Sarasvati River

The Sarasvati River (IAST: sárasvatī nadī́) was one of the Rigvedic rivers mentioned in the Rig Veda and later Vedic and post-Vedic texts. The Sarasvati River played an important role in the Vedic religion, appearing in all but the fourth book of the Rigveda.

The goddess Sarasvati was originally a personification of this river, but later developed an independent identity.[2] The Sarasvati is also considered by Hindus to exist in a metaphysical form, in which it formed a confluence with the sacred rivers Ganges and Yamuna, at the Triveni Sangam.[3] According to Michael Witzel, superimposed on the Vedic Sarasvati river is the heavenly river Milky Way, which is seen as "a road to immortality and heavenly after-life."[4]

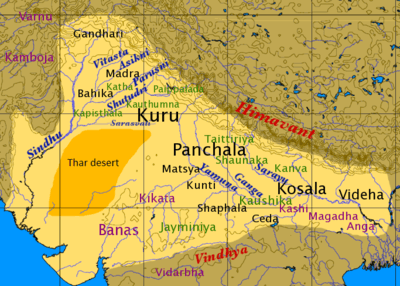

Rigvedic and later Vedic texts have been used to propose identification with present-day rivers, or ancient riverbeds. The Nadistuti hymn in the Rigveda (10.75) mentions the Sarasvati between the Yamuna in the east and the Sutlej in the west. Later Vedic texts like the Tandya and Jaiminiya Brahmanas, as well as the Mahabharata, mention that the Sarasvati dried up in a desert.

Since the late 19th-century, scholars have identified the Vedic Saraswati river as the Ghaggar-Hakra River system, which flows through northwestern India and eastern Pakistan, between the Yamuna and the Sutlej. Satellite images have pointed to the more significant river once following the course of the present day Ghaggar River.[5] Scholars have observed that major Indus Valley Civilization sites at Kalibangan (Rajasthan), Banawali and Rakhigarhi (Haryana), Dholavira and Lothal (Gujarat) also lay along this course.[6][7]

However, identification of the Vedic Sarasvati with the Ghaggar-Hakra system is problematic, since the Sarasvati is not only mentioned separately in the Rig Veda, but is described as having dried up by the time of the composition of the later Vedas and Hindu epics.[8] In the words of Annette Wilke, the Sarasvati had been reduced to a "small, sorry trickle in the desert", by the time that the Vedic people migrated into north-west India.[9] [10][lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2][11]

Recent geophysical research suggests that the Ghaggar-Hakra system was a system of monsoon-fed rivers and that the Indus Valley Civilisation may have declined as a result of climatic change, when the monsoons that fed the rivers diminished at around the time civilisation diminished some 4,000 years ago.[12][lower-alpha 3][13][14][15] Yet, another study suggests that between 9,000 and 4,500 years ago the Ghaggar was perennial, "receiving sediments from the Higher and Lesser Himalayas," which "likely facilitated development of the early Harappan settlements along its banks.".[16]

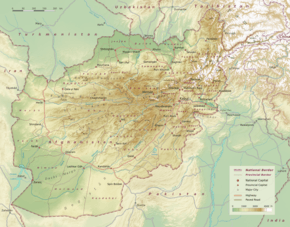

"Sarasvati" may also be identified with the Helmand or Haraxvati river in southern Afghanistan,[17] the name of which may have been reused in its Sanskrit form as the name of the Ghaggar-Hakra river, after the Vedic tribes moved to the Punjab.[17][18][lower-alpha 4] Sarasvati of the Rig Veda may also refer to two distinct rivers, with the family books referring to the Helmand River, and the more recent 10th mandala referring to the Ghaggar-Hakra.

The identification with the Ghaggar-Hakra system took on new significance in the early 21st century,[19] with some suggesting an earlier dating of the Rig Veda; renaming the Indus Valley Civilisation as the "Sarasvati culture", the "Sarasvati Civilization", the "Indus-Sarasvati Civilization" or the "Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization,"[20][21][22] suggesting that the Indus Valley and Vedic cultures can be equated;[23] and rejecting the Indo-Aryan migrations theory, which postulates a migration at 1500 BCE.[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6] This alleged equation is incompatible with linguistic and archeological evidence, which shows striking differences between the two cultures.[24]

Etymology

Sarasvatī is the feminine nominative singular form of the adjective sarasvat (which occurs in the Rigveda[25] as the name of the keeper of the celestial waters), derived from ‘sarasa’ + ‘vat’, meaning ‘having’. Saras appears, in turn, to be the compound of ‘sa’, a prefix meaning ‘with’, plus ‘rasa’, sap or juice, or water, and is defined in the first instance as ‘anything flowing or fluid’ according to Monier-Williams dictionary. Mayrhofer considers unlikely a connection with the root *sar- ‘run, flow’.[26]

Sarasvatī may be a cognate of Avestan Haraxvatī, perhaps[27] originally referring to Arədvī Sūrā Anāhitā (modern Ardwisur Anahid), the Zoroastrian mythological world river, which would point to a common Indo-Iranian myth of a cosmic or mystical Sáras-vat-ī river. In the younger Avesta, Haraxvatī is Arachosia, a region described to be rich in rivers, and its Old Persian cognate Harauvati, which gave its name to the present-day Hārūt River in Afghanistan, may have referred to the entire Helmand drainage basin (the center of Arachosia).

Importance in Hinduism

The Saraswati river was revered and considered important for Hindus because it is said that it was on this river's banks, along with its tributary Drishadwati, in the Vedic state of Brahmavarta, that Vedic Sanskrit had its genesis,[28] and important Vedic scriptures like initial part of Rigveda and several Upanishads were supposed to have been composed by Vedic seers. In the Manusmriti, Brahmavarta is portrayed as the "pure" centre of Vedic culture. Bridget and Raymond Allchin in The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan took the view that "The earliest Aryan homeland in India-Pakistan (Aryavarta or Brahmavarta) was in the Punjab and in the valleys of the Sarasvati and Drishadvati rivers in the time of the Rigveda."[29]

Rigveda

The Sarasvati River is mentioned in all but the fourth book of the Rigveda. The most important hymns related to Sarasvati are RV 6.61, RV 7.95 and RV 7.96.[30] Macdonell and Keith provided a comprehensive survey of Vedic references to the Sarasvati River in their Vedic Index.[31]

Praise

- The Sarasvati is praised lavishly in the Rigveda as the best of all the rivers. In RV 2.41.16,

- अम्बितमे नदीतमे देवितमे सरस्वति । अप्रशस्ताइव स्मसि प्रशस्तिमम्ब नस्कृधि ॥

- ambitame nadītame devitame sarasvati । apraśastāiva smasi praśastimamba naskṛdhi ॥

- "Oh Mother Saraswati you are the greatest of mothers, greatest of rivers, greatest of goddesses. Even though we are not worthy, please grant us distinction".

- Other verses of praise include RV 6.61.8-13, RV 7.96 and RV 10.17. In some hymns, the Indus river seems to be more important than the Sarasavati, especially in the Nadistuti sukta. In RV 8.26.18, the white flowing Sindhu 'with golden wheels' is the most conveying or attractive of the rivers.

- RV 7.95.2. and other verses (e.g. RV 8.21.18) speak of the Sarasvati pouring "milk and ghee." Rivers are often likened to cows in the Rigveda, for example in RV 3.33.1,

- Rigveda,4.58.1 says

- "May purifying Sarasvati with all the plenitude of her forms of plenty, rich in substance by the thought, desire our sacrifice."

- "She, the impeller to happy truths, the awakener in consciousness to right mentalisings, Sarasvati, upholds the sacrifice."

