Tsukuba, Ibaraki

Tsukuba (つくば市, Tsukuba-shi) is a city located in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. As of 1 June 2019, the city had an estimated population of 239,747, and a population density of 845 persons per km². Its total area is 283.72 square kilometres (109.54 square miles). It is known as the location of the Tsukuba Science City (筑波研究学園都市, Tsukuba Kenkyū Gakuen Toshi), a planned science park developed in the 1960s.

Tsukuba つくば市 | |

|---|---|

View of Mount Tsukuba and Tsukuba Center | |

Flag  Seal | |

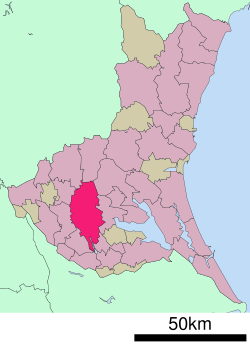

Location of Tsukuba in Ibaraki Prefecture | |

Tsukuba | |

| Coordinates: 36°5′0.5″N 140°4′35.2″E | |

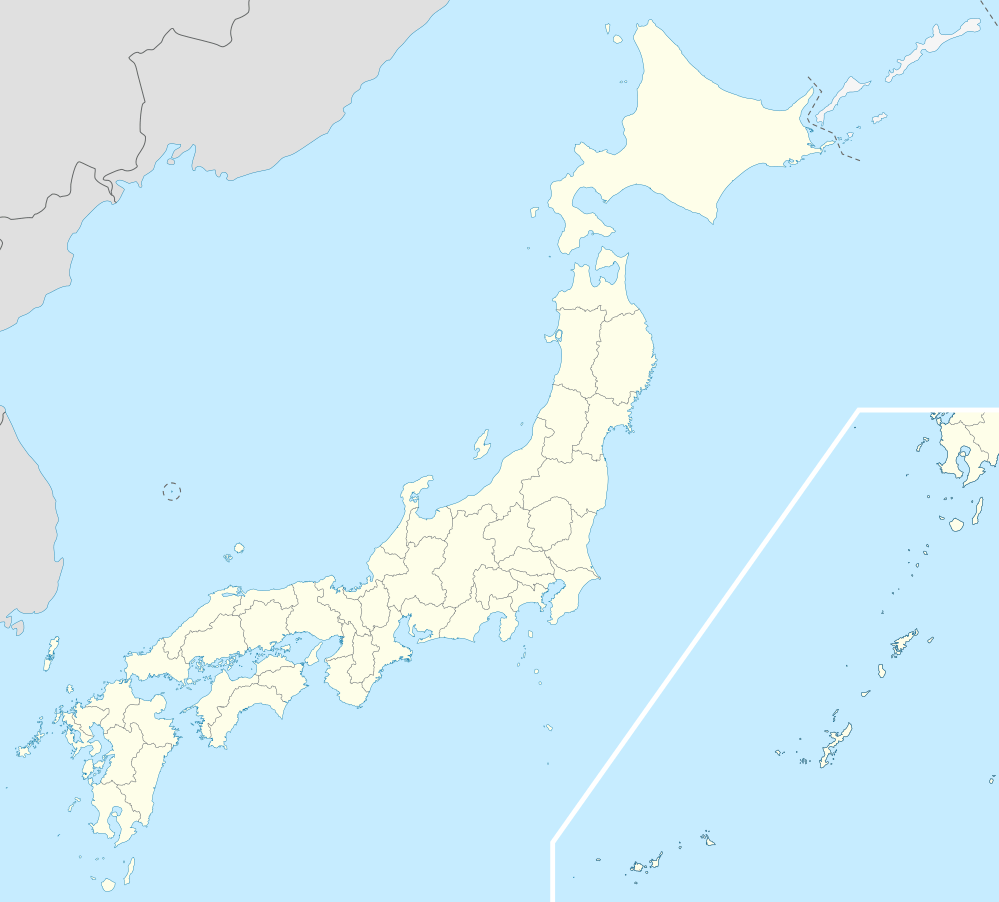

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Kantō |

| Prefecture | Ibaraki Prefecture |

| Area | |

| • Special city | 283.72 km2 (109.54 sq mi) |

| Population (June 1, 2019) | |

| • Special city | 239,747 |

| • Density | 850/km2 (2,200/sq mi) |

| • Metro [1] (2015) | 843,402 (19th) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| - Tree | Japanese zelkova |

| - Flower | Hoshizaki-yukinoshita (Saxifraga stolonifera Curtis f. aptera (Makino) H.Hara) |

| - Bird | Ural owl |

| Address | 2530-2 Karima, Tsukuba-shi, Ibaraki-ken 305-8555 |

| Website | www.city.tsukuba.lg.jp |

Geography

Located in southern Ibaraki Prefecture, Tsukuba is located to the south of Mount Tsukuba, from which it takes its name.

