Vanilla

.jpg)

Vanilla is a flavoring derived from orchids of the genus Vanilla, primarily from the Mexican species, flat-leaved vanilla (V. planifolia). The word vanilla, derived from vainilla, the diminutive of the Spanish word vaina (vaina itself meaning sheath or pod), is translated simply as "little pod".[1] Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican people cultivated the vine of the vanilla orchid, called tlilxochitl by the Aztecs. Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés is credited with introducing both vanilla and chocolate to Europe in the 1520s.[2]

Pollination is required to set the vanilla fruit from which the flavoring is derived. In 1837, Belgian botanist Charles François Antoine Morren discovered this fact and pioneered a method of artificially pollinating the plant.[3] The method proved financially unworkable and was not deployed commercially.[4] In 1841, Edmond Albius, a slave who lived on the French island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean, discovered at the age of 12 that the plant could be hand-pollinated. Hand-pollination allowed global cultivation of the plant.[5]

Three major species of vanilla currently are grown globally, all of which derive from a species originally found in Mesoamerica, including parts of modern-day Mexico.[6] They are V. planifolia (syn. V. fragrans), grown on Madagascar, Réunion, and other tropical areas along the Indian Ocean; V. tahitensis, grown in the South Pacific; and V. pompona, found in the West Indies, Central America, and South America.[7] The majority of the world's vanilla is the V. planifolia species, more commonly known as Bourbon vanilla (after the former name of Réunion, Île Bourbon) or Madagascar vanilla, which is produced in Madagascar and neighboring islands in the southwestern Indian Ocean, and in Indonesia. Combined, Madagascar and Indonesia produce two-thirds of the world's supply of vanilla.

Vanilla is the second-most expensive spice after saffron[8][9] because growing the vanilla seed pods is labor-intensive.[9] Despite the expense, vanilla is highly valued for its flavor.[10] As a result, vanilla is widely used in both commercial and domestic baking, perfume manufacture, and aromatherapy.

History

According to popular belief, the Totonac people, who inhabit the east coast of Mexico in the present-day state of Veracruz, were the first to cultivate vanilla.[11] According to Totonac mythology, the tropical orchid was born when Princess Xanat, forbidden by her father from marrying a mortal, fled to the forest with her lover. The lovers were captured and beheaded. Where their blood touched the ground, the vine of the tropical orchid grew.[4] In the 15th century, Aztecs invading from the central highlands of Mexico conquered the Totonacs, and soon developed a taste for the vanilla pods. They named the fruit tlilxochitl, or "black flower", after the matured fruit, which shrivels and turns black shortly after it is picked. Subjugated by the Aztecs, the Totonacs paid tribute by sending vanilla fruit to the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan.

Until the mid-19th century, Mexico was the chief producer of vanilla.[12] In 1819, French entrepreneurs shipped vanilla fruits to the islands of Réunion and Mauritius in hopes of producing vanilla there. After Edmond Albius discovered how to pollinate the flowers quickly by hand, the pods began to thrive. Soon, the tropical orchids were sent from Réunion to the Comoros Islands, Seychelles, and Madagascar, along with instructions for pollinating them. By 1898, Madagascar, Réunion, and the Comoros Islands produced 200 metric tons of vanilla beans, about 80% of world production. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, Indonesia is currently responsible for the vast majority of the world's Bourbon vanilla production[13] and 58% of the world total vanilla fruit production.

The market price of vanilla rose dramatically in the late 1970s after a tropical cyclone ravaged key croplands. Prices remained high through the early 1980s despite the introduction of Indonesian vanilla. In the mid-1980s, the cartel that had controlled vanilla prices and distribution since its creation in 1930 disbanded.[14] Prices dropped 70% over the next few years, to nearly US$20 per kilogram; prices rose sharply again after tropical cyclone Hudah struck Madagascar in April 2000. The cyclone, political instability, and poor weather in the third year drove vanilla prices to an astonishing US$500/kg in 2004, bringing new countries into the vanilla industry. A good crop, coupled with decreased demand caused by the production of imitation vanilla, pushed the market price down to the $40/kg range in the middle of 2005. By 2010, prices were down to $20/kg. Cyclone Enawo caused in similar spike to $500/kg in 2017.[15]

