Khasi people

_Biplob_Rahman.jpg) Khasi men near Moulvibazar, Bangladesh | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,512,831 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,427,711[1] | |

| Meghalaya | 1,411,775[1] |

| Assam | 15,936[1] |

| 85,120 | |

| Languages | |

| Khasi official | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (85%) • Ka Niam Khasi (13%) Islam (2%) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Khmers,Kachins, Palaungs, Was, Kinh,and other Mon–Khmers | |

The Khasi people, endonym: Ki Khun U Hynñiewtrep ("Children of the Seven Huts"), are an indigenous ethnic group of Meghalaya in north-eastern India, with a significant population in the bordering state of Assam, and in certain parts of Bangladesh. The Khasi people are the native people of Meghalaya and are the largest ethnic group in the state. Their language, Khasi, is categorised as the northernmost Austroasiatic language. Primarily an oral language, they had no script of their own, they used the Bengali script until the arrival of the Welsh missionaries. Particularly significant in this regard was a Welsh evangelist, Thomas Jones, who had transcribed the Khasi language into the Roman/Latin script. The Khasi people form the majority of the population of the eastern part of Meghalaya, and is the state's largest community, with around 48% of the population of Meghalaya. Before the arrival of Christian missionaries the Khasi people practiced an indigenous tribal religion.[2][3] Though around 85% of the Khasi populace have embraced Christianity, a substantial minority of the Khasi people still follow and practice their age old indigenous religion, which is known as Ka Niam Khasi. It is essentially a form of Nature worship. The Khasi people also have consecrated forests known as "Law Kyntang" which are evidence of the age-old relation and respect they have always held for Nature. They have sound knowledge of medicinal herbs and plants. Other religions practised among the Khasis include Catholicism, Anglicanism, Unitarianism, Presbyterianism (largest Christian denomination among the Khasis), and others. A small number of Khasis, as a result of inter-community marriages, are also Muslims. The main crops produced by the Khasi people are betel leaf, areca nut, oranges, local rice, vegetables, etc.

The War sub-tribe of the Khasi community designed and built the famous living root bridges of the Cherrapunji region. Under the Constitution of India, the Khasis have been granted the status of Scheduled Tribe. A unique feature of the Khasi people is that they follow the matrilineal system of descent and inheritance. However, it must not be wrongly thought that men are completely powerless and have no say in private affairs of the household whatsoever. In matters of inheritance, some families do give men shares of the ancestral property, though the daughters usually get bigger shares. The reason is that, since women are the ones to continue the family lineage, giving them larger shares is necessary for them to run the households. In the Khasi system of asset management, the Khasi uncles (Kñi) of the household (usually under the authority of the eldest Kñi), are the managers of their sister's property. No decision can be taken without their consent. In their wife's household too, they provide for their children like a normal father would. In present times, many Khasis are well placed in government and corporate sectors. Many Khasis are well educated. The tribe has produced many IAS, IPS and IFS bureaucrats. Many Khasis are also settled abroad, particularly in the USA and Great Britain.

History

Khasi mythology

Khasi mythology traces the tribe's original abode to 'Ki Hynñiewtrep ("The Seven Huts").[4] According to the Khasi mythology, "U Blei Trai Kynrad" (God, the Lord Master) had originally distributed the human race into 16 heavenly families (Khadhynriew Trep).[5] However, seven out of these 16 families are stuck on earth while the other 9 are stuck in Heaven. According to the myth, a heavenly ladder resting on the sacred Lum Sohpetbneng Peak (located in the present-day Ri-Bhoi district)enabled people to go freely and frequently to heaven whenever they pleased until one day they were tricked into cutting a divine tree which was situated at Lum Diengiei Peak (also in present-day Ri-Bhoi district), a grave error which prevented them access to the heavens forever. This myth is often seen as a metaphor of how nature and trees in particular are the manifestation of the divine on Earth and destroying nature and trees means severing our ties with the Divine. The Khasi indigenous religion like many other tribal religions of the world which are all based on nature worship face a growing threat of disappearance with the widespread dominance of Christianity and draws its beliefs from earlier times. Like the Japanese, the Khasis use the Rooster as a symbol because they believe that it was he who aroused God and also humbly paved and cleared the path for God to create the Universe in the beginning of time. The rooster is the symbol of Morning marking a new beginning and a new sunrise.

