Qing dynasty coinage

Qing dynasty coinage (simplified Chinese: 清朝货币; traditional Chinese: 清朝貨幣; pinyin: Qīngcháo Huòbì) was based on a bimetallic standard of copper and silver coinage. The Manchu Qing dynasty ruled over China from 1644 until it was overthrown by the Xinhai revolution in 1912.[1][2] The Qing dynasty saw the transformation of a traditional cash coin based cast coinage monetary system into a modern currency system with machine-struck coins, while the old traditional silver ingots would slowly be replaced by silver coins based on those of the Mexican peso.[3][4] After the Qing dynasty was abolished its currency was replaced by the Chinese yuan by the Republic of China.

Later Jin dynasty coinage (1616–1636)

Prior to the establishment of the Qing dynasty, the Jurchen people (later renamed the Manchus) created the Jin dynasty after an earlier Jurchen dynasty. For this reason historians refer to this state as the "Later Jin".[5] Nurhaci had united the many tribes of the Jianzhou and Haixi Jurchens under the leadership of the Aisin Gioro clan,[6] and later ordered the creation of Manchu script based on the Mongolian vertical script.[7][8] Hong Taiji renamed the Jin dynasty into the Qing dynasty,[9] and the Jurchen people into the Manchu people, while adopting more ethnic inclusive policies towards Han Chinese people in order not make the same mistakes as the Mongols did before him.[10][11]

In 1616 the Jurchens began producing their own cash coins, the coins issued under Nurhaci were written in an older version of Manchu script without any diacritics, and generally bigger than Later Jin coins with Chinese inscriptions. Under Hong Taiji these coins bore the legend that they had a nominal weight of 10 qián (or 1 tael) modelled after contemporary Ming dynasty coinage, but in reality weighed less.

The following coins were issued by the Jurchens (later Manchus) before the establishment of the Qing:[12][13][14]

| Inscription | Latin script | Denominations | Years of mintage | Image | Khan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᠠᠪᡴᠠᡳ ᡶᡠᠯᡳᠩᡤᠠ ᡥᠠᠨ ᠵᡳᡴᠠ | Abkai fulingga han jiha | 1 wén | 1616–1626 |  | Abkai fulingga Khan |

| 天命通寳 | Tiān Mìng Tōng Bǎo | 1 wén | 1616–1626 |  | Abkai fulingga Khan |

| ᠰᡠᡵᡝ ᡥᠠᠨ ᠨᡳ ᠵᡳᡴᠠ | Sure han ni jiha | 10 wén | 1627–1643 | _-_Scott_Semans.png) | Sure Khan |

History

In 1644 the Manchus captured Beijing from the Shun dynasty,[15] and then marched south capturing the forces loyal to the Ming. One of the first monetary policies they enacted was accepting Ming dynasty cash coins at only half the value of Qing dynasty cash coins, because of this Ming era coinage was removed from circulation to be melted into Qing dynasty coinage, this is why in modern times even Song dynasty coins are more common than those from the more recent Ming dynasty.

Early history

At first the Qing government set the exchange rate between bronze and silver at 1 wén of bronze per lí (釐, or 厘) of silver, and 1000 lí of silver would be 1 tael (两), thus one string of 1000 bronze cash coins equated to a single tael of silver.

The Shunzhi Emperor created the Ministry of Revenue and the Ministry of Public Works in Beijing to oversee the casting of bronze cash coins, these ministries produced 400,000 strings of cash coins annually. Later the Shunzhi Emperor ordered military garrisons to start minting their own coinage, and though the official weight for cash coins was first set at 1 qián, in 1645 this increased to 1.2 qián, and by 1651 this had become 1.25 qián. In 1660 the order was given to re-open provincial mints and have them cast their mint names in Manchu script.[16]

The coins produced under the Shunzhi Emperor were modeled after Tang dynasty Kai Yuan Tong Bao coins, as well as early Ming dynasty coins, and have a Chinese mint mark on their reverses these were produced from 1644 until 1661, though these coins had a large range of mint marks from various provinces all over China, from 1644 until 1645 there were also Shùn Zhì Tōng Bǎo (順治通寶) coins being cast with blank reverses.[17]

Kangxi era

Under the Kangxi Emperor in 1662 the government closed all provincial mints with the notable exception of the one in Jiangning, but in 1667 all of the provincial mints were re-opened but many closed down again soon afterwards as the price of copper had steadily increased. Those responsible for the transportation of copper rarely made the mints in time, and while copper prices were rising daily the Ministry of Revenue still maintained a fixed rate of exchange between copper and silver causing many provincial mints to quickly lose money, while on paper they were still profitable.[18]

In 1684 the amount of copper in the alloys if cash coins was reduced from 70% to 60% all while the standard weight was lowered to 1 qián again, while the central government's mints in Beijing started producing cash coins with a weight of 0.7 qián. By 1702 all provincial mints were closed again due to the aforementioned circumstances.[19]

Yongzheng era

Under the Yongzheng Emperor various measures were undertaken to ensure a vast supply of cash coins, though the weight was increased to 1.4 qián per wén, the copper content was lowered from 60% to 50% in 1727. In 1726 the Ministry of Revenue was split into 4 agencies each named after a wind direction, and in 1728 all provincial mints were ordered to open again as only the mint of Yunnan province was operating prior to this order, and finally in 1728 the Ministry of Public Works mint was split into a "new Ministry of Public Works mint", and an "old Ministry of Public Works mint". Though by 1733 the Qing government realised that the costs of making standard cash coins at a weight of 1.4 qián was too much, so they lowered it back to 1.2 qián.[20]

In 1725 the province of Yunnan had 47 operating furnaces. In 1726 the governour of Yunnan, Ortai made the province's coin minting industry more profitable by implementing new systems for regular, and supplemental casting as well as for casting scrap metal making sure that only regular cast coins would carry full production costs, he also closed down mints in the province with a lower production efficiency and started exporting Yunnan's coins to other provinces. This system proved so successful that other provinces started to adopt these reforms.[21]

Qianlong era

During the first few years of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor China had suffered from a shortage of cash coins due to the contemporary scarcity of copper, but soon Yunnan's copper mines started producing a large surplus of copper allowing the Qing government to swiftly increase the money supply and minting more coins at a faster pace. In the middle of the Qianlong era as much as 3,700,000 strings of cash were produced annually. In 1741 coins were ordered to be made of an alloy of 50% copper, 41.5% zinc, 6.5% lead, and 2% tin to reduce the likelihood of people melting down coins to make utensils, all while the Qing government encouraged to sell their utensils to the state mints to be melted into coinage. By the end of the Qianlong era, Yunnan's copper mines started depleting the production of cash coins, and the copper content was debased once more. 1794 all provincial mints were forced to close their doors, but subsequently reopened in 1796.[22]

During the Battle of Ngọc Hồi-Đống Đa in 1788 special Qián Lóng Tōng Bǎo coins were minted with An nan (安南) on their reverse sides as a payment for soldiers.[23]

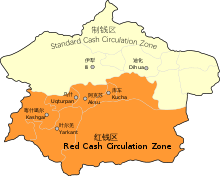

Qianlong coinage in Xinjiang

In 1759 the Qing dynasty had conquered most of what would become the Xinjiang province,[24] as native coinages of the old Khanates were being deprecated in favour of Chinese cash coins, new cash coins made of pure copper to reflect local pūl (ﭘول) coins were minted that were red in colour and weighed 2 qián.[25][26] Under Qianlong new mints were established in Yining City,[27] Aksu, Yarkant,[28] and Ushi city. Xinjiang coins of the Qianlong era had reverse inscriptions in both Manchu and Turkic scripts. Even after the death of the Qianlong Emperor the Jiaqing Emperor ruled that 1 in 5 coins produced in Xinjiang should bear the inscription Qián Lóng Tōng Bǎo (乾隆通寶) to honour Qianlong, and celebrate his conquest of the region, this rule stayed in place even until the end of the Qing dynasty.[29]

Jiaqing era

Under the Jiaqing Emperor the Chinese population had reached 300,000,000 which was twice as much as just a century prior, famines had plagued the land, the government was corrupt, and hoards of secret Anti-Manchu organisations popped up everywhere, stability would not return until 1803 but this had come at tremendously high costs.[30] The Qing government started to increase quotas for the production of copper cash coins while constantly changing the standard content of the alloys beginning with 60% copper, and 40% zinc in 1796 to 54% copper, 43% zinc, and 3% lead not long after. Corruption plagued the provincial mints, and the exchange rate between cash and taels rose from 900 wén for 1 tael of silver to 1200 wén for a single tael, this was also due to a large outflow of silver to European and American merchants which pressured the Chinese monetary system. Under the Jiaqing Emperor an annual quota of 2,586,000 strings of cash coins for production was set, but in reality this number was rarely met.[31]

Daoguang era

Under the Daoguang Emperor China's silver reserves were depleting due to the trade of opium with other countries, and as Chinese cash coins were based on the silver standard this eventually lead to the debasement of Qing era cash coinage under Daoguang because the costs of producing cast copper coins was higher by about one third than the face value of the cast coins themselves, by 1845 2,000 wén was needed for a single tael of silver. Coins produced under the Daoguang Emperor tend to be diminutive compared to earlier Qing dynasty coinage because of this reason.[32][33] Under the Daoguang Emperor a new mint was established at Kucha in the Xinjiang province with coins cast there bearing the mark "庫" as well as coins with the reverse side inscription of "新" to circulate within the aforementioned province that was far away from China proper.