Madagascar (especially the fertile Sava region) accounts for much of the global production of vanilla. Mexico, once the leading producer of natural vanilla with an annual yield of 500 tons of cured beans, produced only 10 tons in 2006. An estimated 95% of "vanilla" products are artificially flavored with vanillin derived from lignin instead of vanilla fruits.[16]

Etymology

Vanilla was completely unknown in the Old World before Cortés. Spanish explorers arriving on the Gulf Coast of Mexico in the early 16th century gave vanilla its current name. Portuguese sailors and explorers brought vanilla into Africa and Asia later that century. They called it vainilla, or "little pod". The word vanilla entered the English language in 1754, when the botanist Philip Miller wrote about the genus in his Gardener’s Dictionary.[17] Vainilla is from the diminutive of vaina, from the Latin vagina (sheath) to describe the shape of the pods.[18]

Biology

Vanilla orchid

The main species harvested for vanilla is V. planifolia. Although it is native to Mexico, it is now widely grown throughout the tropics. Indonesia and Madagascar are the world's largest producers. Additional sources include V. pompona and V. tahitiensis (grown in Niue and Tahiti), although the vanillin content of these species is much less than V. planifolia.[19]

Vanilla grows as a vine, climbing up an existing tree (also called a tutor), pole, or other support. It can be grown in a wood (on trees), in a plantation (on trees or poles), or in a "shader", in increasing orders of productivity. Its growth environment is referred to as its terroir, and includes not only the adjacent plants, but also the climate, geography, and local geology. Left alone, it will grow as high as possible on the support, with few flowers. Every year, growers fold the higher parts of the plant downward so the plant stays at heights accessible by a standing human. This also greatly stimulates flowering.

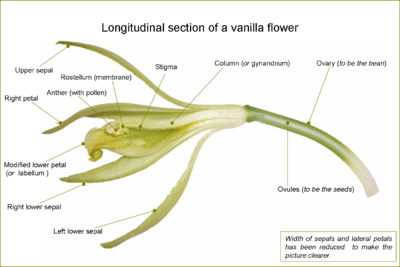

The distinctively flavored compounds are found in the fruit, which results from the pollination of the flower. These seed pods are roughly a third of an inch by six inches, and brownish red to black when ripe. Inside of these pods is an oily liquid full of tiny seeds.[20] One flower produces one fruit. V. planifolia flowers are hermaphroditic: they carry both male (anther) and female (stigma) organs. However, self-pollination is blocked by a membrane which separates those organs. The flowers can be naturally pollinated by bees of genus Melipona (abeja de monte or mountain bee), by bee genus Eulaema, or by hummingbirds.[21][22] The Melipona bee provided Mexico with a 300-year-long advantage on vanilla production from the time it was first discovered by Europeans. The first vanilla orchid to flower in Europe was in the London collection of the Honourable Charles Greville in 1806. Cuttings from that plant went to Netherlands and Paris, from which the French first transplanted the vines to their overseas colonies. The vines grew, but would not fruit outside Mexico. Growers tried to bring this bee into other growing locales, to no avail. The only way to produce fruits without the bees is artificial pollination. Today, even in Mexico, hand pollination is used extensively.

In 1836, botanist Charles François Antoine Morren was drinking coffee on a patio in Papantla (in Veracruz, Mexico) and noticed black bees flying around the vanilla flowers next to his table. He watched their actions closely as they would land and work their way under a flap inside the flower, transferring pollen in the process. Within hours, the flowers closed and several days later, Morren noticed vanilla pods beginning to form. Morren immediately began experimenting with hand pollination. A few years later in 1841, a simple and efficient artificial hand-pollination method was developed by a 12-year-old slave named Edmond Albius on Réunion, a method still used today. Using a beveled sliver of bamboo,[23] an agricultural worker lifts the membrane separating the anther and the stigma, then, using the thumb, transfers the pollinia from the anther to the stigma. The flower, self-pollinated, will then produce a fruit. The vanilla flower lasts about one day, sometimes less, so growers have to inspect their plantations every day for open flowers, a labor-intensive task.

The fruit, a seed capsule, if left on the plant, ripens and opens at the end; as it dries, the phenolic compounds crystallize, giving the fruits a diamond-dusted appearance, which the French call givre (hoarfrost). It then releases the distinctive vanilla smell. The fruit contains tiny, black seeds. In dishes prepared with whole natural vanilla, these seeds are recognizable as black specks. Both the pod and the seeds are used in cooking.

