Zuism

| Zuism Sumerian-Mesopotamian Neopaganism | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Type | Neopagan new religious movement |

| Classification | Sumerian religion |

| Region | Mostly Iceland, central and northern Europe |

| Origin |

1980s (early informal groups), 2010 (Icelandic institutionalisation) Iceland |

| Members | 1,923 (Iceland 2018)[1] |

| Official website | http://zuism.is/ |

Zuism or Sumerian-Mesopotamian Neopaganism[note 1] define a modern Pagan religious movement based on the Sumerian religion (and later Mesopotamian religions which continued it),[3] and calls itself the "oldest religion, foundation of all major religions".[4] Modern Sumerian-Mesopotamian religious groups already existed since the 1980s;[5] however, the first institutional form of the movement was founded in Iceland in 2010 by Ólafur Helgi Þorgrímsson, and in 2013 Zuism was registered among the religions recognised by the Icelandic government.[3] After the mid-2010s, branches of the church were established in other countries of central and northern Europe.[3]

In late 2015 the Zuist Church of Iceland was taken over by a new leadership, under which the church was turned into a medium for a mass protest against the nationally mandated tax on religious membership; Icelanders began converting in large numbers as the new leadership promised that the tax received by the Zuist Church would have been used to refund the church members themselves.[6] After a legal struggle, in 2017 the original directors of the church were restored to power. They decided to maintain the previous leaders' principle of refunding church members,[7] and also to devolve funds to social welfare institutions.[8][9] Zuism has spread considerably in Iceland by attracting members among younger, internet-connected, less Christian generations of Icelanders.[10]

Terminology

Modern Sumerian-Mesopotamin religion has been known as "Zuism", "Sumerian-Mesopotamian Neopaganism" or "Sumerian-Mesopotamian Reconstructionism", "Babylonian Neopaganism" or "Babylonian Reconstructionism", and "Kaldanism" (which means "way of Chaldeans", Chaldea being a late term for Sumer). Among them, Zuism has become the most popular descriptor for the movement, by virtue of being the name under which the religion is recognised by Icelandic law.[5]

Zuism is defined as an international religious movement which intends to represent all the groups professing Sumerian-Mesopotamian religions. The Zuist Church of Iceland, the orgaisation recognised by the Icelandic government, has established branches throughout various countries and intends to be a platform for all Zuist believers. Many Zuists and Sumerian-Mesopotamian Neopagans are contributing to the development of the movement both within and outside the Zuist Church.[5]

The name "Zuism" originates from the Sumerian verb zu 𒍪, meaning "to know",[11] and is defined as a "way of knowledge", of knowing the appropriate modality of being human, in harmony with divinity. It is equated with the Greek term gnosis.[5] The term zu may also refer to the thunder-bird god of wisdom, Zû,[12] servant of Enlil.

Beliefs and practices

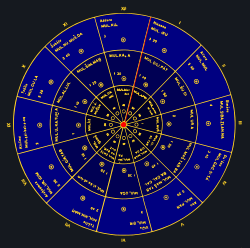

— The darkest-blue ring just around the centre are the constellations of the "Path of Enlil", constituting the northern or inner sky, with Enlil himself specifically identified as Mul.apin, Triangulum, the enclosure highlighted by the red line. Enlil's female, Ninlil, is the Mar.gid.da, the Great Chariot, in the same ring.[15]

— The lightest-blue ring are the constellations of the "Path of Enki", constituting the southern or outer sky, with Enki ("Lord of the Squared Earth") himself specifically identifies as Mul.iku, the Square of Pegasus, highlighted by the red line.[14]

— The medium-blue ring between the inner Path of Enlil and the outer Path of Enki is the "Path of An".[13]

Zuism is defined as the knowledge on how to appropriately stand in-between Heaven (𒀭 An or Dingir) and Earth (𒆠 Ki), by acting in accordance with the creative word (𒌓 utu) and the measures (𒈨 me) represented by the gods (𒀭 dingir), all constituting the energetic logos (𒆤 lil) of Heaven.[5]

