Kalba

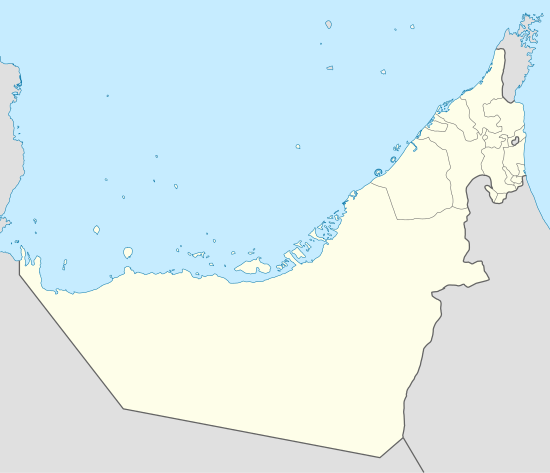

Kalba (Arabic: كَلْبَاء, romanized: Kalbāʾ) is a city in the Emirate of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). It is an exclave of Sharjah lying on the Gulf of Oman coast north of Oman. Khor Kalba (Kalba Creek), an important nature reserve and mangrove swamp, is located south of the town by the Omani border.

Kalba كَلْبَاء | |

|---|---|

| Kalba | |

Mangrove swamp in Khor Kalba | |

Flag | |

Kalba Location of Kalba | |

| Coordinates: 25°04′27″N 56°21′19″E | |

| Country | |

| Emirate | Sharjah |

| Government | |

| • Emir | Sultan bin Muhammad Al Qasimi |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 37,545[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (UAE standard time) |

Kalba Mangrove reserve is currently closed to the public and is being developed as an eco-tourism resort by the Sharjah Investment and Development Authority (Shurooq). A number of conservationists and ecologists have expressed concern regarding the project.[2]

History

Shell middens dating back to the fourth millennium BCE have been found at Kalba, as well as extensive remains of Umm Al Nar era settlement.[3]

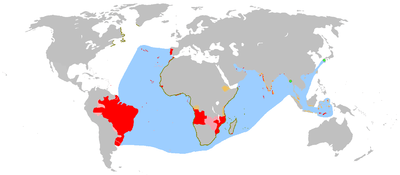

Portuguese

The town was captured by the Portuguese Empire in the 16th century and was referred to as Ghallah.[4]It was part of a series of fortified cities that the Portuguese had to control access to the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, like Khor Fakan, Muscat, Sohar, Seeb, Qurayyat and Muttrah.

It was attacked and sacked by the Sultan of Muscat's forces in March 1811 as part of the ongoing Omani campaign against the maritime forces of Al-Qasimi.[5] It was a Trucial State from 1936 to 1951, before being reincorporated into Sharjah.

Kalba was still being referred to as Ghallah at the time of J. G. Lorimer's 1906 survey of the Persian Gulf and Oman, when it consisted of some 300 areesh (date palm frond) houses, of Naqbiyin, Sharqiyin, Kunud and Abadilah tribes as well as a number of Baluchis and Persians.[6] It was home to ten boats trading with ports in the Persian Gulf and India.[7]

Majid bin Sultan bin Saqr Al Qasimi was granted the Shamaliyah region, including Kalba, as a fiefdom by his brother, Sheikh Salim bin Sultan Al Qasimi, Ruler of Sharjah. Kalba was subsequently ruled jointly by his two sons Hamad bin Majid and Ahmad bin Majid.

Hamad's son Said Bin Hamad Al Qasimi succeeded him in 1902, at the time when the ruler of neighbouring Fujairah, Hamad bin Abdallah Al Sharqi, managed to establish independence. Said bin Hamad lived in Ajman, leaving the administration of Kalba in the hands of a slave named Barut.[8]

Trucial state

By the 1920s, he took up residency in Kalba again and in 1936 was recognised by the British as a Trucial Ruler as an incentive to grant landing rights to an emergency air-strip as a backup to the Imperial Airways runway and fort at Al-Mahatta in the city of Sharjah.[9]

In April 1937, the deposed Ruler of Sharjah, Khalid bin Ahmad Al Qasimi, married Aisha, the daughter of Sheikh Said bin Hamad Al Qasimi. Said bin Hamad died suddenly at the end of April 1937 while visiting Khor Fakkan. Said bin Hamad's son, Hamad, was still a minor and so Aisha moved quickly to establish a regency, travelling to Kalba and organising the town's defences. For many years Said bin Hamad had lived in Ajman and entrusted a slave by the name of Barut to manage Kalba on his behalf, and Aisha now arranged for Barut to once again take charge as Wali. She sent a message to Khalid bin Ahmad, who was in Ras Al Khaimah at the time.[10]

