Cebuano language

The Cebuano language (/sɛˈbwɑːnoʊ/), colloquially referred to by most of its speakers simply as Bisaya/Binisaya[8] is an Austronesian language spoken in the southern Philippines, namely in Central Visayas, western parts of Eastern Visayas and on the majority of Mindanao. The language originates from the island of Cebu, and is spoken primarily by various Visayan ethnolinguistic groups who are native to those areas, mainly the Cebuanos.[9] While Filipino (Tagalog) has the largest number of speakers of Philippine languages, Cebuano had the largest native language-speaking population in the Philippines until about the 1980s.[10] It is by far the most widely spoken of the Visayan languages, which are in turn part of the wider Philippine languages.

| Cebuano | |

|---|---|

| Cebuan,[1] Sebwano,[2] Visayan | |

| Sugbuanon, Bisayâ, Bisayâng Sugbuanon, Sinugbuanong Binisayâ, Sinibwano | |

| Pronunciation | /sɛˈbwɑːnoʊ/[3][4][5] |

| Native to | Philippines |

| Region | Central Visayas, eastern Negros Occidental, western parts of Eastern Visayas, and most parts of Mindanao |

| Ethnicity | Cebuano |

Native speakers | 16 million (2005)[6] |

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | ceb |

| ISO 639-3 | ceb |

| Glottolog | cebu1242[7] |

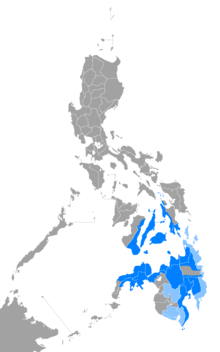

Cebuano-speaking area in the Philippines | |

The English translation is Visayan, which should not be confused with other Visayan languages.

It is the lingua franca of the Central Visayas, western parts of Eastern Visayas, some western parts of Palawan and most parts of Mindanao. The name Cebuano is derived from the island of Cebu, which is the Urheimat or origin of the language.[11][12] Cebuano is also the prime language in Western Leyte, noticeably in Ormoc and other municipalities surrounding the city, though most of the residents in the area name the Cebuano language by their own demonyms such as "Ormocanon" in Ormoc and "Albuerahanon" in Albuera.[13] Cebuano is given the ISO 639-2 three-letter code ceb, but has no ISO 639-1 two-letter code. The Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino, the official regulating body of Philippine languages, spells the name of the language as Sebwano. Cebuano and its dialects (including Boholano) are also sometimes referred to as Cebuan (/sɛˈbuːən/ seh-BOO-ən), especially in linguistics, where it is one of the five primary branches of the Visayan languages.[14]

Distribution

Cebuano is spoken in the provinces of Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, Negros Oriental, northeastern Negros Occidental, (as well as the municipality of Hinoba-an and the cities of Kabankalan and Sipalay to a great extent, alongside Ilonggo), southern Masbate, many portions of Leyte, Biliran, parts of Samar, and most parts of Mindanao, the second largest island of the Philippines.[11] Furthermore, "a large portion of the urban population of Zamboanga, Davao, Surigao and Cotabato is Cebuano speaking".[11] Some dialects of Cebuano have different names for the language. Cebuano speakers from Cebu are mainly called "Cebuano" while those from Bohol are "Boholano". Cebuano speakers in Leyte identify their dialect as Kanâ meaning that (Leyte Cebuano or Leyteño). Speakers in Mindanao and Luzon refer to the language simply as Binisaya or Bisaya.[13]

Nomenclature

In common or everyday parlance, especially by those speakers from outside of the island of Cebu, Cebuano is more often referred to as Bisaya. Bisaya, however, may become a source of confusion as many other Visayan languages may also be referred to as Bisaya even though they are not mutually intelligible with speakers of what is referred to by linguists as Cebuano. Cebuano in this sense applies to all speakers of vernaculars mutually intelligible with the vernaculars of Cebu island, regardless of origin or location, as well as to the language they speak.