Like other orchids' seeds, vanilla seeds will not germinate without the presence of certain mycorrhizal fungi. Instead, growers reproduce the plant by cutting: they remove sections of the vine with six or more leaf nodes, a root opposite each leaf. The two lower leaves are removed, and this area is buried in loose soil at the base of a support. The remaining upper roots cling to the support, and often grow down into the soil. Growth is rapid under good conditions.

Cultivars

- Bourbon vanilla or Bourbon-Madagascar vanilla, produced from V. planifolia plants introduced from the Americas, is from Indian Ocean islands such as Madagascar, the Comoros, and Réunion, formerly named the Île Bourbon. It is also used to describe the distinctive vanilla flavor derived from V. planifolia grown successfully in tropical countries such as India.

- Mexican vanilla, made from the native V. planifolia,[24] is produced in much less quantity and marketed as the vanilla from the land of its origin. Vanilla sold in tourist markets around Mexico is sometimes not actual vanilla extract, but is mixed with an extract of the tonka bean, which contains the toxin coumarin. Tonka bean extract smells and tastes like vanilla, but coumarin has been shown to cause liver damage in lab animals and has been banned in food in the US by the Food and Drug Administration since 1954.[25]

- Tahitian vanilla is from French Polynesia, made with V. tahitiensis. Genetic analysis shows this species is possibly a cultivar from a hybrid of V. planifolia and V. odorata. The species was introduced by French Admiral François Alphonse Hamelin to French Polynesia from the Philippines, where it was introduced from Guatemala by the Manila Galleon trade.[26]

- West Indian vanilla is made from V. pompona grown in the Caribbean and Central and South America.[27]

The term French vanilla is often used to designate particular preparations with a strong vanilla aroma, containing vanilla grains and sometimes also containing eggs (especially egg yolks). The appellation originates from the French style of making vanilla ice cream with a custard base, using vanilla pods, cream, and egg yolks. Inclusion of vanilla varietals from any of the former French dependencies or overseas France may be a part of the flavoring. Alternatively, French vanilla is taken to refer to a vanilla-custard flavor.

Chemistry

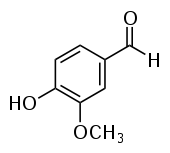

Vanilla essence occurs in two forms. Real seedpod extract is a complex mixture of several hundred different compounds, including vanillin, acetaldehyde, acetic acid, furfural, hexanoic acid, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, eugenol, methyl cinnamate, and isobutyric acid. Synthetic essence consists of a solution of synthetic vanillin in ethanol. The chemical compound vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde) is a major contributor to the characteristic flavor and aroma of real vanilla and is the main flavor component of cured vanilla beans.[28] Vanillin was first isolated from vanilla pods by Gobley in 1858.[29] By 1874, it had been obtained from glycosides of pine tree sap, temporarily causing a depression in the natural vanilla industry. Vanillin can be easily synthesized from various raw materials, but the majority of food-grade (> 99% pure) vanillin is made from guaiacol.

Cultivation

In general, quality vanilla only comes from good vines and through careful production methods. Commercial vanilla production can be performed under open field and "greenhouse" operations. The two production systems share these similarities:

- Plant height and number of years before producing the first grains

- Shade necessities

- Amount of organic matter needed

- A tree or frame to grow around (bamboo, coconut or Erythrina lanceolata)

- Labor intensity (pollination and harvest activities)[30]

Vanilla grows best in a hot, humid climate from sea level to an elevation of 1,500 m. The ideal climate has moderate rainfall, 1,500–3,000 mm, evenly distributed through 10 months of the year. Optimum temperatures for cultivation are 15–30 °C (59–86 °F) during the day and 15–20 °C (59–68 °F) during the night. Ideal humidity is around 80%, and under normal greenhouse conditions, it can be achieved by an evaporative cooler. However, since greenhouse vanilla is grown near the equator and under polymer (HDPE) netting (shading of 50%), this humidity can be achieved by the environment. Most successful vanilla growing and processing is done in the region within 10 to 20° of the equator.

