Makassar

Makassar (Indonesian pronunciation: [maˈkassar] (![]()

Makassar | |

|---|---|

| City of Makassar Kota Makassar | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Makassarese | ᨀᨚᨈ ᨆᨀᨔᨑ |

.jpg)   From top, left to right: Makassar skyline, Fort Rotterdam, Makassar Old Harbour, Sahid Jaya Hotel, and floating mosque of Amirul Mukminin, Trans Studio Street | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "City of Daeng"; "Ujung Pandang" | |

| Motto(s): Sekali Layar Terkembang Pantang Biduk Surut Ke Pantai | |

| Coordinates: 5°8′S 119°25′E | |

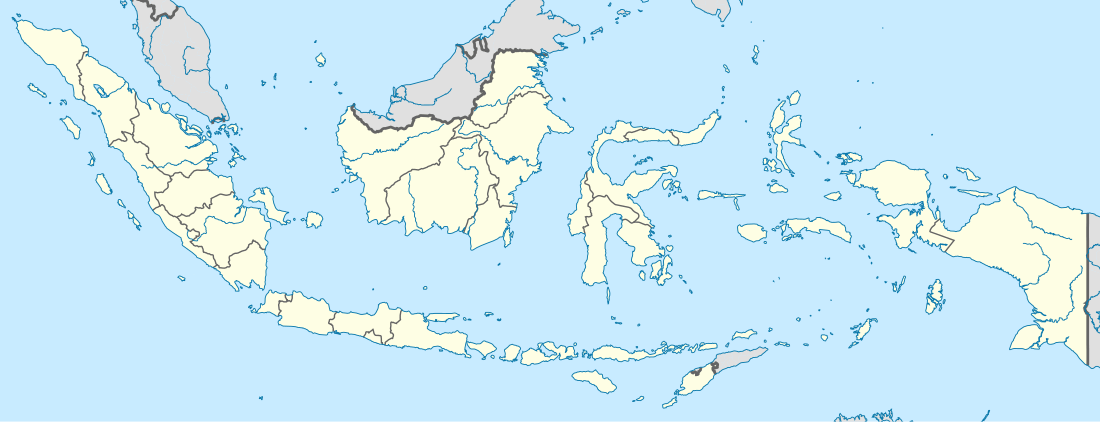

| Country | |

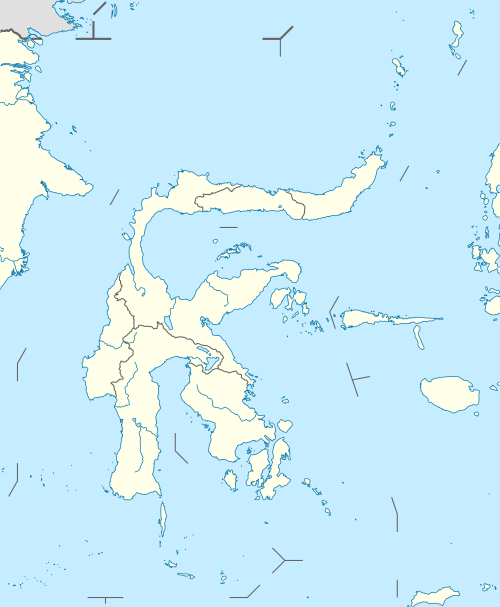

| Region | Sulawesi |

| Province | |

| Founded | 9 November 1607 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rudy Djamaluddin (officials) |

| Area | |

| • City | 199.3 km2 (77.0 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,689.89 km2 (1,038.57 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0–25 m (0–82 ft) |

| Population (2019 estimated[1]) | |

| • City | 1,508,154 |

| • Density | 7,600/km2 (20,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,696,242 |

| • Metro density | 1,000/km2 (2,600/sq mi) |

| 2017 decennial census | |

| Demonym(s) | Makassarese |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (Indonesia Central Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+8 (not observed) |

| Area code | (+62) 411 |

| Vehicle registration | DD |

| Website | |

Throughout its history, Makassar has been an important trading port, hosting the centre of the Gowa Sultanate and a Portuguese naval base before its conquest by the Dutch East India Company in the 17th century. It remained an important port in the Dutch East Indies, serving Eastern Indonesian regions with Makassarese fishers going as far south as the Australian coast. For a brief period after Indonesian independence, Makassar became the capital of the State of East Indonesia, during which an uprising occurred.

