Helmand Province

Helmand (/ˈhɛlmənd/ HEL-mənd;[2] Pashto/Dari: هلمند), also known as Hillmand or Helman and, in ancient times, as Hermand and Hethumand,[3] is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, in the south of the country. It is the largest province by area, covering 58,584 square kilometres (20,000 sq mi) area. The province contains 13 districts, encompassing over 1,000 villages, and roughly 1,442,500 settled people.[1] Lashkargah serves as the provincial capital.

Helmand هلمند | |

|---|---|

Arghandab River Valley between Kandahar and Lashkargah | |

Map of Afghanistan with Helmand highlighted | |

| Coordinates (Capital): 31.0°N 64.0°E | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Lashkargah |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Mohammad Yasin Khan |

| Area | |

| • Total | 58,584 km2 (22,619 sq mi) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,442,500 |

| • Density | 25/km2 (64/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+4:30 (Afghanistan Time) |

| ISO 3166 code | AF-HEL |

| Main languages | Pashto & Balochi |

Helmand was part of the Greater Kandahar region until made into a separate province by the Afghan government in the 20th century. The province has a domestic airport (Bost Airport), in the city of Lashkargah and heavily used by NATO-led forces. The former British Camp Bastion and U.S. Camp Leatherneck is a short distance southwest of Lashkargah.

The Helmand River flows through the mainly desert region of the province, providing water used for irrigation. The Kajaki Dam, which is one of Afghanistan's major reservoirs, is located in the Kajaki district. Helmand is believed to be one of the world's largest opium-producing regions, responsible for around 42% of the world's total production.[4][5] This is believed to be more than the whole of Burma, which is the second largest producing nation after Afghanistan. The region also produces tobacco, sugar beets, cotton, sesame, wheat, mung beans, maize, nuts, sunflowers, onions, potato, tomato, cauliflower, peanut, apricot, grape, and melon.[6]

Since the 2001 War in Afghanistan, Helmand Province has been a hotbed of insurgent activities.[7][8][9] It has been considered to be Afghanistan's "most dangerous" province.[10][11]

History

Helmand culture

Helmand culture of western Afghanistan was a Bronze Age culture of the 3rd millennium BC. It is exemplified by such major sites as Shahr-i Sokhta, Mundigak, and Bampur.

The term "Helmand civilization" was proposed by M. Tosi. This civilization flourished between 2500 BC and 1900 BC, and may have coincided with the great flourishing of the Indus Valley Civilisation. This was also the final phase of Periods III and IV of Shahr-i Sokhta, and the last part of Mundigak Period IV.

According to Jarrige et al.,

... the pottery of Mundigak I, the earliest occupation of the complex, corresponds to the Mehrgarh III pottery, in technique — quality of the paste and manufacture — as well as in the shapes and decoration, probably within a phase dated to the end of the 5th millennium [BC]."[12]

There were also links between Shahr-i Sokhta I, II and III periods, and Mundigak III and IV periods, and between the sites of Balochistan and the Indus valley at the end of the 4th millennium, as well as in the first half of the 3rd millennium BC.

The Jiroft culture is closely related to the Helmand culture. The Jiroft culture flourished in the eastern Iran, and the Helmand culture in western Afghanistan at the same time. In fact, they may represent the same cultural area. The Mehrgarh culture, on the other hand, is far earlier.

Achaemenid times

Helmand was inhabited by ancient peoples and governed by the Medes before falling to the Achaemenids.

Later, the area was part of the ancient Arachosia polity, and a frequent target for conquest because of its strategic location in Asia, which connects Southern, Central and Southwest Asia.