Theology

Gods are held to be immortal beings, who are human-like and yet invisible to human eyes. They are potencies who guide the development of the universe. The four main divine beings are:[16] ① the universal god An/Dingir (literally "Heaven"/"God", astrally identified as the ecliptic north celestial pole encompassed by the coil of the constellation Draco, and with all the constellations spinning around it;[14][17] the Little Bear is his chariot, Mar.gid.da.an.na, the "Chariot of Heaven"[15]), ② Ki or Ninhursag (literally "Earth" or "Lady of the Mountain"), ③ Enki (literally "Lord of the Squared Earth", the god of water and craft, astrally identified as Aš.iku or Mul.iku, the "Field", that is the Square of Pegasus, and generally with the southern sky—called Path of Enki—, that is to say the circle farther from the north celestial pole An[14][13]) and ④ Enlil (literally "Lord of the Storm", the god of weather and thunder, identified as Mul.apin, the "Plough", that is the constellation Triangulum, and generally with the northern sky—called Path of Enlil—, that is to say the circle nearest to the north celestial pole An; his wife Ninlil, literally "Lady of the Storm", is Mar.gid.da, the "Chariot"[15][13]). Sky, earth, air and water are thus considered the fundamental elements of the cosmos.[16]

Lesser deities include[16] Nanna (the moon), Utu (the sun), Marduk (represented with a sword and a dragon, astrally identified as Jupiter,[18] and also associated with the north celestial pole An[19]), Nabu (god of writing and wisdom, astrally identified as Mercury[18]), Nergal (god of the underworld and plagues, astrally identified as Mars[18]), Ninurta (god of war and farming, astrally identified as Saturn[20]), Inanna (goddess of love, beauty, creativity and war; astrally identified as Venus[21]) and Dumuzi (shepherd god of death and resurrection, astrally identified as Aries[22]).

Ethics and scripture recitation

The universe is created by the gods through the word, utu (𒌓), and developed through the measures, me 𒈨.[23][16] The divine word (utu) which has performative power, is the power to create. By the words of the founders and earliest leaders, the "act of creation ... was accomplished through utterance of the divine word". The deity "had merely to make plans and pronounce the name of the thing to be created".[23] The measures (me) are "universal and unchangeable rules and laws that all beings are obliged to obey", which "keep the cosmos in continuous and harmonious operation and ... avoid confusion and conflict".[23]

Belief and practice of Zuism is based on Sumerian poems, which Zuists recite in their worship services in honour of the gods.[24] Regular gatherings are held for such scripture recitation in honour of the gods, as well as for prayers, which are either personal or for the welfare of others. Believers conduct their daily life according to the me, which in human society are ethical codes modeled after the laws of the universe, and govern every aspect of morality from individual to social economy.[16]

Zuism is a "social religion", meaning that men and gods are considered symbiotic parts of the same complex whole. Gods govern the fate of men, and relationship with them may not be forsaken. Chiefs and priests are responsible for upkeeping the relationship with the gods through daily, monthly and yearly ordinances held at temples. Priests are called en, ensi and lugal.[16]

Annulment of debt and wealth redistribution

According to the Zuist Church, Sumer had the earliest tax system in the history of civilisation for which archeological attestations exist; it was called bala. Sumerians were aware of the threat posed to economies by the accumulation of debt, and for this reason debt was regularly annulled. This practice was called amagi (𒂼𒄄) or amargi (𒂼𒅈𒄄), literally "return to the mother", and the Zuist Church aims to restore it for today, starting with the redistribution among members of the wealth received through the tax on religious membership which governments—including that of Iceland—impose on their citizens.[25]

Charity

The members of the Zuist Church of Iceland may choose whether to devolve their paid taxes to charity.[26] In 2017, the Zuist Church devolved funds to a number of social welfare organisations: 1.1 million Icelandic crowns were donated to the Circle Children's Hospital (Barnaspítala Hringsins), 1 million to the Women's Shelter (Kvennaathvarfsins), and 300 thousand Icelandic crowns to the emergency fund of the UNICEF.[9] With the help of its members, according to the leader Ágúst Arnar Ágústsson, the Zuist Church may become "a long-term sponsor of such organisations".[26]

Temple and burial ground

On 16 January 2018, the Zuist Church of Iceland applied for the allocation of a plot of land in Reykjavík for the burial of its members.[27] On 29 May of the same year, the Zuists of Iceland presented the project and applied for the allocation of land for building a temple in the capital, which will be called the Ekur of Enlil (literally "Mount-Court of Enlil" or "Temple-Mount of Enlil"). It will function as the headquarters of the Zuist Church and as the main site for religious rituals, including baptisms and weddings. The temple will be on three levels, a ground floor and a first floor dedicated to community activities, and a shrine to the deity on the second floor. The Zuist Church opened a "fund for the ziggurat" (Zigguratsjóð) to which members will choose whether to devolve their taxes.[28]