Soils for vanilla cultivation should be loose, with high organic matter content and loamy texture. They must be well drained, and a slight slope helps in this condition. Soil pH has not been well documented, but some researchers have indicated an optimum soil pH around 5.3.[31] Mulch is very important for proper growth of the vine, and a considerable portion of mulch should be placed in the base of the vine.[32] Fertilization varies with soil conditions, but general recommendations are: 40 to 60 g of N, 20 to 30 g of P2O5 and 60 to 100 g of K2O should be applied to each plant per year besides organic manures, such as vermicompost, oil cakes, poultry manure, and wood ash. Foliar applications are also good for vanilla, and a solution of 1% NPK (17:17:17) can be sprayed on the plant once a month. Vanilla requires organic matter, so three or four applications of mulch a year are adequate for the plant.

Propagation, preparation and type of stock

Dissemination of vanilla can be achieved either by stem cutting or by tissue culture. For stem cutting, a progeny garden needs to be established. All plants need to grow under 50% shade, as well as the rest of the crop. Mulching the trenches with coconut husk and micro irrigation provide an ideal microclimate for vegetative growth.[33] Cuttings between 60 and 120 cm (24 and 47 in) should be selected for planting in the field or greenhouse. Cuttings below 60 to 120 cm (24 to 47 in) need to be rooted and raised in a separate nursery before planting. Planting material should always come from unflowered portions of the vine. Wilting of the cuttings before planting provides better conditions for root initiation and establishment.[30]

Before planting the cuttings, trees to support the vine must be planted at least three months before sowing the cuttings. Pits of 30 × 30 × 30 cm are dug 30 cm (12 in) away from the tree and filled with farm yard manure (vermicompost), sand and top soil mixed well. An average of 2000 cuttings can be planted per hectare (2.5 acres). One important consideration is that when planting the cuttings from the base, four leaves should be pruned and the pruned basal point must be pressed into the soil in a way such that the nodes are in close contact with the soil, and are placed at a depth of 15 to 20 cm (5.9 to 7.9 in).[32] The top portion of the cutting is tied to the tree using natural fibers such as banana or hemp.

Tissue culture

Tissue culture was first used as a means of creating vanilla plants during the 1980s at Tamil Nadu University. This was the part of the first project to grow V. planifolia in India. At that time, a shortage of vanilla planting stock was occurring in India. The approach was inspired by the work going on to tissue culture other flowering plants. Several methods have been proposed for vanilla tissue culture, but all of them begin from axillary buds of the vanilla vine.[34][35] In vitro multiplication has also been achieved through culture of callus masses, protocorns, root tips and stem nodes.[36] Description of any of these processes can be obtained from the references listed before, but all of them are successful in generation of new vanilla plants that first need to be grown up to a height of at least 30 cm (12 in) before they can be planted in the field or greenhouse.[30]

Scheduling considerations

In the tropics, the ideal time for planting vanilla is from September to November, when the weather is neither too rainy nor too dry, but this recommendation varies with growing conditions. Cuttings take one to eight weeks to establish roots, and show initial signs of growth from one of the leaf axils. A thick mulch of leaves should be provided immediately after planting as an additional source of organic matter. Three years are required for cuttings to grow enough to produce flowers and subsequent pods. As with most orchids, the blossoms grow along stems branching from the main vine. The buds, growing along the 6 to 10 in (15 to 25 cm) stems, bloom and mature in sequence, each at a different interval.[33]

Pollination

|

|

Flowering normally occurs every spring, and without pollination, the blossom wilts and falls, and no vanilla bean can grow. Each flower must be hand-pollinated within 12 hours of opening. In the wild, very few natural pollinators exist, with most pollination thought to be carried out by the shiny green Euglossa viridissima, some Eulaema spp. and other species of the euglossine or orchid bees, Euglossini, though direct evidence is lacking. Closely related Vanilla species are known to be pollinated by the euglossine bees.[37] The previously suggested pollination by stingless bees of the genus Melipona is thought to be improbable, as they are too small to be effective and have never been observed carrying Vanilla pollen or pollinating other orchids, though they do visit the flowers.[38] These pollinators do not exist outside the orchid's home range, and even within that range, vanilla orchids have only a 1% chance of successful pollination. As a result, all vanilla grown today is pollinated by hand. A small splinter of wood or a grass stem is used to lift the rostellum or move the flap upward, so the overhanging anther can be pressed against the stigma and self-pollinate the vine. Generally, one flower per raceme opens per day, so the raceme may be in flower for over 20 days. A healthy vine should produce about 50 to 100 beans per year, but growers are careful to pollinate only five or six flowers from the 20 on each raceme. The first flowers that open per vine should be pollinated, so the beans are similar in age. These agronomic practices facilitate harvest and increases bean quality. The fruits require five to six weeks to develop, but around six months to mature. Over-pollination results in diseases and inferior bean quality.[32] A vine remains productive between 12 and 14 years.