The city's area is 199.3 square kilometres (77.0 sq mi), and it had a population of around 1.5 million in 2019[2][4][5] within Makassar City's 15 districts. Its official metropolitan area, known as Mamminasata, with 17 additional districts of neighbouring regencies, covers an area of 2,548 square kilometres (984 sq mi) and had a population of around 2,696,242 according to 2019 official estimates.[6] According to the National Development Planning Agency, Makassar is one of the four main central cities of Indonesia, alongside Medan, Jakarta, and Surabaya.[7][8] According to Bank Indonesia, Makassar has the second-highest commercial property values in Indonesia, after Greater Jakarta.[9] At present, Makassar has experienced a very rapid economic growth beyond the average growth rate of Indonesia.

History

The trade in spices figured prominently in the history of Sulawesi, which involved frequent struggles between rival native and foreign powers for control of the lucrative trade during the pre-colonial and colonial period when spices from the region were in high demand in the West. Much of South Sulawesi's early history was written in old texts that can be traced back to the 13th and 14th centuries.

Makassar is mentioned in the Nagarakretagama, a Javanese eulogy composed in 14th century during the reign of Majapahit king Hayam Wuruk. In the text, Makassar is mentioned as an island under Majapahit dominance, alongside Butun, Salaya and Banggawi.[10]

Makassarese Kingdom

The 9th King of Gowa Tumaparisi Kallonna (1512-1546) is described in the royal chronicle as the first Gowa ruler to ally with the nearby trade-oriented polity of Tallo, a partnership which endured throughout Makassar's apogee as an independent kingdom. The centre of the dual kingdom was at Sombaopu, near the then mouth of the Jeneberang River about 10 km south of the present city centre, where, where an international port and a fortress were gradually developed. First Malay traders (expelled from their Melaka metropolis by the Portuguese in 1511), then Portuguese from at least the 1540s, began to make this port their base for trading to the Spice Islands' (Maluku), further east.[11]

The growth of Dutch maritime power over the spice trade after 1600 made Makassar more vital as an alternative port open to all traders, as well as a source of rice to trade with rice-deficient Maluku. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) sought a monopoly of Malukan nutmeg and cloves and came close to succeeding at the expense of English, Portuguese and Muslims from the 1620s. The Makassar kings maintained a policy of free trade, insisting on the right of any visitor to do business in the city, and rejecting the attempts of the Dutch to establish a monopoly.[12]

Makassar depended mainly on the Muslim Malay and Catholic Portuguese sailors communities as its two crucial economic assets. However the English East India Company also established a post there in 1613, the Danish Company arrived in 1618, and Chinese, Spanish and Indian traders were all important. When the Dutch conquered Portuguese Melaka in 1641, Makassar became the most extensive Portuguese base in Southeast Asia. The Portuguese population had been in the hundreds but rose to several thousand, served by churches of the Franciscans, Dominicans and Jesuits as well as the regular clergy. By the 16th century, Makassar had become Sulawesi's principal port and centre of the powerful Gowa and Tallo sultanates which between them had a series of 11 fortresses and strongholds and a fortified sea wall that extended along the coast.[12] Portuguese rulers called the city Macáçar.