The Helmand river valley is mentioned by name in the Avesta (Fargard 1:13) as Haetumant, one of the early centers or origins of the Zoroastrian faith, in pre-Islamic Afghan history. However, owing to the presence of non-Zoroastrians even though Zoroastrians being dominant before the Islamization of Afghanistan – particularly Hindus and Buddhists – the Helmand and Kabul regions were also known as "White India" in those days.[13]

Some Vedic scholars (e.g. Kochhar 1999) also believe the Helmand valley corresponds to the Sarasvati area mentioned in the Rig Veda as the homeland for the Indo-Aryan migrations into the Indian Subcontinent, ca. 1500 BCE.[14]

Alexander the Great to modern times

It was invaded in 330 BC by Alexander the Great and became part of the Seleucid Empire. Later, it came under the rule of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, who erected a pillar there with a bilingual inscription in Greek and Aramaic. The territory was referred to as part of Zabulistan and ruled by the sun-worshipping Hindus Zunbils before the Muslim Arabs arrived in the 7th century, who were led by Abdur Rahman bin Samara. It later fell to the Saffarids of Zaranj and saw the first Muslim rule. Mahmud of Ghazni made it part of the Ghaznavids in the 10th century, who were replaced by the Ghurids.

After the destructions caused by Genghis Khan and his Mongol army in the 13th century, the Timurids established rule and began rebuilding Afghan cities. From about 1383 until his death in 1407, it was governed by Pir Muhammad, a grandson of Timur. By the early 16th century, it fell to Babur. However, the area was often contested by the Shia Safavids and Sunni Mughals until the rise of Mir Wais Hotak in 1709. He defeated the Safavids and established the Hotaki dynasty. The Hotakis ruled it until 1738 when the Afsharids defeated Shah Hussain Hotaki at what is now Old Kandahar.

In 1747, it finally submitted to Ahmad Shah Durrani and since then remained part of the modern state of Afghanistan. Some fighting took place during the 19th century Anglo-Afghan wars between the British and the local Afghans. In 1880, the British assisted the forces of Abdur Rahman Khan in re-establishing Afghan rule over the warring tribes. The area stayed calm for 100 years until the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Helmand was the center of the USAID program in the 1960s to develop the Helmand and Arghandab Valley Authority (HAVA) – it became known locally as "little America". The program laid out tree-lined streets in Lashkargah, built a network of irrigation canals and constructed a large hydroelectric dam. The development program was abandoned when pro-Soviet Union forces seized power in 1978, although much of the province is still irrigated by the HAVA.

Karzai and Ghani era

During Operation Enduring Freedom, the United States Agency for International Development program contributed to a counter-narcotics initiative called the Alternative Livelihoods Program (ALP) in the province. It paid communities to work to improve their environment and economic infrastructure as an alternative to opium poppy farming. The project undertook drainage and canal rehabilitation projects. In 2005 and 2006, there were problems in getting promised finance to communities and this was a source of considerable tension between the farmers and the Coalition forces.

After it was decided to deploy British troops to the Province, PJHQ tasked 22 SAS to conduct a reconnaissance of the province. The review was led by Mark Carleton-Smith, who found the province largely at peace due to the brutal rule of Sher Mohammad Akhundzada, and a booming opium-fuelled economy that benefited the pro-government warlords. In June he reported back to the MoD warning them not to remove Akhundzada and against the deployment of a large British force which would likely cause conflict where none existed.[15]

It was announced in January 2006 in the British Parliament that International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) would replace the U.S. troops in the province as part of Operation Herrick. The British 16 Air Assault Brigade would be the core of the force in Helmand Province. British bases were located in the districts of Sangin, Lashkargah and Grishk. British forces were replaced in Sangin by elements of the United States Marine Corps I Marine Expeditionary Force Forward.

In summer 2006, Helmand was one of the provinces involved in Operation Mountain Thrust, a combined NATO-Afghan mission targeted at Taliban fighters in the south of the country. In July 2006, this offensive mission essentially stalled in Helmand as NATO, primarily British, and Afghan troops were forced to take increasingly defensive positions under heavy insurgent pressure. In response, British troop levels in the province were increased, and new encampments were established in Sangin and Grishk. Fighting was particularly heavy in the districts of Sangin, Naway, Nawzad and Garmsir. There were reports that the Taliban saw Helmand province as a key testing area for their ability to take and hold Afghan territory from NATO-led Afghan National Security Forces.[16] Commanders on the ground described the situation as the most brutal conflict the British Army had been involved in since the Korean War.