The term Cebuano (itself part of the Spanish colonial heritage, from "Cebu"+"ano", a Latinate calque) has garnered some objections. For example, generations of Cebuano speakers in northern Mindanao (Dipolog, Dapitan, Misamis Occidental and Misamis Oriental together with coastal areas of Butuan) say that their ancestry traces back to Cebuano speakers native to their place and not from immigrants or settlers from the Visayas. Furthermore, they ethnically refer to themselves as Bisaya and not Cebuano, and their language as Binisaya.[15]

History

Cebuano originates from the island of Cebu.[12] The language "has spread from its base in Cebu" to nearby islands[12] and also Bohol, eastern Negros, western and southern parts of Leyte and most parts of Mindanao, especially the northern, southern, and eastern parts of the large island.[11]

Cebuano was first documented in a list of vocabulary compiled by Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian explorer who was part of and documented Ferdinand Magellan's 1521 expedition.[16] Spanish missionaries started to write in the language during the early 18th century. As a result of the eventual 300-year Spanish colonial period, Cebuano contains many words of Spanish origin.

While there is evidence of a pre-Spanish writing system for the language, its use appears to have been sporadic. Spaniards recorded the Visayan script[17] which was called Kudlit-kabadlit by the natives.[18] The colonists erroneously called the ancient Filipino script "Tagalog letters", regardless of the language for which it was used. This script died out by the 17th century as it was gradually supplanted by the Latin script.

The language was heavily influenced by the Spanish language during the period of colonialism from 1565 to 1898. With the arrival of Spanish colonists, for example, a Latin-based writing system was introduced alongside a number of Spanish loanwords.[19] Due to the influence of the Spanish language, the number of vowel sounds also increased from three to five.

Phonology

Vowels

Below is the vowel system of Cebuano with their corresponding letter representation in angular brackets:[15][20][21]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| Mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | o ⟨o⟩ | |

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ |

- /a/ an open front unrounded vowel similar to English "father"

- /ɛ/ an open-mid front unrounded vowel similar to English "bed"

- /i/ a close front unrounded vowel similar to English "machine"

- /o/ a close-mid back rounded vowel similar to English "forty"

- /u/ a close back rounded vowel similar to English "flute"

Sometimes, ⟨a⟩ may also be pronounced as the open-mid back unrounded vowel /ʌ/ (as in English "gut"); ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩ as the near-close near-front unrounded vowel /ɪ/ (as in English "bit"); and ⟨o⟩ or ⟨u⟩ as the open-mid back rounded vowel /ɔ/ (as in English "thought") or the near-close near-back rounded vowel /ʊ/ (as in English "hook").[15]

During the precolonial and Spanish period, Cebuano had only three vowel phonemes: /a/, /i/ and /u/. This was later expanded to five vowels with the introduction of Spanish. As a consequence, the vowels ⟨o⟩ or ⟨u⟩, as well as ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩, are still mostly allophones. They can be freely switched with each other without losing their meaning (free variation); though it may sound strange to a native listener, depending on their dialect. The vowel ⟨a⟩ has no variations, though it can be pronounced subtly differently, as either /a/ or /ʌ/ (and very rarely as /ɔ/ immediately after the consonant /w/). Loanwords, however, are usually more conservative in their orthography and pronunciation (e.g. dyip, "jeepney" from English "jeep", will never be written or spoken as dyep).[15][22]

Consonants

For Cebuano consonants, all the stops are unaspirated. The velar nasal /ŋ/ occurs in all positions, including at the beginning of a word (e.g. ngano, "why"). The glottal stop /ʔ/ is most commonly encountered in between two vowels, but can also appear in all positions.[15]

Like in Tagalog, glottal stops are usually not indicated in writing. When indicated, it is commonly written as a hyphen or an apostrophe if the glottal stop occurs in the middle of the word (e.g. to-o or to'o, "right"). More formally, when it occurs at the end of the word, it is indicated by a circumflex accent if both a stress and a glottal stop occurs at the final vowel (e.g. basâ, "wet"); or a grave accent if the glottal stop occurs at the final vowel, but the stress occurs at the penultimate syllable (e.g. batà, "child").[23][24][25]