Makassar was very ably led in the first half of the 17th century when it effectively resisted Dutch pressure to close down its trade to Maluku and made allies rather than enemies of the neighbouring Bugis states. Karaeng Matoaya (c.1573-1636) was the ruler of Tallo from 1593, as well as Chancellor or Chief Minister (Tuma'bicara-butta) of the partner kingdom of Gowa. He managed the succession to the Gowa throne in 1593 of the 7-year-old boy later known as Sultan Alaud-din, and guided him through the acceptance of Islam in 1603, numerous modernizations in military and civil governance, and cordial relations with the foreign traders. The conversion of the citizens to Islam was followed by the first official Friday Prayer in the city, traditionally dated to 9 November 1607, which is celebrated today as the city's official anniversary.[13] John Jourdain called Makassar in his day "the kindest people in all the Indias to strangers".[14] Matoaya's eldest son succeeded him on the throne of Tallo, but as Chancellor, he had evidently groomed his brilliant second son, Karaeng Pattingalloang (1600–54), who exercised that position from 1639 until his death. Pattingalloang must have been partly educated by Portuguese, since as an adult he spoke Portuguese "as fluently as people from Lisbon itself", and avidly read all the books that came his way in Portuguese, Spanish or Latin. French Jesuit Alexandre de Rhodes described his passion for mathematics and astronomy, on which he pestered the priest endlessly, while even one of his Dutch adversaries conceded he was "a man of great knowledge, science and understanding."[15]

Dutch colonial period

After Pattingalloang's death in 1654, a new king of Gowa, Sultan Hasanuddin, rejected the alliance with Tallo by declaring he would be his own Chancellor. Conflicts within the kingdom quickly escalated, the Bugis rebelled under the leadership of Bone, and the Dutch VOC seized its long-awaited chance to conquer Makassar with the help of the Bugis (1667-9). Their first conquest in 1667 was the northern Makassar fort of Ujung Pandang, while in 1669 they conquered and destroyed Sombaopu in one of the greatest battles of 17th century Indonesia. The VOC moved the city centre northward, around the Ujung Pandang fort they rebuilt and renamed Fort Rotterdam. From this base, they managed to destroy the strongholds of the Sultan of Gowa, who was then forced to live on the outskirts of Makassar. Following the Java War (1825–30), Prince Diponegoro was exiled to Fort Rotterdam until his death in 1855.[16]

.svg.png)

After the arrival of the Dutch, there was an important Portuguese community, also called a bandel, that received the name of Borrobos.[18] Around 1660 the leader of this community, which today would be equivalent to a neighbourhood, was the Portuguese Francisco Vieira de Figueiredo.[19]

The character of this old trading centre changed as a walled city known as Vlaardingen grew. Gradually, in defiance of the Dutch, the Arabs, Malays and Buddhist returned to trade outside the fortress walls and were joined later by the Chinese.

The town again became a collecting point for the produce of eastern Indonesia – the copra, rattan, Pearls, trepang and sandalwood and the famous oil made from bado nuts used in Europe as men's hairdressing – hence the anti-macassars (embroidered cloths protecting the head-rests of upholstered chairs).

Although the Dutch controlled the coast, it was not until the early 20th century that they gained power over the southern interior through a series of treaties with local rulers. Meanwhile, Dutch missionaries converted many of the Toraja people to Christianity. By 1938, the population of Makassar had reached around 84,000 – a town described by writer Joseph Conrad as "the prettiest and perhaps, cleanest looking of all the towns in the islands".

In World War II the Makassar area was defended by approximately 1000 men of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army commanded by Colonel M. Vooren. He decided that he could not defend the coast, and was planning to fight a guerrilla war inland. The Japanese landed near Makassar on 9 February 1942. The defenders retreated but were soon overtaken and captured.[20]

After independence

In 1945, Indonesia proclaimed its Independence, and in 1946, Makassar became the capital of the State of East Indonesia, part of the United States of Indonesia.[21] In 1950, it was the site of fighting between pro-Federalist forces under Captain Abdul Assiz and Republican forces under Colonel Sunkono during the Makassar uprising.[22] By the 1950s, the population had increased to such a degree that many of the historic sites gave way to modern development, and today one needs to look very carefully to find the few remains of the city's once-grand history.