In Autumn 2006, British troops started to reach "cessation of hostilities" agreements with local Taliban forces around the district centers where they had been stationed earlier in the summer.[17] Under the terms of the agreement, both sets of forces were to withdraw from the conflict zone. This agreement from the British forces implied that the strategy of holding key bases in the district, as requested by Afghan President Hamid Karzai, was essentially untenable with the levels of British troop deployment. The agreement was also a setback for Taliban fighters, who were desperate to consolidate their gains in the province, but were under heavy pressure from various NATO offensives.

News reports identified the insurgents involved in the fighting as a mix of Taliban fighters and warring tribal groups who are heavily involved in the province's lucrative opium trade.[18] Given the amount of drugs produced in the area, it is likely that foreign drug traffickers were also involved.

Fighting continued throughout the winter, with British and allied troops taking a more pro-active stance against the Taliban insurgents. Several operations were launched including Operation Silicone at the start of spring. In May 2007, Mullah Dadullah, one of the Taliban's top commanders, along with 11 of his men were killed by NATO-led Afghan forces in Helmand.

In April 2008, about 1,500 2nd Battalion 7th Marines occupied over 300 square miles (800 km2) of Helmand River valley and neighboring Farah Province. The operation was to set up forward operation bases and train the Afghan National Police in an area with little or no outside support.

Also in 2008, an Embedded Training Team from the Oregon Army National Guard led a Kandak of Afghan National Army troops in fighting against the Taliban in Lashkargah, as seen in the documentary Shepherds of Helmand.

In June 2009, Operation Panther's Claw was launched with the stated aim of securing control of various canal and river crossings and establishing a lasting ISAF presence in an area described by Lt. Col. Richardson as "one of the main Taliban strongholds" ahead of the 2009 Afghan presidential election.

In July 2009, around 4,000 U.S. Marines pushed into the Helmand River valley in a major offensive to liberate the area from Taliban insurgents. The operation, dubbed Operation Khanjar (Operation Dagger), was the first major push since U.S. President Obama's request for 21,000 additional soldiers in Afghanistan, targeting the Taliban insurgents.

In February 2013, BBC reported that corruption occurs in Afghan National Police bases, with some bases arming children, using them as servants and sometimes sexually abusing them;[19] in early March 2013, the New York Times reported that government corruption is rampant with routine accusations against the police of shaking down and sexually abusing civilians causing loyalty to the government to be weaker.[20]

Politics and governance

The current Governor of the province is Mohammad Yasin Khan. The city of Lashkargah is the capital of Helmand province. All law enforcement activities throughout the province are controlled by the Afghan National Police (ANP). Helmand's border with neighboring Balochistan province of Pakistan is monitored and protected by the Afghan Border Police (ABP), which is part of the ANP. The border is called the Durand Line and is known to be one of the most dangerous in the world due to heavy militant activities and illegal smugglings.[21] A provincial Police Chief is assigned to lead both the ANP. The Police Chief represents the Ministry of the Interior in Kabul. The ANP is backed by other Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), including the NATO-led forces.

Transport and economy

Bost Airport serves the population of Helmand for domestic flights to other parts of the country. It is designed for civilian use. NATO-led forces are heavily using the airport at Camp Bastion, where Camp Leatherneck is located nearby.

There is no rail service. Primary roads include the ring road passes through Helmand from Kandahar to Delaram. There is a major north-south route (Highway 611) that goes from Lashkargah to Sangin. About 33% of Helmands roads are not passable during certain seasons and in some areas, there are no roads at all.

Farming is the main source of income for the majority. This includes agriculture and animal husbandry. Animals include cows, sheep, goats, and chicken. Donkeys and camels are used for labor. The province has a potential for fishery. The region produce the following: opium, tobacco, cotton, wheat and potato.

