Hirakata

Hirakata (枚方市, Hirakata-shi) is a city in northeastern Osaka Prefecture, Japan.[2] It is known for Hirakata Park, an amusement park which includes roller coasters made of wood.[3]

Hirakata 枚方市 | |

|---|---|

Hirakata Park | |

Flag  Emblem | |

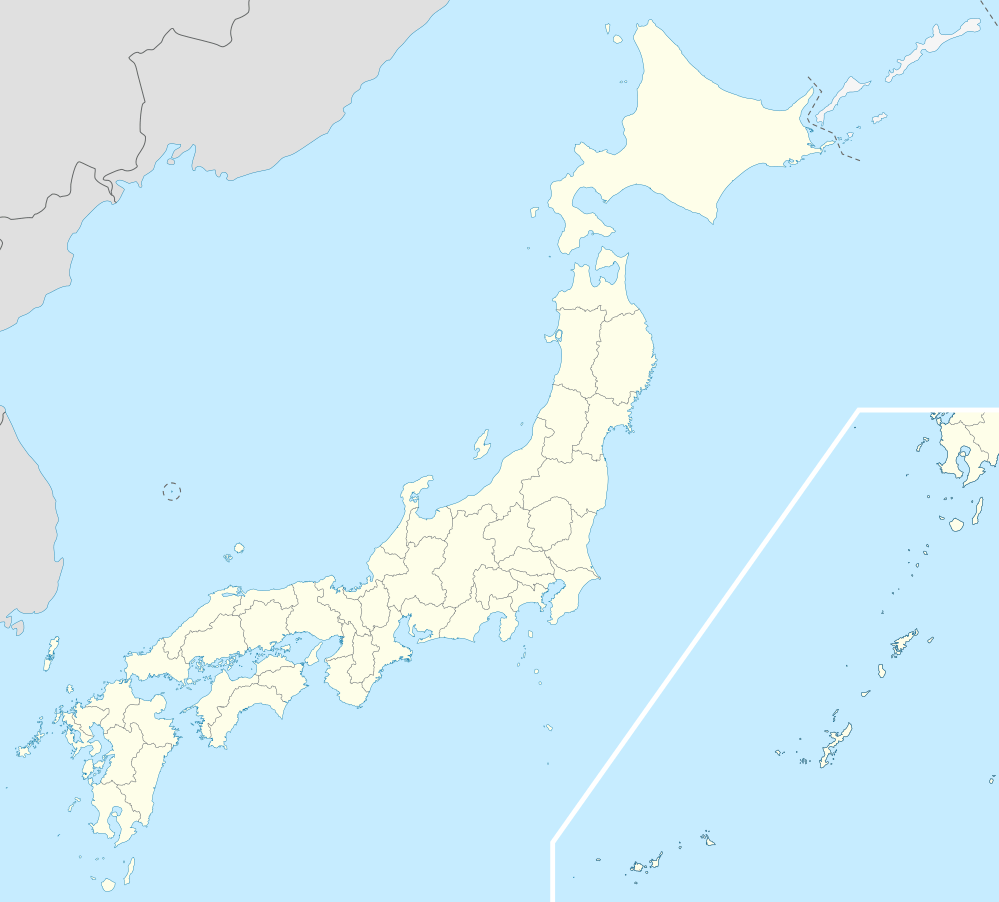

Location of Hirakata in Osaka Prefecture | |

Hirakata Location in Japan | |

| Coordinates: 34°49′N 135°39′E | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Kansai |

| Prefecture | Osaka Prefecture |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Takashi Fushimi[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 65.08 km2 (25.13 sq mi) |

| Population (October 31, 2019) | |

| • Total | 401,449 |

| • Density | 6,200/km2 (16,000/sq mi) |

| Symbols | |

| • Tree | Willow |

| • Flower | Chrysanthemum |

| • Bird | Common kingfisher |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (JST) |

| City hall address | 2-1-20 Ogaito-chō, Hirakata-shi, Osaka-fu 573-8666 |

| Website | Official website |

As of October 1, 2016, the city has an estimated population of 402,927, and a population density of 6,200 persons per km2. The total area of the city is 65.07 km2.

Eriko Aoki, author of "Korean children, textbooks, and educational practices in Japanese primary schools," stated that the city's location in proximity to both Osaka City and Kyoto contributed to its population growth of ten times its previous size from around 1973 to 2013.[4]

History

The modern city was founded on August 1, 1947. On April 1, 2001, Hirakata was designated as a special city of Japan.