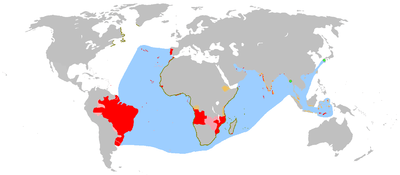

Connection with Australia

Makassar is also a significant fishing centre in Sulawesi. One of its major industries is the trepang (sea cucumber) industry. Trepang fishing brought the Makassan people into contact with Indigenous Australian peoples of northern Australia, long before European settlement (from 1788).

C. C. MacKnight in his 1976 work entitled Voyage to Marege: Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia has shown that they began frequenting the north of Australia around 1700 in search of trepang (sea-slug, sea cucumber, Beche-de-mer), an edible Holothurian. They left their waters during the Northwest Monsoon in December or January for what is now Arnhem Land, Marriage or Marega and the Kimberley region or Kayu Djawa. They returned home with the south-east trade winds in April.[23]

A fleet of between 24 and 26 Macassan perahus was seen in 1803 by French explorers under Nicolas Baudin on the Holothuria Banks in the Timor Sea. In February 1803, Matthew Flinders in the Investigator met six perahus with 20–25 men each on board and was told by the fleet's chief Pobasso, that there were 60 perahus then on the north Australian coast. They were fishing for trepang and appeared to have only a small compass as a navigation aid. In June 1818 Macassan trepang fishing was noted by Phillip Parker King in the vicinity of Port Essington in the Arafura Sea. In 1865 R.J. Sholl, then Government Resident for the British settlement at Camden Sound (near Augustus Island in the Kimberley region) observed seven 'Macassan' perahus with a total of around 300 men on board. He believed that they made kidnapping raids and ranged as far south as Roebuck Bay (later Broome) where 'quite a fleet' was seen around 1866. Sholl believed that they did not venture south into other areas such as Nickol Bay (where the European pearling industry commenced around 1865) due to the absence of trepang in those waters. The Macassan voyages appear to have ceased sometime in the late nineteenth century, and their place was taken by other sailors operating from elsewhere in the Indonesian archipelago.[24]

Economy

The city is southern Sulawesi's primary port, with regular domestic and international shipping connections. It is nationally famous as an essential port of call for the pinisi boats, sailing ships which are among the last in use for regular long-distance trade.

During the colonial era, the city was widely known as the namesake of Makassar oil, which it exported in substantial quantity. Makassar ebony is a warm black hue, streaked with tan or brown tones, and highly prized for use in making fine cabinetry and veneers.

Nowadays, as the largest city in Sulawesi Island and Eastern Indonesia, the city's economy depends highly on the service sector, which makes up approximately 70% of activity. Restaurant and hotel services are the most significant contributor (29.14%), followed by transportation and communication (14.86%), trading (14.86), and finance (10.58%). Industrial activity is the next most important after the service sector, with 21.34% of overall activity.[25]

Transportation

Makassar has a public transportation system called pete-pete. A pete-pete (known elsewhere in Indonesia as an angkot) is a minibus that has been modified to carry passengers. The route of Makassar's pete-petes is denoted by the letter on the windshield. Makassar is also known for its becak (pedicabs), which are smaller than the "becak" on the island of Java. In Makassar, people who drive pedicabs are called Daeng. In addition to becak and pete-pete, the city has a government-run bus system and taxis.

A bus rapid transit (BRT), which is known as "Trans Mamminasata" was started in 2014. It has some routes through Makassar to cities around Makassar region such as Maros, Takallar, and Gowa. Run by the Indonesian Transportation Department, each bus has 20 seats and space for 20 standing passengers.

A 35-kilometre monorail in the areas of Makassar, Maros Regency, Sungguminasa (Gowa Regency), and Takalar Regency (the Mamminasata region) was proposed in 2011, with operations commencing in 2014, at a predicted cost of Rp.4 trillion ($468 million). The memorandum of understanding was signed on 25 July 2011 by Makassar city, Maros Regency and Gowa Regency.[26][27] In 2014, the project was officially abandoned, citing insufficient ridership and a lack of financial feasibility.[28]

The city of Makassar, its outlying districts, and the South Sulawesi Province are served by Hasanuddin International Airport. The airport is located outside the Makassar city administration area, being situated in the nearby Maros Regency.

