Aisin Gioro

Aisin Gioro was the Manchu ruling clan of the Later Jin dynasty (1616–1636), the Qing dynasty (1636–1912) and, nominally, Manchukuo (1932–1945). The House of Aisin Gioro ruled China proper from 1644 until the Xinhai Revolution of 1911–1912, which established a republican government in its place. The word aisin means gold in the Manchu language, and "gioro" is the name of the Aisin Gioro's ancestral home in present-day Yilan, Heilongjiang Province. In Manchu custom, families are identified first by their hala (哈拉), i.e. their family or clan name, and then by mukūn (穆昆), the more detailed classification, typically referring to individual families. In the case of Aisin Gioro, Aisin is the mukūn, and Gioro is the hala. Other members of the Gioro clan include Irgen Gioro (伊爾根覺羅), Šušu Gioro (舒舒覺羅) and Sirin Gioro (西林覺羅).

| Aisin Gioro ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ ᡤᡳᠣᡵᠣ | |

|---|---|

| Imperial House | |

| |

| Parent house | Qing dynasty |

| Country | Later Jin |

| Founded | 1616 |

| Founder | Nurhaci |

| Current head | Jin Yuzhang[1] |

| Final ruler | Puyi |

| Titles |

|

| Style(s) | "His/Her Imperial Majesty" |

| Estate(s) | Forbidden City (Beijing) Summer Palace (Beijing) Old Summer Palace (Beijing) Mukden Palace (Shenyang) Chengde Mountain Resort (Chengde) |

| Deposition | 1912 |

| Aisin Gioro | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 愛新覺羅 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 爱新觉罗 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||

| Manchu script | ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ ᡤᡳᠣᡵᠣ | ||||||

The Jin dynasty (jin means gold in Chinese) of the Jurchens, ancestors of the Manchus, was known as aisin gurun, and the Qing dynasty was initially named (![]()

Family generation names

Before the founding of the Qing dynasty, the naming of children in the Aisin Gioro clan was essentially arbitrary and followed no particular rules. The Manchu people originally did not use generation names before they moved into China proper; prior to the Shunzhi era, children of the imperial clan were given only a Manchu name, for example Dorgon.[2][3]

After taking control of China, however, the family gradually incorporated Han Chinese naming conventions.[4][5] During the reign of the Kangxi Emperor, all of the emperor's sons were to be named with a generation prefix preceding the given name. There were three characters initially used, Cheng (承), Bao (保) and Chang (長), before finally settling on Yin (胤) over a decade into the Kangxi era. The generation prefix of the Yongzheng Emperor's sons switched from Fu (福) to Hong (弘). Following the Yongzheng Emperor, the Qianlong Emperor decreed that all subsequent male offspring would have a generation prefix placed in their name according to a "generation poem", for which he composed the first four characters, Yong Mian Yi Zai (永綿奕載). Moreover, direct descendants of the emperor will often share a similar radical or meaning in the final character. A common radical was shared in the second character of the first name of princes who were in line to the throne, however, princes who were not in line to the throne did not necessarily share the radical in their name.[6] In one case, the Yongzheng Emperor changed the generation code of his brothers as a way of keeping his own name unique. Such practices apparently ceased to exist after the Daoguang era.

List of generation prefixes

The latest additions to the list were the last 12 characters, taken from a "generation poem" composed by Puyi in 1938.

| Order | Generation prefix | Radical code | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yongzheng Emperor | Yin (胤; yìn), Yun (允; yǔn) | Shi (示; shì) | Yinzhen, Yunreng, Yunsi, Yunxiang, Yunti |

| Qianlong Emperor | Hong (弘; hóng) | Ri (日; rì) | Hongli, Hongzhou |

| Jiaqing Emperor | Yong (永/顒; yǒng) | Yu (玉; yù) | Yongyan, Yongqi |

| Daoguang Emperor | Mian (綿; mián), Min (旻; mǐn) | Xin (心; xīn) | Minning, Mianyu |

| Xianfeng Emperor | Yi (奕; yì) | Yan (言; yán) | Yizhu, Yicong, Yixin, Yixuan, Yikuang |

| Tongzhi Emperor / Guangxu Emperor | Zai (載; zài/zǎi) | Shui (水; shuǐ) | Zaixun, Zaichun, Zaitian, Zaifeng, Zaitao, Zaiyi, Zaixun |