Inflation during the 19th century

_-_DSCN8151BB.jpg)

Under the Xianfeng Emperor several large wars such as the Nian, Miao, Panthay and Taiping rebellions, and the Second Opium War plagued the Qing dynasty, because of the military actions undertaken in these wars copper could no longer be shipped from the south (particularly from the copper rich Yunnan province) leading not only to a debasement of the copper content in cash coins, but also to a large increase in denominations to keep paying for the high military expenditures and other governmental costs, this inevitably lead to large inflation.[34][35] Various other factors also lead to inflation such as a rapidly increasing population, and famines.

The Xianfeng Emperor also started issuing large quantities of new banknotes, the Hù Bù Guān Piào (戶部官票), and Dà Qīng Bǎo Chāo (大清寶鈔) were issued as a means to pay for the wars fought under Xianfeng, but because of the Qing dynasty's low silver reserves these banknotes couldn't be backed up.

Coinage struck under Xianfeng wasn't standard either though ranging from denominations as low as 1 wén to as high as 1000 wén, it wasn't uncommon for coins with a face value of 50 wén to be heavier than 100 wén coins, and 100 wén coins to be even be heavier than 1000 wén coins. Despite the larger denominations, existing lower denominations were also heavily debased with the 1 wén denomination being standardised back to 1 qián.[36][37][38] Despite the larger denominations of 500 and 1000 being ordered to be cast of pure copper, and illegal producers of these coins were executed by the government en masse, the general population still had no faith in the larger denominations (mostly because a 1000 wén coin only had the intrinsic value of twenty 1 wén cash coins), eventually all denominations larger than 10 wén were withdrawn and the 10 wén coins would continue to be minted in Beijing until the reign of the Guangxu Emperor.

Tongzhi era

For the first year of the Tongzhi Emperor he bore the reign name of "Qixiang", though a few coins with this inscription were cast they were never put into circulation. Tongzhi's mother the Empress Dowager Cixi changed his reign name to Tongzhi in 1862. Tongzhi's reign saw the end of the Taiping rebellion and the beginning of a large Muslim revolt in Xinjiang. The era also saw the rise of the Self-Strengthening Movement which wanted to adopt western ideas into practice in China including reforming the monetary system.[39]

The coins produced under the Tongzhi Emperor remained of inferior quality with the 10 wén coin being reduced from 4.4 to 3.2 qián in 1867. Copper shortages remained and illegal casting would only become a larger problem as the provincial mints remained closed or barely productive. The first machine-struck cash coins were also produced under the Tongzhi Emperor in Paris at the request of governour Zuo Zongtang in 1866, but the government of the Qing refused to introduce machine-made coinage.[40]

Modernisation under the Guangxu Emperor

Under the Guangxu Emperor various attempts at reforming the Qing dynasty's currency system were implemented. Machine-made copper coins without square holes were introduced in Guangdong province in 1899,[41] and by 1906 15 machine operated mints operated in 12 provinces. The introduction of these machine-struck coins marked the beginning of the end of coin casting in China. In 1895 the Guangzhou Machine Mint had 90 presses becoming the largest mint in the world followed by the British Royal Mint with only 16 presses.

Many provinces were still slow to adopt machine mints, often due to the high costs associated with them, the machine mint of Tianjin cost 27,000 taels of silver but the cost of making a single string of machine-struck 1 qián cash coins more than twice as high as their face value forcing the Tianjin mint to buy more furnaces until it eventually had to close down in 1900.[42]

Guangxu's reign saw the reclamation of Xinjiang and the presuming of minting red cash there, while Japanese experts revitalised the copper mining industry in Yunnan and many new veins of copper were discovered giving the government more resources to cast (and later strike) coins again.

The new coins often bore the inscription Guāng Xù Yuán Bǎo (光緒元寶) with an image of a Dragon and featured English, Chinese, and Manchu inscriptions. Further these coins tended to have their relation with China's older coinages (most often with cash coins) on the bottom, or their value in relation to silver coinage, and the Manchu words indicated the place of mintage. Meanwhile, the 10 wén "traditional" cash coins were discontinued as the production of these more modern coins began.[43]

In 1906 the General Mint of the Ministry of the Interior and Finance in Tianjin started issuing a new copper coin called the Dà Qīng Tóng Bì (大清銅幣), which like Guāng Xù Yuán Bǎo coins featured the image of a Chinese dragon, and had English, Chinese, and Manchu inscriptions with the English inscription reading "Tai-Ching-Ti-Kuo Copper Coin" in Wade-Giles, coins minted under the Guangxu Emperor featured the inscription of the Chinese characters Guāng Xù Nián Zào (光緒年造). These coins were minted in denominations of 2 wén, 5 wén, 10 wén, and 20 wén and would soon be issued by various mints across the Chinese provinces. These coins were first issued by the Ministry of the Interior and later by the Ministry of Revenue and Expenditure.[44]

Coinage under the Xuantong Emperor

Under the Xuantong Emperor both traditional copper cash coins, and modern machine-struck coins continued to be minted simultaneously, though only the Ministry of Revenue in Beijing and a few provincial mints continued to cast traditional cash coins as most mints had started to exclusively produce machined coins, and Kucha was the only mint still operating in Xinjiang casting "red cash" under the Xuantong Emperor. Under the Xuantong Emperor Beijing's 2 central government operated mints would close. In 1910 new machine-made coins were issued.

New denominations introduced in 1910 include.

| Denomination (in Chinese) | Denomination (in English) |

|---|---|

| 一厘 | 1 lí |

| 五厘 | 5 lí |

| 一分 | 1 fēn |

| 二分 | 2 fēn |

| 壹圓 | 1 yuán |

These denominations weren't produced in large numbers as the Qing dynasty would be overthrown by the Xinhai revolution only a year later.[45] By the end of the Qing dynasty the government's attempts at modernising the monetary system had failed and machined coins circulated alongside traditional coinages, this situation would continue under the Republic of China.

Copper coinage

The copper coinage of the Qing dynasty was officially set at an exchange rate of 1000 wén (or cash coins) for one tael of silver, however actual market rate often changed from low as 700 wén for 1 tael of silver to as high as 1200 wén for a single tael of silver during the 19th century. The actual exchange rates were dependent on a variety of factors such as the quantity of the coinage on the market and quality of individual coins. Most government cast coinage entered the market through soldiers.[46][47]

Because casting is a very simple process many private (illegal) mints started producing fake cash coins known as Sīzhùqián (私鑄錢) because government mints often couldn't meet the market's demand for money, as there barely was a difference in quality between "real" or Zhìqián (制錢) and "fake" coins, the sizhuqian were just as widely accepted by the general population as means of payment. Though barter had remained common during most of the Qing era, by the mid 19th century the Chinese market had evolved to be highly monetised. Due to the inflation caused by various military crises under the Xianfeng Emperor new larger denomination cash coins were issued, cash coins of 4 wén and higher being referred to as Dàqián (大錢).

By the late Qing dynasty it had become apparent that carrying strings of cash coins was inconvenient compared to modern currencies. In 1900, 8 shillings converted into 32.6587 kilograms of copper cash coins and it was noted that if one of the straw strings holding the coins would break that it would cost more picking those coins up in time than the value retrieved from those coins.[48][49] This was one of the factors leading Chinese people to more readily accept the modernisation of the currency.

Purchasing power of cash coins during the Qing dynasty

At the time that Wu Jingzi's the Scholars was written in the 18th century 3 wén could buy a steamed bun, 4 wén could buy school food, 16 wén was enough for one bowl of noodles, and the annual tuition fee for school could be covered by 2,400 wén, but due to inflation the purchasing power of cash coins would decline in the next century.

| Period | Amount of rice for 1000 wén (or 1 string of cash coins)[50] |

|---|---|

| 1651–1660 | 99.6 kg |

| 1681–1690 | 136 kg |

| 1721–1730 | 116 kg |

| 1781–1790 | 57.3 kg |

| 1811–1820 | 25.2 kg |

| 1841–1850 | 21.6 kg |

Machine-struck cash coins

_-_scanned_image.png)

Due to a shortage of copper at the end of the Qing dynasty, the mint of Guangzhou, Guangdong began striking round copper coins without square holes in 1900. Tóngyuán (銅元) or Tóngbǎn (銅板) and they were struck in denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 30 wén. These struck coins were well received because of their higher quality compared to cast coins and their convenience in carriage, as well as their uniform weight and copper content compared to the less consistent alloys of cast Chinese coinage. As these coins were profitable to manufacture it did not take long before other provinces started making machine-struck cash coins too, and soon 20 bureaus were opened across China.[51] As these coins became more common they eventually replaced the old cast coins as the main medium of exchange for small purchases among the Chinese people.