- "Sarasvati by the perception awakens in consciousness the great flood (the vast movement of the ritam) and illumines entirely all the thoughts"[32]

As a goddess

The Sarasvati is mentioned some fifty times in the hymns of the Rig Veda. It is mentioned in thirteen hymns of the late books (1 and 10) of the Rigveda.[33] Only two of these references are unambiguously to the river: 10.64.9, calling for the aid of three "great rivers", Sindhu, Sarasvati and Sarayu; and 10.75.5, the geographical list of the Nadistuti sukta. The others invoke Sarasvati as a goddess without direct connection to a specific river.

In 10.30.12, her origin as a river goddess may explain her invocation as a protective deity in a hymn to the celestial waters. In 10.135.5, as Indra drinks Soma he is described as refreshed by Sarasvati. The invocations in 10.17 address Sarasvati as a goddess of the forefathers as well as of the present generation. In 1.13, 1.89, 10.85, 10.66 and 10.141, she is listed with other gods and goddesses, not with rivers. In 10.65, she is invoked together with "holy thoughts" (dhī) and "munificence" (puraṃdhi), consistent with her role as a goddess of both knowledge and fertility.

Though Sarasvati initially emerged as a river goddess in the Vedic scriptures, in later Hinduism of the Puranas, she was rarely associated with the river. Instead she emerged as an independent goddess of knowledge, learning, wisdom, music and the arts. The evolution of the river goddess into the goddess of knowledge started with later Brahmanas, which identified her as Vāgdevī, the goddess of speech, perhaps due to the centrality of speech in the Vedic cult and the development of the cult on the banks of the river. It is also possible to postulate two originally independent goddesses that were fused into one in later Vedic times.[2] Aurobindo has proposed, on the other hand, that "the symbolism of the Veda betrays itself to the greatest clearness in the figure of the goddess Sarasvati ... She is, plainly and clearly, the goddess of the World, the goddess of a divine inspiration ...".[34]

Other Vedic texts

In post-Rigvedic literature, the disappearance of the Sarasvati is mentioned. Also the origin of the Sarasvati is identified as Plaksa Prasravana (Peepal tree or Ashwattha tree as known in India and Nepal).[35][36]

In a supplementary chapter of the Vajasaneyi-Samhita of the Yajurveda (34.11), Sarasvati is mentioned in a context apparently meaning the Sindhu: "Five rivers flowing on their way speed onward to Sarasvati, but then become Sarasvati a fivefold river in the land."[37] According to the medieval commentator Uvata, the five tributaries of the Sarasvati were the Punjab rivers Drishadvati, Satudri (Sutlej), Chandrabhaga (Chenab), Vipasa (Beas) and the Iravati (Ravi).

The first reference to the disappearance of the lower course of the Sarasvati is from the Brahmanas, texts that are composed in Vedic Sanskrit, but dating to a later date than the Veda Samhitas. The Jaiminiya Brahmana (2.297) speaks of the 'diving under (upamajjana) of the Sarasvati', and the Tandya Brahmana (or Pancavimsa Br.) calls this the 'disappearance' (vinasana). The same text (25.10.11-16) records that the Sarasvati is 'so to say meandering' (kubjimati) as it could not sustain heaven which it had propped up.[38][lower-alpha 7]

The Plaksa Prasravana (place of appearance/source of the river) may refer to a spring in the Siwalik mountains. The distance between the source and the Vinasana (place of disappearance of the river) is said to be 44 Ashwin (between several hundred and 1,600 miles) (Tandya Br. 25.10.16; cf. Av. 6.131.3; Pancavimsa Br.).[39]

In the Latyayana Srautasutra (10.15-19) the Sarasvati seems to be a perennial river up to the Vinasana, which is west of its confluence with the Drshadvati (Chautang). The Drshadvati is described as a seasonal stream (10.17), meaning it was not from Himalayas. Bhargava[40] has identified Drashadwati river as present day Sahibi river originating from Jaipur hills in Rajasthan. The Asvalayana Srautasutra and Sankhayana Srautasutra contain verses that are similar to the Latyayana Srautasutra.

Post-Vedic texts

Mahabharata

According to the Mahabharata, the Sarasvati dried up to a desert (at a place named Vinasana or Adarsana)[41][42] and joins the sea "impetuously".[43] MB.3.81.115 locates the state of Kurupradesh or Kuru Kingdom to the south of the Sarasvati and north of the Drishadvati. The dried-up, seasonal Ghaggar River in Rajasthan and Haryana reflects the same geographical view described in the Mahabharata.

According to Hindu scriptures, a journey was made during the Mahabharata by Balrama along the banks of the Saraswati from Dwarka to Mathura. There were ancient kingdoms too (the era of the Mahajanapads) that lay in parts of north Rajasthan and that were named on the Saraswati River.[44][45][46][47]

Puranas

Several Puranas describe the Sarasvati River, and also record that the river separated into a number of lakes (saras).[48]

In the Skanda Purana, the Sarasvati originates from the water pot of Brahma and flows from Plaksa on the Himalayas. It then turns west at Kedara and also flows underground. Five distributaries of the Sarasvati are mentioned.[49] The text regards Sarasvati as a form of Brahma's consort Brahmi.[50] According to the Vamana Purana 32.1-4, the Sarasvati rose from the Plaksa tree (Pipal tree).[48]

The Padma Purana proclaims:

One who bathes and drinks there where the Gangā, Yamunā and Sarasvati join enjoys liberation. Of this there is no doubt."[51]

Smritis

- In the Manu Smriti, the sage Manu, escaping from a flood, founded the Vedic culture between the Sarasvati and Drishadvati rivers. The Sarasvati River was thus the western boundary of Brahmavarta: "the land between the Sarasvati and Drishadvati is created by God; this land is Brahmavarta."[52]

- Similarly, the Vasistha Dharma Sutra I.8-9 and 12-13 locates Aryavarta to the east of the disappearance of the Sarasvati in the desert, to the west of Kalakavana, to the north of the mountains of Pariyatra and Vindhya and to the south of the Himalaya. Patanjali's Mahābhāṣya defines Aryavarta like the Vasistha Dharma Sutra.

- The Baudhayana Dharmasutra gives similar definitions, declaring that Aryavarta is the land that lies west of Kalakavana, east of Adarsana (where the Sarasvati disappears in the desert), south of the Himalayas and north of the Vindhyas.

Contemporary mythological meaning

Diana Eck notes that the power and significance of the Sarasvati for present-day India is in the persistent symbolic presence at the confluence of rivers all over India.[53] Although "materially missing",[54] she is the third river, which emerges to join in the meeting of rivers, thereby making the waters thrice holy.[54]

After the Vedic Sarasvati dried, new myths about the rivers arose. Sarasvati is described to flow in the underworld and rise to the surface at some places.[9] For centuries, the Sarasvati river existed in a "subtle or mythic" form, since it corresponds with none of the major rivers of present-day South Asia.[3] The confluence (sangam) or joining together of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers at Triveni Sangam, Allahabad, is believed to also converge with the unseen Sarasvati river, which is believed to flow underground. This despite Allahabad being a considerable distance from the possible historic routes of an actual Sarasvati river.

At the Kumbh Mela, a mass bathing festival is held at Triveni Sangam, literally "confluence of the three rivers", every 12 years.[3][55][56] The belief of Sarasvati joining at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna originates from the Puranic scriptures and denotes the "powerful legacy" the Vedic river left after her disappearance. The belief is interpreted as "symbolic".[57] The three rivers Sarasvati, Yamuna, Ganga are considered consorts of the Hindu Trinity (Trimurti) Brahma, Vishnu (as Krishna) and Shiva respectively.[50]

In lesser known configuration, Sarasvati is said to form the Triveni confluence with rivers Hiranya and Kapila at Somnath. There are several other Trivenis in India where two physical rivers are joined by the "unseen" Sarasvati, which adds to the sanctity of the confluence.[58]

According to Michael Witzel, superimposed on the Vedic Sarasvati river is the heavenly river Milky Way, which is seen as "a road to immortality and heavenly after-life."[4][59][60] The description of the Sarasvati as the river of heavens, is interpreted to suggest its mythical nature.[61]

Romila Thapar notes that "once the river had been mythologized through invoking the memory of the earlier river, its name - Sarasvati - could be applied to many rivers, which is what happened in various parts of the [Indian] subcontinent."[18]

Several present-day rivers are also named Sarasvati, after the Vedic Sarasvati:

- Sarsuti is the present-day name of a river originating in a submontane region (Ambala district) and joining the Ghaggar near Shatrana in PEPSU. Near Sadulgarh (Hanumangarh) the Naiwala channel, a dried out channel of the Sutlej, joins the Ghaggar. Near Suratgarh the Ghaggar is then joined by the dried up Drishadvati river.