| Xuantong Emperor | Pu (溥; pǔ) | Ren (人; rén) | Puyi, Pujie, Puren, Puru |

| N/A | Yu (毓; yù) | Shan (山; shān) | Yuzhan, Yuyan |

| Heng (恆; héng) | Jin (金; jīn) | Hengxu | |

| Qi (啟; qǐ) | Qicong, Qigong | ||

| Dao (焘; dào) | |||

| Kai (闓; kǎi) | |||

| Zeng (增; zēng) | |||

| Qi (祺; qí) | |||

| Jing (敬; jìng) | |||

| Zhi (志; zhì) | |||

| Kai (開; kāi) | |||

| Rui (瑞; ruì) | |||

| Xi (錫; xī) | |||

| Ying (英; yīng) | |||

| Yuan (源; yuán) | |||

| Sheng (盛; shèng) | |||

| Zheng (正; zhèng) | |||

| Zhao (兆; zhào) | |||

| Mao (懋; mào) | |||

| Xiang (祥; xiáng) |

Origins

The Aisin Gioro clan, as a Manchu clan, claimed descent from the Jurchen people, who founded the Jin dynasty nearly five centuries earlier under the Wanyan clan. However, the Aisin Gioro and Wanyan clans are unrelated.[7] It was explicitly said "we are not the scions of the previous Jin emperors." by the Manchu leader Huangtaiji[8] to the Ming.[9]

The Aisin Gioro claimed that their progenitor, Bukūri Yongšon[10] (布庫里雍順), was conceived from a virgin birth. According to the legend, three heavenly maidens, namely Enggulen (恩古倫), Jenggulen (正古倫) and Fekulen (佛庫倫), were bathing at a lake called Bulhūri Omo near the Changbai Mountains. A magpie dropped a piece of red fruit near Fekulen, who ate it. She then became pregnant with Bukūri Yongšon.

The Aisin Gioro also claimed descent from Mentemu of the Odoli clan, who served as chieftains of the Jianzhou Jurchens.

The Jianzhou Jurchen originate partially from the Huligai who were classified by the Liao dynasty as a separate ethnicity from the Jurchen people who founded the Jin dynasty and were classified as separate from Jurchens during the Yuan dynasty. Their home was in the lower reaches of the Songhuajiang river and Mudanjiang. The Huligai later moved west and became a major component of the Jianzhou Jurchens led by Mentemu during the Ming dynasty, and the Jianzhou Jurchens later became Manchus. The Jurchens during the Ming dynasty lived in Jilin. It was in the Ming dynasty the term Jurchen was expanded and referred to a wide variety of different peoples in Heilongjiang. The Aisin Gioro are not the same Jurchens as the ones who founded the Jin.[11]

The Taowen, Huligai, and Wodolian Jurchen tribes lived in the area of Heilongjiang in Yilan during the Yuan dynasty when it was part of Liaoyang province and governed as a circuit. These tribes became the Jianzhou Jurchens in the Ming dynasty and the Taowen and Wodolian were mostly real Jurchens. In the Jin dynasy, the Jin Jurchens did not regard themselves as the same ethnicity as the Hurka people who became the Huligai. Uriangqa was used as a name in the 1300s by Jurchen migrants in Korea from Ilantumen because the Uriangqa influenced the people at Ilantumen.[12][13][10] Bokujiang, Tuowulian, Woduolian, Huligai, Taowan separately made up 10,000 households and were the divisions used by the Yuan dynasty to govern the people along the Wusuli river and Songhua area.[14][15] In the Jin dynasty the Shangjing route (上京路) governed the Huligai.[16] A Huligai route was created as well by the Jin.[17][18][19][20]

When the Jurchens were reorganized by Nurhaci into the Eight Banners, many Manchu clans were artificially created as a group of unrelated people founded a new Manchu clan (mukun) using a geographic origin name such as a toponym for their hala (clan name).[21] The irregularities over Jurchen and Manchu clan origin led to the Qing trying to document and systemize the creation of histories for Manchu clans, including manufacturing an entire legend around the origin of the Aisin Gioro clan by taking mythology from the northeast.[22]