Scholarly research

The Khasi language is classified as part of the Austroasiatic language family. According to Peter Wilhelm Schmidt, the Khasi people are related to the Mon-Khmer people of South East Asia. Multiple researches indicate that the Austroasiatic populations in India are derived from migrations from southeast Asia during the Holocene. Many of the words also originate from the Tibetan language. "Nga" meaning "I" is the same in Khasi. Meghalaya was a part of Burma much before India claimed it as a part of it after it's independence from British rule. Traces of connections with the Kachin tribe of North Burma have been also been in the Khasis. The Khasi people also have their own word for the Himalayan mountains which is "Ki Lum Makachang" which means that at one point of time, they did cross the mighty mountains. Therefore all these records and their present culture, features and language strongly show that they also have a strong Tibeto-Himalayan- Burman influence. The word "Khas" means hills and they have always been people of cold and hilly regions and have never been connected to the plains or arid regions. This nature loving tribe call the wettest place on Earth their home. The village of Mawsynram in Meghalaya receives 467 inches of rain per year.

Modern times

The Khasis first came in contact with the British in 1823, after the latter captured Assam. The area inhabited by the Khasis became a part of the Assam province after the Khasi Hill States (which numbered to about 25 kingdoms) entered into a subsidiary alliance with the British.

Geographical distribution and sub-groups

According to the 2011 Census of India, over 1.41 million Khasi lived in Meghalaya in the districts of East Khasi Hills, West Khasi Hills, South West Khasi Hills, Ri-Bhoi, West Jaintia Hills and East Jaintia Hills. In Assam, their population reached 35,000. It is generally considered by many Khasi sociologists that the Khasi Tribe consist of seven sub-tribes, hence the title 'Children of the Seven Huts': Khynriam, Pnar, Bhoi, War, Maram, Lyngngam and Diko. The Khynriam (or Nongphlang) inhabit the uplands of the East Khasi Hills District; the Pnar or Synteng live in the uplands of the Jaintia Hills. The Bhoi live in the lower hills to the north and north-east of the Khasi Hills. and Jaintia Hills towards the Brahmaputra valley, a vast area now under Ri Bhoi District. The War, usually divided into War-Jaintia and War-Khynriam in the south of the Khasi Hills, live on the steep southern slopes leading to Bangladesh. The Maram inhabit the uplands of the central parts of West Khasi Hills Districts. The Lyngngam people who inhabit the western parts of the West Khasi Hills bordering the Garo Hills display linguistic and cultural characteristics which show influences from both the Khasis to their east and the Garo people to the west. The last sub-group completing the "seven huts", are the Diko, an extinct group who once inhabited the lowlands of the West Khasi Hills.

Genetics

Khasi people are mostly of short stature, with some exceptions. Estimates show that the average height is 5 feet 2 inches for Khasi men and around 4 feet 11 inches for khasi women. A majority of Khasi people are short while a very few among them are taller, such as some Khasi males with heights ranging from 5.5 feet to 5.6 feet respectively and for women heights ranging from 5 feet to 5.4 feet normally.

Dress

The traditional Khasi male dress is a Jymphong, a longish sleeveless coat without collar, fastened by thongs in front. Nowadays, most male Khasis have adopted western attire. On ceremonial occasions they appear in a Jymphong and sarong with an ornamental waist-band and they may also wear a turban.

The traditional Khasi female dress is called the Jainsem or Dhara, both of which are rather elaborate with several pieces of cloth, giving the body a cylindrical shape. On ceremonial occasions they may wear a crown of silver or gold. A spike or peak is fixed to the back of the crown, corresponding to the feathers worn by the menfolk. The Jainsem consists of two pieces of material fastened at each shoulder. The "Dhara" consists of a single piece of material also fastened at each shoulder.

Marriage

The Khasis are, for the most part, monogamous. Their social organisation does not favour other forms of marriage; therefore, deviation from this norm is quite rare. Young men and women are permitted considerable freedom in the choice of mates. Potential marriage partners are likely to have been acquainted before betrothal. Once a man has selected his desired spouse, he reports his choice to his parents. They then secure the services of a mediator to make the arrangements with the woman's family (provided that the man's clan agree with his choice). The parents of the woman ascertain her wishes and if she agrees to the arrangement her parents check to make certain that the man to be wed is not a member of their clan (since Khasi clans are exogamous, marital partners may not be from the same clan). If this is satisfactory then a wedding date is set.

Divorce (with causes ranging from incompatibility to lack of offspring) is easily obtainable. This ceremony traditionally consists of the husband handing the wife 5 cowries or paisa which the wife then hands back to her husband along with 5 of her own. The husband then throws these away or gives them to a village elder who throws them away. Present-day Khasis divorce through the Indian legal system.