- Sarasvati is the name of a river originating in the Aravalli mountain range in Rajasthan, passing through Sidhpur and Patan before submerging in the Rann of Kutch.

- Saraswati River, a tributary of Alaknanda River, originates near Badrinath

- Saraswati River in Bengal, formerly a distributary of the Hooghly River, has dried up since the 17th century.

Identification theories

Already since the 19th century, attempts have been made to identify the mythical Sarasvati of the Vedas with physical rivers.[62] Many think that the Vedic Sarasvati river once flowed east of the Indus (Sindhu) river.[57] Scientists, geologists as well as scholars have identified the Sarasvati with many present-day or now defunct rivers.

Two theories are popular in the attempts to identify the Sarasvati. Several scholars have identified the river with the present-day Ghaggar-Hakra River or dried up part of it, which is located in Northwestern India and Pakistan.[63][61][20][21] A second popular theory associates the river with the Helmand river or an ancient river in the present Helmand Valley in Afghanistan.[17][64]

Others consider Sarasvati a mythical river, an allegory not a "thing".[65]

The identification with the Ghaggar-Hakra system took on new significance in the early 21st century,[19] suggesting an earlier dating of the Rig Veda, and renaming the Indus Valley Civilisation as the "Sarasvati culture", the "Sarasvati Civilization", the "Indus-Sarasvati Civilization" or the "Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization,"[20][21][22] suggesting that the Indus Valley and Vedic cultures can be equated.[23]

Rig Vedic course

The Rig Veda contains several hymns which give an indication of the flow of the geography of the river, and an identification with the Ghaggra-Hakra:

- RV 3.23.4 mentions the Sarasvati River together with the Drsadvati River and the Āpayā River.

- RV 6.52.6 describes the Sarasvati as swollen (pinvamānā) by the rivers (sindhubhih).

- RV 7.36.6, "sárasvatī saptáthī síndhumātā" can be translated as "Sarasvati the Seventh, Mother of Floods,"[66] but also as "whose mother is the Sindhu", which would indicate that the Sarasvati is here a tributary of the Indus.[lower-alpha 8]

- RV 7.95.1-2, describes the Sarasvati as flowing to the samudra, a word now usually translated as "ocean."[lower-alpha 9]

- RV 10.75.5, the late Rigvedic Nadistuti sukta, enumerates all important rivers from the Ganges in the east up to the Indus in the west in a clear geographical order. The sequence "Ganges, Yamuna, Sarasvati, Shutudri" places the Sarasvati between the Yamuna and the Sutlej, which is consistent with the Ghaggar identification.

Yet, the Rig Veda also contains clues for an identification with the Helmand river in Afghanistan:

- The Sarasvati River is perceived to be a great river with perennial water, which does not apply to the Hakra and Ghaggar.[67]

- The Rig Veda seems to contain descriptions of several Sarasvati's. The earliest Sararvati is said to be similar to the Helmand in Afghanistan which is called the Harakhwati in the Āvestā.[67]

- Verses in RV 6.61 indicate that the Sarasvati river originated in the hills or mountains (giri), where she "burst with her strong waves the ridges of the hills (giri)". It is a matter of interpretation whether this refers only to the Himalayan foothills, where the present-day Sarasvati (Sarsuti) river flows, or to higher mountains.

The Rig Veda was composed during the latter part of the late Harappan period, and according to Shaffer, the reason for the predominance of the Sarasvati in the Rigveda is the late Harappan (1900-1300 BCE) population shift eastwards to Haryana.[68]

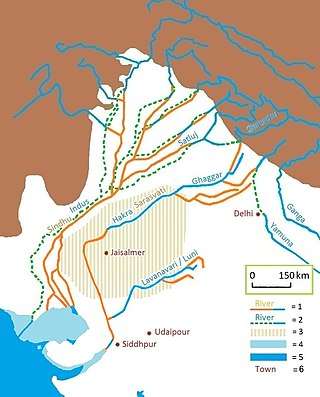

Ghaggar-Hakra River

1 = ancient river

2 = today's river

3 = today's Thar desert

4 = ancient shore

5 = today's shore

6 = today's town

The present Ghaggar-Hakra River is a seasonal river in India and Pakistan that flows only during the monsoon season, but satellite images in possession of the ISRO and ONGC have confirmed that the major course of a river ran through the present-day Ghaggar River.[69] Late in the 2nd millennium BCE the Ghaggar-Hakra fluvial system dried up, which affected the Harappan civilisation. Painted Grey Ware sites (ca. 1000 BCE) have been found in the bed and not on the banks of the Ghaggar-Hakra river, suggesting that the river had dried up before this period.[70][71]

Identification with the Sarasvati

A number of archaeologists and geologists have identified the Sarasvati river with the present-day Ghaggar-Hakra River, or the dried up part of it.[61][20][21][72][73][74][75][76][77] According to R.U.S. Prasad, "we [...] find a considerable body of opinions [sic] among the scholars, archaeologists and geologists, who hold that the Sarasvati originated in the Shivalik hills [...] and descended through Adi Badri, situated in the foothills of the Shivaliks, to the plains [...] and finally debouched herself into the Arabian sea at the Rann of Kutch."[78]

In the 19th and early 20th century a number of scholars, archaeologists and geologists have identified the Vedic Sarasvati River with the Ghaggar-Hakra River, such as Christian Lassen (1800-1876),[79] Max Müller (1823-1900),[80] Marc Aurel Stein (1862-1943),[70] C.F. Oldham[81] and Jane Macintosh.[82] Similarly, recent archaeologists and geologists, such as Philip and Virdi (2006), K.S. Valdiya (2013) have identified the Sarasvati with Ghaggar.[83] Danino notes that "the 1500 km-long bed of the Sarasvati" was "rediscovered" in the 19th century.[84] According to Danino, "most Indologists" were convinced in the 19th century that "the bed of the Ghaggar-Hakra was the relic of the Sarasvati."[84]

Archaeologists Gregory Possehl and Jane McIntosh refer to the Ghaggar-Hakra river as "Sarasvati" throughout their respective 2002 and 2008 books on the Indus Civilisation,[85][86] and Gregory Possehl stated:

"Linguistic, archaeological, and historical data show that the Sarasvati of the Vedas is the modern Ghaggar or Hakra."[86]

According to Valdiya, "it is plausible to conclude that once upon a time the Ghagghar was known as "Sarsutī"," which is "a corruption of "Sarasvati"," because "at Sirsā on the bank of the Ghagghar stands a fortress called "Sarsutī". Now in derelict condition, this fortress of antiquity celebrates and honours the river Sarsutī."[87]

Chatterjee et al. (2019) identify the Sarasvati with the Ghaggar, arguing that during "9-4.5 ka the river was perennial and was receiving sediments from the Higher and Lesser Himalayas," which "likely facilitated development of the early Harappan settlements along its banks.".[16]