Expansion under Nurhaci and Hong Taiji

Under Nurhaci and his son Hong Taiji, the Aisin Gioro clan of the Jianzhou tribe won hegemony among the rival Jurchen tribes of the northeast, then through warfare and alliances extended its control into Inner Mongolia. Nurhachi created large, permanent civil-military units called "banners" to replace the small hunting groups used in his early campaigns. A banner was composed of smaller companies; it included some 7,500 warriors and their households, including slaves, under the command of a chieftain. Each banner was identified by a coloured flag that was yellow, white, blue, or red, either plain or with a border design. Originally there were four, then eight, Manchu banners; new banners were created as the Manchu conquered new regions, and eventually there were Manchu, Mongol, and Chinese banners, eight for each ethnic group. By 1648, less than one-sixth of the bannermen were actually of Manchu ancestry. The Manchu conquest of the Ming dynasty was thus achieved with a multiethnic army led by Manchu nobles and Han Chinese generals. Han Chinese soldiers were organised into the Army of the Green Standard, which became a sort of imperial constabulary force posted throughout China and on the frontiers.

The change of the name from Jurchen to Manchu was made to hide the fact that the ancestors of the Manchus, the Jianzhou Jurchens, were ruled by the Chinese.[23][24][25] The Qing dynasty carefully hid the 2 original editions of the books of "Qing Taizu Wu Huangdi Shilu" and the "Manzhou Shilu Tu" (Taizu Shilu Tu) in the Qing palace, forbidden from public view because they showed that the Manchu Aisin Gioro family had been ruled by the Ming dynasty.[26][27] In the Ming period, the Koreans of Joseon referred to the Jurchen inhabited lands north of the Korean peninsula, above the rivers Yalu and Tumen to be part of Ming China, as the "superior country" (sangguk) which they called Ming China.[28] The Qing deliberately excluded references and information that showed the Jurchens (Manchus) as subservient to the Ming dynasty, from the History of Ming to hide their former subservient relationship to the Ming. The Veritable Records of the Ming were not used to source content on Jurchens during Ming rule in the History of Ming because of this.[29] This historical revisionism helped remove the accusation of rebellion from the Qing ruling family refusing to mention in the Mingshi the fact that the Qing founders were Ming China's subjects.[30] The Qing Yongzheng Emperor attempted to rewrite the historical record and claim that the Aisin Gioro were never subjects of past dynasties and empires trying to cast Nurhaci's acceptance of Ming titles like Dragon Tiger General (longhu jiangjun 龍虎將軍) by claiming he accepted to "please Heaven".[31]

Intermarriage and political alliances

The Qing emperors arranged marriages between Aisin Gioro noblewomen and outsiders to create political marriage alliances. During the Manchu conquest of the Ming Empire, the Manchu rulers offered to marry their princesses to Han Chinese military officers who served the Ming Empire as a means of inducing these officers into surrendering or defecting to their side. Aisin Gioro princesses were also married to Mongol princes, for the purpose of forming alliances between the Manchus and Mongol tribes.[32]

The Manchus successfully induced one Han Chinese general, Li Yongfang (李永芳), into defecting to their side by offering him a position in the Manchu banners. Li Yongfang also married the daughter of Abatai, a son of the Qing dynasty's founder Nurhaci. Many more Han Chinese abandoned their posts in the Ming Empire and defected to the Manchu side.[33] There were over 1,000 marriages between Han Chinese men and Manchu women in 1632 – due to a proposal by Yoto (岳托), a nephew of the Manchu emperor Hong Taiji.[34] Hong Taiji believed that intermarriage between Han Chinese and Manchus could help to eliminate ethnic conflicts in areas already occupied by the Manchus, as well as help the Han Chinese forget their ancestral roots more easily.[35]

Manchu noblewomen were also married to Han Chinese men who surrendered or defected to the Manchu side.[36] Aisin Gioro women were married to the sons of the Han Chinese generals Sun Sike (孫思克), Geng Jimao, Shang Kexi and Wu Sangui.[37] The e'fu (額駙) rank was given to husbands of Manchu princesses. Geng Zhongming, a Han bannerman, was awarded the title "Prince Jingnan", while his grandsons Geng Jingzhong, Geng Zhaozhong (耿昭忠) and Geng Juzhong (耿聚忠) married Hooge's daughter, Abatai's granddaughter, and Yolo's daughter respectively.[38] Sun Sike's son, Sun Cheng'en (孫承恩), married the Kangxi Emperor's fourth daughter, Heshuo Princess Quejing (和硕悫靖公主).[37]

