Tribes of Albania

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Albania |

|---|

|

|

Mythology and folklore |

|

Festivals |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Monuments |

|

|

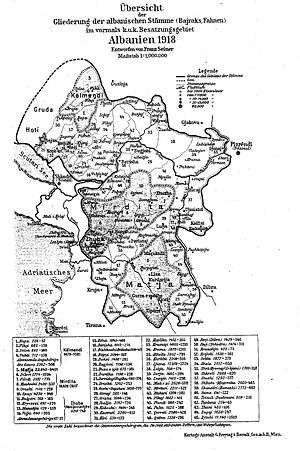

The following is a list of tribes of Albania, a region in south-west Balkans.

Northern Albania

The fact that the tribes of northern Albania were not completely subdued by the Ottomans is raised on the level of orthodoxy among the members of tribes. A possible explanation is that Ottomans did not have any reason to subdue northern Albanian tribes because they needed them as a stable source of mercenaries. The Ottomans implemented baryaktar system within northern Albanian tribes and granted some privileges to the baryaktars (banner chieftans) in exchange for their obligation to mobilize local fighters to support military actions of the Ottoman forces.[1]

In period without stable state control the tribe trialed its members. The usual punishments were, fine, exile or disarmament. The house of the exiled member of the tribe would be burned. In Albania the disarmament was regarded as the most embarrassing verdict.[2]

Members of the tribes of northern Albania believe their history is based on the notions of resistance and isolationism.[3] Some scholars connect this belief with the concept of "negotiated peripherality". Throughout history the territory northern Albanian tribes occupy has been contested and peripheral so northern Albanian tribes often exploited their position and negotiated their peripherality in profitable ways. This peripheral position also affected their national program which significance and challenges are different from those in southern Albania.[4] Such peripheral territories are zones of dynamic culture creation where it is possible to create and manipulate regional and national histories to the advantage of certain individuals and groups.[5]

Northern Albanian tribes have the tradition of Besa, usually translated as "faith", that means "to keep the promise" and "word of honor", which origin can be traced to the Kanun attributed to Lekë Dukagjini, a collection of Albanian traditional customs and cultural practices. Besa is an important part of personal and familial standing and is often used as an example of "Albanianism". Someone who breaks his besa may even be banished from his community.

Organisation

Among Gheg Malësors (highlanders) the fis (clan), was headed by the oldest male and formed the basic unit of tribal society.[6] A political and territorial equivalent consisting of several clans was the bajrak (standard, banner).[6] The leader of a bajrak, whose position was hereditary, was referred to as bajraktar (standard bearer).[6] Several bajraks composed a tribe, which was led by a man from a notable family, while major issues were decided by the tribe assembly whose members were male members of the tribe.[7][6] The Ottomans implemented the bayraktar system within northern Albanian tribes, and granted some privileges to the bayraktars (banner chieftains) in exchange for their obligation to mobilize local fighters to support military actions of the Ottoman forces.[1][8] Those privileges also entailed Albanian tribesmen to pay no taxes and were excluded from military conscription in return for military service as irregular troops however few served in that capacity.[8] Malisors viewed Ottoman officials as a threat to their tribal way of living and left it to their bajraktars to deal with the Ottoman political system.[9] Officials of the late Ottoman period noted that Malisors preferred their children learn use of a weapon and refused to send them to government schools that taught Turkish which were viewed as forms of state control.[10] Most Albanian Malisors were illiterate.[9]

Culture

Autonomy, Kanun and Gjakmarja

Malisor society used tribal law and participated in the custom of bloodfeuding.[11] Ottoman control mainly existed in the few urban centres and valleys of northern Albania and was minimal to almost non-existent in the mountains, where Malisors lived an autonomous existence according to kanun (tribal law) of Lek Dukagjini.[12] At the same time Western Kosovo was also an area were Ottoman rule among highlanders was minimal to non-existent and government officials would ally themselves with local power holders to exert any form of authority.[13] Western Kosovo was dominated by the Albanian tribal system where Kosovar Malisors settled disputes among themselves through their mountain law.[13]