Healthcare

The percentage of households with clean drinking water fell from 28% in 2005 to 3% in 2011.[22] The percentage of births attended to by a skilled birth attendant increased from 2% in 2005 to 3% in 2011.[22]

Education

The overall literacy rate (6+ years of age) increased from 5% in 2005 to 12% in 2011.[22] The overall net enrollment rate (6–13 years of age) fell from 6% in 2005 to 4% in 2011.[22]

Demographics

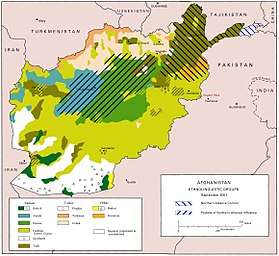

The population of Helmand Province was reported at 1,442,500 in the year 2018.[1] It is mostly a tribal and rural society, with the native ethnic Pashtuns being predominant; there is a significant Baloch minority in the south, and there are small minorities of Tajiks, Hazaras and others. There may also be small number of Hindus and Sikhs who run businesses in the provincial capital, Lashkargah.[23] The Pashtuns are divided into the following tribes: Barakzai (32%), Nurzai (16%), Alakozai (9%), and Eshaqzai (5.2%).[6] All the inhabitants practice Sunni Islam except the small number of Hazaras who are Shi'as and the Sikhs who follow Sikhism.

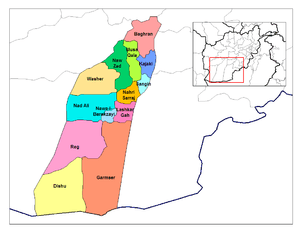

Districts

| District | Capital | Population[3] | Area | Number of villages and ethnic groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baghran | 129,947 | 3,124 km2 | 38 villages. Pashtun.[24] | |

| Dishu | 29,005 | 9,485 km2 | 80% Pashtun and 20% Baloch[25][26] | |

| Garmsir | 107,153 | 10,345 km2 | 112 villages. Pashtun.[27] | |

| Kajaki | 119,023 | 1,976 km2 | 220 villages[28] 100% Pashtun[29] | |

| Khanashin | 17,333 | 13,153 km2 | Pashtun[30] | |

| Lashkargah | Lashkargah | 201,546 | 998 km2 | 160 villages. Pashtun.[31] |

| Marjah | Marjah | 2,300 km2 | 95% Pashtun, 5% Tajik and Hazara.[32] | |

| Musa Qala | Musa Qala | 138,896 | 1,694 km2 | Pashtun[33] |

| Nad Ali | 235,590 | 4,564 km2 | 90% Pashtun, 10% Turkmen and

Hazara.[34] | |

| Grishk (Nahri Saraj) | 166,827 | 1,543 km2 | 97 villages. Pashtun[35] | |

| Nawa-I-Barakzayi | 300,000 | 4135 km2 | 350 villages. Pashtun[36] | |

| Nawzad | 108,258 | 4,135 km2 | 100% Pashtun[37][38] | |

| Sangin | Sangin | 66,901 | 508 km2 | 99% Pashtun, 1% Hazara, Tajik and Arab.[39] |

| Washir | 31,476 | 4,319 km2 | Pashtun[40] | |

| Bahram Chah | (300-3500) |

Politicians

- Abdul Jabar Qahraman

- Merwali Khan Barakzai

- Mohammad Daoud

See also

- Provinces of Afghanistan

- 2007 Helmand province airstrikes

- Dashti Margo

- Operation Khanjar

Gallery

- Images of Helmand Province

The Kajaki Dam (left) and spillway (right)

The Kajaki Dam (left) and spillway (right) Mountains in Musa Qala District during sunset

Mountains in Musa Qala District during sunset Camp Bastion at night

Camp Bastion at night New Afghan recruit

New Afghan recruit Forward Operating Base Edinburgh

Forward Operating Base Edinburgh Soldier of the Afghan National Army (ANA) with an RPG-7 at Camp Shorabak in Helmand province