Imperial Duke Who Assists the State (宗室輔國公) Aisin Gioro Suyan's (蘇燕) daughter was married to Han Chinese Banner General Nian Gengyao.[39][40][41]

Genetics

Haplogroup C3b2b1*-M401(xF5483)[42][43][44] has been identified as a possible marker of the Aisin Gioro and is found in ten different ethnic minorities in northern China, but completely absent from Han Chinese.[45][46]

Notable Aisin Gioros

Emperors

- Nurhaci (1559–1626), founder of the Qing dynasty

- Hong Taiji (1592–1643), Nurhaci's eighth son

- Fulin (1638–1661), the Shunzhi Emperor, Hong Taiji's ninth son

- Xuanye (1654–1722), the Kangxi Emperor, the Shunzhi Emperor's third son

- Yinzhen (1678–1735), the Yongzheng Emperor, the Kangxi Emperor's fourth son

- Hongli (1711–1799), the Qianlong Emperor, the Yongzheng Emperor's fourth son

- Yongyan (1760–1820), the Jiaqing Emperor, the Qianlong Emperor's 15th son

- Minning (1782–1850), the Daoguang Emperor, the Jiaqing Emperor's second son

- Yizhu (1831–1861), the Xianfeng Emperor, the Daoguang Emperor's fourth son

- Zaichun (1856–1875), the Tongzhi Emperor, the Xianfeng Emperor's first son

- Zaitian (1871–1908), the Guangxu Emperor, Yixuan's second son, symbolically adopted as the Xianfeng Emperor's son

- Puyi (1906–1967), the Xuantong Emperor, Zaifeng's first son, symbolically adopted as the Tongzhi Emperor's son

Iron-cap princes and their descendants

According to Qing dynasty imperial tradition, the sons of princes do not automatically inherit their fathers' titles in the same rank as their fathers. For example, Yongqi held the title "Prince Rong of the First Rank", but when his title was passed on to his son, Mianyi, it became "Prince Rong of the Second Rank". In other words, the title gets diminished by one rank as it is passed down to each subsequent generation, but generally to no lower than the rank of kesi-be tuwakiyara gurun-de aisilara gung (second class imperial duke). However, there were 12 princes who were awarded the shi xi wang ti (perpetual heritability, a.k.a. "iron-cap") privilege, which meant that their titles can be passed on to subsequent generations without the downgrading effect.

The 12 "iron-cap" princely peerages are listed as follows. Some of them were renamed at different points in time, hence they had multiple names.

- Prince Zheng / Prince Jian, the line of Jirgalang (1599–1655), descendant of Taksi

- Prince Li / Prince Xun / Prince Kang, the line of Daišan (1583–1648), descendant of Nurhaci

- Prince Keqin / Prince Cheng / Prince Ping / Prince Yanxi, the line of Yoto (1599–1639), descendant of Nurhaci

- Prince Shuncheng, the line of Lekdehun (1619–1652), descendant of Nurhaci

- Prince Keqin / Prince Cheng / Prince Ping / Prince Yanxi, the line of Yoto (1599–1639), descendant of Nurhaci

- Prince Rui, the line of Dorgon (1612–1650), descendant of Nurhaci

- Prince Yu, the line of Dodo (1614–1649), descendant of Nurhaci

- Prince Su / Prince Xian, the line of Hooge (1609–1648), descendant of Hong Taiji

- Prince Chengze / Prince Zhuang, the line of Šose (1629–1655), descendant of Hong Taiji

- Prince Yi, the line of Yinxiang (1686–1730), descendant of Kangxi Emperor

- Prince Qing, the line of Yonglin (1766–1820), descendant of Qianlong Emperor

- Prince Gong, the line of Yixin (1833–1898), descendant of Daoguang Emperor

- Prince Chun, the line of Yixuan (1840–1891), descendant of Daoguang Emperor

Prominent political figures

- Daišan (1583-1648), Nurhaci's second son, participated in the Qing conquest of the Ming

- Jirgalang (1599–1655), Nurhaci's nephew, co-regent with Dorgon during the Shunzhi Emperor's early reign

- Ajige (1605–1651), Nurhaci's 12th son, participated in the Qing conquest of the Ming