The Law of Lek Dukagjini (kanun) was named after a medieval prince Lekë Dukagjini of the fifteenth century who ruled in northern Albania and codified the customary laws of the highlands.[9] Albanian tribes from the Dibra region governed themselves according to the Law of Skanderbeg (kanun), named after a fifteenth century warrior who fought the Ottomans.[14] Disputes would be solved through tribal law within the framework of vendetta or blood feuding and the activity was widespread among the Malisors.[15] In situations of murder tribal law stipulated the principle of koka për kokë (head for a head) where relatives of the victim are obliged to seek gjakmarje (blood vengeance).[9] Nineteen percent of male deaths in İşkodra vilayet and 600 fatalities per year in Western Kosovo were from murders caused by vendetta and blood feuding during the late Ottoman period.[16]

Besa

Besa is a word in the Albanian language meaning "pledge of honour.[17] The besa was an important institution within the tribal society of the Albanian Malisors.[14] Albanian tribes swore oaths to jointly fight against the government and in this aspect the besa served to uphold tribal autonomy.[14] The besa was used toward regulating tribal affairs between and within the Albanian tribes.[14] The Ottoman government used the besa as a way to co-opt Albanian tribes in supporting state policies or to seal agreements.[14]

During the Ottoman period, the besa would be cited in government reports regarding Albanian unrest, especially in relation to the tribes.[18] The besa formed a central place within Albanian society in relation to generating military and political power.[19] Besas held Albanians together, united them and would wane when the will to enforce them dissipated.[20] In times of revolt against the Ottomans by Albanians, the besa functioned as a link among different groups and tribes.[20]

Geography

The Malisors lived in three geographical regions within northern Albania.[21] Malësia e Madhe (great highlands) contained five large tribes with four (Hoti, Kelmendi, Shkreli, Kastrati) having a Catholic majority and Muslim minority with Gruda evenly split between both religions.[21] Within Malësia e Madhe there were an additional seven small tribes.[21] During times of war and mobilisation of troops, the bajraktar (chieftain) of Hoti was recognised by the Ottoman government as leader of all forces of the Malësia e Madhe tribes having collectively some 6,200 rifles.[21]

Malësia e Vogël (small highlands) with seven Catholic tribes such as the Shala with 4 bajaraktars, Shoshi, Toplana and Nikaj containing some 1,250 households with a collective strength of 2,500 men that could be mobilised for war.[21] Shoshi had a distinction in the region of possessing a legendary rock associated with Lekë Dukagjini.[21]

The Mirdita region which was also a large powerful devoutly Catholic tribe with 2,500 households and five bajraktars that could mobilize 5,000 irregular troops.[21] A general assembly of the Mirdita met often in Orosh to deliberate on important issues relating to the tribe.[21] The position of hereditary prince of the tribe with the title Prenk Pasha (Prince Lord) was held by the Gjonmarkaj family.[21] Apart from the princely family the Franciscan Abbot held some influence among the Mirdita tribesmen.[21]

The government estimated the military strength of Malisors in İşkodra sanjak as numbering over 30,000 tribesmen and Ottoman officials were of the view that the highlanders could defeat Montenegro on their own with limited state assistance.[22]

In Western Kosovo, the Gjakovë highlands contained eight tribes that were mainly Muslim and in the Luma area near Prizren there were five tribes, mostly Muslim.[13] Other important tribal groupings further south include the highlanders of the Dibra region known as the "Tigers of Dibra".[23]

Among the many religiously mixed Catholic-Muslim tribes and one Muslim-Orthodox clan, Ottoman officials noted that tribal loyalties superseded religious affiliations.[21] In Catholic households there were instances of Christians who possessed four wives, marrying the first spouse in a church and the other three in the presence of an imam, while among Muslim households the Islamic tradition of circumcision was ignored.[21]

History

Late Ottoman period

During the Great Eastern Crisis, Prenk Bib Doda, hereditary chieftain of Mirdita initiated a rebellion in mid-April 1877 against government control and the Ottoman Empire sent troops to put it down.[24] Montenegro attempted to gain support from among the Malisors even though it lacked religious or ethnic links with the Albanian tribesmen.[25] Amidst the Eastern Crisis and subsequent border negotiations Italy suggested in April 1880 for the Ottoman Empire to give Montenegro the Tuz district containing mainly Catholic Gruda and Hoti populations which would have left the tribes split between both countries.[26] With Hoti this would have left an additional problem of tensions and instability due to the tribe having precedence by tradition over the other four tribes during peace and war.[26] The tribes affected by the negotiations swore a besa (pledge) to resist any reduction of their lands and sent telegrams to surrounding regions for military assistance.[26]

