Garo people

A Garo couple in traditional dress | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,145,323 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 997,716[1] | |

| Meghalaya | 821,026 |

| Assam | 136,077 |

| Tripura | 12,952 |

| 120,000[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Garo | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Songsarek | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kachari people, Bodo people, Hajong people, Tripuri people, Dimasa people | |

The Garos are an indigenous Tibeto-Burman ethnic group from the Indian subcontinent, notably found in the Indian states of Meghalaya, Assam, Tripura, Nagaland, and neighboring areas of Bangladesh, notably Mymensingh, Netrokona, Jamalpur, Sherpur and Sylhet, who call themselves A·chik Mande (literally "hill people," from a·chik "bite soil" + mande "people") or simply A·chik or Mande.[3] They are the second-largest tribe in Meghalaya after the Khasi and comprise about a third of the local population. The Garos are one of the few remaining matrilineal societies in the world.

Religion

A large part of the Garo community follow Christianity,[4] with some rural pockets following traditional animist religion known as Songsarek and its practices. The book The Garo Tribal Religion: Beliefs And Practices[5] tries to interpret and expound on the origin and migration of the Garos — consisting of tribal groups who settled in the Garo Hills and their ancient animistic religious beliefs and practices: deities who must be appeased with rituals, ceremonies and animal sacrifices to ensure welfare of the tribe.

The Garo tribal religion is popularly known as Songsarek. Their tradition "Dakbewal" relates to their most prominent cultural activities. In 2003 the group called "Rishi Jilma" was founded to safeguard the ancient Garo Songsarek religion. Seeing the Songsarek population in decline, youth from the Dadenggiri subdivision of Garo Hills felt the need to preserve the Songsarek culture. The Rishi Jilma group is active in about 500 villages in and around Garo Hills.

Geographical distribution

The Garos are mainly distributed over the Garo Hills, Khasi Hills, Ri-Bhoi Districts in Meghalaya, Kamrup, Goalpara, Karbi Anglong districts of Assam, Khasi Hills in Meghalaya and Dimapur (Nagaland State), substantial numbers (about 200,000) are found in greater Mymensingh (Tangail, Jamalpur, Sherpore, Netrakona, Mymensingh) and capital Dhaka, Gazipur, Sirajgonj, Rangpur, Sunamganj, Sylhet, Moulovibazar districts of Bangladesh.

It is estimated that total Garo population in India and Bangladesh together is about 1 million.[6]

Garos are also found scattered in the Indian state of Tripura. The recorded Garo population was around 6,000 in 1971.[7] In a recent survey conducted by the newly revived Tripura Garo Union revealed that the number has increased to about 15,000, spreading to all the four districts of Tripura.

Garos form minorities in Cooch Behar, Jalpaiguri, Darjeeling and West Dinajpur of West Bengal, as well as in Nagaland. The present generation of Garos forming minorities in these states of India do not speak the ethnic language any more.

Language

The Garo language belongs to the Tibeto-Burman language family. The language was not traditionally written down; customs, traditions, and beliefs were handed down orally. It is believed that the written language was lost in its transit to the present Garo Hills. Garo language/script was written on the skins of cows; while on the way their ancestors faced famines so they cooked them. The written language/script was lost.

The Garo language has dialects — A·beng or Am·beng, Matabeng, Atong, Me·gam, Matchi, Dual [Matchi-Dual], Ruga, Chibok, Chisak, Gara, Gan·ching [Gara-Gan·ching], A·we etc. In Bangladesh A·beng is the usual dialect written in Bengali script, but A·chik is used more in India. A·we has become the standard dialect of the Garos written in Roman script.[8] A·we is used in Garo literature and, hence, for the translation of the Bible. The Garo language has some similarities with Boro-Kachari, Dimasa, and Kok-Borok languages.

The modern official language in schools and government offices is English.

Historical accounts

According to one oral tradition, the Garos first immigrated to Garo Hills from Tibet (referred to as Tibotgre) around 400 BC under the leadership of Jappa Jalimpa, crossing the Brahmaputra River and tentatively settling in the river valley. The Garos finally settled down in Garo Hills (East-West Garo Hills), finding providence and security in this uncharted territory and claiming it their own. Records of the tribe by invading Mughal armies and by British observers in what is now Bangladesh wrote of the brutality of the people.