- Dorgon (1612–1650), Nurhaci's 14th son, Prince-Regent and de facto ruler during the Shunzhi Emperor's early reign

- Dodo (1614–1649), Nurhaci's 15th son, participated in the Qing conquest of the Ming

- Yinsi (1681–1726), the Kangxi Emperor's eighth son, Yinzhen's competitor for the succession, expelled from the Aisin Gioro clan later

- Yinxiang (1686–1730), the Kangxi Emperor's 13th son, Yinzhen's ally

- Yinti (1688–1756), the Kangxi Emperor's 14th son, Yinzhen's competitor for the succession, purported rightful heir to the throne

- Duanhua (1807–1861), descendant of Jirgalang, regent for the Tongzhi Emperor, ousted from power in the Xinyou Coup in 1861

- Sushun (1816–1861), Duanhua's brother, regent for the Tongzhi Emperor, ousted from power in the Xinyou Coup in 1861

- Zaiyuan (1816–1861), descendant of Yinxiang, regent for the Tongzhi Emperor, ousted from power in the Xinyou Coup in 1861

- Yixin (1833–1898), the Daoguang Emperor's sixth son, Prince-Regent during the Tongzhi Emperor's reign

- Yikuang (1838–1917), descendant of Yonglin, Prime Minister of the Imperial Cabinet

- Yixuan (1840–1891), the Daoguang Emperor's seventh son, the Guangxu Emperor's biological father

- Zaiyi (1856–1922), Yicong's son, Boxer Rebellion leader

- Zaize (1876–1929), a sixth-generation descendant of the Kangxi Emperor, Finance Minister and Salt Policy Minister in the Imperial Cabinet

- Zaizhen (1876–1947), Yikuang's son, court minister

- Zaifeng (1883–1951), Yixuan's son, Puyi's biological father, Prince-Regent during Puyi's reign

- Zaixun (1885–1949), Yixuan's sixth son, Navy Minister in the Imperial Cabinet

20th century – present

- Pujin (溥伒; 1893–1966), better known as Pu Xuezhai (溥雪齋), guqin player and Chinese painting artist, grandson of Yicong (Prince Dun)

- Puru (1896–1963), Taiwanese artist and calligrapher, grandson of Yixin (Prince Gong)

- Jin Guangping (1899–1966), born Aisin Gioro Hengxu, scholar of the Jurchen and Khitan languages

- Yoshiko Kawashima (1907–1948), born Aisin Gioro Xianyu, a spy for the Japanese Empire during the Sino-Japanese War

- Pujie (1907–1994), Puyi's brother, member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, nominal head of the Aisin Gioro clan from 1967–1994

- Qigong (1912–2005), artist and calligrapher, descended from the Prince He peerage

- Yuyan (1918–1997), calligrapher, distant nephew of Puyi

- Jin Qicong (1918–2004), Jin Guangping's son, historian and scholar of the Jurchen and Manchu languages

- Jin Moyu (1918–2014), born Aisin Gioro Xianqi, Yoshiko Kawashima's younger sister, educator

- Jin Youzhi (1918–2015), born Aisin Gioro Puren, Puyi's half-brother, nominal head of the Aisin Gioro clan from 1994–2015

- Aisin Gioro Yuhuan (1929–2003), sanxian player and Chinese painting artist

- Jin Yuzhang (born 1942), Jin Youzhi's son, governor of Beijing's Chongwen District, nominal head of the Aisin Gioro clan since 2015

- Jin Pucong (born 1956), Taiwanese politician, allegedly[47] descended from the Aisin Gioro clan

- Aisin-Gioro Ulhicun (born 1958), Jin Qicong's daughter, historian and scholar of the Jurchen, Khitan and Manchu languages

- Zhao Junzhe (born 1979), football player, descended from Boolungga, the fifth brother of Nurhaci's grandfather Giocangga

- Ariel Aisin-Gioro (born 1983), actress

Gallery

- Images

Nurhaci on his throne

Nurhaci on his throne Nurhaci

Nurhaci- Nurhaci

Nurhaci

Nurhaci Nurhaci

Nurhaci

Zaitao in the United States

Zaitao in the United States Yixin (Prince Gong)

Yixin (Prince Gong)%2C_born_Italy_-_Prince_Kung_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Yixin (Prince Gong)