Tectonics

Some paleo-environmental scientists have proposed that the Hakkra was fed by Himalayan sources, which made it a mighty river,[lower-alpha 10] but dried-up between 2500 BCE and 1900 BCE, due to tectonic disturbances which caused a tilt in topography of Northwest India, resulting in the migration of rivers. According to this theory, the Sutlej moved westward and became a tributary of the Indus River,[lower-alpha 11] while the Yamuna moved eastward and became a tributary of the Ganges, supposedly in the early 2nd millennium BCE, while reaching its current bed by 1st millennium BCE.[lower-alpha 12] The Drishadvati bed retained only a small seasonal flow. The water loss due to these movements caused the Ghaggar-Hakra river to dry up in the Thar Desert.[97][98][lower-alpha 13][lower-alpha 14]

Objections

Romila Thapar terms the identification controversial and dismisses it, noticing that the descriptions of Sarasvati flowing through the high mountains does not tally with Ghaggar's course and suggests that Sarasvati is Haraxvati of Afghanistan.[18] Wilke suggests that the identification is problematic since the Ghaggar-Hakra river was already dried up at the time of the composition of the Vedas,[8] let alone the migration of the Vedic people into northern India.[10][11]

Giosan et al., in their study Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilisation,[62] make clear that the Ghaggar-Hakra fluvial system was not a large glacier-fed Himalayan river, but a monsoonal-fed river.[lower-alpha 15][lower-alpha 16] They concluded that the Indus Valley Civilisation died out because the monsoons, which fed the rivers that supported the civilisation, diminished. With the rivers drying out as a result, the civilisation diminished some 4000 years ago.[62] This in particular effected the Ghaggar-Hakra system, which became ephemeral and was largely abandoned.[102] The Indus Valley Civilisation had the option to migrate east toward the more humid regions of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, where the decentralised late Harappan phase took place.[102]

Clift et al. (2012), using dating of zircon sand grains, have shown that subsurface river channels near the Indus Valley Civilisation sites in Cholistan immediately below the presumed Ghaggar-Hakra channel show sediment affinity not with the Ghagger-Hakra, but instead with the Beas River in the western sites and the Sutlej and the Yamuna in the eastern ones, further weakening the hypothesis that the Ghaggar-Hakra was once a large river, but suggesting that the Yamuna itself, or a channel of the Yamuna, along with a channel of the Sutlej may have flowed west some time between 47,000 BCE and 10,000 BCE. The drainage from the Yamuna may have been lost from the Ghaggar-Hakra well before the beginnings of Indus civilisation.[14]

Ajit Singh et al. (2017) show that the paleochannel of the Ghaggar-Hakra is a former course of the Sutlej, which diverted to its present course between 15,000 and 8,000 years ago, well before the development of the Harappan Civilisation. Ajit Singh et al. conclude that the urban populations settled not along a perennial river, but a monsoon-fed seasonal river that was not subject to devastating floods.[15][103]

Rajesh Kocchar further notes that, even if the Sutlej and the Yamuna had drained into the Ghaggar during Rig Vedic, it still would not fit the Rig Vedic descriptions because "the snow-fed Satluj and Yamuna would strengthen lower Ghaggar. Upper Ghaggar would still be as puny as it is today."[104]

Helmand river

An alternative suggestion for the identity of the early Rigvedic Sarasvati River is the Helmand River and its tributary Arghandab[1] in the Arachosia region in Afghanistan, separated from the watershed of the Indus by the Sanglakh Range. The Helmand historically besides Avestan Haetumant bore the name Haraxvaiti, which is the Avestan form cognate to Sanskrit Sarasvati. The Avesta extols the Helmand in similar terms to those used in the Rigveda with respect to the Sarasvati: "the bountiful, glorious Haetumant swelling its white waves rolling down its copious flood".[105] However unlike the Rigvedic Sarasvati, Helmand river never attained the status of a deity despite the praises in the Avesta.[106]

The identification of the Sarasvati river with the Helmand river was first proposed by E. Thomas in 1886, followed by Alfred Hillebrandt a couple of years thereafter. However, in the same year, Geologist R.D. Oldham, refuted this Afghan Sarasvatī thesis. [1] Indologist A.B. Keith (1879-1944) also didn't subscribe to this theory and stated that there is no conclusive evidence to identify the Sarasvati with the Helmand river.[107]

According to Konrad Klaus, the geographic situation of the Sarasvati and the Helmand rivers are similar. Both flow into a terminal lakes: the Helmand into a swamp in the Iranian plateau (the extended wetland and lake system of Hamun-i-Helmand). This matches the Rigvedic description of the Sarasvati flowing to the samudra, which according to him at that time meant 'confluence', 'lake', 'heavenly lake, ocean'; the current meaning of 'terrestrial ocean' was not even felt in the Pali Canon.[108]

Rajesh Kocchar, after a detailed analysis of the Vedic texts and geological environments of the rivers, concludes that there are two Sarasvati rivers mentioned in the Rigveda. The early Rigvedic Sarasvati, which he calls Naditama Sarasvati, is described in suktas 2.41, 7.36 etc. of the family books of the Rigveda, and drains into a samudra. The description of the Naditama Sarasvati in the Rigveda matches the physical features of the Helmand River in Afghanistan, more precisely its tributary the Harut River, whose older name was Haraxvatī in Avestan. The later Rigvedic Sarasvati, which he calls Vinasana Sarasvati, is described in the Rigvedic Nadistuti sukta (10.75), which was composed centuries later, after an eastward migration of the bearers of the Rigvedic culture to the western Gangetic plain some 600 km to the east. The Sarasvati by this time had become a mythical "disappeared" river, and the name was transferred to the Ghaggar which disappeared in the desert.[17] The later Rigvedic Sarasvati is only in the post-Rig Vedic Brahmanas said to disappear in the sands. According to Kocchar the Ganga and Yamuna were small streams in the vicinity of the Harut River. When the Vedic people moved east into Punjab, they named the new rivers they encountered after the old rivers they knew from Helmand, and the Vinasana Sarasvati may correspond with the Ghaggar-Hakra river.[109][104]

Romila Thapar has said the identification of the Ghaggar with the Sarasvati, is controversial. Furthermore, the early references to the Sarasvati could be the Haraxvati plain in Afghanistan. The identification with the Ghaggar is problematic as the Sarasvati is said to cut it's way through high mountains, which is not the landscape of the Ghaggar.[18]

Contemporary politico-religious meaning

Drying-up and dating of the Vedas

The Vedic and Puranic statements about the drying-up and diving-under of the Sarasvati have been used as a reference point for the dating of the Harappan civilisation and the Vedic culture.[3] Some see these texts as evidence for an earlier dating of the Rig Veda, identifying the Sarasvati with the Ghaggar-Hakra River, rejecting the Indo-Aryan migrations theory, which postulates a migration at 1500 BCE.[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6]

Michel Danino places the composition of the Vedas in the third millennium BCE, a millennium earlier than the conventional dates.[115] Danino notes that accepting the Rig Veda accounts as factual descriptions, and dating the drying up late in the third millennium, are incompatible.[115] According to Danino, this suggests that the Vedic people were present in northern India in the third millennium BCE,[116] a conclusion which is controversial amongst professional archaeologists.[115] Danino states that there is an absence of "any intrusive material culture in the Northwest during the second millennium BCE,"[115][lower-alpha 17] a biological continuity in the skeletal remains,[115][lower-alpha 6] and a cultural continuity. Danino then states that if the "testimony of the Sarasvati is added to this, the simplest and most natural conclusion is that the Vedic culture was present in the region in the third millennium."[23]

Danino acknowledges that this asks for "studying its tentacular ramifications into linguistics, archaeoastronomy, anthropology and genetics, besides a few other fields".[23]

Annette Wilke notes that the "historical river" Sarasvati was a "topographically tangible mythogeme", which was already reduced to a "small, sorry tickle in the desert", by the time of composition of the Hindu epics. These post-Vedic texts regularly talk about drying up of the river, and start associating the goddess Sarasvati with language, rather than the river.[9]