During the late Ottoman period Ghegs often lacked education and integration within the Ottoman system, while they had autonomy and military capabilities.[15] Those factors gave the area of Gegënia an importance within the empire that differed from Toskëria.[15] Still many Ottoman officers thought that Ghegs, in particular the highlanders were often a liability instead of an asset for the state being commonly referred to as "wild" (Turkish: vahşi) or a backward people that lived in poverty and ignorance for 500 years being hostile to civilisation and progress.[27] In areas of Albania were Malisors lived, the empire only posted Ottoman officers who had prior experience of service in other tribal regions of the state like Kurdistan or Yemen that could bridge cultural divides with Gheg tribesmen.[28]

Sultan Abdul Hamid II, Ottoman officials posted to Albanian populated lands and some Albanians strongly disproved of blood feuding viewing it as inhumane, uncivilised and an unnecessary waste of life that created social disruption, lawlessness and economic dislocation.[29] To resolve disputes and clamp down on the practice the Ottoman state addressed the problem directly by sending Blood Feud Reconciliation Commissions (musalaha-ı dem komisyonları) that produced results with limited success.[18] In the late Ottoman period, due to the influence of Catholic Franciscan priests some changes to blood feuding practices occurred among Albanian highlanders such as guilt being restricted to the offender or their household and even one tribe accepting the razing of the offender's home as compensation for the offense.[18] Ottoman officials were of the view that violence committed by Malisors in the 1880s-1890s was of a tribal nature not related to nationalism or religion.[11] They also noted that Albanian tribesmen who identified with Islam did so in name only and lacked knowledge of the religion.[30]

In the aftermath of the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 the new Young Turk government established the Commissions for the Reconciliation of Blood Feuds that focused on the regions such as İpek (Pejë) and Prizren.[31] The commissions sentenced Albanians who had participated in blood feud killing and the Council of Ministers allowed them to continue their work in the provinces until May 1909.[31] After the Young Turk Revolution and subsequent restoration of the Ottoman constitution, the Hoti, Shala, Shoshi and Kastati tribes made a besa (pledge) to support the document and to stop blood feuding with other tribes until November 6 1908.[32] The Albanian tribes showing sentiments of enthusiasm however had little knowledge of what the constitution would do for them.[33]

During the Albanian revolt of 1910, Malisors such as the Shala tribe fought against Ottoman troops that were sent to quell the uprising, disarm the population by collecting guns, and replace the Law of Lek with state courts and laws.[34] Malisors instead planned further resistance and Albanian tribes living near the border fled into Montenegro while negotiating terms with the Ottomans for their return.[34] The Ottoman commander Mahmud Shevket involved in military operations concluded that the bajraktars had become Albanian nationalists and posed a danger to the empire when compared to previous uprisings.[35]

The Albanian revolt of 1911 was begun during March by Catholic Albanian tribesmen after they returned from exile in Montenegro.[36] The Ottoman government sent 8,000 troops to quell the uprising and ordered that tribal chieftains would need to stand trial for leading the rebellion.[36] During the revolt, Terenzio Tocci, an Italo-Albanian lawyer gathered the Mirditë chieftains on 26/27 April 1911 in Orosh and proclaimed the independence of Albania, raised the flag of Albania and declared a provisional government.[37] After Ottoman troops entered the area to put down the rebellion, Tocci fled the empire abandoning his activities.[37] On 23 June 1911 Albanian Malisors and other revolutionaries gathered in Montenegro and drafted the Greçë Memorandum demanding Albanian sociopolitical and linguistic rights with signatories being from the Hoti, Gruda, Shkreli, Kelmendi and Kastrati tribes.[36] In later negotiations with the Ottomans, an amnesty was granted to the tribesmen with promises by the government to build roads and schools in tribal areas, pay wages of teachers, limit military service to the Istanbul and Shkodër areas, right to carry weapons in the countryside but not in urban areas, the appointment of bajraktars relatives to certain administrative positions and compensate Malisors with money and food arriving back from Montenegro.[36] The final agreement was signed in Podgorica by both the Ottomans and Malisors during August 1912 and the highlanders had managed to thwart the centralist tendencies of the Young Turk government in relation to their interests.[36]