The city is served by Soekarno-Hatta Sea Port. In January 2012 it was announced that due to limited capacity of the current dock at Soekarno-Hatta sea port, it would be expanded to 150x30 square meters to avoid the need for at least two ships to queue every day.[29]

Administration and governance

The executive head of the city is the mayor, who is elected by direct vote for a period of five years. The mayor is assisted by a deputy mayor, who is also an elected official. There is a legislative assembly for the city, members of which are also elected for a period of five years. Makassar City is divided into 15 administrative districts and 153 urban villages. The districts are listed below with their areas and their populations at the 2010 Census,[30] and the latest (2019) official estimates:[5]

| Name | Area in km2 | Population Census 2010[30] | Population Estimate 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mariso | 1.82 | 56,313 | 60,499 |

| Mamajang | 2.25 | 59,133 | 61,452 |

| Tamalate | 20.21 | 169,890 | 205,541 |

| Rappocini | 9.23 | 151,357 | 170,121 |

| Makassar | 2.52 | 81,901 | 85,515 |

| Ujung Pandang | 2.63 | 27,206 | 29,054 |

| Wajo | 1.99 | 29,670 | 31,453 |

| Bontoala | 2.10 | 54,268 | 57,197 |

| Ujung Tanah | 5.94 | 46,771 | 35,534 |

| Sangkarang Islands | 5.83 | (a) | 14,531 |

| Tallo | 17.05 | 133,815 | 140,330 |

| Panukkukang | 24.14 | 141,524 | 149,664 |

| Manggala | 48.22 | 117,303 | 149,487 |

| Biringkanaya | 31.84 | 167,843 | 220,456 |

| Tamalanrea | 35.20 | 101,669 | 115,843 |

Note (a) The 2010 population of the Sangkarang Islands district is included in the figure for the Ujung Tanah district, from which it was cut out.

Geography

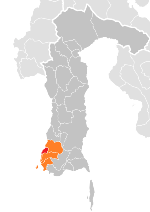

This official metropolitan area covers 2.689,89 km2 and had a population of 2.696.242 (2017). The metropolitan area of Makassar (Mamminasata) extends over 47 administrative districts (kecamatan), consisting of all 15 districts within the city, all nine districts of Takalar Regency, 11 (out of 18) districts of Gowa Regency and 12 (out of 14) districts of Maros Regency.

Districts of Takalar Regency which included in the metro area are, Mangara Bombang, Mappakasunggu, Sanrobone, Polombangkeng Selatan, Pattallassang, Polombangkeng Utara, Galesong Selatan, Galesong and Galesong Utara. Districts of Gowa Regency which included in the metro area are, Somba Opu, Bontomarannu, Pallangga, Bajeng, Bajeng Barat, Barombong, Manuju, Pattallassang, Parangloe, Bontonompo and Bontonompo Selatan. Districts of Maros Regency which included in the metro area are, Maros Baru, Turikale, Marusu, Mandai, Moncongloe, Bontoa, Lau, Tanralili, Tompo Bulu, Bantimurung, Simbang and Cenrana.

Climate

Makassar has a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am).

The average temperature for the year in Makassar is 27.5 °C or 81.5 °F, with little variation due to its near-equatorial latitude: the average high is around 32.5 °C or 90.5 °F and the average low around 22.5 °C or 72.5 °F all year long.