Yixin (Prince Gong) Zaixun (Prince Rui) in the United States

Zaixun (Prince Rui) in the United States- Zaixun (Prince Rui) in the United States

- Zaixun (Prince Rui)

Yixuan (Prince Chun)

Yixuan (Prince Chun) Yixuan (Prince Chun) and his wife

Yixuan (Prince Chun) and his wife- Yixuan (Prince Chun) with Li Hongzhang and Shanqing

Yixuan (Prince Chun)

Yixuan (Prince Chun)

Shanqi (Prince Su)

Shanqi (Prince Su) Shanqi (Prince Su)

Shanqi (Prince Su).jpg) Zaifeng (Prince Chun)

Zaifeng (Prince Chun) Zaifeng (Prince Chun)

Zaifeng (Prince Chun) Zaifeng (Prince Chun) and his family

Zaifeng (Prince Chun) and his family

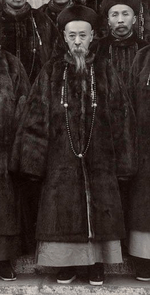

Yikuang (Prince Qing)

Yikuang (Prince Qing)

See also

References

- Heir to China's throne celebrates a modest life, The Age, November 27, 2004

- Edward J. M. Rhoads (2001). Manchus & Han: ethnic relations and political power in late Qing and early republican China, 1861-1928 (reprint, illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.

In the beginning, among the first couple of generations, Manchu men had polysyllabic personal names (e.g., Nurhaci) that in their native language may have been meaningful but when transliterated by sound into Chinese characters were gibberish; furthermore, they did not arrange their personal names in generational order, as Han often did.

- Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 243.

Manchu naming practices also differed when it came to naming the children of the same generation. Chinese practice, at least among elites, typically called for all children of the same lineage and same generation to share the same first character of the given name. All the brothers and cousins (or sisters and cousins) of the same generation would be identified by this character (sometimes called beifen yongzi), which greatly simplified the determination of re

- Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 244.

lationships within the linage. The Manchus were not so careful about this sort of thing... The Chinese practice of using the same first character for the given names of children of same generation was initially adopted during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. The children of Kangxi all sported the same prefix-character, yin (written "in" in Manchu), and every generation afterward was marked by the same initial character (or, in Manchu, the same initial sounds) in the given name. While some Manchu families followed suit, many others did not, or did so inconsistently: for example, the brother of an early-eighteenth-century general, Erentei, was named Torio, while the Xi'an general Cangseli named his son Cangyung, using the same sound, "cang" ("chang" in Chinese), for his and the following generation.

- Edward J. M. Rhoads (2001). Manchus & Han: ethnic relations and political power in late Qing and early republican China, 1861-1928 (reprint, illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 55.

With the imperial clan itself taking the lead, Manchus started to shorten their personal names to disyllabic ones (e.g., Yinzhen, for the future Yongzheng emperor), to adopt names that were meaningful and felicitous in Chinese, and to assign names on a generaltional basis. By the time of the Guangxu emperor (r. 1875-1908), all the males of his generation in the imperial clan had the character zai in their personal names, such as Zaitian (the emperor), Zaifeng (1883-1952; his brother and future regent), and Zaizhen (1876-1948; his cousin). By contrast, the previous generation had used the character yi (e.g., Yikuang, Yixin, and Yihuan), while the following generation used the character pu (e.g., the future Xuantong emperor Puyi [1906-67] and his brother Pujie [1907-94]).

- Edward J. M. Rhoads (2001). Manchus & Han: ethnic relations and political power in late Qing and early republican China, 1861-1928 (reprint, illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.

In a further refinement of the generational principle, the second character in the personal name of each person in the direct line of succession contained a radical that distinguished these name from all others of their generation in the imperial clan. Thus, the tian character in "Zaiyian" and the feng character in "Zaifeng" shared the "water" radical; hiweverm the zhen in "Zaizhen" (written with the "hand" radical) did not, because as the son of Yikuang (Prince Qing), Zaizhen was not in the direct line of succession.

- 滿洲源流考 Qing ding Man Zhou Yuan Liu Kao, 本朝者謂雖與大金俱在東方而非其同部則所見殊小我朝得姓曰愛新覺羅氏國語謂金曰愛新可為金源同派之証盖我朝在大金時未嘗非完顔氏之服屬猶之完顔 氏在今日皆為我朝之臣

- Stevan Harrell (15 January 2013). Cultural Encounters on China's Ethnic Frontiers. University of Washington Press. pp. 190–. ISBN 978-0-295-80408-8.