Surrounding municipalities

- Ibaraki Prefecture

- Tsukubamirai

- Jōsō

- Shimotsuma

- Chikusei

- Sakuragawa

- Ishioka

- Tsuchiura

- Ushiku

- Ryūgasaki

History

Mount Tsukuba has been a place of pilgrimage since at least the Heian period. During the Edo period, parts of what later became the city of Tsukuba were administered by a junior branch of the Hosokawa clan at Yatabe Domain, one of the feudal domains of the Tokugawa shogunate. With the creation of the municipalities system after the Meiji Restoration on April 1, 1889, the town Yatabe was established within Tsukuba District, Ibaraki.

Beginning in the 1960s, the area was designated for development. Construction of the city centre, the University of Tsukuba and 46 public basic scientific research laboratories began in the 1970s. Tsukuba Science City became operational in the 1980s. The Expo '85 world's fair was held in the area of Tsukuba Science City, which at the time was still divided administratively between several small towns and villages. Attractions at the event included the 85-metre (279 ft) Technocosmos, which at that time was the world's tallest Ferris wheel.[2]

On November 30, 1987 the town of Yatabe merged with the neighboring towns of Ōho and Toyosato and the village of Sakura to create the city of Tsukuba. The neighboring town of Tsukuba merged with the city of Tsukuba on January 1, 1988, followed by the town of Kukizaki on November 1, 2002.

By 2000, the city's 60 national research institutes and two national universities had been grouped into five zones: higher education and training, construction research, physical science and engineering research, biological and agricultural research, and common (public) facilities. These zones were surrounded by more than 240 private research facilities. Among the most prominent institutions are the University of Tsukuba (1973; formerly Tokyo University of Education); the High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK); the Electrotechnical Laboratory; the Mechanical Engineering Laboratory; and the National Institute of Materials and Chemical Research. The city has an international flair, with about 7,500 foreign students and researchers from as many as 133 countries living in Tsukuba at any one time.

Over the past several decades, nearly half of Japan's public research and development budget has been spent in Tsukuba. Important scientific breakthroughs by its researchers include the identification and specification of the molecular structure of superconducting materials, the development of organic optical films that alter their electrical conductivity in response to changing light, and the creation of extreme low-pressure vacuum chambers. Tsukuba has become one of the world's key sites for government-industry collaborations in basic research. Earthquake safety, environmental degradation, studies of roadways, fermentation science, microbiology, and plant genetics are some of the broad research topics having close public-private partnerships.

On April 1, 2007 Tsukuba was designated a Special city with increased autonomy.

Following the Fukushima I nuclear accidents in 2011, evacuees from the accident zone reported that municipal officials in Tsukuba refused to allow them access to shelters in the city unless they presented certificates from the Fukushima government declaring that the evacuees were "radiation free".[3]

On May 6, 2012, Tsukuba was struck by a tornado that caused heavy damage to numerous structures and left approximately 20,000 residents without electricity. The storm killed one 14-year-old boy and injured 45 people. The tornado was rated an F-3 by the Japan Meteorological Agency, making it the most powerful tornado to ever hit Japan. Some spots had F-4 damage.[4]

Economy

Companies headquartered in Tsukuba

- Intel Japan (1980-2016)

- Cyberdyne Inc.

- SoftEther Corporation

- TonQ Corporation

Manufacturing

- Komori Corporation has its main manufacturing plant in Tsukuba.[5]

Education

Higher education

- University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba Campus

- National University Corporation Tsukuba University of Technology

- Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Tsukuba Campus

- Tsukuba Gakuin University

Primary and secondary education

Tsukuba has 37 elementary schools, 15 middle schools, two combined middle school/high schools and six high schools, along with one special education school. In addition, it has an international school, Tsukuba International School, and a Brazilian school, the Instituto Educare (former Escola Pingo de Gente).[6]

Transportation

Railway

Highway

- Jōban Expressway – Yatabe IC, Tsukuba JCT, Yatabe-Higashi PA, Sakura-Tsuchiura IC