In contrast to the virtually consistent temperature, rainfall shows wide variation between months in Makassar due to movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone. Makassar averages around 3,137 millimetres or 123.50 inches of rain on 187 days during the year, but during the month with least rainfall – August – only 15 millimetres or 0.59 inches on two days of rain can be expected. In contrast, during its very wet wet season, Makassar can expect over 530 millimetres or 21 inches per month between December and February. During the wettest month of January, 734 millimetres or 28.90 inches can be expected to fall on twenty-seven rainy days.

| Climate data for Makassar | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.7 (87.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.4 (90.3) |

34.3 (93.7) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.6 (94.3) |

33.5 (92.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

32.6 (90.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.4 (72.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 734 (28.9) |

533 (21.0) |

391 (15.4) |

235 (9.3) |

127 (5.0) |

66 (2.6) |

48 (1.9) |

15 (0.6) |

83 (3.3) |

83 (3.3) |

273 (10.7) |

549 (21.6) |

3,137 (123.6) |

| Source: Weatherbase[31] | |||||||||||||

Main sights

Makassar is home to several prominent landmarks including:

- the 17th century Dutch fort Fort Rotterdam

- the Trans Studio Makassar—the third largest indoor theme park in the world

- the Karebosi Link—the first underground shopping centre in eastern Indonesia

- the floating mosque located at Losari Beach.

- the Bantimurung - Bulusaraung National Park well-known karst area, famous for the remarkable collection of butterflies in the local area, is nearby to Makassar (around 40 km to the north).

Demographics

Religion in Makassar (2010)[32]

Makassar is a multi-ethnic city, populated mostly by Makassarese and Buginese. The remainder are Torajans, Mandarese, Butonese, Chinese and Javanese. The current population is approximately 1.5 million, with a Metropolitan total of 2.2 million.

| Year | 1971 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2015 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | |||||||

The city is divided into fourteen districts (kecamatan), tabulated below with their 2010 Census population.[30]

| Name | Population Census 2010 |

|---|---|

| Mariso | 56,313 |

| Mamajang | 59,133 |

| Tamalate | 169,890 |

| Rappocini | 151,357 |

| Makassar | 81,901 |

| Ujung Padang | 27,206 |

| Wajo | 29,670 |

| Bontoala | 54,268 |

| Ujung Tanah | 46,771 |

| Tallo | 133,815 |

| Panukkukang | 141,524 |

| Manggala | 117,303 |

| Biring Kanaya | 167,843 |

| Tamalanrea | 101,669 |

Education

- State University of Makassar

- Hasanuddin University

- Alauddin Islamic State University

- Universitas Muhammadiyah Makassar

- Universitas Muslim Indonesia

By 2007, the city government began requiring all skirts of schoolgirls be below the knee.[33]

Traditional food

Makassar has several famous traditional foods. The most famous is Coto Makassar. It is a stew made from the mixture of nuts, spices, and selected offal which may include beef brain, tongue and intestine. Konro rib dish is also a popular traditional food in Makassar. Both Coto Makassar and Konro are usually consumed with Burasa or Ketupat, a glutinous rice cake. Another famous cuisine from Makassar is Ayam Goreng Sulawesi (Celebes fried chicken); the chicken is marinated with a traditional soy sauce recipe for up to 24 hours before being fried to a golden colour. The dish is usually served with chicken broth, rice and special sambal (chilli sauce).

In addition, Makassar is the home of Pisang Epe (pressed banana), as well as Pisang Ijo (green banana). Pisang Epe is a banana which is pressed, grilled, and covered with palm sugar sauce and sometimes consumed with Durian. Many street vendors sell Pisang Epe, especially around the area of Losari beach. Pisang Ijo is a banana covered with green coloured flours, coconut milk, and syrup. Pisang Ijo is sometimes served iced and often consumed during Ramadan.

References

- "Makassar Municipality in figures 2019 - BPS 2019".

- Ministry of Internal Affairs: Registration Book for Area Code and Data of 2013

- "Daftar 10 Kota Terbesar di Indonesia menurut Jumlah Populasi Penduduk". 16 September 2015.

- Andi Hajramurni: "Autonomy Watch: Makassar grows with waterfront city concept", The Jakarta Post, 13 June 2011

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2019.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2019..

- "26. Z. Irian Jaya". bappenas.go.id (Word DOC) (in Indonesian).

