Red Turban Rebellion (1854–1856)

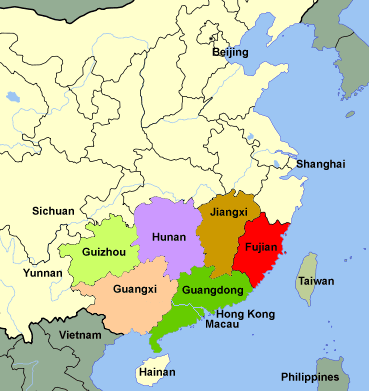

The Red Turban Rebellion of 1854–1856 was a rebellion by members of the Tiandihui or Heaven and Earth Society (天地會) in the Guangdong province of South China.

| Red Turban Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

The initial core of the rebels were Tiandihui secret societies that were involved in both revolutionary activity and organised crime, such as prostitution, piracy and opium smuggling. Many lodges were formed originally for self-defence in feuds between locals and migrants from neighbouring provinces.[1] They were organised into scattered local lodges each under a lodge-master (堂主), and in October 1854 elected Li Wenmao and Chen Kai as joint alliance-masters (盟主).[2]

In Summer 1854, 50,000 outlaws, proclaiming a restoration of the Ming dynasty, captured Qingyuan. This roused the Tiandihui to revolt in the city of Conghua, forty miles Northeast of the provincial capital. The Red Turbans were formed by religious members from Tiandihui, such as Qiu Ersao who joined the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with thousands more. In September, forces commanded by Taiping-affiliated Ling Shiba captured Luoding and made it their headquarters.[3] Ling Shiba was a member of the Tiandihui.[4]:660[5][6]

Viceroy of Guangdong Xu Guangjin (徐廣縉) sent braves (勇, or irregular militia) to the border to deal with the situation, but these mostly defected to the rebels. Provincial governor Ye Mingchen then formulated a strategy of bribing lodge leaders to defect, which was successful in bringing Ling to heel, and the Emperor promoted him to Viceroy.[3] Ye would later be in charge of purging Guangdong of any anti-government outlaw. Over one million people from Guangdong were sentenced to death and executed.[7]

Cantonese dissatisfaction of the Qing state resulted in the growth of lawlessness, while flooding of the Pearl River added to their economic woes. The Taiping victory in the capture of Nanjing galvanised the Tiandihui to redouble their revolutionary efforts.[8] A group, allied with the Small Swords Society in neighbouring Fujian province, succeeded in seizing the city of Huizhou, and rebel leader He Liu proceeded to capture the city of Dongguan, followed by Chen Kai's capture of the major city of Foshan on 4 July 1854.[9]

The Red Turbans did not succeed in taking the city of Guangzhou, but fought through much of the country round it for more than a year.[10]:473 Failure to coordinate had exhausted the supplies of the rebel alliance, and they faltered during the attack on the provincial capital Guangzhou where the gentry had succeeded in raising a force of militia to defend the city alongside the British Royal Navy which intervened on the government side.[11]

By 1856, after failing to capture Guangzhou, Red Turban forces, hoping to continue to resist the Qing state, retreated north and occupied parts of Guangxi province, proclaiming the Dacheng Kingdom and managed to hold out for nine years, others fighting their way through government-held territory in Hunan province and finally to Jiangxi province where they coalesced with the Taiping forces of Shi Dakai; some of these were consolidated as the Flower Flag Force (花旗军) of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. Many were crushed by the Xiang Army en route.[12][13]:

The British involvement in the counter-insurgency by selling British weaponry to government forces and allowing the Chinese shipping carrying them to avoid rebel attack by using the British flag, would lead to the Second Opium War when a pirate ship with a British flag was captured by Chinese government forces.[14]

References

- Kim, Jaeyoon (2009). "The Heaven and Earth Society and Red Turban Rebellion in Late Qing China". Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 3 (1): 4–5. ISSN 1934-7227.

- Kim, Jaeyoon (2009). "The Heaven and Earth Society and Red Turban Rebellion in Late Qing China". Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 3 (1): 7–9. ISSN 1934-7227.

- Wakeman, Strangers at the Gate pp. 132-133

- S. Y. Teng (December 1968). Strangers at the Gate: Social Disorder in South China, 1839-1861. by Frederick Wakeman (review) Political Science Quarterly 83 (4): 658–660. (subscription required)

- Yeh Ming-Ch'en: Viceroy of Liang Kuang 1852-8 By J. Y. Wong, Senior Lecturer in History J Y Wong

- Guangdong and Chinese Diaspora: The Changing Landscape of Qiaoxiang - Yow Cheun Hoe - Google Books

- Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration Between the United States and South China, 1882–1943. p. 26.

- Kim, Jaeyoon (2009). "The Heaven and Earth Society and Red Turban Rebellion in Late Qing China". Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 3 (1): 67. ISSN 1934-7227.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1997). Strangers at the Gate: Social Disorder in South China, 1839-1861 (Reprint, revised ed.). University of California Press. pp. 137–139. ISBN 0520212398.

- June Mei (October 1979). Socioeconomic Origins of Emigration: Guangdong to California, 1850–1882. Modern China 5 (4): 463–501. (subscription required)

- Kim, Jaeyoon (2009). "The Heaven and Earth Society and Red Turban Rebellion in Late Qing China". Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 3 (1): 10–11. ISSN 1934-7227.

- Kim, Jaeyoon (2009). "The Heaven and Earth Society and Red Turban Rebellion in Late Qing China". Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 3 (1): 22–23. ISSN 1934-7227.

- Steven Platt (2012). Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom. Knopf

- Kim, Jaeyoon (2009). "The Heaven and Earth Society and Red Turban Rebellion in Late Qing China". Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 3 (1): 25–26. ISSN 1934-7227.