- Nicholas Thomas; Caroline Humphrey (1996). Shamanism, History, and the State. University of Michigan Press. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-0-472-08401-2.

- Pamela Kyle Crossley (15 February 2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 198–. ISBN 978-0-520-92884-8.

- "后金朝介绍:后金的祖先是谁?什么族人?". 中国历史_历史人物大全_中国历史朝代_历史故事大全- 历史之家网. 2016-09-01. Archived from the original on 2018-05-11.

- Chʻing-shih Wen-tʻi. Chʻing-shih wen-tʻi. 1983. p. 33.

- Ch'ing-shih Wen-t'i. Ch'ing-shih wen-t'i. 1983. p. 33.

- Yin Ma (1989). China's minority nationalities. Foreign Languages Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8351-1952-8.

- Tadeusz Dmochowski (2001). Rosyjsko-chińskie stosunki polityczne: XVII-XIX w. Wydawn. Univ. p. 81. ISBN 978-83-7017-986-1.

- ı̃Ư̄Ư̆ʺ̄ø̄ʻ̄̌: The Liao dynasty and Northern Song dynasty period, the Jin dynasty and Southern Song dynasty period. Volume 6 of ı̃Ư̄Ư̆ʺ̄ø̄ʻ̄̌, ʻ̈Ư̄œ♭̌Þ. ̄ʻ̄̄ð ̇ Þ̇.

- 黑龙江省交通厅 (1999). 中国交通五十年成就: 黑龙江卷. 人民交通出版社. p. 22.

- China Archaeology & Art Digest. Art Text (HK) Pty Limited. 1999. p. 205.

- Zhu, Ruixi; Zhang, Bangwei; Liu, Fusheng; Cai, Chongbang; Wang, Zengyu (22 December 2016). A Social History of Medieval China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 524–. ISBN 978-1-107-16786-5.

- Sergeĭ Leonidovich Tikhvinskiĭ; Leonard Sergeevich Perelomov (1981). China and Her Neighbours, from Ancient Times to the Middle Ages: A Collection of Essays. Progress Publishers. p. 201.

- Sneath, David (2007). The Headless State: Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, and Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner Asia (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0231511674.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1991). Orphan Warriors: Three Manchu Generations and the End of the Qing World (illustrated, reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0691008779.

- Hummel, Arthur W., ed. (2010). "Abahai". Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, 1644-1912 (2 vols) (reprint ed.). Global Oriental. p. 2. ISBN 978-9004218017. Via Dartmouth.edu

- Grossnick, Roy A. (1972). Early Manchu Recruitment of Chinese Scholar-officials. University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 10.

- Till, Barry (2004). The Manchu era (1644-1912): arts of China's last imperial dynasty. Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. p. 5.

- Hummel, Arthur W., ed. (2010). "Nurhaci". Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, 1644-1912 (2 vols) (reprint ed.). Global Oriental. p. 598. ISBN 978-9004218017. Via Dartmouth.edu

- The Augustan, Volumes 17-20. Augustan Society. 1975. p. 34.

- Kim, Sun Joo (2011). The Northern Region of Korea: History, Identity, and Culture. University of Washington Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0295802176.

- Smith, Richard J. (2015). The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 216. ISBN 978-1442221949.

- Fryslie, Matthew (2001). The historian's castrated slave: the textual eunuch and the creation of historical identity in the Ming history. University of Michigan. p. 219.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2002). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. pp. 303–4. ISBN 0520234243.

- Anne Walthall, ed. (2008). Servants of the dynasty: palace women in world history. Volume 7 of The California world history library (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 148. ISBN 9780520254435. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppzvr.

Whereas the emperor and princes chose wives or concubines from the banner population through the drafts, imperial daughters were married to Mongol princes, Manchu aristocrats, or, on some occasions, Chinese high officials... To win the support and cooperation of Ming generals in Liaodong, Nurhaci gave them Aisin Gioro women as wives. In 1618, before he attacked Fushun city, he promised the Ming general defending the city a woman from the Aisin Gioro clan in marriage if he surrendered. After the general surrendered, Nurhaci gave him one of his granddaughters. Later the general joined the Chinese banner.