Pest and disease management

Most diseases come from the uncharacteristic growing conditions of vanilla. Therefore, conditions such as excess water, insufficient drainage, heavy mulch, overpollination, and too much shade favor disease development. Vanilla is susceptible to many fungal and viral diseases. Fusarium, Sclerotium, Phytophthora, and Colletrotrichum species cause rots of root, stem, leaf, bean, and shoot apex. These diseases can be controlled by spraying Bordeaux mixture (1%), carbendazim (0.2%) and copper oxychloride (0.2%).

Biological control of the spread of such diseases can be managed by applying to the soil Trichoderma (0.5 kg (1.1 lb) per plant in the rhizosphere) and foliar application of pseudomonads (0.2%). Mosaic virus, leaf curl, and cymbidium mosaic potex virus are the common viral diseases. These diseases are transmitted through the sap, so affected plants must be destroyed. The insect pests of vanilla include beetles and weevils that attack the flower, caterpillars, snakes, and slugs that damage the tender parts of shoot, flower buds, and immature fruit, and grasshoppers that affect cutting shoot tips.[32][33] If organic agriculture is practiced, insecticides are avoided, and mechanical measures are adopted for pest management.[30] Most of these practices are implemented under greenhouse cultivation, since such field conditions are very difficult to achieve.

Artificial vanilla

Most artificial vanilla products contain vanillin, which can be produced synthetically from lignin, a natural polymer found in wood. Most synthetic vanillin is a byproduct from the pulp used in papermaking, in which the lignin is broken down using sulfites or sulfates. However, vanillin is only one of 171 identified aromatic components of real vanilla fruits.[39]

The orchid species Leptotes bicolor is used as a natural vanilla replacement in Paraguay and southern Brazil.

Nonplant vanilla flavoring

In the United States, castoreum, the exudate from the castor sacs of mature beavers, has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a food additive,[40] often referenced simply as a "natural flavoring" in the product's list of ingredients. It is used in both food and beverages,[41] especially as vanilla and raspberry flavoring, with a total annual U.S. production of less than 300 pounds.[41][42] It is also used to flavor some cigarettes and in perfume-making, and is used by fur trappers as a scent lure.

Harvest

Harvesting vanilla fruits is as labor-intensive as pollinating the blossoms. Immature, dark green pods are not harvested. Pale yellow discoloration that commences at the distal end of the fruits is not a good indication of the maturity of pods. Each fruit ripens at its own time, requiring a daily harvest. "Current methods for determining the maturity of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews) beans are unreliable. Yellowing at the blossom end, the current index, occurs before beans accumulate maximum glucovanillin concentrations. Beans left on the vine until they turn brown have higher glucovanillin concentrations but may split and have low quality. Judging bean maturity is difficult as they reach full size soon after pollination. Glucovanillin accumulates from 20 weeks, maximum about 40 weeks after pollination. Mature green beans have 20% dry matter but less than 2% glucovanillin."[43] The accumulation of dry matter and glucovanillin are highly correlated.To ensure the finest flavor from every fruit, each individual pod must be picked by hand just as it begins to split on the end. Overmatured fruits are likely to split, causing a reduction in market value. Its commercial value is fixed based on the length and appearance of the pod.

If the fruit is more than 15 cm (5.9 in) in length, it is categorized as first-quality. The largest fruits greater than 16 cm (6.3 in) and up to as much as 21 cm (8.3 in) are usually reserved for the gourmet vanilla market, for sale to top chefs and restaurants. If the fruits are between 10 and 15 cm long, pods are under the second-quality category, and fruits less than 10 cm (3.9 in) in length are under the third-quality category. Each fruit contains thousands of tiny black vanilla seeds. Vanilla fruit yield depends on the care and management given to the hanging and fruiting vines. Any practice directed to stimulate aerial root production has a direct effect on vine productivity. A five-year-old vine can produce between 1.5 and 3 kg (3.3 and 6.6 lb) pods, and this production can increase up to 6 kg (13 lb) after a few years. The harvested green fruit can be commercialized as such or cured to get a better market price.[30][32][33]

Curing

Several methods exist in the market for curing vanilla; nevertheless, all of them consist of four basic steps: killing, sweating, slow-drying, and conditioning of the beans.[44][45]

