Pilaf

|

Karnataka vegetarian pilaf (or "pulāka" as mentioned in Yājñavalkya Smṛti in Sanskrit) with raita from India. | |

| Alternative names | Pela, Pilav, Pallao, Pilau, Pulao, Pulaav, Palaw, Palavu, Plov, Palov, Polov, Polo, Polu, Kurysh, Fulao, Fulab, Fulav |

|---|---|

| Course | Main |

| Region or state | Indian subcontinent, Central Asia, Balkans, Middle East, East Africa, Caribbean |

| Serving temperature | Hot |

| Main ingredients | Rice, spices, meat or fish, vegetables, dried fruits |

Pilaf or pilau is a dish, originating from the Indian subcontinent,[1] in which rice is cooked in a seasoned broth.[2] In some cases, the rice may attain its brown or golden color by first being sauteed lightly in oil before the addition of broth. Cooked onion, garlic cloves, sliced carrot, other vegetables, as well as a mix of spices, may be added. Depending on the local cuisine, it may additionally contain meat, fish, vegetables, pasta (orzo), or dried fruit. It is also sometimes called rice pilaf.

Believed to have originated in ancient India and spread from there to ancient Iran,[3] pilaf and similar dishes are common to Balkan, Middle Eastern, Eastern Europe, South Caucasian, Central and South Asian, East African, Latin American, and Caribbean cuisines. It is a staple food and a popular dish in Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Israel,[4] Crete, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Romania, Russia, Kurdistan, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Pakistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Zanzibar, Uganda, Tajikstan,[5] Turkey,[6] Turkmenistan, Xinjiang, and Uzbekistan.[7][8]

Etymology

The English spelling is influenced by the Modern Greek piláfi (πιλάφι), which comes from the Turkish pilav,[9] which in turn comes from Persian polow (پلو), Hindi: pulāo, from Sanskrit pulāka (meaning "a ball of rice"), which in turn, is probably of Dravidian origin.[10] A Spanish dish, paella, traditionally a communal meal made from rice and fish, shellfish, rabbit or chicken, cooked in a large pan, has similarities in recipe and methodology, but derives from a Valencian word, out of the Old French word paelle for "pan" (Latin: patella).

History

The ancient Hindu text Mahabharata from the Indian subcontinent, mentions rice and meat cooked together, and the word "pulao" or "pallao" is used to refer to the dish in ancient Sanskrit works such as the Yājñavalkya Smṛti.[1][11]

Pilaf was known to have been served to Alexander the Great at a royal banquet following his capture of the Sogdian capital of Marakanda (modern Samarkand).

The first known recipe for pilaf is by the tenth-century Persian scholar Avicenna, who in his books on medical sciences dedicated a whole section to preparing various dishes, including several types of pilaf. In doing so, he described advantages and disadvantages of every item used for preparing the dish. Accordingly, Persians consider Ibn Sina to be the "father" of modern pilaf.

Pilau became standard fare in the Middle East and Transcaucasia over the years with variations and innovations by the Persians, Arabs, Turks, and Armenians. It was introduced to Israel by Bukharan and Persian Jews.

During the period of the Soviet Union, the Central Asian versions of the dish spread throughout all Soviet republics, becoming a part of the common Soviet cuisine.

Local varieties

Afghanistan

In Afghan cuisine, Kabuli palaw or qabili palaw (Dari : قابلی پلو ) is made by cooking basmati with mutton, lamb, beef or chicken, and oil. Kabuli Palaw is cooked in large shallow and thick dishes. Fried sliced carrots and raisins are added. Chopped nuts like pistachios, walnuts, or almonds may be added as well. The meat is covered by the rice or buried in the middle of the dish. The Kabuli Palaw rice with carrots and raisins is very popular in Saudi Arabia, where it is known as roz Bukhari (Arabic: رز بخاري), meaning Bukharan rice.

Armenia

Armenians use a lot of bulgur (cracked wheat) in their pilav dishes.[12] Lapa is an Armenian word with several meanings one of which is a "watery boiled rice, thick rice soup, mush" and lepe which refers to various rice dishes differing by region.[13] Antranig Azhderian describes Armenian pilav as "dish resembling porridge".[14]

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijani cuisine includes more than 40 different plov recipes.[15] One of the most reputed dishes is plov from saffron-covered rice, served with various herbs and greens, a combination distinctive from Uzbek plovs. Traditional Azerbaijani plov consists of three distinct components, served simultaneously but on separate platters: rice (warm, never hot), gara (fried meat, dried fruits, eggs, or fish prepared as an accompaniment to rice), and aromatic herbs. Rice is not mixed with the other components even when eating plov.[16]

- Rice pilaf examples from Azerbaijan

- Azerbaijani shah-pilaf.