A period of intense political infighting and negotiation between the many involved parties now followed. In June 1937, the notable residents of Kalba selected the slave Barut as Regent for the 12-year-old Hamad, but this solution was not accepted by the British and Khalid bin Ahmad was selected as regent. Increasingly seen as an influential and unifying figure by the Bedouin and the townspeople of the East Coast, he ruled over Dhaid and Kalba (delegating his rule in Kalba to Barut and choosing himself to live in Dhaid and Heera) until 1950, when he was too old and infirm to take a further role in affairs. He died that year[11] and the rule of Kalba reverted to the direct administration of Sharjah. Although there are British records of an insurgency in 1952 this appears to have been settled.[12][13]

That notwithstanding, there were almost constant outbreaks of squabbling and disputes between Kalba and neighbouring Fujairah (itself only recognised as a Trucial State by the British in 1952) which broke out into open fighting over a land dispute after the UAE was founded in 1971 and, in 1972 the newly founded Union Defence Force was called in to take control of the fighting which, by the time the UDF moved in, had killed 22 and seriously injured a dozen more. The dispute was finally settled after mediation between Sheikh Rashid of Dubai and other Rulers and a statement announcing the settlement sent out on 17 July 1972.[15]

City access

Khor Kalba is accessible by three roads.

The first merges after Wadi Al Helou (Arabic: وَادِي ٱلْحلًو) tunnel with Maliha Road (Arabic: شارع مليحة) which finally leads to the Sharjah-Kalba Road (90 km (56 mi)) from Sharjah International Airport.[16] There is also the Fujairah-Kalba Road (8 km (5.0 mi)).

The Khor Kalba Road extends until the border with Oman, and is one of the exit–entry points between the UAE and Oman.[17]

Rulers

- Majid bin Sultan Al Qasimi (1871–1900)

- Hamad bin Majid Al Qasimi (1900–1903)

- Said ibn Hamad Al Qasimi (1903–30 April 1937)

- Hamad bin Said Al Qasimi (30 April 1937 – 1951)

- Saqr bin Sultan Al Qasimi (1951–1952; Ruler of Sharjah from 1951–1965)

Britain recognized Kalba on 8 December 1936, and it was re-incorporated into Sharjah in 1952.

Gallery

The Shumayliyyah Mountains near Kalba

The Shumayliyyah Mountains near Kalba.jpg)

See also

References

- GD

- Todorova, Vesela (20 May 2012). "Mangrove fears over Emirates eco-tourism project". The National. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Heritage, Sharjah Directorate of Antiquities &. "Kalba – Sharjah Directorate of Antiquities & Heritage". sharjaharchaeology.com. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- Bey, Frauke (1982). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates. UK: Longman. p. 533. ISBN 0582277280.

- Qasimi, Sultan (1986). The Myth of Piracy in the Arabian Gulf. UK: Croom Helm. p. 153. ISBN 0709921063.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Vol II. British Government, Bombay. p. 576.

- Lorimer, JG (1908). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman & Central Arabia. Government of India. p. 1440.

- Heard-Bey, Frauke (2004). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates. Motivate. p. 91. ISBN 9781860631672.

- Heard-Bey, Frauke (2004). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates. Motivate. p. 296. ISBN 9781860631672.

- Heard-Bey, Frauke (2004). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates. Motivate. pp. 91–6. ISBN 9781860631672.

- Said., Zahlan, Rosemarie (2016). The Origins of the United Arab Emirates : a Political and Social History of the Trucial States. Taylor and Francis. p. 188. ISBN 9781317244653. OCLC 945874284.

- Secret Cabinet Office Record CC 52, April 1952, Cabinet Office minutes of Cabinet Meeting of 29 April 1952, pg. 72. The National Archive, UK.

- Heard-Bey, Frauke (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- "Livro das plantas de todas as fortalezas, cidades e povoaçoens do Estado da India Oriental / António Bocarro [1635]" (PDF).

- Wilson, Graeme (1999). Father of Dubai. UAE: Media Prima. p. 178. ISBN 9789948856450.

- Reporter, Shafaat Shahbandari, Staff (4 January 2017). "New road to link UAE, Oman by next year". GulfNews. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Gokulan, Dhanusha. "Confusion as checkpoint of Hatta-Oman closed". www.khaleejtimes.com. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kalba. |