Michael Witzel also notes that the Rig Veda indicates that the Sarswati "had already lost its main source of water supply and must have ended in a terminal lake (samudra)."[10][lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2]

Identification with the Indus Valley Civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (Harrapan Civilisation), which is named after the Indus, was largely located on the banks of and in the proximity of the Ghaggar-Hakra fluvial system.[122]

The Indus Valley Civilisation is sometimes called the "Sarasvati culture", the "Sarasvati Civilization", the "Indus-Sarasvati Civilization" or the "Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization", as it is theorised that the civilisation flourished on banks of the Sarasvati river, along with the Indus.[20][21][22] Danino notes that the dating of the Vedas to the third millennium BCE coincides with the mature phase of the Indus Valley civilisation,[115] and that it is "tempting" to equate the Indus Valley and Vedic cultures.[23]

Romila Thapar points out that an alleged equation of the Indus Valley civilization and the carriers of Vedic culture stays in stark contrast to not only linguistic, but also archeological evidence. She notes that the essential characteristics of Indus valley urbanism, such as planned cities, complex fortifications, elaborate drainage systems, the use of mud and fire bricks, monumental buildings, extensive craft activity, are completely absent in the Rigveda. Similarly the Rigveda lacks a conceptual familiarity with key aspects of organized urban life (e.g. non-kin labour, facets or items of an exchange system or complex weights and measures) and doesn't mention objects found in great numbers at Indus Valley civilization sites like terracotta figurines, sculptural representation of human bodies or seals.[24]

Revival

In 2015, Reuters reported that "members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh believe that proof of the physical existence of the Vedic river would bolster their concept of a golden age of Hindu India, before invasions by Muslims and Christians." The Bharatiya Janata Party Government had therefore ordered archaeologists to search for the river.[123]

According to the government of Indian state of Haryana, research and satellite imagery of the region has confirmed to have found the lost river when water was detected during digging of the dry river bed at Yamunanagar. The government constituted Saraswati Heritage Development Board (SHDB) had conducted a trial run on 30 July 2016 filling the river bed with 100 cusecs of water which was pumped into a dug-up channel from tubewells at Uncha Chandna village in Yamunanagar. The water is expected to fill the channel until Kurukshetra, a distance of 40 kilometres. Once confirmed that there is no obstructions in the flow of the water, the government proposes to flow in another 100 cusecs after a fortnight. There also are plans to build three dams on the river route to keep it flowing perennially.[124]

Criticism

Ashoke Mukherjee (2001), is critical of the attempts to identify the Rigvedic Sarasvati. Mukherjee notes that many historians and archaeologists, both Indian and foreign, concluded that the word "Sarasvati" (literally "being full of water") is not a noun, a specific "thing". However, Mukherjee believes that "Sarasvati" is initially used by the Rig Vedic people as an adjective to the Indus as a large river and later evolved into a "noun". Mukherjee concludes that the Vedic poets had not seen the palaeo-Sarasvati, and that what they described in the Vedic verses refers to something else. He also suggests that in the post-Vedic and Puranic tradition the "disappearance" of Sarasvati, which to refers to "[going] under [the] ground in the sands", was created as a complementary myth to explain the visible non-existence of the river.[65]

See also

- Brahmavarta

- Drishadwati River

- Sapta Sindhu

- Saraswati - goddess

- Indus River

- Saraswat Brahmins

- Triveni Sangam

- Michel Danino - The lost River

- Sarasvati Pushkaram

Notes

- Witzel: "The autochthonous theory overlooks that RV 3.33206 already speaks of a necessarily smaller Sarasvatī: the Sudås hymn 3.33 refers to the confluence of the Beas and Sutlej (Vipåś, Śutudrī). This means that the Beas had already captured the Sutlej away from the Sarasvatī, dwarfing its water supply. While the Sutlej is fed by Himalayan glaciers, the Sarsuti is but a small local river depending on rain water.

In sum, the middle and later RV (books 3, 7 and the late book, 10.75) already depict the present day situation, with the Sarasvatī having lost most of its water to the Sutlej (and even earlier, much of it also to the Yamunå). It was no longer the large river it might have been before the early Rgvedic period.[120] - Witzel further notes: "If the RV is to be located in the Panjab, and supposedly to be dated well before the supposed 1900 BCE drying up of the Sarasvatī, at 4000-5000 BCE (Kak 1994, Misra 1992), the text should not contain evidence of the domesticated horse (not found in the subcontinent before c. 1700 BCE, see Meadow 1997,1998, Anreiter 1998: 675 sqq.), of the horse drawn chariot (developed only about 2000 BCE in S. Russia, Anthony and Vinogradov 1995, or Mesopotamia), of well developed copper/bronze technology, etc."[121]

- Giosan (2012): "Numerous speculations have advanced the idea that the Ghaggar-Hakra fluvial system, at times identified with the lost mythical river of Sarasvati (e.g., 4, 5, 7, 19), was a large glacier fed Himalayan river. Potential sources for this river include the Yamuna River, the Sutlej River, or both rivers. However, the lack of large-scale incision on the interfluve demonstrates that large, glacier-fed rivers did not flow across the Ghaggar-Hakra region during the Holocene [....] The present Ghaggar-Hakra valley and its tributary rivers are currently dry or have seasonal flows. Yet rivers were undoubtedly active in this region during the Urban Harappan Phase. We recovered sandy fluvial deposits approximately 5;400 y old at Fort Abbas in Pakistan (SI Text), and recent work (33) on the upper Ghaggar-Hakra interfluve in India also documented Holocene channel sands that are approximately 4;300 y old. On the upper interfluve, fine-grained floodplain deposition continued until the end of the Late Harappan Phase, as recent as 2,900 y ago (33) (Fig. 2B). This widespread fluvial redistribution of sediment suggests that reliable monsoon rains were able to sustain perennial rivers earlier during the Holocene and explains why Harappan settlements flourished along the entire Ghaggar-Hakra system without access to a glacier-fed river."[12]

- The Helmand river historically, besides Avestan Haetumant, bore the name Haraxvaiti, which is the Avestan form cognate to Sanskrit Sarasvati.

- According to David Anthony, the Yamna culture was the "Urheimat" of the Indo-Europeans at the Pontic steppes.[110] From this area, which already included various subcultures, Indo-European languages spread west, south and east starting around 4,000 BCE.[111] These languages may have been carried by small groups of males, with patron-client systems which allowed for the inclusion of other groups into their cultural system.[110] Eastward emerged the Sintashta culture (2100–1800 BCE), from which developed the Andronovo culture (1800–1400 BCE). This culture interacted with the BMAC (2300–1700 BCE); out of this interaction developed the Indo-Iranians, which split around 1800 BCE into the Indo-Aryans and the Iranians.[112] The Indo-Aryans migrated to the Levant, northern India, and possibly south Asia.[113]

- The migration into northern India was not a large-scale immigration, but may have consisted of small groups,[114] which were genetically diverse. Their culture and language spread by the same mechanisms of acculturalisation, and the absorption of other groups into their patron-client system.[110]

- See Witzel (1984)[38] for discussion; for maps (1984) of the area, p. 42 sqq.

- While the first translation takes a tatpurusha interpretation of síndhumātā, the word is actually a bahuvrihi. Hans Hock (1999) translates síndhumātā as a bahuvrihi, giving the second translation. A translation as a tatpurusha ("mother of rivers", with sindhu still with its generic meaning) would be less common in RV speech.

- RV 7.95.1-2:

- "This stream Sarasvati with fostering current comes forth, our sure defence, our fort of iron.

- As on a chariot, the flood flows on, surpassing in majesty and might all other waters.

- Pure in her course from mountains to the ocean, alone of streams Sarasvati hath listened.

- Thinking of wealth and the great world of creatures, she poured for Nahusa her milk and fatness."