Counterfeit machine-struck coins

Not long after these new copper coins were introduced, black market counterfeit versions of the 10 wén appeared, illegal mints opened all over China and started producing more coins than the Qing government's set quotas allowed there to be circulating on the market. Both Chinese and foreigners soon started producing struck cash coins of inferior quality often with traces of the Korean 5 fun coins they were overstruck on, or with characters and symbols not found on official government issued coins. These coins were often minted by Korean businessmen and former Japanese Samurai looking to make a profit on exchanging the low value copper coins into silver dollars as a single silver dollar had the purchasing power of 1000 Korean fun. The majority of the counterfeit coins bear the inscription that they were minted in either Zhejiang province or Shandong province, but they circulated all over the coastal regions of China.[52][53]

List of cash coins issued by the Qing dynasty

Qing dynasty era cash coins generally bear the reign title of the Emperor in Chinese characters, with only a single change of reign title occurring with the Qixiang Emperor becoming the Tongzhi Emperor by decision of his mother, Empress Dowager Cixi.[54]

| Inscription | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Hànyǔ Pīnyīn | Denominations | Years of mintage | Image | Emperor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shunzhi Tongbao | 順治通寶 | 顺治通宝 | shùn zhì tōng bǎo | 1 wén | 1643–1661 |  | Shunzhi Emperor |

| Kangxi Tongbao | 康熙通寶 | 康熙通宝 | kāng xī tōng bǎo | 1 wén | 1661–1722 |  | Kangxi Emperor |

| Yongzheng Tongbao | 雍正通寶 | 雍正通宝 | yōng zhèng tōng bǎo | 1 wén | 1722–1735 | Yongzheng Emperor | |

| Qianlong Tongbao | 乾隆通寶 | 乾隆通宝 | qián lóng tōng bǎo | 1 wén, 10 wén | 1735–1796 (1912)[lower-alpha 1] |  | Qianlong Emperor |

| Jiaqing Tongbao | 嘉慶通寶 | 嘉庆通宝 | jiā qìng tōng bǎo | 1 wén | 1796–1820 | Jiaqing Emperor | |

| Daoguang Tongbao | 道光通寶 | 道光通宝 | dào guāng tōng bǎo | 1 wén, 5 wén, 10 wén | 1820–1850 |  | Daoguang Emperor |

| Xianfeng Tongbao | 咸豐通寶 | 咸丰通宝 | xián fēng tōng bǎo | 1 wén, 5 wén, 10 wén, 50 wén, 100 wén | 1850–1861 | _1850%E2%80%931861_Qing_Dynasty_cash_coin.png) | Xianfeng Emperor |

| Xianfeng Zhongbao | 咸豐重寶 | 咸丰重宝 | xián fēng zhòng bǎo | 4 wén, 5 wén, 8 wén, 10 wén, 20 wén, 30 wén, 40 wén, 50 wén, 100 wén | 1850–1861 | Xianfeng Emperor | |

| Xianfeng Yuanbao | 咸豐元寶 | 咸丰元宝 | xián fēng yuán bǎo | 80 wén, 100 wén, 200 wén, 300 wén, 500 wén, 1000 wén | 1850–1861 |  | Xianfeng Emperor |

| Qixiang Tongbao | 祺祥通寶 | 祺祥通宝 | qí xiáng tōng bǎo | 1 wén | 1861 | Tongzhi Emperor | |

| Qixiang Zhongbao | 祺祥重寶 | 祺祥重宝 | qí xiáng zhòng bǎo | 10 wén | 1861 | _Early_T%C3%B3ng_Zh%C3%AC_cash_coin_(1861).png) | Tongzhi Emperor |

| Tongzhi Tongbao | 同治通寶 | 同治通宝 | tóng zhì tōng bǎo | 1 wén, 5 wén, 10 wén | 1862–1875 | Tongzhi Emperor | |

| Tongzhi Zhongbao | 同治重寶 | 同治重宝 | tóng zhì zhòng bǎo | 4 wén, 10 wén | 1862–1875 | Tongzhi Emperor | |

| Guangxu Tongbao | 光緒通寶 | 光绪通宝 | guāng xù tōng bǎo | 1 wén, 10 wén | 1875–1908 | Guangxu Emperor | |

| Guangxu Zhongbao | 光緒重寶 | 光绪重宝 | guāng xù zhòng bǎo | 5 wén, 10 wén | 1875–1908 | Guangxu Emperor | |

| Xuantong Tongbao | 宣統通寶 | 宣统通宝 | xuān tǒng tōng bǎo | 1 wén, 10 wén | 1909–1911 | Xuantong Emperor |

Silver coinage

During the early days of the Qing dynasty silver Spanish dollars, known to the Chinese as "double balls" (雙球) because of the two globes featured on the coins, continued to circulate in the coastal areas of China, while sycees were regularly manufactured inland. Trade with the Spanish Empire continued as Chinese junks brought on average 80,000 pesos from Manila on every voyage, and by the mid-18th century the amount rose to 235,370,000 pesos. A lot of silver from Portugal, the Dutch Republic, and Japan continued to enter China during this period. After Mexico had become independent Mexican pesos (or "Eagle coins", 鷹洋) replaced the old Spanish dollars while the old Spanish dollars still remained important in China, the Treaty of Nanking ending the First Opium War in 1842 had its payments accounted in Spanish dollars.[55]

Many other forms of silver coins circulating in China caused the Qing government to eventually start producing its own silver coinage (銀圓 or 銀元) in 1821 with the first machine-struck silver coins being made a year later by the Jilin Arsenal in 1822. In 1887 Zhang Zhidong, the Viceroy of Liangguang started producing silver coinage in Guangzhou, these coins weighed 0.73 taels and had the English inscription of "Kwang-tung Province, 7 Mace and 3 Candareens" and were decorated with a large Dragon earning them the nickname "Guangdong Dragon dollars" (廣東龍洋) or they were referred to simply as "Yuán", an abbreviation of Yuánbǎo (元寶) which was featured on the inscription,[56] though this design was similar to silver Japanese coins circulating in China at the time which also featured a Dragon. These coins proved popular and soon other provinces started to cast their own variants of these silver coins. These coins were manufactured independently by each province and it wasn't until 1910 that the government of the Qing dynasty standardised them at 0.72 taels.[57][58]

The usage of silver coins was more common in Chinese trading ports after these were opened to foreign traders, eventually the usage of foreign paper money to exchange silver also became popular as foreign banks like The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation began issuing banknotes denominated in taels for the Chinese market.[59]

Prior to 1 tael being standardised at 50 g. by the government of the People's Republic of China in 1959, the weight "tael" differed substantially from province to province, the Qing government maintained that 1 tael equals 37.5 g. and this measurement was referred to as the Kuping tael (庫平两), and by official Qing government standards 1 Kuping tael = 10 Mace = 100 Candareens. Under the Guangxu Emperor several Kuping tael coins were struck in Tianjin from 1903 until 1907, and mostly served as salary for the soldiers. Despite the central government's attempts at unifying the standards provincial coinage remained the de facto standard across China.[60] Under the Xuantong Emperor another attempt at standardising the Qing dynasty's silver coinage was made in 1911 (Xuantong 3) a large amount of "dragon dollars" bearing the inscription "壹圓" (yīyuán) were minted, these were the only Qing dynasty coins with that inscription and also featured the English legend "One Dollar". These coins were all cast at the Central Tianjin Mint.[61]

After the fall of the Qing dynasty sycees were demonetised in 1933 and Qing dynasty silver coins in 1935 as they were replaced with paper money.[62]

Private production of silver coinage

Despite silver making up the other half of the bimetallic system of the Qing dynasty's coinage it wasn't officially produced by the government until the later period of the dynasty where the silver coins would be based on the foreign coins that already circulated in China. Government ledgers used it as a unit of account, in particular the Kuping Tael (庫平兩) was used for this. For most of its history both the production and the measurements of silver was in the hands of the private market which handled the exclusive production of silver currency, the greatest amount of silver ingots in China was produced by private silversmiths (銀樓) in professional furnaces (銀爐), only a very small amount of silver ingots was issued by government-owned banks during the late 19th century. While assayers and moneychangers had control over its exchange rates, for this reason no unified system of silver currency in place in China but a series of different types of silver ingots that were used in various markets throughout the country. The most common form of silver ingots (元寶 or 寶銀) in China were the "horse-hoof ingots" (馬蹄銀) and could weigh as much as fifty taels, there were also "middle-size ingots" (中錠) which usually weigh around 10 taels, "small-size ingots" (小錠)[lower-alpha 2] that weighed between one and five taels, and "silver crumbs" (碎銀 or 銀子).[lower-alpha 3] All freshly cast ingots were sent to official assayers (公估局) where their weight and fineness were marked with a brush. However these determinations were only valid on the local market and nowhere else do silver ingots were constantly reassessed which was the daily business of Chinese money changers. In fact, silver ingots were weighed in each single transaction.[63]

Silver ingots were traded at different rates that were dependent on the purity of their silver content, the average ones were known as Wenyin (紋銀) or Zubao (足寶) which had (theoretical) purity of .935374, meanwhile specimens that were of higher quality and content were referred to by true surplus that was to be advanced on changing. Exempli gratia a silver ingot known as an "Er-Si Bao" (二四寶) with a weight of fifty taels was valued at 52.4 taels. Likewise other silver standards in China were all geared to the Wenyin such as the Shanghai tael that used in the foreign concession of the city, for instance, was called the Jiuba Guiyuan (九八規元) because it had 98 per cent of the purity of the Shanghai standard tael (規元). The standard tael of Tianjin was called the Xinghua (行化) and that of Hankou was known as the Yangli (洋例).[63]

Names of weights and standards of Chinese silver ingots

The most commonly used English term to describe Chinese silver ingots is "sycee" (細絲), which comes from a Cantonese term meaning "fine weight" where the "weight" (絲, sī) represents 0.00001 tael. However a large number of regional terms and names for these silver ingots existed throughout China, these names include:[63]