Below is a chart of Cebuano consonants with their corresponding letter representation in parentheses:[15][20][21][26]

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n̪ ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | |||||||

| Stop | p ⟨p⟩ | b ⟨b⟩ | t̪ ⟨t⟩ | d̪ ⟨d⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ɡ ⟨g⟩ | ʔ (see text) | |||

| Fricative | s̪ ⟨s⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | ||||||||

| Affricate | ||||||||||

| Approximant (Lateral) |

j ⟨y⟩ | w ⟨w⟩ | ||||||||

| l̪ ⟨l⟩ | ||||||||||

| Rhotic | ɾ̪~r̪ ⟨r⟩ | |||||||||

In certain dialects, /l/ ⟨l⟩ may be interchanged with /w/ ⟨w⟩ in between vowels and vice versa depending on the following conditions:[15]

- If ⟨l⟩ is in between ⟨a⟩ and ⟨u⟩/⟨o⟩, the vowel succeeding ⟨l⟩ is usually (but not always) dropped (e.g. lalum, "deep", becomes lawum or lawm).

- If ⟨l⟩ is in between ⟨u⟩/⟨o⟩ and ⟨a⟩, it is the vowel that is preceding ⟨l⟩ that is instead dropped (e.g. bulan, "moon", becomes buwan or bwan)

- If ⟨l⟩ is in between two like vowels, the ⟨l⟩ may be dropped completely and the vowel lengthened. For example, dala ("bring"), becomes da (/d̪aː/); and tulod ("push") becomes tud (/t̪uːd̪/).[15] Except if the l is in between closed syllables or is in the beginning of the penultimate syllable; in which case, the ⟨l⟩ is dropped along with one of the vowels, and no lengthening occurs. For example, kalatkat, "climb", becomes katkat (/ˈkatkat/ not /ˈkaːtkat/).

A final ⟨l⟩ can also be replaced with ⟨w⟩ in certain areas in Bohol (e.g. tambal, "medicine", becomes tambaw). In very rare cases in Cebu, ⟨l⟩ may also be replaced with ⟨y⟩ in between the vowels ⟨a⟩ and ⟨e⟩/⟨i⟩ (e.g. tingali, "maybe", becomes tingayi).[15]

In some parts of Bohol and Southern Leyte, /j/ ⟨y⟩ is also often replaced with d͡ʒ ⟨j/dy⟩ when it is in the beginning of a syllable (e.g. kalayo, "fire", becomes kalajo). It can also happen even if the ⟨y⟩ is at the final position of the syllable and the word, but only if it is moved to the initial position by the addition of the affix -a. For example, baboy ("pig") can not become baboj, but baboya can become baboja.[15]

All of the above substitutions are considered allophonic and do not change the meaning of the word.[15]

In rarer instances, the consonant ⟨d⟩ might also be replaced with ⟨r⟩ when it is in between two vowels (e.g. Boholano ido for standard Cebuano iro, "dog"), but ⟨d⟩ and ⟨r⟩ are not considered allophones,[15] though they may have been in the past.[27]

Stress

Stress accent is phonemic, so that dapít (adverb) means "near to a place," while dāpit (noun) means "place." dū-ol (verb) means "come near," while du-ól (adverb) means "near" or "close by."

Grammar

Vocabulary

Cebuano is a member of the Philippine languages. Early trade contact resulted in a large number of older loan words from other languages being embedded in Cebuano, like Sanskrit (e.g. sangka, "fight" and bahandi, "wealth", from Sanskrit sanka and bhānda respectively), and Arabic (e.g. salámat, "thanks"; hukom or hukm, "judge").[28]

It has also been influenced by thousands of words from Spanish, such as kurus [cruz] (cross), swerte [suerte] ("luck"), gwapa [guapa], ("beautiful"), merkado [mercado] ("market") and brilyante [brillante] ("brilliant"). It has several hundred loan words from English as well, which are altered to conform to the limited phonemic inventory of Cebuano: brislit (bracelet), hayskul (high school), syáping (shopping), bakwit (evacuate), and dráyber (driver). However, today, it is more common for Cebuanos to spell out those words in their original English form rather than with spelling that might conform to Cebuano standards.