Surrounding municipalities

- Osaka Prefecture

- Kyoto Prefecture

- Yawata

- Kyotanabe

- Nara Prefecture

Mayors

- Sōichirō Terashima (in office 1947 - 1955, 1959 - 1967) former mayor of Hirakata-chō

- Harufumi Hatakeyama (1955 - 1959)

- Tomizō Yamamura (1967 - 1975)

- Kazuo Kitamaki (1975 - 1991)

- Kazuo Ōshio (1991 - 1995)

- Hiroshi Nakatsuka (1995 - 2007)

- Osamu Takeuchi (2007 - 2015)

- Takashi Fushimi (2015–Present)

Demographics

Ethnic Koreans

As of 2013 the city has about 2,000 ethnic Koreans, including permanent residents of Japan, South Korean citizens, and those aligned to North Korea. Most Hirakata Koreans,[5] including children of school age, use Japanese names.[6] Most ethnic Korean children in Hirakata attend Japanese public schools, while some attend Chongryon schools located in Osaka City.[7] Many Koreans in Hirakata operate their own businesses. Hirakata has the "mother's society" or "Omoni no Kai", a voluntary association of ethnic Korean mothers. It also has branches of the Chongryon and Mindan, Japan's two major Korean associations. Hirakata has no particular Korean neighborhoods.[5]

There were about 3,000 ethnic Koreans in Hirakata in the pre-World War II period. In the 1930s Hirakata Koreans, fearful of keeping their own jobs, had negative attitudes towards Osaka-based Koreans who were looking for employment after having lost their jobs. Military construction was the most common job sector of that era's Korean population.[5]

Eriko Aoki stated that in 2013 there was still a sense of difference between the Koreans in Hirakata and the Koreans in Osaka.[5]

Education

Colleges and universities

- Kansai Gaidai University

- Osaka Dental University

- Kansai Medical University

- Setsunan University

- Osaka International University

- Osaka Institute of Technology

- National Tax College

Prefectural senior high schools

- Osaka Prefectural Hirakata High School (大阪府立枚方高等学校)

- Osaka Prefectural Nagao High School (大阪府立長尾高等学校)

- Osaka Prefectural Makino High School (大阪府立牧野高等学校)

- Korigaoka High School (大阪府立香里丘高等学校)

- Hirakatsuda High School (大阪府立枚方津田高等学校)

- Hirakata Nagisa High School (大阪府立枚方なぎさ高等学校)

Municipal high schools

- Osaka City Senior High School (大阪市立高等学校) - In Hirakata

Private senior high schools:

- Josho Keiko Gakuen Junior and Senior High School (常翔啓光学園高等学校)

- Tokai University Gyosei Junior and Senior High School (東海大学付属仰星高等学校)

- Toyo Gakuen Nagaodani High School (長尾谷高等学校)

Transportation

Rail

- Keihan Electric Railway

- Keihan Main Line Kozenji Station - Hirakata-koen Station - Hirakata-shi Station - Goten-yama Station - Makino Station - Kuzuha Station

- Katano Line Hirakata-shi Station - Miyanosaka Station - Hoshigaoka Station - Murano Station

- West Japan Railway Company

- Katamachi Line (Gakkentoshi Line) Tsuda Station - Fujisaka Station - Nagao Station

Highways

Companies with offices in Hirakata

- Komatsu Osaka plant

- Sanyo Electric Co R&D

Sister and friendship cities

.svg.png)

References

- https://www.city.hirakata.osaka.jp.e.cu.hp.transer.com/0000004030.html

- "Hirakata" at Britannica.com; retrieved 2013-8-28.

- "Hirakta Park" at Osaka-info.jp Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved 2013-8-28.

- Aoki, Eriko. "Korean children, textbooks, and educational practices in Japanese primary schools" (Chapter 8). In: Ryang, Sonia. Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin (Routledge Studies in Asia's Transformations). Routledge, October 8, 2013. ISBN 1136353054, 9781136353055. Start: p. 157. CITED: p. 169-170.

- Aoki, Eriko. "Korean children, textbooks, and educational practices in Japanese primary schools" (Chapter 8). In: Ryang, Sonia. Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin (Routledge Studies in Asia's Transformations). Routledge, October 8, 2013. ISBN 1136353054, 9781136353055. Start: p. 157. CITED: p. 170.

- Aoki, Eriko. "Korean children, textbooks, and educational practices in Japanese primary schools" (Chapter 8). In: Ryang, Sonia. Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin (Routledge Studies in Asia's Transformations). Routledge, October 8, 2013. ISBN 1136353054, 9781136353055. Start: p. 171.

- Aoki, Eriko. "Korean children, textbooks, and educational practices in Japanese primary schools" (Chapter 8). In: Ryang, Sonia. Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin (Routledge Studies in Asia's Transformations). Routledge, October 8, 2013. ISBN 1136353054, 9781136353055. Start: p. 157. CITED: p. 170-171.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hirakata, Osaka. |

- Hirakata City official website (in Japanese)

- www.city.hirakata.osaka.jp.e.cu.hp.transer.com (in English)