Independent Albania

The last tribal system of Europe located in northern Albania stayed intact until 1944 when Albanian communists seized power and ruled the country for half a century.[38] During that time the tribal system was weakened and eradicated by the communists.[38] After the collapse of communism in the early 1990s, northern Albania underwent demographic changes in areas associated with the tribes becoming in many instances depopulated.[39] Much of the population seeking a better life has moved either abroad or to Albanian cities such as Tiranë, Durrës or Shkodër and populations historically stemming from the tribes have become scattered.[39] Locals that remained in northern Albanian areas associated with the tribes have maintained an awareness of their tribal identity.[39] Like with all Albanians from these regions that awareness however is only in the context of knowing the origins of their families and similar to people in Northern America who today are aware of their ancestral origin (i.e Korean, Swedish, Italian and so on).[39]

Other

Some authors[40] and scholars, including Jovan Cvijić and some other members of the Serbian Academy, asserted that tribes of northern Albania are of Albanian-Serb origin.[41][42][43] The Slavist scholar Konstantin Jireček asserts that there are traditional beliefs that support this idea, that in the "heart of Albania" there are the last remnants of a Slavic population who believe that certain Northern Albanian tribes are of mixed "Albano-Serb" origin[44], while Jovan Cvijić and other Serbian scholars have asserted that in fact the entire Northern Gheg division of the Albanian people are Serbian in origin.[43][45] According to some of these sources, many tribes of Northern Albania (such as Hoti, Nikaj, Kastrati, Kelmend, Shkreli and part of Gruda) have origin in (descend from) a region where the population today speaks Slavic[46] (Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia). An Albanian antithesis asserts that many Serbs and all Montenegrins, Bosniaks and Dalmatians are in fact descendants of Slavicized Albanian tribes.[45]

Tribal regions

Malësia e Madhe

The tribes of Malësia e Madhe, in the Northern Albanian Alps, include ten tribes.[47] These are commonly called "highlanders" (Albanian: malësorët).

Pulat

There are five tribes of the Pulat region.[58]

Dukagjin

There are six tribes of the Dukagjin region.[64]

Another division is that of the Dukagjin highlands, in which Shala, Shoshi, Kiri, Xhani, Plani and Toplana are included.[71]

Gjakova highlands

There are five tribes of the Gjakova highlands (Albanian: Malësia e Gjakovës).[72]

- Nikaj[73] (commonly grouped as Nikaj-Mërtur)

- Mërturi[74] (commonly grouped as Nikaj-Mërtur)

- Krasniqja[75] or Krasniqi[76]

- Gashi[77]

- Bytyçi[78]

Puka

The "seven tribes of Puka" (Albanian: shtatë bajrakët e Pukës), inhabit the Puka region.[79] Durham said of them: "Puka group ... sometimes reckoned a large tribe of seven bairaks. Sometimes as a group of tribes".[80]

Mirdita

- Skana

- Dibrri

- Fani

- Kushneni

- Oroshi

- Spaqi

- Kthella

- Selita

Lezha Highlands

- Bulgëri

- Kryezezi

- Manatia

- Vela

Kruja Highlands

- Kurbini

- Ranza

- Benda

Mat region

- Bushkashi

- Mati

Upper Drin basin

References

- 1 2 Helaine Silverman (1 January 2011). Contested Cultural Heritage: Religion, Nationalism, Erasure, and Exclusion in a Global World. Springer. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4419-7305-4. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Balkanika. Srpska Akademija Nauka i Umetnosti, Balkanolos̆ki Institut. 2004. p. 252. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

...новчана глоба и изгон из племена (у северној Албанији редовно је паљена кућа изгоњеном члану племена). У Албанији се најсрамотнијом казном сматрало одузимање оружја.

- ↑ Helaine Silverman (1 January 2011). Contested Cultural Heritage: Religion, Nationalism, Erasure, and Exclusion in a Global World. Springer. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4419-7305-4. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

... northern Albanians' belief about their own history, based on notions of isolationism and resistance.