The earliest written records about the Garo dates from around 1800. They "...were looked upon as bloodthirsty savages, who inhabited a tract of hills covered with almost impenetrable jungle, the climate of which was considered so deadly as to make it impossible for a white man to live there" (Playfair 1909: 76-77). The Garo had the reputation of being fierce headhunters, the social status of a man being decided by the number of heads he owned.

In December 1872, the British sent battalions to Garo Hills to establish their control in the region. The attack was conducted from three sides – south, east, and west. The Garo warriors (matgriks) confronted them at Rongrenggre with their spears, swords, and shields. The battle that ensued was heavily unmatched, as the Garos did not have guns or mortars like the British Army.

Togan Nengminja, a young matgrik, was in command of the valiant Garo warriors. He fell fighting with unmatched heroism and courage in December 1872.

Later, a Garo patriot and statesman Sonaram R Sangma fought against the British and tried to unify the contiguous Garo inhabited areas.

Culture

The Garos are one of the few remaining matrilineal societies in the world. The individuals take their clan titles from their mothers. Traditionally, the youngest daughter (nokmechik) inherits the property from her mother. Sons leave the parents' house at puberty and are trained in the village bachelor dormitory (nokpante). After getting married, the man lives in his wife's house.

Nokpantes are glory of the past and all children are given equal care, rights and importance by the modern parents.

Garos are only a matrilinear society but not matriarchal. While the property is owned by women, the men govern the society and domestic affairs and manage the property.

The Garo people have traditional names.[9] However, the culture of modern Garo community has been greatly influenced by Christianity.

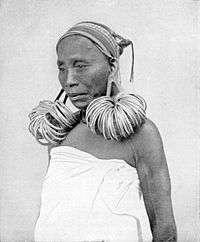

Ornaments: Both men and women enjoy adorning themselves with ornaments:

- Nadongbi or sisa – made of a brass ring worn in the lobe of the ear

- Nadirong – brass ring worn in the upper part of the ear

- Natapsi – string of beads worn in the upper part of the ear

- Jaksan – bangles of different materials and sizes

- Ripok – necklaces made of long barrel-shaped beads of cornelian or red glass while some are made out of brass or silver and are worn in special occasions

- Jaksil – elbow ring worn by rich men on Gana xeremonies

- Penta – small piece of ivory struck into the upper part of the ear projecting upwards parallel to the side of the head

- Seng·ki – waistband consisting of several rows of conch-shells worn by women

- Pilne – head ornament worn during dances only by women

Weapons: Garos have their own weapons. One of the principal weapons is a two-edged sword called mil·am made of one piece of iron from hilt to point. There is a cross-bar between the hilt and the blade where a bunch of ox’s tail-hair is attached. The other types of weapons are shield, spear, bow and arrow, axe, dagger, etc.

Food and drink: The staple cereal food is rice. They also eat millet, maize, tapioca etc. Garos are very liberal in their food habits. They rear goats, pigs, fowls, ducks etc. and relish their meat. They eat other wild animal like deer, bison, wild pigs etc. Fish, prawns, crabs, eels and dry fish are a part of their food. Their jhum fields and the forests provide them with vegetables and roots for their curry. Bamboo shoots are esteemed as a delicacy. They use a kind of potash in curries, which they obtained by burning dry pieces of plantain stems or young bamboo locally known as kalchi or katchi. After they are burnt, the ashes are collected and dipped in water; they are strained in conical shapes in a bamboo strainer. These days most of the townspeople use cooking soda from the market in place of ash water. Besides other drinks, country liquor plays an important role in the life of the Garos.

Garo architecture: Generally one finds similar typea of arts and architecture in Garo Hills. They normally use locally available building materials like timbers, bamboo, cane and thatch. Garo architecture can be classified into following categories:

- Nokmong – The house where every A'chik household can stay together. This house is built so that inside the house there are provisions for sleeping, hearth, sanitary arrangements, kitchen, water storage, place for fermenting wine, place for use as cattle-shed or for stall-feeding the cow, and the space between earthen floor and raised platform for use as pigsty and in the back of the house; the raised platform serves as hencoop for keeping fowl and for storing firewood, thus every need is fully provisioned for in one house.