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Region | Image of a regionally produced sycee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuansi | 元絲 | 元丝 | Southern Jiangsu and Zhejiang. | |

| Yanche | 鹽撤 | 盐撤 | Jiangxi, Hubei, and Hunan. | |

| Xicao Shuisi | 西鏪水絲 | 西鏪水丝 | Shandong. | |

| Tucao | 土鏪 | 土鏪 | Sichuan. | |

| Liucao | 柳鏪 | 柳鏪 | Sichuan. | |

| Huixiang | 茴香 | 茴香 | Sichuan. | |

| Yuancao | 元鏪 | 元鏪 | Shaanxi and Gansu. | |

| Beiliu | 北流 | 北流 | Guangxi. | |

| Shicao | 石鏪 | 石鏪 | Yunnan. | |

| Chahua | 茶花 | 茶花 | Yunnan. |

Among the aforementioned regional names other designations for sycees were Qingsi (青絲), Baisi (白絲), Danqing (單傾), Shuangqing (雙傾), Fangcao (方鏪), and Changcao (長鏪) among many others.[63]

Aside from the large number of names for sycees that existed in China there was also a wealth of different weight standards for taels that existed that were different from market to market. One of the larger variants of the tael was the Kuping Tael (庫平兩) which was used by the Chinese Ministry of Revenue for both weight measurements as well as a unit of account used during tax collections. In 1858 a new trade tax was introduced which used the Sea Customs tael (海關兩) as a unit of account, meanwhile in Guangdong the Canton Tael (廣平兩) was used when trading with foreign merchants. Another unit of account that was used was the Grain Tribute Tael (漕平兩) which was used for measuring and accounting the tribute the imperial Chinese government received in grain.[63]

Gold coinage

During the later years of the Manchu Qing dynasty, the coinage system was scattered with central government-made coins, local coins and some foreign currencies circulating together in the private sector of China, resulting in a great deal of currency confusion, this has made both fiscal and financial management in China quite difficult. In an attempt to bring order to this chaos some people such as Chen Zhi started advocating for China to place its currency on the gold standard.[64] In the year Guangxu 30 (1904) the Ministry of Revenue created a concrete implementation for the manufacture of gold coins,[65] while in 1905 the government of the Qing dynasty reformed the currency system to allow for gold coins, these would be cast by the Tianjin General Mint operated by the Ministry of Revenue with the inscription Da Qing Jinbi (大清金幣), only a small number of trial coins with this inscription were ever cast that were not meant for general circulation as the gold reserves of the Qing dynasty proved insufficient. These coins weighed 1 Kuping Tael and were cast in the years Guangxu 32 (1906) and Guangxu 33 (1907) and featured a design of a Chinese dragon on one side and the inscription on the other with the year of casting shown in Chinese cyclical years.[66][67]

Mint marks

In total there had been more than 50 local mints established that each bore their own unique mint marks, however several of these mints operated only for a brief time before discontinuing their casting of cash coins, mint marks on Qing dynasty coinage can be categorised into 7 main categories based on the scripts on the reverse sides of the coins: 1) only have Manchu script mint marks; 2) Only have mint marks in Chinese script with the weight of the coin in lí; 3) have both Manchu, and Chinese script mint marks; 4) only have a single Chinese character indicating the mint on the top of the reverse side; 5) Only contain the character "一" (1) on the reserve 6) have both Manchu, and Chinese scripts together on the right and left sides of the coin, plus the denomination of the denomination on the top and bottom, and 7) have Chinese, Manchu, and Arabic script together on the reverse side of the coin.[68]

Chinese mint marks

Mint marks on coins issued from 1644 until 1661:

| Mint mark (Traditional Chinese) | Mint mark (Simplified Chinese) | Issuing office | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| 戶 | 户 | The Ministry of Revenue, Beijing | |

| 工 | 工 | The Ministry of Public Works, Beijing | |

| 陝 | 陕 | Xi'an, Shaanxi | |

| 臨 | 临 | Linqing garrison, Shandong | _-_Linqing%2C_Shandong_Mint_-Scott_Semans.jpg) |

| 宣 | 宣 | Xuanhua garrison, Zhili | |

| 延 | 延 | Yansui garrison, Shanxi | |

| 原 | 原 | Taiyuan, Shanxi | |

| 西 | 西 | Shanxi provincial mint | |

| 雲 | 云 | Miyun garrison, Zhili | |

| 同 | 同 | Datong garrison, Shanxi | |

| 荊 | 荆 | Jingzhou garrison, Hubei | |

| 河 | 河 | Kaifeng, Henan | |

| 昌 | 昌 | Wuchang, Hubei | |

| 甯 | 宁 | Jiangning, Jiangsu | |

| 江 | 江 | Nanchang, Jiangxi | |

| 浙 | 浙 | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | |

| 福 | 福 | Fuzhou, Fujian | |

| 陽 | 阳 | Yanghe garrison, Shaanxi | |

| 襄 | 襄 | Xiangyang, Hubei |

From 1653 until 1657 another type of cash coin was simultaneously cast with the above series, but these coins contained the extra inscription of "一厘" (Equals one lí of silver) on the back. They were generally minted at the same mints as the above cash coin series but weren't minted at the Yansui garrison, the Shanxi province, and the Jingzhou garrison while another mint at Jinan, Shandong was opened for these coins, with coins cast there bearing the mark "東". Additionally there were also coins cast with no mint mark that only contain the character "一" (1) on their reserves indicating their value in Ií.

Between 1660 and 1661 cash coins were manufactured with both a Manchu (on the left), and a Chinese (on the right) character as mint marks. The following mints produced these coins:

| Mint mark (Traditional Chinese) | Mint mark (Simplified Chinese) | Issuing office | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| 陝 | 陕 | Xi'an, Shaanxi | |

| 臨 | 临 | Linqing garrison, Shandong | |

| 宣 | 宣 | Xuanhua garrison, Zhili | |

| 薊 | 蓟 | Jizhou garrison, Zhili | |

| 原 | 原 | Taiyuan, Shanxi | |

| 同 | 同 | Datong garrison, Shanxi | |

| 河 | 河 | Kaifeng, Henan | |

| 昌 | 昌 | Wuchang, Hubei | |

| 甯 | 宁 | Jiangning, Jiangsu | |

| 寧 | 宁 | Ningbo, Zhejiang | |

| 江 | 江 | Nanchang, Jiangxi | |

| 浙 | 浙 | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | |

| 東 | 东 | Jinan, Shandong |

Under the reign of the Kangxi Emperor coins with only Manchu reverse inscriptions and both Manchu and Chinese reverse inscriptions were cast. The coins of the Kangxi Emperor were also the basis for the coins of the Yongzheng, Qianlong, and Jiaqing Emperors.

Under the Kangxi Emperor coins were produced at these mints:

| Mint mark (Traditional Chinese) | Mint mark (Simplified Chinese) | Issuing office | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| 同 | 同 | Datong garrison, Shanxi | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 福 | 福 | Fuzhou, Fujian | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 臨 | 临 | Linqing garrison, Shandong | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 東 | 东 | Jinan, Shandong | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 江 | 江 | Nanchang, Jiangxi | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 宣 | 宣 | Xuanhua garrison, Zhili | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 原 | 原 | Taiyuan, Shanxi | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 蘇 | 苏 | Suzhou, Jiangsu | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 薊 | 蓟 | Jizhou garrison, Zhili | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 昌 | 昌 | Wuchang, Hubei | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 甯 | 宁 | Jiangning, Jiangsu | |

| 河 | 河 | Kaifeng, Henan | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 南 | 南 | Changsha, Hunan | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 廣 | 广 | Guangzhou, Guangdong | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 浙 | 浙 | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 臺 | 台 | Taiwan | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 桂 | 桂 | Guilin, Guangxi | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 陝 | 陕 | Xi'an, Shaanxi | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 雲 | 云 | Yunnan Province | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 漳 | 漳 | Zhangzhou, Fujian | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

| 鞏 | 巩 | Gongchang, Gansu | |

| 西 | 西 | Shanxi provincial mint | |

| 寧 | 宁 | Ningbo, Zhejiang | _-_John_Ferguson.jpg) |

Manchu mint marks

_mint_mark_on_a_Xu%C4%81n_T%C7%92ng_T%C5%8Dng_B%C7%8Eo_(%E5%AE%A3%E7%B5%B1%E9%80%9A%E5%AF%B6).jpg)

ᠶᠣᠨᠨ mint mark on a Xuān Tǒng Tōng Bǎo (宣統通寶) coin indicating that it was cast in Kunming, Yunnan.