- Puri and Verma (1998) argued that the present-day Tons River was the ancient upper-part of the Ghaggar-Hakra river, identified with the Sarasvati river by them. The Ghaggar-Haggar would then had been fed with Himalayan glaciers, which would make it the mighty river described in the Vedas. The terrain of this river contains pebbles of quartzite and metamorphic rocks, while the lower terraces in these valleys do not contain such rocks.[88] However, recent studies show that Bronze Age sediments from the glaciers of the Himalayas are missing along the Ghaggar-Hakra, indicating that the river did not or no longer have its sources in the high mountains.[89]

- According to Misra, there are several dried out river beds (paleochannels) between the Sutlej and the Yamuna, some of them two to ten kilometres wide. They are not always visible on the ground because of excessive silting and encroachment by sand of the dried out river channels.[90]

According to Pal, the course of the Sutlej suggests that "the Satluj periodically was the main tributary of the Ghaggar and that subsequently the tectonic movements may have forced the Satluj westward and the Ghaggar dried." At Ropar the Sutlej river suddenly turns sharply away from the Ghaggar. The narrow Ghaggar river bed itself is becoming suddenly wider at the conjunction where the Sutlej should have met the Ghaggar river. There also is a major paleochannel between the turning point of the Sutlej and where the Ghaggar river bed widens.[91][92]

There are no Harappan sites on the Sutlej in its present lower course, only in its upper course near the Siwaliks, and along the dried up channel of the ancient Sutlej,[93] which may suggest that the Sutlej did flow into the Ghaggar-Hakra at that time. - Raikes (1968) and Suraj Bhan (1972, 1973, 1975, 1977) have argued, based on archaeological, geomorphic and sedimentological research, that the Yamuna may have flowed into the Sarasvati during Harappan times.[94] According to Misra, the Yamuna may have flowed into the Sarasvati river through the Chautang or the Drishadvati channel, since many Harappan sites have been discovered on these dried out river beds.[95] There are no Harappan sites on the present Yamuna river, but there are, however, Painted Gray Ware (1000 - 600 BC) sites along the Yamuna channel, showing that the river must then have flowed in the present channel.[96]

- According to Lal, who supports the Indigenous Aryans theory, the disappearance of the river may additionally have been caused by earthquakes which may have led to the redirection of its tributaries.[99]

- According to geologists Puri and Verma a major seismic activity in the Himalayan region caused the rising of the Bata-Markanda Divide. This resulted in the blockage of the westward flow of Ghaggar-Hakra forcing the water back. Since the Yamunā Tear opening was not far off, the blocked water exited from the opening into the Yamunā system.[100] According to Mitra and Bhadu, active faults are present in the region, and lateral and vertical tectonic movements have frequently diverted streams in the past. The Ghaggar-Hakra may have migrated westward due to such uplift of the Aravallis.[101]

- Giosan et al. (2012, pp. 1688, 1689):

- "Contrary to earlier assumptions that a large glacier-fed Himalayan river, identified by some with the mythical Sarasvati, watered the Harappan heartland on the interfluve between the Indus and Ganges basins, we show that only monsoonal-fed rivers were active there during the Holocene." (Giosan et al. 2012, p. 1688)

- "Numerous speculations have advanced the idea that the Ghaggar-Hakra fluvial system, at times identified with the lost mythical river of Sarasvati (e.g., 4, 5, 7, 19), was a large glacierfed Himalayan river. Potential sources for this river include the Yamuna River, the Sutlej River, or both rivers. However, the lack of large-scale incision on the interfluve demonstrates that large, glacier-fed rivers did not flow across the Ghaggar-Hakra region during the Holocene." (Giosan et al. 2012, p. 1689)

- Valdiya (2013) dispute this, arguing that it was a large perennial river draining the high mountains as late as 3700–2500 years ago.

- Michael Witzel points out that this is to expected from a mobile society, but that the Gandhara grave culture is a clear indication of new cultural elements.[117] Michaels points out that there are linguistic and archaeological data that shows a cultural change after 1750 BCE,[118] and Flood notices that the linguistic and religious data clearly show links with Indo-European languages and religion.[119]

References

- Danino 2010, p. 260.

- Kinsley 1998, p. 10, 55-57.

- "Sarasvati | Hindu deity". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Witzel (2012, pp. 74, 125, 133): "It can easily be understood, as the Sarasvatī, the river on earth and in the nighttime sky, emerges, just as in Germanic myth, from the roots of the world tree. In the Middle Vedic texts, this is acted out in the Yātsattra... along the Rivers Sarasvatī and Dṛṣadvatī (northwest of Delhi)..."

- Vedic River Sarasvati and Hindu Civilization, edited by S. Kalyanaraman (2008), ISBN 978-81-7305-365-8 PP.308

- Mythical Saraswati River | "The work on delineation of entire course of Sarasvati River in North West India was carried out using Indian Remote Sensing Satellite data along with digital elevation model. Satellite images are multi-spectral, multi-temporal and have advantages of synoptic view, which are useful to detect palaeochannels. The palaeochannels are validated using historical maps, archaeological sites, hydro-geological and drilling data. It was observed that major Harappan sites of Kalibangan (Rajasthan), Banawali and Rakhigarhi (Haryana), Dholavira and Lothal (Gujarat) lie along the River Saraswati." — Department of Space, Government of India.

- "Saraswati – The ancient river lost in the desert" | A.V.Shankaran.

- Wilke 2011.

- Wilke 2011, pp. 310–311

- Witzel 2001, p. 93.

- Mukherjee 2001, p. 2, 8-9.

- Giosan, L.; et al. (2012). "Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan Civilization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 109 (26): E1688–E1694. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E1688G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112743109. PMC 3387054. PMID 22645375.

- Maemoku, Hideaki; Shitaoka, Yorinao; Nagatomo, Tsuneto; Yagi, Hiroshi (2013), "Geomorphological Constraints on the Ghaggar River Regime During the Mature Harappan Period", in Giosan, Liviu; Fuller, Dorian Q.; Nicoll, Kathleen; Flad, Rowan K.; Clift, Peter D. (eds.), Climates, Landscapes, and Civilizations, American Geophysical Union Monograph Series 198, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-118-70443-1

- Clift, Peter D.; Carter, Andrew; Giosan, Liviu; Durcan, Julie (2012). "U-Pb zircon dating evidence for a Pleistocene Sarasvati River and capture of the Yamuna River". Geology. 40 (3): 211–214. Bibcode:2012Geo....40..211C. doi:10.1130/g32840.1.

- Singh 2017.

- Chatterjee, Anirban; Ray, Jyotiranjan S.; Shukla, Anil D.; Pande, Kanchan (20 November 2019). "On the existence of a perennial river in the Harappan heartland". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 17221. Bibcode:2019NatSR...917221C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53489-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6868222. PMID 31748611.

- Kochhar, Rajesh (1999), "On the identity and chronology of the Ṛgvedic river Sarasvatī", in Roger Blench; Matthew Spriggs (eds.), Archaeology and Language III; Artefacts, languages and texts, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-10054-0

- Romila Thapar (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Sarasvati

- Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 137–8. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- Charles Keith Maisels (16 December 2003). "The Indus/'Harappan'/Sarasvati Civilization". Early Civilizations of the Old World: The Formative Histories of Egypt, The Levant, Mesopotamia, India and China. Routledge. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-134-83731-1.

- Denise Cush; Catherine A. Robinson; Michael York (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Psychology Press. p. 766. ISBN 978-0-7007-1267-0.

- Danino 2010, p. 258.

- Romila Thapar (2002). Early India. Penguin Books. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-1430-2989-2.