Phrases

A few common phrases in Cebuano include:[29]

- How are you? (used as a greeting) - Kumusta?

- Good morning - Maayong buntag

- Good afternoon (specifically at 12:00 Noon up to 12:59 PM) - Maayong udto

- Good afternoon - Maayong hapon

- Good evening - Maayong gabii

- Good bye - Ayo-ayo ("Take care", formal), Adios (rare), Babay (informal, corruption of "Goodbye"), Amping ("Take care"), Hangtud sa sunod nga higayon ("Until next time")

- Thank you - Salamat

- Many thanks! - Daghang Salamat

- Thank you very much! - Daghang kaayong salamat

- You're welcome - Wala'y sapayan

- Do not (imperative) - Ayaw

- Don't know - Ambot

- Yes - O

- Maybe - Tingali, Basin

- No [30][31]

- Dili - for future verb negation ("will not", "does/do not", "not going to"); and negation of identity, membership, property, relation, or position ("[he/she/it/this/that] is not")

- Wala - for past and progressive verb negation ("have not", "did not"); and to indicate the absence of ("none", "nothing", "not have", "there is not")

- Who - Kinsa

- What - Unsa

- Where

- dein - where (past)

- Ása - where (present)

- Which - Hain

- When - Kanus-a

- How - Giunsa

Dialects

The de facto Standard Cebuano dialect (sometimes referred to as General Cebuano) is derived from the vernacular spoken in southeastern Cebu (also known as the Sialo dialect or the Carcar-Dalaguete dialect). It first gained prominence due to its adoption by the Catholic Church as the standard for written Cebuano. It retains the intervocalic /l/.[15] In contrast, the Urban Cebuano dialect spoken by people in Metro Cebu and surrounding areas is characterized by /l/ elision and heavily contracted words and phrases.[15] For example, waláy problema ("no problem") in Standard Cebuano can become way 'blema in Urban Cebuano.

Colloquialisms can also be used to determine the regional origin of the speaker. Cebuano-speaking people from Cagayan de Oro and Dumaguete, for example, say chada or tsada/patsada (roughly translated to the English colloquialism "awesome")[32] and people from Davao City say atchup which also translated to the same English context;[33] meanwhile Cebuanos from Cebu on the other hand say nindot or, sometimes, aníndot. However, this word is also commonly used in the same context in other Cebuano-speaking regions, in effect making this word not only limited in use to Cebu.

There is no standardized orthography for Cebuano, but spelling in print usually follow the pronunciation of Standard Cebuano, regardless of how it is actually spoken by the speaker. For example, baláy ("house") is pronounced /baˈl̪aɪ/ in Standard Cebuano and is thus spelled "baláy", even in Urban Cebuano where it is actually pronounced /ˈbaɪ/.[15]

Cebuano is spoken natively over a large area of the Philippines and thus has numerous regional dialects. It can vary significantly in terms of lexicon and phonology depending on where it is spoken.[15] Increasing usage of spoken English (being the primary language of commerce and education in the Philippines) has also led to the introduction of new pronunciations and spellings of old Cebuano words. Code-switching forms of English and Bisaya (Bislish) are also common among the educated younger generations.[34][35]

There are four main dialectal groups within Cebuano aside from the Standard Cebuano and Urban Cebuano. They are as follows:[36][37][38][39]

Boholano Cebuano

The Boholano dialect of Bohol shares many similarities with the southern form of the standard Cebuano dialect. It is also spoken in some parts of Siquijor. Boholano, especially as spoken in central Bohol, can be distinguished from other Cebuano variants by a few phonetic changes:

- The semivowel y is pronounced [dʒ]: iya is pronounced [iˈdʒa];

- Ako is pronounced as [aˈho];

- Intervocalic l is occasionally pronounced as [w] when following u or o: kulang is pronounced as [ˈkuwaŋ] (the same as Metro Cebu dialect).