Killing

The vegetative tissue of the vanilla pod is killed to stop the vegetative growth of the pods and disrupt the cells and tissue of the fruits, which initiates enzymatic reactions responsible for the aroma. The method of killing varies, but may be accomplished by heating in hot water, freezing, or scratching, or killing by heating in an oven or exposing the beans to direct sunlight. The different methods give different profiles of enzymatic activity.[46][47]

Testing has shown mechanical disruption of fruit tissues can cause curing processes,[48] including the degeneration of glucovanillin to vanillin, so the reasoning goes that disrupting the tissues and cells of the fruit allow enzymes and enzyme substrates to interact.[46]

Hot-water killing may consist of dipping the pods in hot water (63–65 °C (145–149 °F)) for three minutes, or at 80 °C (176 °F) for 10 seconds. In scratch killing, fruits are scratched along their length.[47] Frozen or quick-frozen fruits must be thawed again for the subsequent sweating stage. Tied in bundles and rolled in blankets, fruits may be placed in an oven at 60 °C (140 °F) for 36 to 48 hours. Exposing the fruits to sunlight until they turn brown, a method originating in Mexico, was practiced by the Aztecs.[46]

Sweating

Sweating is a hydrolytic and oxidative process. Traditionally, it consists of keeping fruits, for 7 to 10 days, densely stacked and insulated in wool or other cloth. This retains a temperature of 45–65 °C (113–149 °F) and high humidity. Daily exposure to the sun may also be used, or dipping the fruits in hot water. The fruits are brown and have attained much of the characteristic vanilla flavor and aroma by the end of this process, but still retain a 60-70% moisture content by weight.[46]

Drying

Reduction of the beans to 25–30% moisture by weight, to prevent rotting and to lock the aroma in the pods, is always achieved by some exposure of the beans to air, and usually (and traditionally) intermittent shade and sunlight. Fruits may be laid out in the sun during the mornings and returned to their boxes in the afternoons, or spread on a wooden rack in a room for three to four weeks, sometimes with periods of sun exposure. Drying is the most problematic of the curing stages; unevenness in the drying process can lead to the loss of vanillin content of some fruits by the time the others are cured.[46]

Conditioning

Conditioning is performed by storing the pods for five to six months in closed boxes, where the fragrance develops. The processed fruits are sorted, graded, bundled, and wrapped in paraffin paper and preserved for the development of desired bean qualities, especially flavor and aroma. The cured vanilla fruits contain an average of 2.5% vanillin.

Grading

Once fully cured, the vanilla fruits are sorted by quality and graded. Several vanilla fruit grading systems are in use. Each country which produces vanilla has its own grading system,[49] and individual vendors, in turn, sometimes use their own criteria for describing the quality of the fruits they offer for sale.[50] In general, vanilla fruit grade is based on the length, appearance (color, sheen, presence of any splits, presence of blemishes), and moisture content of the fruit.[49][51] Whole, dark, plump and oily pods that are visually attractive, with no blemishes, and that have a higher moisture content are graded most highly.[52] Such pods are particularly prized by chefs for their appearance and can be featured in gourmet dishes.[50] Beans that show localized signs of disease or other physical defects are cut to remove the blemishes; the shorter fragments left are called "cuts" and are assigned lower grades, as are fruits with lower moisture contents.[51] Lower-grade fruits tend to be favored for uses in which the appearance is not as important, such as in the production of vanilla flavoring extract and in the fragrance industry.

Higher-grade fruits command higher prices in the market.[49][51] However, because grade is so dependent on visual appearance and moisture content, fruits with the highest grade do not necessarily contain the highest concentration of characteristic flavor molecules such as vanillin,[53] and are not necessarily the most flavorful.[50]

| Grade | Color | Appearance / feel | Approximate moisture content† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black | dark brown to black | supple with oily luster | > 30% |

| TK (Brown, or Semi-Black) | dark brown to black sometimes with a few red streaks | like Black but dryer/stiffer | 25–30% |

| Red Fox (European quality) | brown with reddish variegation | a few blemishes | 25% |

| Red American quality | brown with reddish variegation | similar to European red but more blemishes and dryer/stiffer | 22–25% |

| Cuts | short, cut, and often split fruits, typically with substandard aroma and color |