The type of marriage is the determining factor in marital residence. In short, post marital residence for a married man when an heiress (known as Ka Khadduh) is involved must be matrilocal (that is, in his mother-in-law's house) , while post marital residence when a non-heiress is involved is neolocal. Generally, Khasi men prefer to marry a non-heiress because it will allow them to form independent family units somewhat immune to pressures from the wife's kin. Traditionally (though nowadays rule is not absolutely true), a Khasi man returns to his Iing-Kur (maternal home) upon the death of his spouse (if she is a Khadduh and they both have no children). These practices are the result of rules governing inheritance and property ownership. These rules are themselves related to the structure of the Khasi Kur (clan system).

Onomastics

Khasi names are known for their originality and elaborate nature. The given names may be invented by parents for their children, and these can be based on traditional native names, Christian names, or other English words. The family names, which they call "surnames," remain typically in the native Khasi language.

Traditional polity

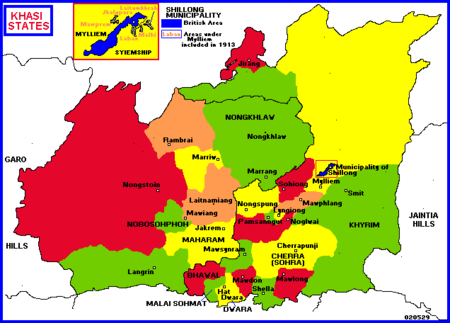

The traditional political structure of the Khasi community is democratic in nature. In the past, the Khasis consisted of independent native states called Syiemships, where male elders of various clans under the leadership of the Chief (called U Syiem) would congregate during Durbars or sessions and come to a decision regarding any dispute or problem that would arise in the Syiemship. At the village level, there exists a similar arrangement where all the residents of the village or town come together under the leadership of an elected Headman (called U Rangbah Shnong), to decide on matters pertaining to the locality. This system of village administration is much like the Panchayati Raj prevalent in most Indian States. There were around 25 independent native states on record which were annexed and acceded to the Indian Union. The Syiems of these native states (called Hima) were traditionally elected by the people or ruling clans of their respective domains. Famous among these Syiemships are Hima Mylliem, Hima Khyrim, Hima Nongkhlaw, amongst others. These Syiemships continue to exist and function till today under the purview of the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council (KHADC), which draws its legal power and authority from the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution of India.[6]

Notable people

- U Tirot Sing Syiem, freedom fighter and martyr

- U Kiang Nangbah, freedom fighter and martyr

- George Gilbert Swell, former Indian Foreign Service officer

- James Michael Lyngdoh, former chief election commissioner of India

- R. Kharlukhi, former member, Central Administrative Tribunal

- Patricia Mukhim, journalist and Padma Shri awardee

- Neil Nongkynrih, director of the Shillong Chamber Choir

- B. Lamare, first Khasi to be appointed judge of a high court

- David R. Syiemlieh, former chairman, Union Public Service Commission

- Kakon Bibi, Bangladeshi freedom fighter, Bir Protik awardee[7][8]

- J.J.M. Nichols Roy or Bah Joy, prominent Khasi preacher and statesman

- U Myllung Soso Tham, Khasi poet

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 "A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix". censusindia.gov.in. Government of India. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ Iarington Kharkongngor (1973), The Preparation For The Gospel In Traditional Khasi Belief. I. Kharkongngor. pp. 19-26.

- ↑ Gurdon, P.R.T. The Khasis.

- ↑ Shakuntala Banaji (1 April 2010). South Asian media cultures. Anthem Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-1-84331-842-2.

- ↑ Aurelius Kyrham Nongkinrih (2002). Khasi society of Meghalaya: a sociological understanding. Indus Publishing. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-81-7387-137-5.

- ↑ "Traditional Institutions of the People of Meghalaya, Heritage of Meghalaya: Department of Arts and Culture, Government of Meghalaya". megartsculture.gov.in. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- ↑ "Bir Protik Kakon Bibi dies". Risingbd.com. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Bangladesh War Liberation hero Bir Protik Kakon Bibi dies". Retrieved 22 March 2018.

Sources

- Chaubey; et al. (2011), "Population Genetic Structure in Indian Austroasiatic Speakers: The Role of Landscape Barriers and Sex-Specific Admixture", Mol Biol Evol, 28: 1013–1024, doi:10.1093/molbev/msq288, PMC 3355372, PMID 20978040

- van Driem, George L. (2007b), Austroasiatic phylogeny and the Austroasiatic homeland in light of recent population genetic studies (PDF)

- Ness, Immanuel (2014), The Global Prehistory of Human Migration, The Global Prehistory of Human Migration

- Zhang; et al. (2015), "Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro-Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent", Scientific Reports, 5: 15486, doi:10.1038/srep15486

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khasi people. |

- Census of India 2001, Scheduled Tribes

- The Khasis by Gurdon, P. R. T.

- Government of Meghalaya Portal

- Dictionary German Khasi