Leyteño Cebuano

Southern Kana

Southern Kana is a dialect of both southern Leyte and Southern Leyte provinces; it is closest to the Mindanao Cebuano dialect at the southern area and northern Cebu dialect at the northern boundaries. Both North and South Kana are subgroups of Leyteño dialect. Both of these dialects are spoken in western and central Leyte and in the southern province, but the Boholano is more concentrated in Maasin City.

Speakers of these two dialects can be distinguished by their distinctive modification of /j/ into /dʒ/, as in the words ayaw (don't) is turned into ajaw; dayon (come in) - dajun; bayad(pay) -bajad. Like the Mindanao dialects, they are notable for their usage of a vocabulary containing archaic longer words like kalatkat ("climb") instead of katkat.

Northern Kana

North Kana (found in the northern part of Leyte), is closest to the variety of the language spoken in northern part of Leyte, and shows significant influence from Waray-Waray, quite notably in its pace which speakers from Cebu find very fast, and its more mellow tone (compared to the urban Cebu City dialect, which Kana speakers find "rough"). A distinguishing feature of this dialect is the reduction of /A/ prominent, but an often unnoticed feature of this dialect is the labialisation of /n/ and /ŋ/ into /m/, when these phonemes come before /p/ /b/ and /m/, velarisation of /m/ and /n/ into /ŋ/ before /k/ /ɡ/ and /ŋ/, and the dentalisation of /ŋ/ and /m/ into /n/ before /t/, /d/ and /n/ and sometimes, before vowels and other consonants as well.

The Northern Kana dialect generally contains less /l/ sounds than standard Cebuano. In between vowels /l/ is removed, and depending on what vowel chain follows, it may create a long vowel or have /y/ or /w/ take its place. (Elision)

Some words also hold different meanings, like how the word "ramāw"/"lamāw" refers to the meat of young coconut suspended in either coconut juice or sugared milk in N. Kana; while in Standard Cebuano, "lamāw" means "rice leftovers", which is "bahāw" in S. Kana and Mindanao Cebuano.

| Sugbu | Kana | Waray | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kan-on | Luto | Lutô | Cooked rice/maize |

| Kini/kiri | Kiri/kini | Ini | This |

| Kana | Kara'/kana | Iton | That |

| Dinhi/Diri | ari/dinhi/diri | Didi/Ngadi/Aadi/Dinhi | Here |

| Diha/Dinha | Dira/diha/dinha | Dida/Ngada/Aada | There |

| Bas/Balas | Bas/Balas | Baras | Soil/Sand |

| Alsa | Arsa | Alsa | To lift |

| Bulsa | Bursa | Bulsa |

Mindanao Cebuano

This is the variety of Cebuano spoken throughout most of Mindanao and it is the standard dialect of Cebuano in Northern Mindanao.

Local historical sources found in Cagayan de Oro indicates the early presence of Cebuano Visayans in the Misamis-Agusan coastal areas and their contacts with the Lumads and peoples of the Rajahnate of Butuan. Lumads refer to these Visayan groups as "Dumagat" ("people of the sea") as they came in the area seaborne. It became the lingua franca of precolonial Visayan settlers and native Lumads of the area, and particularly of the ancient Rajahnate of Butuan where Butuanon, a Southern Visayan language, was also spoken. Cebuano influence in Lumad languages around the highlands of Misamis Oriental and Bukidnon was furthered with the influx of Cebuano Visayan laborers and conscripts of the Spaniards from Cebuano areas of Visayas (particularly from Bohol) during the colonial period around the present-day region of Northern Mindanao. It has spread west towards the Zamboanga Peninsula, east towards Caraga, and south towards Bukidnon, Cotabato and the Davao Region in the final years of Spanish colonial rule.

Similar to the Sialo dialect of southeastern Cebu, it is distinctive in retaining /l/ sounds, long since considered archaic in Urban Cebuano. For example: bulan instead of buwan ("moon" or "month"), dalunggan instead of dunggan (ear), and halang instead of hang ("spicy").