† moisture content varies among sources cited

A simplified, alternative grading system has been proposed for classifying vanilla fruits suitable for use in cooking:[50]

| Grade A / Grade I | 15 cm and longer, 100–120 fruits per pound | Also called "Gourmet" or "Prime". 30–35% moisture content. |

| Grade B / Grade II | 10–15 cm, 140–160 fruits per pound | Also called "Extract fruits". 15–25% moisture content. |

| Grade C / Grade III | 10 cm |

Under this scheme, vanilla extract is normally made from Grade B fruits.[50]

Production

| Country | Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|

In 2016, world production of vanilla was 7,940 tonnes, led by Madagascar with 37% of the total, and Indonesia with 29% (table). Due to drought, cyclones, and poor farming practices in Madagascar, there are concerns about the global supply and costs of vanilla in 2017 and 2018.[59] Such is the intensity of criminal enterprises that some Madagascar farmers patrol their fields armed with machetes. [60][61]

Uses

Culinary uses

The four main commercial preparations of natural vanilla are:

- Whole pod

- Powder (ground pods, kept pure or blended with sugar, starch, or other ingredients)[62]

- Extract (in alcoholic or occasionally glycerol solution; both pure and imitation forms of vanilla contain at least 35% alcohol)[63]

- Vanilla sugar, a packaged mix of sugar and vanilla extract

Vanilla flavoring in food may be achieved by adding vanilla extract or by cooking vanilla pods in the liquid preparation. A stronger aroma may be attained if the pods are split in two, exposing more of a pod's surface area to the liquid. In this case, the pods' seeds are mixed into the preparation. Natural vanilla gives a brown or yellow color to preparations, depending on the concentration. Good-quality vanilla has a strong, aromatic flavor, but food with small amounts of low-quality vanilla or artificial vanilla-like flavorings are far more common, since true vanilla is much more expensive.

Regarded as the world's most popular aroma and flavor,[64] vanilla is a widely used aroma and flavor compound for foods, beverages and cosmetics, as indicated by its popularity as an ice cream flavor.[65] Although vanilla is a prized flavoring agent on its own, it is also used to enhance the flavor of other substances, to which its own flavor is often complementary, such as chocolate, custard, caramel, coffee, and others. Vanilla is a common ingredient in Western sweet baked goods, such as cookies and cakes.

The food industry uses methyl and ethyl vanillin as less-expensive substitutes for real vanilla. Ethyl vanillin is more expensive, but has a stronger note. Cook's Illustrated ran several taste tests pitting vanilla against vanillin in baked goods and other applications, and to the consternation of the magazine editors, tasters could not differentiate the flavor of vanillin from vanilla;[66] however, for the case of vanilla ice cream, natural vanilla won out.[67] A more recent and thorough test by the same group produced a more interesting variety of results; namely, high-quality artificial vanilla flavoring is best for cookies, while high-quality real vanilla is slightly better for cakes and significantly better for unheated or lightly heated foods.[68] The liquid extracted from vanilla pods was once believed to have medical properties, helping with various stomach ailments.[69]

Contact dermatitis

When propagating vanilla orchids from cuttings or harvesting ripe vanilla beans, care must be taken to avoid contact with the sap from the plant's stems. The sap of most species of Vanilla orchid which exudes from cut stems or where beans are harvested can cause moderate to severe dermatitis if it comes in contact with bare skin. Washing the affected area with warm soapy water will effectively remove the sap in cases of accidental contact with the skin. The sap of vanilla orchids contains calcium oxalate crystals, which appear to be the main causative agent of contact dermatitis in vanilla plantation workers.[70][71]

Gallery

A vanilla planting in an open field on Réunion

A vanilla planting in an open field on Réunion A vanilla planting in a "shader" (ombrière) on Réunion

A vanilla planting in a "shader" (ombrière) on Réunion Flower

Flower Green fruits

Green fruits

References

- ↑ Ackerman, James D. (2002). "Vanilla". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee. Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 26. New York and Oxford. Archived from the original on 29 February 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

Spanish vainilla, little pod or capsule, referring to long, podlike fruits

- ↑ The Herb Society of Nashville. "The Life of Spice". The Herb Society of Nashville. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011.