- Nokpante – In the Garo habitation, the house where unmarried male youth or bachelors live is called Nokpante. The word Nokpante means the house of bachelors. Nokpantes are generally constructed in the front courtyard of the Nokma, the chief. The art of cultivation, arts and cultures, and games are taught in the Nokpante to the boys by the senior boys and elders.

- Jamsireng – In certain areas, in the rice field or orchards, small huts are constructed. They are called Jamsireng or Jamdap. The season’s fruits or grains are collected and stored in the Jamsireng, or it can be used for sleeping.

- Jamadal – The small house, a type of miniature house, built in the jhum fields is called Jamadal or ‘field house’. In certain places, where there is danger from wild animals, a small house with ladder is constructed on the treetop. This is called Borang or ‘house on the treetop’.

Festivals

The common and regular festivals are those connected with agricultural operations.

Most Garo festivals are based on agricultural cycle of crops. The harvesting festival Wangala is the biggest celebration of the tribe happening in the month of October or November every year. It is the thanksgiving after harvest in the honor of the god Saljong, provider of nature's bounties.

Other festivals include Gal·mak Goa, Agalmaka, etc.

Wangala of Asanang

There is a celebration of the 100-drum festival in Asanang near Tura in West Garo Hills, Meghalaya, India usually in October or November. Thousands of people, especially young people, gather at Asanang and celebrate Wangala with great joy. Beautiful Garo girls known as nomil and handsome boys pante take part in 'Wangala' festivals. The pantes beat a kind of long drum called dama in groups and play bamboo flute. The nomils with colorful costumes dance to the tune of dama and folk songs in a circle. Most of the folk songs depict ordinary Garo life, God's blessings, beauty of nature, day-to-day struggles, romance, and human aspirations.

Dhaka Wangala

There are 30,000 Garos living in Dhaka. They celebrate their Wangala festival every year with the new spirit as a thanksgiving to the creator. The Garos started the Dhaka Wangala festival in the capital city in 1994 by the leadership of Fr. Cammillus Rema, a professor of National Major Seminary. There were a Nokma Committee for the celebration. The first Kamal was Fr. Cammilus Rema. The committee included Albert Mankin, Topon Marak, Sanjeeb Drong, Nipun Sangma, Theophil Nokrek, Ranjit Ruga, Torun Marak, Premson Mrong and others. At least 10,000 Garos attended the first Dhaka Wangala. At present Garos celebrates three Wangala in Dhaka (Botomly, Gulshan and Banani). The Nokma of Wangala is elected every year. He is the head of the feast. In 2014 Dhaka Wangala was celebrated at Technical School field of Botomly. The chief guest was Adv. Promode Mankin MP, minister for Social Welfare, People's Republic of Bangladesh. Special guests were Nirmal Rozario, Secretary of Bangladesh Christian Association; and Theophil Nokrek, Ph.D researcher and Director, Caritas Development Institute, Dhaka. More than 15,000 Garos attended. The celebration started with the Wangala mass presided over by Rt. Rev. Bishop Ponen Paul Kubi, csc, Bishop of Mymensingh. The mixed culture Wangala bring together all Garos to one place for worship and thanksgiving to God. The Garos of Bangladesh celebrates Wangala at Abima, Modhupur, Tangail, Durgapur, Netrokona, and Ranikhong as '100 Drums.

The ancient traditional culture of Garos is disappearing in some areas due to lack of practice and nurturing by the society and Government. Some researchers are trying to promote this traditional culture to preserve it in Bangladesh and in India. Rev. Monindronath Marak, Subhash Jengcham, Theophil Nokrek, Sanjeeb Drong, Albert Mankin, Badhon Areng, Babul D' Nokrek, Bashor Dango are trying to research the Garo culture and tradition.

Christmas

Though Christmas is a religious celebration, December is a great season of celebration in Garo Hills. In the first week of December the town of Tura and all other smaller towns are illuminated with lights. This celebration featured by worship, dance, merry-making, grand feasts and social visits goes on till 10 January. People from all religions and sections take part in the Christmas celebration. In December 2003 the tallest Christmas tree of the world was erected at Dobasipara, Tura by the Baptist boys of Dobasipara. Its height was 119.3 feet, covered by BBC and widely broadcast on television. The tree was decorated with 16,319 colored light bulbs; it took about 14 days to complete the decoration.