- Ken-Ō Expressway – Tsukuba-Chuo IC, Tsukuba JCT, Tsukuba-Ushiku IC

- Japan National Route 6

- Japan National Route 125

- Japan National Route 354

- Japan National Route 408

- Japan National Route 468

Media

- Tsukuba Community Broadcast Inc. – Radio Tsukuba

- Academic Newtown Community Cable Service (ACCS)

Local attractions

Tsukuba Science City

Tsukuba Science City is a center for research and education in the city of Tsukuba, located northeast of Tokyo. The idea of constructing the science city was by the late Ichiro Kono, former minister of construction, and Kuniomi Umezawa, former vice minister of the science and technology agency.[7] Another key figure for the development of the Science City is Leo Esaki.[8] What sets Tsukuba apart from other town developments in Japan is the large scale and fast pace of its development into a place with high quality of scientific innovation.[8]

History

In September 1963, the national government of Japan, led by Ichiro Kono and Kniomi Umezawa, ordered the development of a science city in the area around the mountain Tsukuba.[7] Reasons behind this decision included the overcrowding in Tokyo, the overflow of applicants to Japanese elite universities, a desire of conservative politicians to decrease the influence of liberal teachers and students, and a need to catch up with the West in terms of scientific knowledge.[8] Furthermore, it was already clear that there was a demand for new research facilities and a fresh approach to university education. This fresh approach was prevalent in the United States; therefore, Japan's Ministry of Education decided to transfer a part of the Tokyo University of Education to the Tsukuba area. The campus of the university was modeled after the University of California, San Diego, campus.[8] After a new university structure was introduced; the power of teachers decreased and the power of administrative management increased. Furthermore, the new structure led to better research facilities, a separate independent research department and the implementation of a board for general policies and regulations.[7]

In 1966, after a few years of intensive study, the government started the project by buying land in the Tsukuba area.[7] The acquiring of land to build on was done by negotiation over prices between the government and landowners. The parcels of land with the most suitable price were purchased. This is reason for the odd shape of the government-owned land in Tsukuba; it is 18 kilometers long from north to east and 6 kilometers wide from east to west.[7] Due to this shape walking is not common in the city.[8]

The building of facilities started in June 1969. The initial building plan was ten years, but in 1980 it became clear that that would not be the case. However, in March 1980 all the facilities that were meant to be built were up and running to a certain extent.[7]

Between 1970 and 1980 researchers and their families started to move to Tsukuba. This move was a culture shock for the families from Tokyo due to the dirt roads and open fields in Tsukuba.[8]

Initially, Tsukuba was built for travel by car due to having no train station. It was actually Japan's first city that promoted automobile travel over public transport.[8] In 2005, a train station was built in the city.[9] The Tsukuba Express travels from Tokyo to the Science City in 45 minutes.[10]

Tsukuba Expo 1985

In order to promote the positive aspects of science and technology, an International Science and Technology Exposition was held. This was a landmark for the science city. The reasons behind the expo were to establish a positive national image of Tsukuba Science City and to gain international recognition that Tsukuba was a place of science. The Expo attracted around 20 million Japanese and foreign visitors.[8]

Leo Esaki

Leo Esaki became the president of the University of Tsukuba in 1992.[11] His presidency marked a new era of reform for the Tsukuba Science City. Leo Esaki is a Nobel prize winner and worked at IBM prior to becoming president of the University of Tsukuba. Unlike other Japanese university presidents he had no academic background and no former ties with the University of Tsukuba. This was part of the reason why he was chosen as president. Due to his history in the corporate world, he was able to create a climate were companies and graduate students could work together closely.[11] When the university was founded a good relationship between the students of the university and the nearby companies was expected. However, over the years this ambition disappeared into the background.[11] In these years there was a severe lack in interaction between the facilities of the University and the private companies in the area. This meant that there was no joint research happening.[12] In July 1994, Esaki introduced Tsukuba Advanced Research Alliance (TARA). This is a partnership between the university, foreign researchers, Tsukuba's national research labs, and corporate laboratories based in the city.[8]

Criticism

From the start there has been a lot of criticism on Tsukuba Science City. The first criticism on the city was that it was not habitable. Wives of the first researchers were used to putting garbage on the side of the road in order for it to get picked up. However, this was not the case in the mid-1970s. Until that time only farmers had lived there and they would process their own garbage into mulch. Because the garbage did not get picked up, it started smelling in the streets. This enraged the housewives and they demanded a garbage service. In order to meet the demand, a pit was dug where the waste could be dumped until a garbage service would be developed in the city. It is important to note that in the nineties Tsukuba had the most innovative garbage system of Japan.[8]