Another series of bronze cash coins was introduced with Manchu script on the reverse sides of the coin from 1657, many mints contained the Manchu word ᠪᠣᠣ (Boo) on the left, which is Manchu for "寶" (indicating "treasure" or "currency") on the obverse side of these coins. To the right of them would often appear a word indicating the issuing agency of the coin. Qing dynasty coinage with exclusive Manchu mint marks are by far the most commonly produced type. Large denomination coins of the Xianfeng Emperor bore Manchu mint marks on the left and right sides of the reverse sides, and the value of the coin on the top and bottom. Coins with exclusive Manchu inscriptions continued to be cast until the end of the Qing dynasty.[69][70][71][72][73]

Manchu mint marks are:

| Mint mark | Möllendorff | Place of minting | Province | Time in operation | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠴᡳᠣᠸᠠᠨ | Boo Ciowan | Ministry of Revenue (hùbù, 戶部), Beijing | Zhili | 1644–1911 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠶᡠᠸᠠᠨ | Boo Yuwan | Ministry of Public Works (gōngbù, 工部), Beijing | Zhili | 1644–1908 | |

| ᠰᡳᡠᠸᠠᠨ | Siowan | Xuanfu | Zhili | 1644–1671 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠰᠠᠨ | Boo San | Xi'an | Shaanxi | 1644–1908 | |

| ᠯᡳᠨ | Lin | Linqing | Shandong | 1645–1675 | |

| ᡤᡳ | Gi | Jizhou | Zhili | 1645–1671 1854–Unknown | |

| ᡨᡠᠩ | Tung | Datong | Shanxi | 1645–1649 1656–1674 | |

| ᠶᡠᠸᠠᠨ (1645–1729) ᠪᠣᠣ ᠵᡳᠨ (1729–1908) | Boo Yuwan (1645–1729) Jin (1729–1908) | Taiyuan | Shanxi | 1645–1908 | |

| ᠶᡡᠨ | Yūn | Miyun | Zhili | 1645–1671 | |

| ᠴᠠᠩ (1646–1729) ᡠ (1729–1908) | Cang (1646–1729) U (1729–1908) | Wuhan | Hubei | 1646–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡥᠣ | Boo Ho | Kaifeng | Henan | 1647 1729–1731 1854–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡶᡠᠩ | Boo Fung | Fengtian | Fengtian | 1647–1648 1880–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠴᠠᠩ (1647–1729) ᡤᡳᠶᠠᠩ (1729–1908) | Boo Chang (1647–1729) Giyang (1729–1908) | Nanchang | Jiangxi | 1647–1908 | |

| ᠨᡳᠩ | Ning | Jiangning | Jiangsu | 1648–1731 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡶᡠ | Boo Fu | Fuzhou | Fujian | 1649–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠵᡝ | Boo Je | Hangzhou | Zhejiang | 1649–1908 | |

| ᡩᡠᠩ (1649–1729; 1887–1908) ᠪᠣᠣ ᠵᡳ (1729–1887) | Dung (1649–1729; 1887–1908) Boo Ji (1729–1887) | Jinan | Shandong | 1649–1738 1854–1870 1887–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠶᠣᠨᠨ | Boo Yonn | Kunming | Yunnan | 1653–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠴᡠᠸᠠᠨ | Boo Cuwan | Chengdu | Sichuan | 1667–1908 | |

| ᡤᡠᠩ | Gung | Gongchang | Gansu | 1667–1740 1855–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠰᡠ | Boo Su | Suzhou | Jiangsu | 1667–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠨᠠᠨ | Boo Nan | Changsha | Hunan | 1667–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡤᡠᠸᠠᠩ | Boo Guwang | Guangzhou | Guangdong | 1668–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡤᡠᡳ | Boo Gui | Guilin | Guangxi | 1668–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ | Boo Giyan | Guiyang | Guizhou | 1668–1908 | |

| ᠵᠠᠩ | Jang | Zhangzhou | Fujian | 1680–1682 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡨᠠᡳ | Boo Tai | Taiwan-Fu | Taiwan | 1689–1740 1855–Unknown | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠠᠨ | Boo An | Jiangning, Jiangsu | Anhui | 1731–1734 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡷᡳ | Boo Jy | Baoding | Zhili | 1745–1908 | |

| ᠶᡝᡵᡴᡳᠶᠠᠩ | Yerkiyang | Yarkant | Xinjiang | 1759–1864 | |

| ᡠᠰᡥᡳ | Ushi | Uši | Xinjiang | 1766–1911 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡳ | Boo I | Ghulja | Xinjiang | 1775–1866 | |

| ᡩᡠᠩ | Dung | Dongchuan | Yunnan | 1800–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡬᡳ | Boo Gi | Unknown | Hebei (1851–1861) Jilin (1861–1912) | 1851–1912 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡩᡝ | Boo De | Jehol | Zhili | 1854–1858 | |

| ᡴᠠᠰᡥᡤᠠᡵ | Kashgar | Kashgar | Xinjiang | 1855–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡩᡳ (1855–1886; 1907–1908) ᠶᡠᠸᠠᠨ (1886–1907) | Boo Di (1855–1886; 1907–1908) Yuwan (1886–1907) | Ürümqi | Xinjiang | 1855–1864 1886–1890 1907–1908 | |

| ᡴᡠᠴᠠ | Kuca | Kucha | Xinjiang | 1857–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠵᡳᠶᡝᠨ | Boo Jiyen | Tianjin | Zhili | 1880–1908 | |

| ᡥᡡ | Hu | Dagu | Zhili | 1880–1908 | |

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡠ | Boo U | Wuchang | Hubei | ||

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡤᡠᠩ | Boo Gung | Kunshan | Jiangsu | ||

| ᠠᡴᠰᡠ | Aksu | Aksu | Xinjiang | ||

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᡩᠣᠩ | Boo Dong | Unknown | Yunnan | ||

| ᠪᠣᠣ ᠵᡳᠩ | Boo Jing | Unknown | Hubei |

Chinese, Manchu, and Uyghur mint marks

Additionally coins from the Southern Xinjiang province can also have 3 different scripts on the reverse side of the coin being Manchu, Chinese, and Arabic scripts. An example would be a coin from Aksu would have the Chinese 阿 on top, the Manchu ᠠᡴᠰᡠ on the left, and the Uyghur Perso-Arabic ئاقسۇ on the right. Another differentiating feature of Xinjiang coins is that they tend to be more red in colour reflecting on the colour of the local copper mined in the province.

Tibetan coinage under the Qing

.jpg)

Up until the 20th century Chinese silver ingots (sycee) were used for larger transactions, and were referred to as rta rmig ma ("horse hoof") and normally weighed 50 tael, or 50 srang. During the Qing period there also circulated silver ingots of smaller size, named gyag rmig ma (yak hoof) and yet smaller ones, referred to as ra rmig ma (goat hoof). In the early 20th century sycees were worth about 60–70 Indian rupees, the ingots of medium size 12–14 rupees and the smallest ingots 2–3 rupees.[74] British-Indian authors occasionally refer to the silver bars found in Tibet, some of which were imported from Kashgar, Xinjiang as "yambus", an expression which was derived from the Chinese "yuánbǎo". Silver cins that were extensively used in southern Tibet were supplied by the Nepalese Malla Kingdoms and the first kings of the subsequent Shah dynasty from about 1640 until 1791.[75] However, due to a dispute between Nepal and Tibet regarding the silver content of the coinage supplied by Nepal, the export of these coins was disrupted after the mid-eighteenth century.[76][77][78][79][80] In order to overcome the shortage of coins in Tibet at that time, the Tibetan government started striking its own coins, modelled on Nepalese prototypes. This occurred in 1763–64 and again in 1785 without any interference by the Chinese government.[76][77][78][80] After this, the Nepalese repeatedly attempted to reintroduce their silver coins back on the Tibetan market and the Tibetan government repeatedly attempted to mint its own silver coinage.[80] And in order to keep the profitable trade with Tibet the Nepalese attempted to invade Tibet in 1788 and again in 1790/91, eventually the Tibetan and Chinese armies drove the Nepalese out in 1792.

The Qing government took this opportunity to tighten their grip on Tibet's monetary system, and issued an edict which among other dispositions stipulated the introduction of a new silver coinage, struck in the name of the Qianlong Emperor. Simultaneously banning the import of silver coins from Nepal. Though due to a shortage of silver the Qing allowed the Tibetan government to strike coins derived from the Nepalese silver coins to circulate in Tibet under the supervision of both the Qing and Tibetan governments. In 1791 the Qing planned to cast copper cash coins in Tibet, however this was deemed too expensive to transport copper from China proper to Lhasa. From this point onward Tibetan silver coinage bore the reign names and eras of Qing Emperors.

During the second part of the 19th and the first third of the 20th century numerous foreign silver coins circulated in Tibet. Most of them were traded by weight, such as Mexican and Spanish American silver dollars, Russian roubles and German marks. The exception were British Indian rupees, particularly the ones with the portrait of Queen Victoria, which widely circulated in Tibet and were mostly preferred to Tibetan coins. These rupees were of good silver and had a fixed value, exchanging for three tangkas until about 1920,[81][82] and in later years of the 20th century they considerably increased in value. The Qing government saw the popularity of the Indian rupees among Tibetan traders with misgivings and in 1902 started striking their own rupees which were close copies of the Indian Victoria rupees, the portrait of the Queen being replaced by that of a Chinese mandarin, or, as most numismatists believe, of the Guangxu Emperor of China. The Chinese rupees were struck in Chengdu during the Qing dynasty.[83] These coins would continued to be produced by the Republic of China.[84]