History

1980s–2000s

Before the establishment of the Zuist Church in Iceland, there were already some Zuist or Sumerian-Mesopotamian Neopagan groups, mostly small and informal, many of which still exist, including the Temple of Sumer.[29] The Sumerian-Mesopotamian contemporary new religious movement, indeed, dates back at least to the 1980s.[5] According to the Zuist Church of Iceland, its history may be further traced back well before the 2010s to a "mother church" of Icelandic believers who dwelt in Delaware, United States.[5][30]

2010s

Zuist Church of Iceland

2013–2014: official registration and Ágúst Arnar's leadership

Zuism became a recognised religion in Iceland in 2013, when Icelandic law was amended to allow further non-Christian religions to be registered with the state.[3] The Zuist Church was founded years before, in 2010, by Ólafur Helgi Þorgrímsson,[3] who left it at an early stage of development.[31] The current head priest of the Zuist Church of Iceland is Ágúst Arnar Ágústsson,[32] who took on the office in September 2014.[26]

2015 hijacking and 2017 reinstatement of Ágúst Arnar as legitimate leader

In late 2015 the Board of Directors of the Zuist Church of Iceland was hijacked by people who were originally unrelated to the movement.[26] Under the new leader Ísak Andri Ólafsson, Zuism became a medium for a protest against the major government-supported churches and against the levying of a tax on all taxpayers, payable to their religion if they had registered one; after the protest started over 3,000 members joined in a short period of time at the end of 2015.[3] Iceland requires taxpayers to identify with one of the religions recognised by the state, or with a non-recognised religion or no religion; a tax (of about US$80, £50 in 2015) is paid to the relevant religion, if recognised, but will run directly to the government if a religion is not stated. Zuism, unlike other religions, promises to refund the money it receives from the tax.[3]

Ágúst Arnar Ágústsson and the new board led by Ísak Andri Ólafsson started a judicial dispute over the leadership of the organisation. During the process, the latter were investigated for having tried to embezzle the organisation's charges, by deceiving the State Treasury with the complicity of a government official.[26] Ágúst Arnar Ágústsson was ultimately reinstated as the leader of the movement, and, by October 2017, after two years of frozen activity, the case was closed allowing the church to dispose of its charges and refund its members.[26]

Ágúst Arnar Ágústsson stated that during the trial, fake informations were spread by the hijacking leadership and the media, so that his task from 2018 onwards would have been to "improve the image and develop the structure" of the community.[26]

Zuist Church of Britain

The Zuist Church of Britain was first established in 2013,[33] and then re-established in 2018.[34] It is headquartered in Islington, London and led by Soley Rut Magnusdottir besides Ágúst Arnar and his brother Einar.[34]

Zuist Church of Denmark

A branch of the Zuist Church was established in Denmark after the mid-2010s.[35]

Zuist Church of Germany

A branch of the Zuist Church was established in Germany after the mid-2010s.[36]

Zuist Church of Norway

A branch of Zuism was established in 2016, in Norway, as the "Congregation of Zuism in Norway", headquartered in Nittedal.[37] As of 2017 it was waiting to be registered as a recognised religion by the Norwegian government as the Zuist Church of Norway.[38]

Zuist Church of Sweden

Another branch of the Zuist Church was established in Sweden around the same time as the Norwegian branch. The Zuist Church of Sweden's headquarters are located in Malmö.[39]

Zuist Church of Switzerland

In 2015, a Swiss branch, the Zuist Church of Switzerland, was founded.[40]

Views on Christianity and Sitchinianism

According to the independent Zuist author Uligang Ansbrandt, Christianity (viewed as corrupted and dying in its modern forms) and Islam are "false religions, or non-religions", as they "fail to relink Heaven, Earth and humanity" — the word "religion" is derived from the common root of the Latin verbs religere (careful "re-reading" or "re-collecting" right practices) and religare ("re-linking"), according, respectively, to the etymologies provided by Cicero's De Rerum Natura and Lactantius' Divinae Institutiones.[41] The Zuist vision of God is presented as a thisworldly one, in which God is "the starry sky and its cycles". The God as conceived by Abrahamic religions in instead presented as a "non-existing, otherworldly abstract thing".[42] The author also rejects Sitchinianism, defined as another "abstract, nonsense science fiction", a misinterpretation of ancient knowledge which is worryingly "very popular nowadays".[42]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The name Zuism has become the most common descriptor for the modern movement of Sumerian-Mesopotamian religion, being the name under which the religion has been recognised by the Icelandic government since 2013. Other descriptors have been used, by minor informal groups which existed before the recognition under Icelandic law. These synonyms include Sumerian-Mesopotamian Neopaganism or Sumerian-Mesopotamian Reconstructionism, Babylonian Neopaganism or Babylonian Reconstructionism, and Kaldanism ("way of the Chaldeans").[2]

References

Citations

- ↑ "Populations by religious and life stance organisations". Statistics Iceland.