Brazil

A significantly modified version of the recipe, often seen as influenced by what is called arroz pilau there, is known in Brazil as arroz de frango desfiado or incorrectly risoto de frango (Portuguese: [aˈʁoʒ dʒi ˈfɾɐ̃gu dʒisfiˈadu], "shredded chicken rice", [ʁiˈzotu], "chicken risotto"). Rice lightly fried (and optionally seasoned), salted and cooked until soft (but neither soupy nor sticky) in either water or chicken stock is added to chicken stock, onions and sometimes cubed bell peppers (cooked in the stock), shredded chicken breast, green peas, tomato sauce, shoyu, and optionally vegetables (e.g. canned sweet corn, cooked carrot cubes, courgette cubes, broccolini flowers, chopped broccoli or broccolini stalks/leaves fried in garlic seasoning) and/or herbs (e.g. mint, like in canja) to form a distantly risotto-like dish – but it is generally fluffy (depending on the texture of the rice being added), as generally, once all ingredients are mixed, it is not left to cook longer than 5 minutes. In the case shredded chicken breast is not added, with the rice being instead served alongside chicken and sauce suprême, it is known as arroz suprême de frango (Portuguese: [ɐˈʁo s(ː)uˈpɾẽm(i) dʒi ˈfɾɐ̃gu], "chicken supreme rice").

Caribbean

In the Eastern Caribbean and other Caribbean territories there are variations of pelau which include a wide range of ingredients such as pigeon peas, green peas, string beans, corn, carrots, pumpkin, and meat such as beef or chicken, or cured pig tail. The seasoned meat is usually cooked in a stew, with the rice and other vegetables added afterwards. Coconut milk and spices are also key additions in some islands.

Central Asia

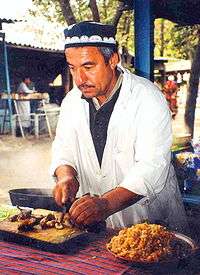

Central Asian, e.g. Tajik and Uzbek plov (Tajik: палав, Uzbek: palov) or osh differs from other preparations in that rice is not steamed, but instead simmered in a rich stew of meat and vegetables called zirvak, until all the liquid is absorbed into the rice. A limited degree of steaming is commonly achieved by covering the pot. It is usually cooked in a kazan (or deghi) over an open fire. The cooking tradition includes many regional and occasional variations.[7][17] Commonly, it is prepared with lamb, browned in lamb fat or oil, and then stewed with fried onions, garlic and carrots. Chicken plov is rare but found in traditional recipes originating in Bukhara. Plov is usually spiced with whole black cumin, coriander, barberries, red pepper, marigold, and pepper. Heads of garlic and garbanzo beans are buried into the rice during cooking. Sweet variations with dried apricots, cranberries and raisins are prepared on special occasions.

Although often prepared at home for family and guests by the head of household or the housewife, plov is made on special occasions by the oshpaz (osh master chef), who cooks the national dish over an open flame, sometimes serving up to 1,000 people from a single cauldron on holidays or occasions such as weddings. Oshi nahor, or "morning plov", is served in the early morning (between 6 and 9 am) to large gatherings of guests, typically as part of an ongoing wedding celebration.

The Uzbek-style plov cooking recipes are spread nowadays throughout all post-Soviet countries and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China.

Greece

In the Greek cuisine, piláfi (πιλάφι) is the fluffy and soft, but neither soupy nor sticky, rice that has been boiled in a meat stock or bouillon broth. In Northern Greece, it is considered poor form to prepare piláfi on a stovetop; the pot is properly placed in the oven. Gamopílafo ("wedding pilaf") is the prized pilaf served traditionally at weddings and major celebrations in Crete: rice is boiled in lamb or goat broth, then finished with lemon juice. Gamopílafo though it bears the name is not a pilaf but rather a kind of risotto, with creamy and not fluffy texture.

India

Known as pulao, polao, pallao and pulav locally, the rice dish has been an integral part of Indian cuisine since the ancient era. The Mahabharata mentions rice and meat cooked together, and the word pulāka is used to refer to the dish in Sanskrit works such as the Yājñavalkya Smṛti.[1][11] A pulao is a dish consisting of rice and a mixture of either lentils or vegetables, mainly including peas, potatoes, french beans, carrots or meat, mainly chicken, fish, lamb, pork or prawn. It is usually served on special occasions and weddings, though it is not uncommon to eat it for a regular lunch or dinner meal. It is considered very high in food energy and fat. A pulao is often complemented with either spiced yogurt or raita.

- Rice pilaf examples from India

- Bengali pulao, India

Soya Pulao, India

Soya Pulao, India Vegetarian pulao, India

Vegetarian pulao, India

Iran

Persian culinary terms referring to rice preparation are numerous and have found their way into the neighbouring languages: polo (rice cooked in broth while the grains remain separate, straining the half cooked rice before adding the broth and then "brewing"), chelo (white rice with separate grains), kateh (sticky rice) and tajine (slow cooked rice, vegetables, and meat cooked in a specially designed dish also called a tajine). There are also varieties of different rice dishes with vegetables and herbs which are very popular among Iranians.