Soldier of the Afghan National Army (ANA) with an RPG-7 at Camp Shorabak in Helmand province%2C_Afghan_National_Police_and_Afghan_Border_Police_officers_stand_in_formation_during_an_ALP_graduation_ceremony_at_the_regional_ALP_training_center_in_the_Lashkar_Gah_district%2C_Helmand_130606-A-RI362-222.jpg) Afghan National Security Forces, which includes Afghan National Police (ANP), Afghan Border Police (ABP) and Afghan Local Police (ALP)

Afghan National Security Forces, which includes Afghan National Police (ANP), Afghan Border Police (ABP) and Afghan Local Police (ALP) Afghans with national flags

Afghans with national flags

References

- "Settled Population of Helmand province by Civil Division, Urban, Rural and Sex-2012-13" (PDF). Islamic Republic of Afghanistan: Central Statistics Organization. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- "Helmand". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- "Hillmand Province". Government of Afghanistan and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

-

Pat McGeough (2007-03-05). "Where the poppy is king". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05.

More than 90 per cent of the province's arable land is choked with the hardy plant. A 600-strong, US-trained eradication force is hopelessly behind schedule on its target for this growing season in Helmand - to clear about a third of the crop, which is estimated to be a head-spinning 70,000 hectares.

-

"Afghanistan still the largest producer of opium: UN report". Zee News. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

She said opium cultivation is concentrated in the south of the country, with just one province ‘Helmand’ accounting for 42% of all the illicit production in the world. Many of the provinces with the highest levels of production also have the worst security problems.

- "Helmand" (PDF). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies. May 1, 2010. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

- MacKenzie, Jean. "Could Helmand be the Dubai of Afghanistan?".

- "UK's Helmand mission was 'flawed'". Bbc.co.uk. June 12, 2010.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Afghanistan: Clashes in Helmand leave civilians dead, displaced". Refworld.org.

- Anderson, Ben (June 22, 2015). "Notes from Afghanistan's Most Dangerous Province".

- Rowlatt, Justin (April 7, 2016). "Afghan forces face 'decisive' battle". Bbc.co.uk.

- Jarrige, J.-F., Didier, A. & Quivron, G. (2011) Shahr-i Sokhta and the Chronology of the Indo-Iranian Borderlands. Paléorient 37 (2) : 7-34 academia.edu

- "AVESTA: VENDIDAD (English): Fargard 1". avesta.org.

- Kochhar, Rajesh, 'On the identity and chronology of the Ṛgvedic river Sarasvatī' in Archaeology and Language III; Artefacts, languages and texts, Routledge (1999), ISBN 0-415-10054-2.

- Farrell, Theo, Unwinnable: Britain’s War in Afghanistan, 2001–2014, Bodley Head, 2017 ISBN 1847923461, 978-1847923462, P.233

- "Coalition 'retakes Taleban towns'". BBC News. 2006-07-19. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- Smith, Michael (2006-10-01). "British troops in secret truce with the Taliban". The Times. London. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- Leithead, Alastair (2006-07-14). "Unravelling the Helmand impasse". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- Ben Anderson (25 February 2013). "Afghan police: Panorama uncovers corruption in Helmand bases". BBC News. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- James Dao (3 March 2013). "As Marines Exit Afghan Province, a Feeling That a Campaign Was Worth It". New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- Ascher, W.; Heffron, J. (2010-12-12). Cultural Change and Persistence: New Perspectives on Development. Springer. ISBN 9780230117334.

- Archive, Civil Military Fusion Centre, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-31. Retrieved 2014-05-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Welcome - Naval Postgraduate School" (PDF). Nps.edu. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "Loading..." (PDF). 345069709.cs-utilities.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Mrrd-nabdp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Mrrd-nabdp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2013.

- Kajaki District Archived 2013-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- "Loading..." (PDF). Mrrd-nabdp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Mrrd-nabdp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

- "Loading..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Helmand Province. |