- ↑ Ansbrandt 2018a; Ansbrandt 2018b, zuism.it version, note i.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bromley 2018.

- ↑ "How it all began". Zuism International. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ansbrandt 2018a.

- ↑ Harriet Sherwood (8 December 2015). "Icelanders flock to religion revering Sumerian deities and tax rebates". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- ↑ "Zúistar búnir að endurgreiða sóknargjöldin". Zúistar á Íslandi. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- ↑ "Zúistar hefja endurgreiðslur á sóknargjöldum upp úr miðjum nóvember". Zúistar á Íslandi. 3 November 2017. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Zuism styrkir Kvennaathvarfið um eina milljón króna". Zúistar á Íslandi. 8 December 2017. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- ↑ Boldyreva & Grishina 2017.

- ↑ Wolfe 2015.

- ↑ "Mais pourquoi des milliers d'Islandais se convertissent au zuisme?". BFMTV. 11 December 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Didier 2009, pp. 95, Vol. I.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogers 1998, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Rogers 1998, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Kennisetningar Zuism". Zuism Iceland. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018.

- ↑ Didier 2009, pp. 261–265, Vol. III.

- 1 2 3 Rogers 1998, p. 12.

- ↑ Didier 2009, p. 265, Vol. III.

- ↑ Rogers 1998, p. 13.

- ↑ Rogers 1998, p. 11.

- ↑ Rogers 1998, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Earliest Leaders of Zuism Iceland 2010.

- ↑ "Icelanders flocking to the Zuist religion". Iceland Monitor. 1 December 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- ↑ "Amargi (Endurgreiðsla Sóknargjalda)". Zúistar á Íslandi. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Yfirlýsing frá Ágústi Arnari Ágústsssyni, forstöðumanni trúfélagsins Zuism". Zúistar á Íslandi. 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- ↑ "Fundargerð framkvæmdastjórnar KGR" (PDF). Cemeteries of Reykjavík Deanery (Kirkjugaðar Reykjavíkurprófastsdæma – KGRP). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Zuism sækir um lóð í Reykjavík". Zúistar á Íslandi. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Temple of Sumer".

- ↑ "Sagan okkar". Zuism Iceland. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018.

- ↑ "Dularfyllsta trúfélag á Íslandi verður brottfellt á næstunni". Stundin. 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- ↑ "Listi yfir skráð trúfélög og lífsskoðunarfélög". Sýslumenn.

- ↑ "Zuism Limited – Company number 08457281". Companies House, Government of the United Kingdom.

- 1 2 "Zuism Ltd – Company number 11181258". Companies House, Government of the United Kingdom.

- ↑ "Zuism Denmark".

- ↑ "Zuism Germany".

- ↑ "Congregation of Zuism in Norway". Regnskapstall for alle bedrifter i Norge.

- ↑ "Zuism Norway".

- ↑ "Where you can find us". Zuism Sweden.

- ↑ "Zuism Switzerland".

- ↑ Ansbrandt 2018b, p. 2, notes i and iii.

- 1 2 Ansbrandt 2018b, p. 2, note i.

Sources

- Boldyreva, Elena L.; Grishina, Natalia Y. (21–24 June 2017). Internet Influence on Political System Transformation in Iceland. International Conference "Internet and Modern Society" (IMS-2017). Saint Petersburg, Russia. doi:10.1145/3143699.3143710.

- Bromley, David G. (1 June 2018). "Zuism". World Religion & Spirituality Project, Virginia Commonwealth University.

- Didier, John C. (2009). "In and Outside the Square: The Sky and the Power of Belief in Ancient China and the World, c. 4500 BC – AD 200". Sino-Platonic Papers. Victor H. Mair (192). Volume I: The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot, Volume II: Representations and Identities of High Powers in Neolithic and Bronze China, Volume III: Terrestrial and Celestial Transformations in Zhou and Early-Imperial China.

- Earliest Leadership of Zuism Iceland (2010). "About Zuism". Zuist Church. Description of Zuist doctrines on the earliest version of the website of the movement.

- Rogers, J. H. (1998). "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions" (PDF). Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (1).

- Wolfe, J. N. (2015). "Zu: The Life of a Sumerian Verb in Early Mesopotamia". Academia.edu. University of California.