Xinjiang

Early history

The region of Xinjiang was conquered by the Qing dynasty after the Dzungar–Qing Wars ended with the territory of the Dzungar Khanate coming under Manchu administration by 1759, the Muslim leaders and the armies of the conquered territories fled to Badakhshan. On 28 July 1759 the leader of Badakhshan formally recognised Manchu rule.[85][86][87][88][89] Under Qing rule, Xinjiang was administered as 3 circuits, the southern circuit being the former Dzungar Khanate paid with pūl coins. Zhao Hui, General of Ili requested to the Qianlong Emperor permission to take pūl coins from the locals and use the copper to cast Qing Chinese cash coins, Zhao Hui ensured that these cash coins would weigh the same as the old pūl coins and would preserve the previous Dzungar monetary system. General Zhao Hui set the exchange rate between pūls and Qing cash coins at 2 Dzungar pūls for 1 cash, further Xinjiang cash coins being the same weight as Dzungar pūl coins weighed 2 qián (7.46 g) as opposed to the 1.2 qián (4.476 g) circulating in contemporary China proper. As pūl coins were nearly made of pure copper the new cash coins created from them would become red in colour earning them the nickname of "Red Cash".[90] As it was beyond the skills of the primitive Chinese metallurgists to remove the non-copper from the coinage 98% of the content of "Red Cash" was copper with the rest often being either zinc or lead as the Qing didn't have the expertise yet to remove this, the rest metal often came from scrap metal collected to cast cash coins.[91]

When "Red Cash" coins were introduced in the southern circuit in 1760 they were valued at 10 wén (or 10 cash coins from China proper), but a few years later this halved. Meanwhile, "Red Cash" from the other circuits were exchanged at par with standard cash coins.[92]

Establishing mints in Xinjiang

As the state mint of the Dzungar Khanate was located in Yarkant, and many Dzungar pūl coins still circulated there as well as in Kashgar, and Hotän a new mint was opened in Yarkant in 1760 employing 99 people (among them 8 Han Chinese from Shaanxi who were previously employed by a provincial mint there).[93] Melting and casting equipment was transported from the Shaanxi province to Yarkant for the new mint to start producing coinage, not only Dzungar pūl coins were used but also leftover equipment from the military. The coins produced at this mint show the mint mark both in the Manchu and Uyghur languages. The Qing dynasty was able to claim 2.6 million pūl coins from the population at an exchange rate of 2 pūls for 1 cash, but in 1762 the exchange rate was placed at par causing the Qing to eventually discontinue the exchange in 1768 as the pūl would continue circulate, and the Yarkant mint was forced to import copper from the Turfan mint. In 1769 the Yarkant mint was closed having produced between two and three thousand strings of "Red Cash".[94][95]

A mint opened in Aksu in 1761, as Aksu had a high amount of natural copper resources near it, as well as gaining a lot of scrap copper through taxes. The mint itself was large housing 6 furnaces and employing 360 people including technical staff from China proper to oversee the production of "Red Cash" in Aksu. Most cash coins produced in Aksu almost exclusively circulated in the 4 largest cities of the former Dzungar Khanate.[96]

As the General of Ili made Turfan the administrative capital of Xinjiang's southern circuit the Aksu mint was relocated there in 1766, and after the Yarkant mint had closed down in 1769 the Turfan mint became the sole mint of the southern circuit. At first the standard weight of 2 qián (the same as Dzungar pūl coins circulating at the time) was maintained but a copper shortage in 1771 caused the "Red Cash" from Turfan to become a half qián lighter, and 3 years later had its weight brought at par with cash coins from China proper. In 1799 the Turfan mint was brought back to Aksu because of that city's increasing economic dominance over the region of Southern Xinjiang.[97]

Cash coins in the Northern and Eastern circuits

Unlike the southern circuit Xinjiang's other regions did not cash coins that deviated from those produced in China proper, various factors played into this decision. Mostly in the north the people that lived there were nomads and didn't have an established monetary system in place, and there were no prior government regulations on trade. Also many Han Chinese people started migrating from other parts of China to the northern and eastern regions of Xinjiang bringing with them their cash coins. Because of these reasons the Qing dynasty didn't create a new monetary system as they had done in the former Dzungar Khanate but implemented the system used by the rest of the Qing.[98]

A mint was established at Yining City in 1775,[99] the mint itself was a large complex with 21 buildings. In 1776 copper was found near Yining causing the production of cash coins at the mint to rise.

Daoguang era

In 1826 Jahangir Khoja with soldiers from the Khanate of Kokand occupied the southern circuit of Xinjiang temporarily losing Kashgar, Yarkant, and Hotän to this rebellion. The Daoguang Emperor sent 36 thousand Manchu soldiers to defeat this rebellion. As more soldiers had entered Xinjiang the price of silver went down, while that of copper went up. In 1826 1 tael of silver was worth 250 or 260 "Red Cash" while in 1827 good had decreased to 100 or sometimes even as low as 80. Despite the soldiers returning to Manchuria the original exchange rates did not restore causing the mint of Aksu to close, as the Aksu mint closed down less money was circulating on the market. In 1828 monetary reforms were implemented to keep the current weight of "Red Cash" but increase their denominations to 5, and 10 wén (while weighing the same) with 70% of Aksu's annual production being 5 wén coins, and 30% being 10 wén but the production of "Red Cash" itself was reduced by two and a half thousand strings. Later the Daoguang Emperor ordered the weight of "Red Cash" to further decrease in order to maximise profits.[100]

Xianfeng and Tongzhi eras

Under the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor "Red Cash" coins were excessively manufactured negating the reforms implemented by Daoguang causing inflation in the region. As the Taiping rebellion and the Second Opium War had prompted the Qing government to start issuing high denomination cash coins in other parts of the Qing dynasty, this soon spread to Xinjiang mainly due to the decreased subsidies for military expenditures in Xinjiang lowering the soldiers' salaries. In 1855 new denominations of 4 wén and 8 wén were introduced at the Yining mint, further the Ürümqi mint started issuing cash coins with high denominations in response. New mints were established at Kucha, and Kashgar while the Yarkant mint was re-opened. Coins also started being cast in bronze, brass, lead, and iron; this system received a chaotic response from Xinjiang's market. From 1860 denominations higher than 10 wén were discontinued.[101] Only coins of 4, 5, and 10 wén were cast at Xinjiang's provincial mints under the Tongzhi Emperor. Cash coins that had a higher denomination than 10 was being collected from the population to be smelted into lower denominations, while the higher denominations that stayed on the market were accepted only lower than their face value.[102][103]

Arabic cash coins of Rashidin Khan Khoja

During the Dungan revolt from 1862 to 1877, Sultan Rashidin Khan Khoja proclaimed a Jihad against the Qing dynasty in 1862, and captured large cities in the Tarim Basin. He issued Chinese-style cash coins minted at the Aksu, and Kucha mints with exclusive Arabic inscriptions, these coins were only briefly minted as Rashidin Khan Khoja would be betrayed and murdered by Yakub beg in 1867.[104]

Guangxu and Xuantong eras

As the chaotic circulation of various denominations of cash coins had continued, this invited foreign silver money from Central Asia to start circulating in the Xinjiang region. After the Russian Empire had occupied the northern region of Xinjiang in 1871 Russian rubles started circulating. Eventually 3 parallel currency systems were in place while pūl coins from the Dzungar Khanate kept circulating in Kashgaria a century after the region was annexed by the Qing dynasty. The Dungan revolt lead by the Tajik Muhammad Yaqub Beg was defeated in 1878 during the Qing reconquest of Xinjiang,[105][106] and the Russians returned the territory they had occupied after signing a treaty in 1880 at Yining.[107][108] In 1884 Xinjiang was upgraded to the status of "province" ending military and Lifan Yuan rule over the region, while the "Red Cash" system was reintroduced in Kashgaria now at a value of 4 wén. However, at the end of the reign of the Guangxu Emperor "Red Cash" was discontinued at the Aksu mint in 1892 because of the rising costs of charcoal needed to produce the coins. The Aksu mint was transferred to Kucha mint. Though the Kashgar mint re-opened in 1888 it outsourced some of the production of "Red Cash" to Kucha and Aksu resulting in cash coins being cast with the Chinese mint mark of Kashgar but the Manchu and Arabic mint marks of the actual mint of casting. The kashgar mint closed down in 1908. The Kucha mint introduced new obverse inscriptions for cash coins minted there with the Guang Xu Ding Wei (光緒丁未) in 1907, and Guang Xu Wu Shen (光緒戊申) in 1908, however production didn't last very long as the Kucha mint finally closed down in 1909.[109]

Under the Xuantong Emperor "Red Cash" continued to be produced but at lower number than before at the Turpan mint, but as the Turpan mint closed down in 1911 a year before the fall of the Qing dynasty the production of "Red Cash" officially ended.[110]

Commemorative coins

- In 1713 a special Kāng Xī Tōng Bǎo (康熙通寶) cash coin was issued to commemorate the sixtieth birthday of the Kangxi Emperor, these bronze coins were produced with a special yellowish colour, and these cash coins believed to have "the powers of a charm" immediately when it entered circulation, this commemorative coin contains a slightly different version of the Hanzi symbol "熙", at the bottom of the cash, as this character would most commonly have a vertical line at the left part of it but did not have it, and the part of this symbol which was usually inscribed as "臣" has the middle part written as a "口" instead. Notably, the upper left area of the symbol "通" only contains a single dot as opposed of the usual two dots used during this era. Several myths were attributed to this coin over the following three-hundred years since it has been cast such as the myth that the coin was cast from molten down golden statues of the 18 disciples of the Buddha which earned this coin the nicknames "the Lohan coin" and "Arhat money". These commemorative kāng xī tōng bǎo cash coins were given to children as yā suì qián (壓歲錢) during Chinese new year, some women wore them akin to how an engagement ring is worn today, and in rural Shanxi young men wore this special kāng xī tōng bǎo cash coin between their teeth like men from cities had golden teeth. Despite the myths surrounding this coin it was made from a copper-alloy and did not contain any gold but it was not uncommon for people to enhance the coin with gold leaf.[111]

- In 1905 the Qing dynasty issued special silver 1 tael Guāng Xù Yuán Bǎo (光緒元寶) coins celebrating the 70th birthday of Empress Dowager Cixi.[112][113] These coins feature the Chinese character for longevity (壽) surrounded by 2 Imperial dragons reaching out to the wish-granting pearl.