Due to the influx of migrants (mostly from Western Visayas and Leyte) during the promotion of settlement in the highlands of Central Mindanao in the 1930s, vocabulary from other Visayan languages (predominantly Hiligaynon and Waray-Waray) have also been incorporated into Mindanao Cebuano. For example, the Hiligaynon sábat ("reply") is commonly used alongside Cebuano tubag, bulig alongside tábang ("help"), and Waray lutô alongside kan-on ("cooked rice"). Though, these influences are only limited to the speakers along the port area and Hiligaynon-speaking communities.

Davaoeño Cebuano

A branch of Mindanao Cebuano in Davao is also known as Davaoeño (not to be confused with the Davao variant of Chavacano which is called "Castellano Abakay"). Like the Cebuano-speakers of Luzon (Luzon Cebuano dialect), it contains some Tagalog vocabulary to a greater extent. Its grammar is somewhat in between the original Cebuano language and the Luzon Cebuano dialect. However, speakers from Davao City nowadays exhibits stronger Tagalog influence in their speech by substituting most Cebuano words with Tagalog ones. One characteristic is the practice of saying atà, derived from Tagalog yatà to denote uncertainty of a speaker's any aforementioned statements. For instance, "To-a man atà sa baláy si Manuel" instead of "To-a man tingáli sa baláy si Manuel". However, the word atà exists in Cebuano though it means " squid ink" (atà sa nukos).

Other examples include: Nibabâ ko sa dyip sa kanto, tapos miulî ko sa among baláy ("I got off the jeepney at the street corner, and then I went home") instead of Nináug ko sa dyip sa kanto, dayon miulî ko sa among baláy. The words babâ and naug mean "to disembark" or "to go down", while tapos and dayon mean "then"; the former is Tagalog, and the latter Cebuano. It also sometimes add some Bagobo and Mansakan vocabulary, like: Madayaw nga adlaw, amigo, kamusta ka? ("Good day, friend, how are you?", literally "Good morning/afternoon") rather than "Maayo nga adlaw, amigo, kamusta ka?" The words madayaw and maayo mean "good"; the former is Bagobo, and the latter Cebuano.

Negrense Cebuano

The Cebuano dialect in Negros is somewhat similar to the Standard Cebuano (spoken by the majority of the provincial areas of Cebu), with distinct Hiligaynon influences. It is distinctive in retaining /l/ sounds and longer word forms as well. It is the primary dialectal language of the entire province of Negros Oriental and northeastern parts of Negros Occidental (while the majority of the latter province and its bordered areas speaks Hiligaynon/Ilonggo), as well as some parts of Siquijor. Examples of Negrense Cebuano's distinction from other Cebuano dialects is the usage of the word maot instead of batî ("ugly"), alálay, kalálag instead of kalag-kalag (Halloween), kabaló/kahíbaló and kaágo/kaántigo instead of kabawó/kahíbawó ("know").

Other dialects

Luzon Cebuano

There is no specific Luzon dialect, as speakers of Cebuano in Luzon come from many different regions in Central Visayas and Mindanao. Cebuano-speaking people from Luzon in Visayas can be easily recognized primarily by their vocabulary which incorporates Tagalog words. Their accents and some aspects of grammar can also sometimes exhibit Tagalog influence. The dialect is sometimes colloquially known as "Bisalog" (a portmanteau of Tagalog and Binisaya).

Saksak Sinagol

The term saksak sinagol in context means "a collection of miscellaneous things" and literally "inserted mixture", thus those other few Cebuano-influenced regions that have a variety of regional languages uses this term to refer to their dialect with considerable incorporated Cebuano words. Example of these regions are places likes those in Masbate.

Examples

Numbers

Cebuano uses two numeral systems:

The native system (currently) is mostly used in counting the number of things, animate and inanimate, e.g. the number of horses, houses.