- Frederic E. Wakeman, Jr. (1977). The fall of imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-02-933680-9.

Chinese elements had joined the Manchu armies as early as 1618 when the Ming commander Li Yung-fang surrendered at Fu-shun. Li was made a banner general, was given gifts of slaves and serfs, and was betrothed to a young woman of the Aisin Gioro clan. Although Li's surrender at the time was exceptional, his integration into the Manchu elite was only the first of many such defections by border generals and their subordinates, who shaved their heads and accepted Manchu customs. It was upon these prisoners, then, that Abahai relied to form new military units to fight their former master, the Ming Emperor.

- Anne Walthall, ed. (2008). Servants of the dynasty: palace women in world history. Volume 7 of The California world history library (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 148. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppzvr.

In 1632, Hongtaiji accepted the suggestion of Prince Yoto, his nephew, and assigned one thousand Manchu women to surrendered Chinese officials and generals for them to marry. He also classified these Chinese into groups by rank and gave them wives accordingly. "First-rank officials were given Manchu princes' daughters as wives; second rank officials were given Manchu ministers' daughters as wives."

- Anne Walthall, ed. (2008). Servants of the dynasty: palace women in world history. Volume 7 of The California world history library (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 148. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppzvr.

Hongtaiji believed that only through intermarrige between Chinese and Manchus would he be able to eliminate ethnic conflicts in the areas he conquered; and "since the Chinese generals and Manchu women lived together and ate together, it would help these surrendered generals to forget their motherland"

- Anne Walthall, ed. (2008). Servants of the dynasty: palace women in world history. Volume 7 of The California world history library (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 148. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppzvr.

During their first years in China, the Manchu rulers continued to give imperial daughters to Chinese high officials. These included the sons of the Three Feudatories—the Ming defectors rewarded with large and almost autonomous fiefs in the south.

- Rubie Sharon Watson; Patricia Buckley Ebrey, eds. (1991). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7.

- Frederic E. Wakeman, Jr. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 1017–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- 唐博 (2010). 清朝權臣回憶錄. 遠流出版. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-957-32-6691-4.

- 施樹祿 (17 May 2012). 世界歷史戰事傳奇. 華志文化. pp. 198–. ISBN 978-986-5936-00-6.

- "清代第一战神是谁? 年羹尧和岳钟琪谁的成就更高?". 历史网. 2016-03-07. Archived from the original on 2016-08-28.

- Wei, Ryan Lan-Hai; Yan, Shi; Yu, Ge; Huang, Yun-Zhi (November 2016). "Genetic trail for the early migrations of Aisin Gioro, the imperial house of the Qing dynasty". Journal of Human Genetics. 62 (3): 407–411. doi:10.1038/jhg.2016.142. PMID 27853133.

- Yan, Shi; Tachibana, Harumasa; Wei, Lan-Hai; Yu, Ge; Wen, Shao-Qing; Wang, Chuan-Chao (June 2015). "Y chromosome of Aisin Gioro, the imperial house of the Qing dynasty". Journal of Human Genetics. 60 (6): 295–8. arXiv:1412.6274. doi:10.1038/jhg.2015.28. PMID 25833470.

- "Did you know DNA was used to uncover the origin of the House of Aisin Gioro?". Did You Know DNA...

- Xue, Yali; Zerjal, Tatiana; Bao, Weidong; Zhu, Suling; Lim, Si-Keun; Shu, Qunfang; Xu, Jiujin; Du, Ruofu; Fu, Songbin; Li, Pu; Yang, Huanming; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2005). "Recent Spread of a Y-Chromosomal Lineage in Northern China and Mongolia" (PDF). The American Journal of Human Genetics. 77 (6): 1112–1116. doi:10.1086/498583. PMC 1285168. PMID 16380921. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- "Asian Ancestry based on Studies of Y-DNA Variation: Part 3. Recent demographics and ancestry of the male East Asians – Empires and Dynasties". Genebase Tutorials. Archived from the original on November 25, 2013.

- 曹長青 (2009-12-14). 金溥聰是不是溥儀的堂弟? [King Pu-tsung is not the cousin of Henry Puyi?] (in Chinese). Taiwan: Liberty Times. Archived from the original on 2009-12-17.

External links