- e.g. 7.96.4, 10.66.5

- Mayrhofer, EWAia, s.v. Saraswatī as a common noun in Classical Sanskrit (again per M-W) means a region abounding in pools and lakes, the river of that name, or any river, especially a holy one. Like its cognates Welsh hêl, heledd ‘river meadow’ and Greek ἕλος (hélos) ‘swamp’; the root is otherwise often connected with rivers (also in river names, such as Sarayu or Susartu); the suggestion has been revived in the connection of an "out of India" argument, N. Kazanas, "Rig-Veda is pre-Harappan", p. 9.

- by Lommel (1927); Lommel, Herman (1927), Die Yašts des Awesta, Göttingen-Leipzig: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht/JC Hinrichs

- Manu (2004). Olivelle, Patrick, ed. The Law Code of Manu. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19280-271-2.

- Bridget Allchin, Raymond Allchin, The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan, Cambridge University Press, 1982, P.358.

- Ludvík 2007, p. 11

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony; Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1912). Vedic Index of names and subjects. 2. London: Murray. p. 434. OCLC 1014995385.

- translation by Sri Aurobindo, op.cit.

- 1.3, 13, 89, 164; 10.17, 30, 64, 65, 66, 75, 110, 131, 141

- K.R. Jayaswal, Hindu Polity, pp. 12-13

- Pancavimsa Brahmana, Jaiminiya Upanisad Brahmana, Katyayana Srauta Sutra, Latyayana Srauta; Macdonell and Keith 1912

- Asvalayana Srauta Sutra, Sankhayana Srauta Sutra; Macdonell and Keith 1912, II: 55

- Griffith, p.492

- Witzel 1984.

- D.S. Chauhan in Radhakrishna, B.P. and Merh, S.S. (editors): Vedic Saraswati 1999. According to this reference, 44 asvins may be over 2,600 km

- Bhargava, Sudhir (20–22 November 2009). Location of Brahmavarta and Drishadwati river is important to find earliest alignment of Saraswati river. Saraswati river – a perspective. organised by: Saraswati Nadi Shodh Sansthan, Haryana. Kurukshetra: Kurukshetra University. pp. 114–117.

- Mhb. 3.82.111; 3.130.3; 6.7.47; 6.37.1-4., 9.34.81; 9.37.1-2

- Mbh. 3.80.118

- Mbh. 3.88.2

- Haigh, Martin. "Haigh, M. 2011. Interpreting the Sarasvati Tirthayatra of Shri Balarāma. Itihas Darpan, Research Journal of Akhil Bhartiya Itihas Sankalan Yojana, ABISY (New Delhi), 16, 2, pp.179-193, [ISSN: 0974-3065]" – via www.academia.edu. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The journey of Jagannath from India to Egypt: The Untold Saga of the Kussites - Graham Hancock Official Website".

- org, Richard MAHONEY - r dot mahoney at indica-et-buddhica dot. "INDOLOGY - Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization (c. 3000 B.C.)". indology.info.

- Studies in Proto-Indo-Mediterranean culture, Volume 2, page 398

- D.S. Chauhan in Radhakrishna, B.P. and Merh, S.S. (editors): Vedic Saraswati, 1999, p.35-44

- compare also with Yajurveda 34.11, D.S. Chauhan in Radhakrishna, B.P. and Merh, S.S. (editors): Vedic Saraswati, 1999, p.35-44

- Eck p. 149

- Eck 2012, p. 147.

- Manusmriti 2.17-18

- Eck 2012, p. 145.

- Eck 2012, p. 148.

- Ludvík 2011, p. 1

- At the Three Rivers TIME, 23 February 1948

- Eck p. 145

- Eck p. 220

- Ludvík (2007, p. 85): "The Sarasvatī river, which, according to Witzel,... personifies the Milky Way, falls down to this world at Plakṣa Prāsarvaṇa, "the world tree at the center of heaven and earth," and flows through the land of the Kurus, the center of this world."

- Wilke (2011, p. 310, note 574): "Witzel suggests that Sarasvatī is not an earthly river, but the Milky Way that is seen as a road to immortality and heavenly after-life. In `mythical logic,' as outlined above, the two interpretations are not however mutually exclusive. There are passages which clearly suggest a river."

- Pushpendra K. Agarwal; Vijay P. Singh (16 May 2007). Hydrology and Water Resources of India. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 311–2. ISBN 978-1-4020-5180-7.

- Giosan et al. 2012.

- Darian 2001, p. 58.

- Darian p. 59

- Mukherjee 2001, p. 2, 6-9.

- Griffith

- S. Kalyanaraman (ed.), Vedic River Sarasvati and Hindu Civilization, ISBN 978-81-7305-365-8 PP.96

- J. Shaffer, in: J. Bronkhorst & M. Deshpande (eds.), Aryans and Non-Non-Aryans, Evidence, Interpretation and Ideology. Cambridge (Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora 3) 1999

- Valdiya, K. S. (1 January 2002). Saraswati: The River that Disappeared. Indian Space Research Organization. p. 23. ISBN 9788173714030.

- Stein, Aurel (1942). "A Survey of Ancient Sites along the "Lost" Sarasvati River". The Geographical Journal. 99 (4): 173–182. doi:10.2307/1788862. JSTOR 1788862.

- Gaur, R. C. (1983). Excavations at Atranjikhera, Early Civilization of the Upper Ganga Basin. Delhi.

- Darian p. 58

- "Proceedings of the second international symposium on the management of large rivers for fisheries: Volume II". Fao.org. 14 February 2003. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Mughal, M. R. Ancient Cholistan. Archaeology and Architecture. Rawalpindi-Lahore-Karachi: Ferozsons 1997, 2004

- J. K. Tripathi et al., "Is River Ghaggar, Saraswati? Geochemical Constraints," Current Science, Vol. 87, No. 8, 25 October 2004

- "Press Information Bureau English Releases". Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- PTI. "Government-constituted expert committee finds Saraswati river did exist". Indian Express. PTI. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Prasad, R.U.S. (2017). River and Goddess Worship in India: Changing Perceptions and Manifestations of Sarasvati. Routledge Hindu Studies Series. Taylor & Francis. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-351-80654-1. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Indische Alterthumskunde

- Sacred Books of the East, 32, 60

- Oldham 1893 pp.51–52

- Feuerstein, Georg; Kak, Subhash; Frawley, David (11 January 1999). In Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120816268 – via Google Books.

- Prasad 2017, p. 13.

- Danino 2010, p. 252.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- Gregory L. Possehl (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2.

- Valdiya, K.S. (2017). "Prehistoric River Saraswati, Western India". Society of Earth Scientists Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 6. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-44224-2. ISBN 978-3-319-44223-5. ISSN 2194-9204.

- Puri, V. M. K.; Verma, B.C. (1998). "Glaciological and Geological Source of Vedic Saraswati in the Himalayas". Itihas Darpan. IV (2): 7–36.

- Tripathi, J. K.; Bock, Barbara; Rajamani, V.; Eisenhauer, A. (October 2004). "Is River Ghaggar, Saraswati? Geochemical constraints". Current Science. 87 (8): 1141–1145.

- V. N. Misra in Gupta 1995, pp. 149–50

- Bryant 2001

- Yash Pal; et al. (1984). "Remote Sensing of the "Lost" Sarasvati River.". In Lal, B. B.; et al. (eds.). Frontiers of the Indus Civilization. p. 494.

Our studies thus show that the Satluj periodically was the main tributary of the Ghaggar and that subsequently the tectonic movements may have forced the Satluj westward and the Ghaggar dried.

- Gupta, S. P. (1999). Pande G. C.; D.P. Chattophadhyaya (eds.). The dawn of Indian civilization. History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. I. New Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilizations.

- V. N. Misra in Gupta 1995, p. 149

- V. N. Misra in Gupta 1995, p.155

- V. N. Misra in Gupta 1995, p. 153

- Hydrology and Water Resources of India By Sharad K. Jain, Pushpendra K. Agarwal, Vijay P. Singh

- The ancient Indus Valley: new perspectives By Jane McIntosh

- Lal 2002, p.24

- Puri and Verma 1998, Glaciological and geological source of Vedic Saraswati in the Himalayas.