There are four primary methods of cooking rice in Iran:

- Chelo: rice that is carefully prepared through soaking and parboiling, at which point the water is drained and the rice is steamed. This method results in an exceptionally fluffy rice with the grains separated and not sticky; it also results in a golden rice crust at the bottom of the pot called tahdig (literally "bottom of the pot").

- Polo: rice that is cooked exactly the same as chelo, with the exception that after draining the rice, other ingredients are layered with the rice, and they are then steamed together.

- Kateh: rice that is boiled until the water is absorbed. This is the traditional dish of Northern Iran.

- Damy: cooked almost the same as kateh, except that the heat is reduced just before boiling and a towel is placed between the lid and the pot to prevent steam from escaping. Damy literally means "simmered".

Pakistan

In Pakistan, Pulao (پلاؤ) is a popular dish cooked with Basmati rice and meat (chicken or mutton or beef). Pulao is a rice dish, cooked in seasoned broth with rice, meat and spices. A pulao is often complimented with raita. The rice is made in mutton or beef or chicken stock and an array of spices including: coriander seeds, cumin, cardamom, cloves and others. Mutton and beef have, with time, been replaced with chicken due to higher prices of mutton.[18] The Sindhi pulao (Sindhi: سنڌي پُلاءُ) in the province of Sindh, prepared with mutton or beef or chicken. It is prepared by Sindhi people of Pakistan in their marriage ceremonies, condolence meetings, and other occasions.[19][20]

Palestine and Syria

Traditional Levantine cooking includes a variety of Pilaf known as "Maqlubeh", known across the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean. The rice pilaf which is traditionally cooked with meats, eggplants, tomatoes, potatoes, and cauliflower also has a fish variety known as "Sayyadiyeh", or the Fishermen's Dish.

Turkey

Turkish cousine contains many different pilav types and is the inspiration behind most of the variations in Armenia, Balkans, Greece, and Arab countries due to their past under Ottoman empire rule. Some of these variations are pirinc (rice) pilav, bulgur pilav, and arpa şehriye (orzo) pilav. Using manily these three types, Turkish people make many dishes such as perdeli pilav, and etli pilav (rice cooked with cubed beef). Unlike Chinese rice, if Turkish rice is sticky it is considered unsuccessful. To make the best rice according to Turkish people, one must rinse the rice, cook in butter, then add the water and let it sit until it soaks all the water. This results in a pilav that is not sticky and every single rice grain falls off of the spoon separately.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 K. T. Achaya (1994). Indian food: a historical companion. Oxford University Press. p. 11.

- ↑ "Rice Pilaf". Accessed May 2010.

- ↑ K. T. Achaya (1994). Indian food: a historical companion. Oxford University Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Gil Marks. Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010. ISBN 9780544186316

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish. World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish, 2006, p. 662. ISBN 9780761475712

- ↑ Navy Bean Stew And Rice Is Turkey's National Dish turkishfood.about.com

- 1 2 Bruce Kraig, Colleen Taylor Sen. Street Food Around the World: An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. ABC-CLIO, 2013, p. 384. ISBN 9781598849554

- ↑ Russell Zanca. Life in a Muslim Uzbek Village: Cotton Farming After Communism CSCA. Cengage Learning, 2010, p. 92–96. ISBN 9780495092810

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Pilaf". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, 2006 s.v. 'pilau'

- 1 2 Priti Narain (14 October 2000). The Essential Delhi Cookbook. Penguin Books Limited. p. 116. ISBN 978-93-5118-114-9.

- ↑ Davidson, Alan (2006). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280681-9. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- ↑ Dankoff, Robert (1995). Armenian Loanwords in Turkish. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-447-03640-5.

- ↑ Azhderian, Antranig (1898). The Turk and the Land of Haig; Or, Turkey and Armenia: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque. Mershon Company. p. 171-172.

- ↑ Азербайджанская кухня Archived 2009-02-16 at the Wayback Machine., (Azerbaijani Cuisine, Ishyg Publ. House, Baku (in Russian))

- ↑ Interview with Jabar Mamedov Archived 2008-12-21 at the Wayback Machine., Head Chef at the "Shirvan Shah" Azerbaijani restaurant in Kiev, 31 January 2005.

- ↑ "Uzbek Cuisine Photos: Pilaf". Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ↑ How mutton pulao survived the chicken takeover in Pakistan

- ↑ Reejhsinghani, Aroona (2004). Essential Sindhi Cookbook. Penguin Books India. p. 237. ISBN 9780143032014. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ↑ Reejhsinghani, Aroona. The Sindhi Kitchen. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

External links