Foreign silver "dollars" circulating in the Qing dynasty

Under the reign of the Qing dynasty foreign silver coins entered China in large numbers, these silver coins were known in China as the Yangqian (洋錢, "ocean money") or Fanqian (番錢, "barbarian money"). During the 17th and 18th centuries Chinese trade with European merchants was in a constant rise, as the Chinese weren't consumers of larger contingents of commodities from Europe they largely received foreign silver currency for their exports. As the Europeans discovered a vast quantity of silver mines in the Americas the status of silver rose to be that of an international currency and silver became the most important metal used in international transactions globally, this also had a profound impact on the value of Chinese silver. Other than trade, Europeans were interested in the Chinese market due to the high interest rates on loans paid out to Chinese merchants in Guangzhou by the Europeans. Another common reason why European merchants traded with the Chinese was because as various types of precious metals had different prices around the world the price of gold was much lower in China than in Europe. Meanwhile, Chinese merchants used copper-alloy cash coins to purchase silver from the Europeans and Japanese during this period.[114]

Silver coins largely circulated in the coastal provinces of China and the most important form of silver were the foreign silver coins that circulated in China and these were known under many different names often dependent on the imagery depicted on them. According to the 1618 book Dong-Xiyang Kao (東西洋考) a chapter on the local products of the island of Luzon in the Spanish East Indies mentions that Chinese observers witnessed a silver coin that came from New Spain while other Chinese observers would claim that it came from Spain. These silver dollars came from the North American part of New Spain to the Philippines through the Manila galleons and were brought to Guangzhou, Xiamen, and Ningbo by Chinese merchants. Trade with the Kingdom of Portugal commenced after the Portuguese occupation of Macau in 1557 and two decades later trade with Castile was established, trade with the Dutch Republic started in 1604 with their occupation of the Penghu islands, and with the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1729. By the end of the eighteenth century China was also trading with the newly established United States of America. Despite Chinese merchants valuing both foreign silver coins (銀元) and Chinese silver ingots (銀兩) based on their silver content, the government of the Qing dynasty still enforced the opinion that the silver coins that originated in foreign countries was somehow of inferior value than the Chinese sycees. Yet the private Chinese markets didn't share this opinion with the imperial Qing government as the populations of the coastal provinces (and Guangdong most in particular) held the foreign silver coins in high esteem due to various advantages such as their fixed nominal values and their consistently reliable fineness of their silver content which all made them be used for transactions without having to undergo a process of assaying or weighing as is expected of sycees.[114]

The year 1814 the market value of 1 silver foreign coin in Guangzhou was never less than 723 Chinese cash coins, while in other provinces like Jiangsu and Zhejiang they were even worth more eight hundred cash coins, or foreign silver coins could be traded for 0.73 tael of silver each.[115][116] The following decades the exchange ratee would only rise and a single foreign silver coin would be worth between 1,500 and 1,900 Chinese cash coins. The Chinese authorities during this period for this reason often raised the proposition to ban the circulation of foreign silver coins within Chinese territory, on the suspicion that "good" Chinese silver went to foreign markets, while the "inferior" foreign silver coins caused the markets of southern China to inundate. There was evidence that the Qing dynasty indeed suffered a net loss of 11% when changing Chinese into foreign silver. During the initial period of the 19th century the imperial Chinese administration suspected that more silver was being exported than imported causing the Chinese to slowly develop a silver deficit as the trade balance fell on the negative side of the spectrum for the Qing. However, as the government of the Qing dynasty never collected and compiled any statistics on the private trade of silver it is very difficult to generate any accurate hard numbers on these claims. According to Hosea Ballou Morse the turning point for the Chinese trade balance was in the year 1826, during this year the trade balance allegedly fell from a positive balance of 1,300,000 pesos to a negative one of 2,100,000 pesos.[114]

According to the memorial by the governor of Fujian, L. Tsiuen-Sun published on November 7, 1855 it is noted that the governor witnessed that the foreign silver coins that had been circulating in Jiangnan were held in great esteem by the local people and that the most excellent of these coins weighed 7 Mace and 2 Candareens while their silver content was only of 6 Mace and 5 Candareens. He also noted that these coins were greatly used in Fujian and Guangdong and that even the most defaced and mutilated of these coins were valued on par with Chinese sycees, in fact he noted that everyone in possession of a sycee would exchange these for foreign silver coins known as Fanbing (番餅, "foreign cakes") due to their standard weights and sizes. Meanwhile, the governor noted that in the provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu these chopped dollars didn't circulate as much in favour of a currency he calls "bright money". Originally a dollar was worth upwards of seven Mace; the value gradually rose over time to eight Mace, and by 1855 it exceeded nine Mace.[117]

Early trade prior to the establishment of the Qing

Between the 16th and 18th centuries a vast amount of foreign silver coins arrived in the Qing dynasty. During the early years of Sino-Portuguese trade at the port of Macau, the merchants from the Kingdom of Portugal purchased an annual amount of two million taels worth of Chinese commodities, additionally the Portuguese shipped about 41 million taels (or 1.65 million kilograms) of silver from Japan to China until the year 1638. A century earlier in the year 1567 the Spanish trade port in the city of Manila was opened which until the fall of the Ming dynasty brought over forty million Kuping Taels of silver to China with the annual Chinese imports numbering at 53,000,000 pesos (each peso being 8 real) or 300,000 Kuping Taels. During the Ming dynasty the average Chinese junk which took the voyage from the Spanish East Indies to the city of Guangzhou took with it eighty thousand pesos, a number which increased under the Qing dynasty as until the mid-18th century the volume of imported Spanish pesos had increased to 235,370,000 (or 169 460,000 Kuping Tael). The Spanish mention that around 12,000,000 pesos were shipped from Acapulco de Juárez to Manila in the year 1597 while in other years this usually numbered between one and four million pesos. The Japanese supplied 11,250 kilograms of silver to China by merchants in direct trade annually prior to the year 1600, after the Sakoku policy was enacted by the Tokugawa shogunate in the year 1633 only 350 Japanese trade vessels sailed for China, however each of these ships had more than one thousand tons of silver.[114]

Names used by the Chinese for foreign silver coins

List of names used for foreign silver coins during the reign of the Qing dynasty:[114]

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Literal translation | Foreign silver coin | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maqian Majian | 馬錢 馬劍 | 马钱 马剑 | "Horse money" "Horse-and-sword [money]" | Dutch ducaton | |

| Shangqiu Shuangzhu Zhuyang | 雙球 雙柱 柱洋 | 双球 双柱 柱洋 | "Double ball [dollar]" "Double-pillar [dollar]" "Pillar dollar" | Spanish dollars issued under King Philip V and King Ferdinand VI | |

| Benyang Fotouyang | 本洋 佛頭洋 | 本洋 佛头洋 | "Main dollar"[lower-alpha 4] "Buddha-head dollar" | Spanish Carolus dollar | |

| Sangong[lower-alpha 5] | 三工 | 三工 | "Three Gong's" | Spanish dollars produced under King Charles III | |

| Sigong | 四工 | 四工 | "Four Gong's" | Spanish dollars produced under King Charles IV | |

| Huabianqian | 花邊錢 | 花边钱 | "Decorated-rim money" | Machine-struck Spanish Carolus dollars produced after 1732 | |

| Yingyang | 鷹洋 英洋 | 鹰洋 英洋 | "Eagle coin" "English Dollar"[lower-alpha 6] | Mexican peso | |

| Shiziqian | 十字錢 | 十字钱 | "Cross money" | Portuguese cruzado | |

| Daji Xiaoji | 大髻 小髻 | 大髻 小髻 | "Large curls" "Small curls"[lower-alpha 7] | Spanish dollar | |

| Pengtou | 蓬頭 | 蓬头 | "Unbound hair"[lower-alpha 8] | United States dollar United States trade dollar | |

| Bianfu | 蝙蝠 | 蝙蝠 | "Bat"[lower-alpha 9] | Mexican peso or United States dollar | |

| Zhanrenyang Zhangyang | 站人洋 仗洋 | 站人洋 仗洋 | "Standing person dollar" "Weapon dollar" | British dollar | |

| Longyang Longfan Longyin | 龍洋 龍番 龍銀 | 龙洋 龙番 龙银 | "Dragon dollar" "Dragon foreign [dollar]" "Dragon silver" | Silver Dragon |

