengal, which trigged his dismissal and the imposition of Governor General’s rule. Huq was subsequently placed under house arrest.

Central ministership

In August 1955, a coalition between the Krishak Sramik Party in East Pakistan and the Muslim League in West Pakistan allowed Chaudhry Mohammad Ali to become Prime Minister and A. K. Fazlul Huq to become the federal Home Minister.[9] Prime Minister Ali was later dismissed by President Iskander Mirza, who allowed a coalition of the Awami League and Republican Party to form government. As a result, the Krishak Sramik Party and the Muslim League formed the main opposition.[10]

Governorship

Huq was appointed Governor of East Pakistan in 1956. He served in the position for two years until the 1958 Pakistani coup d'état. Huq was again placed under house arrest after the coup.

Notable quotations

Quotes by Huq

I am the living history of Bengal and East Pakistan of the last sixty years. I am the last survivor of that band of unselfish and courageous Muslims who fought fearlessly against terrific odds…[11]

On his role in the politics of Bengal (particularly Bangladesh)

I want you to consent to the formation of a Bengali Army of a hundred thousand young Bengalis consisting of Hindu and Muslim youths on a fifty-fifty basis. There is an insistent demand for such a step being taken at once, and the people of Bengal will not be satisfied with any excuses. It is a national demand which must be immediately conceded.[12]

Writing to Governor John Herbert regarding demands for forming a Bengal Army during World War II

Administrative measures must be suited to the genius and traditions of the people and not fashioned according to the whims and caprices of hardened bureaucrats, to many of whom autocratic ideas are bound up with the very breath of their lives.[12]

In a letter to the Governor of Bengal

They were lions in their own days and we have the descendants of the lions of Indian journalism in our midst today. But the difference between the two classes of lions is very significant. Those were lions whose roars used to reverberate from Bengal across the seven seas to the homes of the British nation, but in the case of the present lions they are as docile as lions in a circus show. The roar of the lions of old used to make thrones tremble, but most of the present lions only know how to crouch beneath the throne and wag their tails in approbation of government policy.[12]

Commenting on critical journalists on the floor of the Bengal Legislative Assembly

Mr Speaker, I can jolly well face the music, but I cannot face a monkey. Mr. Speaker, I never mentioned any honourable member of this House. But if any honourable member thinks that the cap fits him, I withdraw my remark.[12]

A controversial remark against an opponent in the Bengal Legislative Assembly

Quotes about Huq

When the tiger arrives, the lamb must give away.[13]

Muhammad Ali Jinnah's comment while making way for Huq, who entered the hall, to address the All India Muslim League Lahore Resolution Session

He who in 1943 had wanted to see Nazimuddin and Suhrawardy bite the dust now shares the same stretch of earth with them. All three are buried, side by side, in the grounds of the Dhaka High Court. For a while, the two of them were called Prime Minister of Pakistan. Fazlul Huq was not. But only he was spoken of as the Royal Bengal Tiger.[14]

Rajmohan Gandhi on A. K. Fazlul Huq

Personal life

He was married three times. His first wife was Khurshid Begum with whom he had two daughters. The marriage ended in divorce. His second wife was Musammat Jannatunissa Begum who was from Howrah, West Bengal. They had no children. His third wife Khadija was from Meerut district, Uttar Pradesh. They had a son together, A. K. Faezul Huq, who played an active role in Bangladeshi politics.[15]

Legacy

Sher-e-Bangla founded several educational and technical institutions for Bengali Muslims, including Islamia College in Calcutta, Baker hostel and Carmichael hostel residence halls for Muslim students of the University of Calcutta, Lady Brabourne College, Adina Fazlul Huq College in Rajshahi, Eliot hostel, Tyler Hostel, Medical College hostel, Engineering College hostel, Muslim Institute Building, Dhaka Eden Girls' College Building, Fazlul Huq College at Chakhar, Fazlul Huq Muslim Hall (Dhaka University), Fazlul Huq Hall(Bangladesh Agricultural University, then East Pakistan Agricultural University), Sher-e-Bangla Hall (Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology) Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University (SAU) Dhaka-1207, Bulbul Music Academy and Central Women's College. Sher-e-Bangla had significant contribution in founding the leading university of Bangladesh: Dhaka University. During his premiership Bangla Academy was founded and Bengali New Year's Day (Pohela Boishakh) was declared a public holiday.[16]

Throughout Bangladesh, educational institutions (e.g., Barisal Sher-e-Bangla Medical College), roads, neighbourhoods (Sher-e-Bangla Nagor), and stadiums (Sher-e-Bangla Mirpur Stadium) have been named after him. This depicts the respect of the people for Sher-e-Bangla. One of the main roads in Islamabad A.K.M. Fazlul Haq Road is named after him.[17]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Gandhi, Rajmohan (1986). Eight Lives. SUNY Press. pp. 189–190. ISBN 0-88706-196-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Huq, AK Fazlul - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- ↑ Dharitri Bhattacharjee (2012-04-13). "It's Time Bengal Remembered a Certain Huq - The Wire". Thewire.in. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- ↑ Rachel Fell McDermott; Leonard A. Gordon; Ainslie T. Embree (15 April 2014). Sources of Indian Traditions: Modern India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Columbia University Press. p. 836. ISBN 978-0-231-51092-9.

- ↑ "Huq, AK Fazlul - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

- ↑ Banyopadhyaya, Sekhara (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. Orient Longman. pp. 445–446. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

Both Huq and Khan were censored in July 1941 when they agreed to join—without Jinnah's approval—the Viceroy's National Defence Council, which in terms of its membership structure did not recognise the Muslim claim of parity.

- ↑ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangla_Academy

- ↑ "Sher-e-Bangla: only leader concurrently President of All India Muslim League and the General Secretary of All India National Congress". Soc.culture.bangladesh.narkive.com. 2006-05-02. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

- ↑ Hafez Ahmed at http://www.thefinancialexpress-bd.com. "Mohan Mia, the forgotten child of history". Print.thefinancialexpress-bd.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ Salahuddin Ahmed (2004). Bangladesh: Past and Present. APH Publishing. p. 147. ISBN 978-81-7648-469-5.

- ↑ AK Fazlul Huq Jr (2014-04-26). "Sher-e-Bangla: The Tiger of Bengal". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

- 1 2 3 4 Syed Ashraf Ali. "Sher-e-Bangla: A natural leader". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

- ↑ "The Financialexpress-bd". Print.thefinancialexpress-bd.com. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ↑ "Sher-e-Bangla: The Tiger of Bengal | Dhaka Tribune". Archive.dhakatribune.com. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ↑ Gandhi, Rajmohan (1986). Eight lives : a study of the Hindu-Muslim encounter. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780887061967.

- ↑ "Great Politicians". Sher-e-Bangla AK Fazlul Huq (Krisak Proja Party). Muktadhara. 9 May 2001. p. 67. Archived from the original on 8 September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ↑ On the 49th death anniversary of the man who moved the resolution that eventually resulted in the creation of Pakistan, there is barely a mention of him in the media. Some years ago the name of the road was misspelt as Fazle Haq Road, and it has been changed to A K M Fazlul Haq. What the letter "M" stands for remains a mystery. In memory of Fazlul Haq