Another criticism levied by national government critics is that Tsukuba Science City is a waste of taxpayer's money. They also believe that Tsukuba is an example of government control of academic and research organization. In addition, social critics feel that Tsukuba's social organization is unfavorable as it lacks traditional Japanese culture.[8]

In Garner[13] the city is described as being ‘flat’ due to a lack of city life. Even though Tsukuba Science City has an impressive number of research and development facilities as well as a large number of companies it still is not able to reach the same level of innovation as science cities that do have stimulating city life. However, this might be changing because in 2006 Tsukuba Science City started focusing on creating more city life.[13]

Museums

See also Tsukuba Science Bus Tours

Other attractions

- Mount Tsukuba

- Hirasawa Kangai archaeological site (National Historic Site)

- Site of Oda Castle (National Historic Site)

- Kanamura Wake Ikazuchi Shrine

Sister city relations

Noted people from Tsukuba

- Leo Esaki, Nobel Prize winner[19]

- Susumu Hirasawa, progressive-electronic musician has a studio in Tsukuba[20]

- Mitsuhiro Ishida, mixed martial artist

- Yasuaki Kurata, actor

- Hideki Shirakawa, Nobel Prize winner[21]

- Haruka Sunada, volleyball player

- Minanogawa Tōzō, sumo wrestler

- Hiroki Yamada, baseball player

References

- "UEA Code Tables". Center for Spatial Information Science, University of Tokyo. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- James W. Dearing (1995). Growing a Japanese Science City: Communication in Scientific Research. London: Routledge.

- Jiji Press, "Tsukuba asked evacuees for radiation papers", Japan Times, 20 April 2011, p. 2.

- "Tornado in Tsukuba rated as strongest ever : National : DAILY YOMIURI ONLINE (The Daily Yomiuri)". Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- "About Our Plant". Komori Corporation. 2019.

- "Escolas Brasileiras Homologadas no Japão" (Archive). Embassy of Brazil in Tokyo. Retrieved on October 13, 2015.

- Bloom, Justin L.; Asano, Shinsuke (1981). "Tsukuba Science City: Japan Tries Planned Innovation". Science. 212 (4500): 1239–1247. doi:10.1126/science.212.4500.1239. JSTOR 1685782. PMID 17738819.

- W., Dearing, James (1995). Growing a Japanese science city : communication in scientific research. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780203210581. OCLC 647375233.

- Terada, Hirokazu (2013). データブック日本の私鉄 [Databook: Japan's Private Railways].. Japan: Neko Publishing. ISBN 9784777013364. OCLC 840099891.

- "Tsukuba Express | JapanVisitor Japan Travel Guide". www.japanvisitor.com. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- Normile, Dennis (1994). "Leo Esaki: An Outsider Brings a Culture Change to Tsukuba". Science. 266 (5190): 1473–1474. doi:10.1126/science.266.5190.1473. JSTOR 2885161. PMID 17841701.

- EDGINGTON, DAVID W. (1989). "New strategies for technology development in Japanese cities and regions". The Town Planning Review. 60 (1): 1–27. doi:10.3828/tpr.60.1.2348803u1n3m4324. JSTOR 27798156.

- Garner, Cathy (2006). "Viewpoint: Science Cities: refreshing the concept for 21 st-century places". The Town Planning Review. 77 (5): i–vi. JSTOR 41229022.

- "A Message from the Peace Commission: Information on Cambridge's Sister Cities," February 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- Richard Thompson. "Looking to strengthen family ties with 'sister cities'," Boston Globe, October 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- 友好城市 [Friendly cities]. Foreign Affairs Office of Shenzhen. 2008-03-22.

- 国际友好城市一览表 [International Friendship Cities List]. Foreign Affairs Office of Shenzhen. 2011-01-20.

- 友好交流 [Friendly exchanges]. Foreign Affairs Office of Shenzhen. 2011-09-13.

- "University of Tsukuba Prospectus Leo Esaki". Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- 「補償金もDRMも必要ない」――音楽家 平沢進氏の提言 (1/4) (in Japanese). ITmedia. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

- "University of Tsukuba Prospectus Hideki Shirakawa". Retrieved 2013-02-28.

External links

- Official website (in Japanese)