- ↑ Helaine Silverman (1 January 2011). Contested Cultural Heritage: Religion, Nationalism, Erasure, and Exclusion in a Global World. Springer. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4419-7305-4. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

... "negotiated peripherality"... the idea that people living in peripheral regions exploit their... position in important, often profitable ways... The implications and challenges of their national program.... in the Albanian Alps .. are very different from those that obtain in the south

- ↑ Helaine Silverman (1 January 2011). Contested Cultural Heritage: Religion, Nationalism, Erasure, and Exclusion in a Global World. Springer. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4419-7305-4. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

Most scholars of frontier life ...to be zones of active cultural creation. .. individuals and groups are in unique position to actively create and manipulate regional and national histories to their own advantage, ...

- 1 2 3 4 Gawrych 2006, pp. 30-31.

- ↑ Barbara Jelavich (29 July 1983). History of the Balkans:. Cambridge University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-521-27458-6. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, pp. 30, 34, 119.

- 1 2 3 4 Gawrych 2006, p. 30.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 120-122.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 121.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 29-30, 113.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, pp. 34-35.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gawrych 2006, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, p. 29.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 1, 9.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 119-120.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 120.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gawrych 2006, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 40.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, p. 62.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 29, 120, 138.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 113.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 29, 118-121, 138, 209.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 122.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 161.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 159.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 160.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 178.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 179.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gawrych 2006, pp. 186-187.

- 1 2 Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 186. ISBN 9781845112875.

- 1 2 Elsie 2015, pp. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Elsie 2015, pp. 11.

- ↑ Edith Durham (1987). High Albania. LO Beacon Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8070-7035-2. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

As for the very large population that must have been of mixed Serbo-Illyrian blood...

- ↑ Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A legal geography of Yugoslavia's disintegration. Oxford Univ Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

Jovan Cvijić... asserts that tribes of northern Albania are of mixed Albanian-Serb origin...

- ↑ Julie Mertus (1999). Kosovo: How Myths and Truths Started a War. University of California Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-520-21865-9. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- 1 2 The South Slav Journal. Dositey Obradovich Circle. 2006. p. 84. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

...a claim by Serbian academicians that all Ghegs were actually Albanized Serbs

- ↑ Isaiah Bowman; G. M. Wrigley (1918). Geographical Review. American Geographical Society. p. 350. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

At the time of the reign of the House of Anjou (1250-1350) there was still a Slav population in the coastal plains and around the Drin river. This population, according to the studies of K. Jireček, was considerably reinforced by settlers from Serbia during the Serbian rule, particularly during the fourteenth century. In the heart of Albania According to their traditions the tribes of northern Albania are of mixed origin, Albano-Serb. They consider themselves related to the Serbian tribes of Montenegro.

- 1 2 Geert-Hinrich Ahrens (6 March 2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-8018-8557-0. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

There are some imaginative theories, such as the Arnautaš theory held by some Serbs, according to which the whole northern Albanian tribe, the Gegs, are actually Albanized Serbs. An Albanian antithesis exists, which says that Montenegrins, Bošniaks, Dalmatians, but also parts of the Serb nation, are Slavicized Albanians.

- ↑ Glasnik Zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini. Zemaljska štamparija. 1911. p. 374. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

Племена Хоти, Никај, Шкрели, Клементи, Кастрати, и један дио племена Груда потјечу из краја гдје се данас говори словјенски

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 15–98.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 15–35.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 36–46.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 47–57.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 58–67.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 68–78.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 81–88.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 93–98.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 99–114.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 99–101.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 102–104.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 107–109.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 110–114.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 115–148.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 115–127.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 128–131.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 132–137.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, p. 138.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 138–142.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 143–148.

- ↑ Enke, Ferdinand (1955). Zeitschrift für vergleichende Rechtswissenschaft: einschliesslich der ethnologischen Rechtsforschung (in German). 58. Germany: Akademie für Deutsches Recht. p. 129.

In den Bergen des Dukagjin: in Shala, Shoshi, Kir, Gjaj, Plan und Toplan.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 149–174.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 149–156.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 157–159.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 160–165.

- ↑ Elsie 2010, p. 248.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 166–169.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 170–174.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 175–196.

- 1 2 Durham 1928, p. 27.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 175–177.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 178–180.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 183–185.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 186–192.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, pp. 193–196.

- ↑ The Tribes of Albania; History, Society and Culture. Robert Elsie.

External links

- Great Britain Admiralty War Staff. "Albanian frontiers (map)". Library of Congress. 88694278.