- Khosim, Amir (2007). Geografi (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Grasindo. p. 114. ISBN 9789797596194.

- "Perkembangan Properti Komersial" (PDF). Bank Sentral Republik Indonesia (in Indonesian). 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Riana, I Ketut (2009). Kakawin dēśa warṇnana, uthawi, Nāgara kṛtāgama: masa keemasan Majapahit. Indonesia: Penerbit Buku Kompas. p. 102. ISBN 978-9797094331.

49. Ikang saka sanusa nusa maksar butun banggawi kunir galiyau mwangi salaya sumba solot muar, muwah tikang-i wandhanambwanathawa maloko wwanin, ri serani timur makadiningangeka nusa tutur.

- Anthony Reid, Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia, Singapore 1999, pp.113-19; Poelinggomang, 2002, pp.22-23

- Andaya, Leonard. "Makasar's Moment of Glory." Indonesian Heritage: Early Modern History. Vol. 3, ed. Anthony Reid, Sian Jay and T. Durairajoo. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2001. 58–59.

- Maharani, Ina (8 November 2018). "Kenapa HUT Makassar Dirayakan Tiap 9 November? Ini Sejarahnya dan Penamaan Makassar" [Why is the Makassar Anniversary Celebrated Every November 9? This History and Naming Makassar]. Tribun Timur (in Indonesian). Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Reid 1999, pp.129-46

- Reid 1999, pp.146-54

- Carey, Peter. "Dipanagara and the Java War." Indonesian Heritage: Early Modern History. Vol. 3, ed. Anthony Reid, Sian Jay and T. Durairajoo. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2001. 112–13.

- "Sulawesi Selatan Arms". www.hubert-herald.nl.

- Carvalho, Rita Bernardes de. ""Bitter Enemies or Machiavellian Friends? Exploring the Dutch–Portuguese Relationship in Seventeenth-Century Siam"". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - A. Rodrigues, Baptista (13 July 2013). "Francisco Vieira de Figueiredo". Ourém. Notícias de Ourém (3884): Page 10.

- L, Klemen (1999–2000). "The capture of Makassar, February 1942". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- Kahin, George McTurnan (1952). Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Westerling (1952), p. 210

- MacKnight

- Sholl, Robert J. (26 July 1865). "Camden Harbour". The Inquirer & Commercial News. p. 3. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- "Pertumbuhan Ekonomi Makassar Membaik". Makassarterkini.com. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "Mamminasata Railway Realised in 2015". Indii.co.id. 19 May 2011. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "Makassar, neighbors to commence monorail construction next year". The Jakarta Post. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "Kalla Group Exits from Makassar Monorail Project | Yosefardi News". yosefardi.biz. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "Pelindo IV needs Rp 150b to expand Soekarno-Hatta seaport". 12 January 2012.

- Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

- "Weatherbase: Makassar Indonesia Records and Averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- "Population by Region and Religion: Makassar Municipality". BPS (in Indonesian). Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Warburton, Eve (January–March 2007). "No longer a choice" (89 ed.). Inside Indonesia. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

Further reading

- MacKnight, C.C., Voyage to Marege. Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia, Melbourne University Press, 1976.

- Reid, Anthony. 1999. Charting the shape of early modern Southeast Asia. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 9747551063. pp. 100–154.

- McCarthy, M., 2000, Indonesian divers in Australian waters. The Great Circle, vol. 20, No.2:120–137.

- Turner, S. 2003: Indonesia’s Small Entrepreneurs: Trading on the Margins. London, RoutledgeCurzon ISBN 070071569X 288pp. Hardback.

- Turner, S. 2007: Small-Scale Enterprise Livelihoods and Social Capital in Eastern Indonesia: Ethnic Embeddedness and Exclusion. Professional Geographer. 59 (4), 407–20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Makassar. |

- Indonesia Official Tourism Website

- Pinisi at Poatere Harbour, 2012. Photographs by Peter Loud