- D. S. Mitra & Balram Bhadu (10 March 2012). "Possible contribution of River Saraswati in groundwater aquifer system in western Rajasthan, India" (PDF). Current Science. 102 (5).

- Giosan et al. 2012, p. 1693.

- Malavika Vyawahare (29 November 2017), New study challenges existence of Saraswati river, says it was Sutlej’s old course, HindustanTimes

- Rajesh Kocchar, The rivers Sarasvati: Reconciling the sacred texts, blog post based on The Vedic People: Their History and Geography.

- Kochhar 2012, p. 263.

- Prasad 2017, p. 42.

- Prasad, R.U.S. (2017). River and Goddess Worship in India: Changing Perceptions and Manifestations of Sarasvati. Routledge Hindu Studies Series. Taylor & Francis. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-351-80654-1. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Klaus, K. Die altindische Kosmologie, nach den Brāhmaṇas dargestellt. Bonn 1986; Samudra, XXIII Deutscher Orientalistentag Würzburg, ZDMG Suppl. Volume VII, Stuttgart 1989, 367-371

- Kochhar, Rajesh (1999), "On the identity and chronology of the Ṛgvedic river Sarasvatī", in Roger Blench; Matthew Spriggs (eds.), Archaeology and Language III; Artefacts, languages and texts, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-10054-0

- Anthony 2007.

- Beckwith 2009, p. 29.

- Anthony 2007, p. 408.

- Beckwith 2009.

- Witzel 2005, p. 342-343.

- Danino 2010, p. 256.

- Danino 2010, p. 256, 258.

- Witzel 2005.

- Michaels 2004, p. 33.

- Flood 1996, p. 33.

- Witzel 2001, p. 81.

- Witzel 2001, p. 31.

- Jayant K. Tripathi; Barbara Bock; V. Rajamani; A. Eisenhauer (25 October 2004). "Is River Ghaggar, Saraswati? Geochemical constraints" (PDF). Current Science. 87 (8).

- Rupam Jain Nair, Frank Jack Daniel (12 October 2015). "Special Report: Battling for India's soul, state by state". Rueters. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Zee Media Bureau (6 August 2016). "'Lost' Saraswati river brought 'back to life'". Zee Media. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

Sources

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World, Princeton University PressCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009), Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1400829941, retrieved 30 December 2014CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bryant, Edwin (2001), The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513777-4

- Danino, Michel (2010), The Lost River - On the trail of the Sarasvati, Penguin Books India

- Darian, Steven G. (2001), "5.Ganga and Sarasvati: The Transformation of Myth", The Ganges in Myth and History, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 978-81-208-1757-9

- Eck, Diana L. (2012), India: A Sacred Geography, Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony, ISBN 978-0-385-53191-7

- Clift; et al. (2012), "U-Pb zircon dating evidence for a Pleistocene Sarasvati River and capture of the Yamuna River", Geology, 40 (3): 211–214, Bibcode:2012Geo....40..211C, doi:10.1130/g32840.1

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press

- Giosan; et al. (2012), "Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilization", PNAS, 109 (26): E1688–E1694, Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E1688G, doi:10.1073/pnas.1112743109, PMC 3387054, PMID 22645375

- Gupta, S.P. (ed.). 1995. The lost Saraswati and the Indus Civilization. Kusumanjali Prakashan, Jodhpur.

- Hock, Hans (1999) Through a Glass Darkly: Modern "Racial" Interpretations vs. Textual and General Prehistoric Evidence on Arya and Dasa/Dasyu in Vedic Indo-Aryan Society." in Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia, ed. Bronkhorst & Deshpande, Ann Arbor.

- Keith and Macdonell. 1912. Vedic Index of Names and Subjects.

- Kinsley, David (1998), Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 978-81-208-0394-7

- Kochhar, Rajesh, 'On the identity and chronology of the Ṛgvedic river Sarasvatī' in Archaeology and Language III; Artefacts, languages and texts, Routledge (1999), ISBN 0-415-10054-2.

- Kochhar, Rajesh (2012), "On the identity and chronology of the Ṛgvedic river Sarasvatī", Archaeology and Language III; Artefacts, languages and texts, Routledge

- Lal, B.B. 2002. The Saraswati Flows on: the Continuity of Indian Culture. New Delhi: Aryan Books International

- Ludvík, Catherine (2007), Sarasvatī, Riverine Goddess of Knowledge: From the Manuscript-carrying Vīṇā-player to the Weapon-wielding Defender of the Dharma, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-15814-6

- Michaels, Axel (2004), Hinduism. Past and present, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press

- Mukherjee, Ashoke (2001), "RIGVEDIC SARASVATI: MYTH AND REALITY" (PDF), Breakthrough, Breakthrough Science Society, 9 (1)

- Oldham, R.D. 1893. The Sarsawati and the Lost River of the Indian Desert. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1893. 49-76.

- Puri, VKM, and Verma, BC, Glaciological and Geological Source of Vedic Sarasvati in the Himalayas, New Delhi, Itihas Darpan, Vol. IV, No.2, 1998 Glaciological and geological source of Vedic Sarasvati in the Himalayas

- Radhakrishna, B.P. and Merh, S.S. (editors): Vedic Saraswati: Evolutionary History of a Lost River of Northwestern India (1999) Geological Society of India (Memoir 42), Bangalore. Review (on page 3) Review

- Shaffer, Jim G. (1995), "Cultural tradition and Palaeoethnicity in South Asian Archaeology", in George Erdosy (ed.), Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia, ISBN 978-3-11-014447-5

- Singh, Ajit (2017), "Counter-intuitive influence of Himalayan river morphodynamics on Indus Civilisation urban settlements", Nature Communications, 8 (1): 1617, Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.1617S, doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01643-9, PMC 5705636, PMID 29184098

- S. G. Talageri, The RigVeda - A Historical Analysis chapter 4

- Valdiya, K. S. (2002), Saraswati: The River That Disappeared, Universities Press (India), Hyderabad, ISBN 978-81-7371-403-0

- Valdiya, K.S. (2013), "The River Saraswati was a Himalayan-born river" (PDF), Current Science, 104 (1): 42

- Wilke, Annette (2011), Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018159-3

- Witzel, Michael (1984), Sur le chemin du ciel (PDF)

- Witzel, Michael (2001), "Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts" (PDF), Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, 7 (3): 1–93

- Witzel, Michael (2005), "Indocentrism", in Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie L. (eds.), TheE Indo-Aryan Controversy. Evidence and inference in Indian history, Routledge

- Witzel, Michael (2012), The Origins of the World's Mythologies, Oxford University Press

Further reading

- Chakrabarti, D. K., & Saini, S. (2009). The problem of the Sarasvati River and notes on the archaeological geography of Haryana and Indian Panjab. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

- Eck, Diana L. (2012), India: A Sacred Geography, Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony, ISBN 978-0-385-53191-7

- Ludvík, Catherine (2007), Sarasvatī, Riverine Goddess of Knowledge: From the Manuscript-carrying Vīṇā-player to the Weapon-wielding Defender of the Dharma, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-15814-6

- Danino, Michel (2010), The Lost River - On the trail of the Sarasvati, Penguin Books India

- An archaeological tour along the Ghaggar-Hakra River by Aurel Stein

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sarasvati River. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sarasvati River |

- Is River Ghaggar, Saraswati? by Tripathi, Bock, Rajamani, Eir

- Saraswati – the ancient river lost in the desert by A. V. Sankaran

- Sarasvati research and Education Trust

- Map "પ્રદેશ નદીનો તટપ્રદેશ (બેઝીન) સરસ્વતી (Regional River Basin: Saraswati Basin)". Narmada, Water Resources, Water Supply and Kalpsar Department.