The spanish-derived system, on the other hand, is exclusively applied in monetary terminology and is also commonly used in counting from 11 and above.

| Number | Native Cebuano | Spanish-derived |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | walà | nulo, sero |

| 1 | usá | uno |

| 2 | duhá | dos |

| 3 | tuló | tres |

| 4 | upát | kwatro |

| 5 | limá | singko |

| 6 | unóm | says (sáyis) |

| 7 | pitó | site (siyéte) |

| 8 | waló | otso |

| 9 | siyám | nuybe (nuwébe) |

| 10 | napulò, pulò | dyes (diyés) |

| 11 | napúlog usá | onse |

| 12 | napúlog duhá | dose |

| 13 | napúlog tuló | trese |

| 14 | napúlog upát | katórse |

| 15 | napúlog limá | kinse |

| 16 | napúlog unóm | disesáys (diyésesáyis) |

| 17 | napúlog pitó | disesite |

| 18 | napúlog waló | diseotso |

| 19 | napúlog siyám | disenuybe |

| 20 | kawháan (kaduháan) | baynte (beyínte) |

| 21 | kawháag usá | baynte uno |

| 22 | kawháag duhá | baynte dos |

| 23 | kawháag tuló | baynte tres |

| 24 | kawháag upát | baynte kwatro |

| 25 | kawháag limá | bayntsingko (bayntesingko) |

| 30 | katló-an (katuló-an) | traynta (treyínta) |

| 40 | kap-atan (kaupátan) | kwarénta |

| 50 | kalím-an (kalimá-an) | singkwénta |

| 60 | kan-uman (ka-unóman) | saysénta (sesénta) |

| 70 | kapitó-an | seténta |

| 80 | kawaló-an | otsénta |

| 90 | kasiyáman | nobénta |

| 100 | usá ka gatós | siyén, sento (siyénto) |

| 200 | duhá ka gatós | doséntos (dosiyéntos) |

| 300 | tuló ka gatós | treséntos (tresiyéntos) |

| 400 | upát ka gatós | kwatroséntos (kwatrosiyéntos) |

| 500 | limá ka gatós | kinéntos (kiniyéntos) |

| 1,000 | usá ka libo | mil |

| 5,000 | limá ka libo | singko mil |

| 10,000 | usá ka laksà, napulò ka libo | dyes mil |

| 50,000 | limá ka laksà, kalím-an ka libo | singkwénta mil |

| 100,000 | napulò ka laksà, usá ka gatós ka líbo | siyén mil, siyénto mil |

| 1,000,000 | usá ka yukót | milyón |

| 1,000,000,000 | usá ka wakát | bilyón |

See also

Notes

- "Definition of Cebuan". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- The Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, the official regulating body of Philippine languages, spells the name of the language as Sebwano.

- "Definition of Cebuano". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "Definition of Cebu". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "Cebu (province)". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Cebuano at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Cebuano". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- The reference to the language as Binisaya is not encouraged by many linguists due to the many languages within the Visayan language group that may be confused with the term.

- "Cebuano". Ethnologue. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Ammon, Ulrich; Dittmar, Norbert; Mattheier, Klaus J.; Trudgill, Peter (2006). Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society. Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter. p. 2018. ISBN 9783110184181.

- Wolff 1972

- Wolff, John U. (2001). "Cebuano" (PDF). In Garry, Jane; Galvez Rubino, Carl R. (eds.). Facts About the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World's Major Languages, Past and Present. New York: H. W. Wilson.

- Pangan, John Kingsley (2016). Church of the Far East. Makati: St. Pauls. p. 19.

- Zorc, David Paul (1977). The Bisayan Dialects of the Philippines: Subgrouping and Reconstruction. Pacific Linguistics Series C - No. 44. Canberra, Australia: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. doi:10.15144/PL-C44. hdl:1885/146594. ISBN 0858831570.

- Endriga 2010

- "Cebuano language, alphabet and pronunciation". Omniglot.com. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- "Alphabets Des Philippines" (JPG). S-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Eleanor, Maria (16 July 2011). "Finding the "Aginid"". philstar.com. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- "Cebuano". www.alsintl.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- "Cebuano Phonetics and Orthography" (PDF). Dila. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Thompson, Irene (11 July 2013). "Cebuano". About World Languages. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Steinkrüger, Patrick O. (2008). "Hispanisation processes in the Philippines". In Stolz, Thomas; Bakker, Dik; Palomo, Rosa Salas (eds.). Hispanisation: The Impact of Spanish on the Lexicon and Grammar of the Indigenous Languages of Austronesia and the Americas. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 203–236. ISBN 9783110207231.