Ahaia Winter Festival

The annual festival, conceptualised in 2008, is aimed to promote and brand this part of the region as a popular tourist destination by giving an opportunity for the local people to showcase their skills and expertise. The three-day fest features a gala event with carnival, cultural show, food festival, rock concert, wine festival, angling competition, ethnic wear competition, children's fancy dress, DJ Nite, exhibitions, housie housie, and other games. The entry forms for carnival and other events are available at the Tourist Office, Tura.

Music and dance

Group songs may include Ku·dare sala, Hoa ring·a, Injoka, Kore doka, Ajea, Doroa, Nanggorere goserong, Dim dim chong dading chong, Serejing, Boel sala etc.

Dance forms are Ajema Roa, Mi Su·a, Chambil Moa, Do·kru Sua, Chame mikkang nia, Kambe Toa, Gaewang Roa, Napsepgrika and many others.

Traditional Garo musical instruments can broadly be classified into four groups.[10]

- Idiophones: Self-sounding and made of resonant materials – Kakwa, Nanggilsi, Guridomik, Kamaljakmora, all kinds of gongs, Rangkilding, Rangbong, Nogri etc.

- Aerophone: Wind instruments, whose sound come from air vibrating inside a pipe when is blown – Adil, Singga, Sanai, Kal, Bolbijak, Illep or Illip, Olongna, Tarabeng, Imbanggi, Akok or Dakok, Bangsi rori, Tilara or Taragaku, Bangsi mande, Otekra, Wa·pepe or Wa·pek.

- Chordophone: Stringed instrument – Dotrong, Sarenda, Chigring or Bagring, Dimchrang or Kimjim, Gongmima or Gonggina.

- Membranophone: With skins or membranes stretched over a frame – Am·being Dama, Chisak Dama, Atong Dama, Garaganching Dama, Ruga and Chibok Dama, Dual-Matchi Dama, Nagra, Kram etc.

Professions

The Garos rely on nature. Their profession is hunting and warrior known as Matgrik. They practice jhum cultivation which is the most common agricultural tradition. For more than 4,000 years, the Garos have been practicing jhum cultivation. It was their main profession for feeding themselves.

But in the last 50 years the most changing scenario of the Garo ethnic people is the changing of professions. They are now influenced and have adapted to the modern technology and professions. They are engaged in Government and non-government jobs. In India Government jobs are most common for the Garos. They might have jobs in schools, colleges, universities and other educational institutions. In Bangladesh their jobs are more diverse than in India. Almost 30,000 Garos are living in Dhaka metropolitan city and most them are working in beauty parlours, EPZ industries, housekeeping, security personnel, driving, NGOs private service, real-estate, garment industries, etc. There are a good number in Bangladesh Civil Service Cedre service. In Dimapur, Nagaland State, the Garo people may work as day labourers.

Literature

Garo literature mainly transferred from generation to generation and one place to another orally. Most of the oral tradition become the element of Garo literature. One of the oldest book written by Major A. Playfair, The Garos, is a source of information which was published in 1909. Dr. Sinha T.C published a book in 1955 on the Garos: The Psyche of Garos.

References

- ↑ "A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix". censusindia.gov.in. Government of India. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ "Garo". Ethnologue. SIL International. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ Official Homepage of Meghalaya State of India Archived 2008-03-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "People of Meghalaya".

- ↑ Paulinus R. Marak: The Garo tribal religion: beliefs and practices (Delhi: Anshah Pub. House, 2005) ISBN 8183640028

- ↑ 'Garo' in: Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2013. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 17th edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International: 889,000 in India (2001 census), 120,000 in Bangladesh (2005). Population total all countries: 1,009,000.

- ↑ Gan-Chaudhuri, Jagadis. Tripura: The Land and its People. (Delhi: Leeladevi Publications, 1980) p. 10

- ↑ Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati (2013). "The Garo language". The Language Gulper. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Academic study about personal names in Garo villages

- ↑ Culture section in the official Garo Hills area Archived 2006-05-02 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garo people. |

- Official site of Meghalaya State of India

- East Garo Hills District: The people

- West Garo Hills District official website: The people - Garos

- South Garo Hills District official website - People and Culture

- Ethnologue entry for Garo

- Still The Children Are Here (brief documentary of a Garo neighbourhood in Sadolpara, interior Garo Hills)