Spanish dollars and Mexican pesos

The paramount foreign silver coin in Chinese history was the Spanish piece of eight (or 8 reals and commonly called a peso) which was known popularly in English as the Spanish dollar, however to the Chinese this coin was popularly known as the double ball (雙球) because its obverse depicted two different hemispheres of the globe based on the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas which divided the world between the Crown of Castile and the Kingdom of Portugal and the Algarves. The silver "double ball" coins were issued under the reigns of King Philip V and King Ferdinand VI between the years 1700 and 1759 and were cast in the Kingdom of Mexico in the Viceroyalty of New Spain which was signified by the mint mark "Mo" ("M[exic]o") and featured Latin texts such as "VTRAQUE VNUM" ("both [hemispheres] are one [empire]") and "HISPAN·ET·IND·REX" ("king of Spain and the Indies") preceded with the name of the reigning monarch. The globes on these early Spanish dollars were flanked by two crowned pillars (representing the Pillars of Hercules), these pillars were entwined with S-shaped banners (which is also the origin of the peso sign, $). Under the reign of King Charles III the design was changed and the pillars were moved to the reverse of the coin while of the Spanish coat-of-arms were superseded by a portrait of the reigning monarch, because of this these coins were known as "Carolus dollars" or columnarius ("with columns") in the West,[118] while the Chinese referred to them as Zhuyan (柱洋, "pillar dollar"). Additionally on some Carolus dollars the inscription "PLVS VLTRA" was found.[119] The Spanish Carolus dollars always had a standard weight of 27.468 grams, while their silver content was lowered from 0.93955 to a purity of only 0.902. From the year 1732 onwards these coins were manufactured in Mexico City and other parts of Spanish America. The portraits of kings Charles III and Charles IV (with the "IV" written as "IIII") were featured on these coins, the Chinese referred to the Latin numeral "I" as "工" causing the silver coins of Charles III to be known as Sangong (三工) while those produced under the reign of Charles IV were known as Sigong (四工) coins. Additionally the depiction of the reigning Spanish monarch inspired the Chinese people to refer these Carolus dollars as Fotou Yang (佛頭洋, "Buddha-head dollar"). The Carolus dollar came in the denominations of ½ real, 1 real, 2 reales, 4 reales, and 8 reales of which the highest denomination had a diameter of forty millimeters and a thickness of 2.5 millimeters. All Carolus dollars issued under the reign of Charles III to China were produced in the year 1790 while those under Charles IV all date from 1804 onwards.[114]

In daily exchange the Chinese rated the 8 reales Carolus dollars at 0.73 Kuping Tael and was one of the most important forms of exchange, the Treaty of Nanking that ended the First Opium War had its payments measured in Spanish Carolus dollars. According to estimates by the British East India Company the Qing dynasty imported 68,000,000 Taels worth of foreign silver coins between the years 1681 and 1833, this sets China's imports over 100,000,000 foreign silver coins with the bulk of these being Spanish Carolus dollars produced in Spanish America that entered China through trade.[114]

The Chinese preference of the old Spanish Carolus dollars over newer European silver coinage, Mexican real, Peruvian real (later the Peruvian sol, and the Bolivian sol (later the Bolivian boliviano) was considered to be "unjustified" by many foreign powers, it took the combined diplomatic interventions of the United Kingdom, France and the United States to lead to a proclamation by Shanghainese superintendent of customs, Chaou, to issue a decree that was dated 23 July 1855, commanding the general circulation of all foreign silver coins, whether they were new or old coinages. One of the reasons why the circulation of other silver coins other than the Spanish Carolus dollars because the Spanish government has long since stopped the production of these coins as the Spanish American wars of independence cut them off of the majority of their colonies, this had the effect that while no new Spanish Carolus dollars were being produced many Chinese merchants started demanding more money for them as these coins started slowly but gradually disappearing from the Chinese market. As many foreign nations started trading with China the Chinese regarded these non-Spanish currencies as "new coins" and often discounted them from 20 to 30 percent due to the suspicion that they had a lower silver content than the Spanish Carolus dollars.[120]

After Mexican independence was declared the Mexican Empire started issuing silver pesos with their coat of arms on them, these silver coins were brought to China from 1854 and were known to the Chinese as "Eagle coins" (鷹洋), though they have commonly been incorrectly called "English dollars" (英洋) because they were mostly brought to China by English merchants.[121] The denominations of these coins remained the same as with the earlier Spanish dollars but the currency unit "real" was replaced with "peso".[114] Initially the Chinese market didn't respond positively to this change of design and accepted the Mexican pesos at a lower rate than they did the Spanish Carolus dollars due to a fear that they might have a lower silver content, but after members the customs house of Shanghai were inviter to see the manufacturing process of the Mexican peso by the foreign mercantile community they concluded that these new coins were of equal quality and purity as the old Spanish Carolus dollars and decreed that after the next Chinese new year Chinese merchants in Shanghai can't demand a premium on transactions made in Mexican pesos and that all foreign coins would have to be judged on their intrinsic value and not on the fact if it was a Spanish Carolus dollar or not, the reason why this decree was passed was due to the widespread dishonesty among the Chinese merchants overcharging transactions paid in Mexican pesos claiming that only Spanish Carolus dollars were trustworthy. This request was also forwarded to all governors of the coastal provinces, however despite the push by the Chinese authorities of the Qing to bring fiscal parity between the Spanish Carolus dollar and the Mexican peso, the Chinese people still held high esteem for the former and the prejudices favouring Spanish Carolus dollars did not cease.[122]

On the 26th day of the 1st month during the year Xianfeng 6 (March 2, 1856) the Taoutae (or highest civil officer) of Luzhou-fu, Longjiang-fu, and Taichangzhou who also served as the acting Commissioner of Finance for Luzhou-fu as other places in Jiangnan issued a proclamation condemning the practice of discounting the value of good Spanish dollars and making it illegal to do so, Taoutae Yang cited that there were cunning stockjobbers who have been getting up a set of clever nicknames which they give to Spanish Carolus dollars out of self-interest to try and devalue certain coins and heavily discount them. Some time after the proclamation these dealers stopped fearing the law and continued their practice. It was notable that certain types of Spanish dollars known as the "copper-mixed-dollar", the "inlaid-with-lead-dollar", the "light-dollar", and the "Foochoow dollar" were particularly targeted this proclamation as they were perceived to be intrinsically of less value, according to Eduard Kann in his book The Currencies of China he reports in Appendix IV: "A feature of Foochow currency is the chopped, or rather the scooped, the scraped, the cut, the punched dollar. This maltreatment often obliterates all trace of the original markings, some assuming the shape and appearance of a mushroom suffering from smallpox. It is obvious that such coins must pass by weight ..."[122] The Taoutae argued that the money-changers used absurd tricks in attempting to find a flaw in the Spanish dollar while he argued that these coins were both not lighter in weight nor did they feel inferior in quality when held. The Taoutae argued that the numerous chops on them are proof of the fact that they have been rigorously checked and verified by various Chinese authorities over an extended period of time and that the chopping of these Spanish dollars did not negatively influence them in any way. Money-changers who engaged in illegally downgrading and devaluing Spanish dollars by assigning these nicknames to them in Jiangnan were placed in a cangue. A similar law was also passed by the province of Zhejiang and government clerks aiding these dishonest shopkeepers were also subject to punishment if discovered.[122]

Other foreign silver coins

The silver ducats of the Dutch Republic were known as the Maqian (馬錢) or Majian (馬劍) to the Chinese and it has been estimated that between the years 1725 and 1756 ships from the Netherlands bought in Canon merchandise for 3.6 million taels worth of silver, but between the years 1756 and 1794 this was only 82.697 tael. In the late 18th century the Dutch silver ducats were primarily circulating in the coastal provinces of Guangdong and Fujian. The smallest of the Dutch ducats had a weight of 0.867 Kuping Tael. The Portuguese cruzado started circulating in the southern provinces of China during the latter part of the 18th century and was dubbed the Shiqiqian (十字錢) by contemporary Chinese merchants. The denominations of the Portuguese cruzado during that time were 50 réis, 60 réis, 100 réis, 120 réis, 240 réis, and 480 réis with the largest coin weighing only 0.56 Kuping Tael.[123][124] The silver coins of the Japanese yen were first introduced in the year 1870 and circulated in the eastern provinces of the Qing dynasty, they were locally known as Longyang (龍洋, "dragon dollars") or Longpan (龍番) because they featured a big dragon and bore the Kanji inscription Dai Nippon (大日本). These Japanese coins were dominated in yen (圓) and would later serve as the model for the Chinese silver coins produced at the end of the Qing period.[114]

Prior to the first opium war began around a dozen different types of foreign silver coins were circulating in China, among these was a small amount of French silver écu coins, however Spanish Carolus dollars were by far the most numerous as various trade companies such as the British East India Company purchased Chinese products such as tea with them, as all other foreign currencies were forbidden by the Qing as a means to accept payment for tea. In the year 1866 a new mint was opened in British Hong Kong and the British government started the production of the silver Hong Kong dollar (香港銀圓) that all featured a portrait of the reigning British monarch, Queen Victoria. As these Hong Kong dollars didn't have as high of a silver content as the Mexican peso these silver coins were rejected by Chinese merchants and had to be demonetised mere 7 years after they were introduced. In the year 1873 the government of the United States created the American trade dollar which was known to the Chinese as the Maoyi Yinyuan (貿易銀元), this coin specially designed for use in the trade with the Qing dynasty. However, because its silver content was lower than that of the Mexican peso, it suffered the same fate as the silver Hong Kong dollar and was discontinued 14 years after its introduction.[125] Afterwards another silver British coin was introduced inspired by the American trade dollar that became known as the British dollar or British trade dollar, these coins featured the inscription "One Dollar" (in English, Chinese, and Malay) and had the portrait of the female personification of the United Kingdom Britanny on them, these silver coins were introduced in the year 1895, and were called either Zhanrenyang (站人洋) or Zhangyang (仗洋) by the Chinese.[114]

See also

Notes