- Morrow, Paul (16 March 2011). "The basics of Filipino pronunciation: Part 2 of 3 • accent marks". Pilipino Express. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Nolasco, Ricardo M.D. Grammar notes on the national language (PDF). Fhl.digitalsolutions.ph.

- Schoellner, Joan; Heinle, Beverly D., eds. (2007). Tagalog Reading Booklet (PDF). Simon & Schister's Pimsleur. pp. 5–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Bollas, Abigail A. (2013), Comparative Analysis on the Phonology of Tagalog, Cebuano, and Itawis, University of the Philippines - Diliman

- Verstraelen, Eugene (1961). "Some further remarks about the L-feature". Philippine Studies. 9 (1): 72–77.

- Kuizon, Jose G. (1964). "The Sanskrit Loan-Words in the Cebuano-Bisayan Language". Asian Folklore Studies. 23 (1): 111–158. doi:10.2307/1177640. JSTOR 1177640.

- "Useful Cebuano phrases". Omniglot. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- "Wala / Dili". Learn Cebuano: Cebuano-Visayan Language Lessons. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- Curtis D. McFarland (2008). "Linguistic diversity and English in the Philippines". In Maria Lourdes S. Bautista & Kingsley Bolton (ed.). Philippine English: Linguistic and Literary. Hong Kong University Press. p. 137–138. ISBN 9789622099470.

- "10 Fun Facts about Cagayan de Oro". About Cagayan de Oro. 5 February 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "Atchup Boulevard Explained". www.ilovedavao.com. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Nissan, Ephraim (2012). "Asia at Both Ends: An Introduction to Etymythology, with a Response to Chapter Nine". In Zuckermann, Ghil‘ad (ed.). Burning Issues in Afro-Asiatic Linguistics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 9781443864626.

- Meierkord, Christiane (2012). Interactions Across Englishes: Linguistic Choices in Local and International Contact Situations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 209. ISBN 9780521192286.

- "Cebuano". Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Dingwall, Alastair (1994). Traveller's Literary Companion to South-East Asia. In Print Publishing, Limited. p. 372. ISBN 9781873047255.

- Blake, Frank R. (1905). "The Bisayan Dialects". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 26 (1905): 120–136. doi:10.2307/592885. JSTOR 592885.

- Gonzalez, Andrew (1991). "Cebuano and Tagalog: Ethnic Rivalry Redivivus". In Dow, James R. (ed.). Focus on Language and Ethnicity. Volume 2. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 115–116. ISBN 9789027220813.

References

- Endriga, Divine Angeli (2010). The Dialectology of Cebuano: Bohol, Cebu and Davao. 1st Philippine Conference Workshop on Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education held from February 18–20, 2010. Capitol University, Cagayan de Oro.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bunye, Maria V. R.; Yap, Elsa P. (1971a). Cebuano for Beginners. University of Hawaii Press. hdl:10125/62862.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bunye, Maria V. R.; Yap, Elsa P. (1971b). Cebuano Grammar Notes. University of Hawaii Press. hdl:10125/62863.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolff, John U. (1972). A Dictionary of Cebuano Visayan (PDF). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University, Southeast Asia Program and Linguistic Society of the Philippines. hdl:1813/11777. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2017 – via Gutenberg.ph.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Cebuano edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Cebuano. |

- Bansa.org Cebuano Dictionary

- Cebuano Dictionary

- Cebuano English Searchable Dictionary

- John U. Wolff, A Dictionary of Cebuano Visayan: Volume I, Volume II, searchable interface, Downloadable text at Project Gutenberg

- Ang Dila Natong Bisaya

- Lagda Sa Espeling Rules of Spelling (Cebuano)

- Language Links.org - Philippine Languages to the world - Cebuano Lessons

- Language Links.org - Philippine Languages to the World

- Online E-book of Spanish-Cebuano Dictionary, published in 1898 by Fr. Felix Guillén

- Cebuano dictionary

- Online bible, video and audio files, publications and other bible study material in Cebuano language