Following Montezuma’s capture, one of Cortés' officers saw him drinking "chocolatl" (made of powdered cocoa beans and ground corn flavored with ground vanilla pods and honey). The Spanish tried this drink themselves and were so impressed by this new taste sensation that they took samples back to Spain.' and 'Actually it was vanilla rather than the chocolate that made a bigger hit and by 1700 the use of vanilla was spread over all of Europe. Mexico became the leading producer of vanilla for three centuries. – Excerpted from 'Spices of the World Cookbook' by McCormick and 'The Book of Spices' by Frederic Rosengarten, Jr

- ↑ Morren, C. (1837) "Note sur la première fructification du Vanillier en Europe" (Note on the first fruiting of vanilla in Europe), Annales de la Société Royale d'Horticulture de Paris, 20 : 331–334. Morren describes the process of artificially pollinating vanilla on p. 333: "En effet, aucun fruit n'a été produit que sur les cinquante-quatre fleurs auxquelles j'avais artificiellement communiqué le pollen. On enlève le tablier ou on le soulève, et on met en contact avec le stigmate une mass pollinique entière, ou seulement une partie de cette masse, car une seule de celles-ci, coupée en huit ou dix pièces, peut féconder autant de fleurs." (In effect, fruit has been produced only on fifty-four flowers to which I artificially communicated pollen. One removes the labellum or one raises it, and one places in contact with the stigma a complete mass of pollen [i.e., pollinium], or just a part of that mass, for just one of these, cut into eight or ten pieces, can fertilize as many flowers.) Available on-line at: Hortalia.org

- 1 2 Janet Hazen (1995). Vanilla. Chronicle Books.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Silver Cloud Estates. "History of Vanilla". Silver Cloud Estates. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

In 1837 the Belgian botanist Morren succeeded in artificially pollinating the vanilla flower. On Reunion, Morren's process was attempted, but failed. It was not until 1841 that a 12-year-old slave by the name of Edmond Albius discovered the correct technique of hand-pollinating the flowers.

- ↑ Lubinsky, Pesach; Bory, Séverine; Hernández Hernández, Juan; Kim, Seung-Chul; Gómez-Pompa, Arturo (2008). "Origins and Dispersal of Cultivated Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. [Orchidaceae])". Economic Botany. 62 (2): 127–38. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9014-y.

- ↑ Besse, Pascale; Silva, Denis Da; Bory, Séverine; Grisoni, Michel; Le Bellec, Fabrice; Duval, Marie-France (2004). "RAPD genetic diversity in cultivated vanilla: Vanilla planifolia, and relationships with V. Tahitensis and V. Pompona". Plant Science. 167 (2): 379–85. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.04.007.

- ↑ Le Cordon Bleu (2009). Le Cordon Bleu Cuisine Foundations. Cengage learning. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-4354-8137-4.

- 1 2 Parthasarathy, V. A.; Chempakam, Bhageerathy; Zachariah, T. John (2008). Chemistry of Spices. CABI. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-84593-405-7.

- ↑ Rosengarten, Frederic (1973). The Book of Spices. Pyramid Books. ISBN 978-0-515-03220-8.

- ↑ Rain, Patricia; Lubinsky, Pesach (2011). "Vanilla Use in Colonial Mexico and Traditional Totonac Vanilla Farming". In Odoux, Eric; Grisoni, Michel. Vanilla. USA: CRC Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-4200-8337-8.

- ↑ Rain, Patricia; Lubinsky, Pesach (2011). "Vanilla Production in Mexico". In Odoux, Eric; Grisoni, Michel. Vanilla. USA: CRC Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-1-4200-8337-8.

- ↑ "FAO's Statistical Database - FAOSTAT". 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Bleu, The Chefs of Le Cordon (21 April 2010). "Le Cordon Bleu Cuisine Foundations". Cengage Learning. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Forani, Jonathan (20 September 2017). "Eager bakers may face a cake crisis as vanilla supply evaporates". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ↑ "Rainforest Vanilla Conservation Association". RVCA. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ↑ Correll D (1953) Vanilla: its botany, history, cultivation and economic importance. Econ Bo 7(4): 291–358.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ "Brockman, Terra Types of Vanilla June 11, 2008 Chicago Tribune". Chicagotribune.com. 11 June 2008. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ Diderot, Denis. "Vanilla". The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert: Collaborative Translations Project. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Vanilla orchid (#7) - Vanilla planifolia". Pollinator Partnership. 2014. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ "Vanilla planifolia: Life History & Reproduction". Bioweb: University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Flower with money power". The Hindu. 10 May 2004. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ Mushet, Cindy; Table, Sur La (21 October 2008). The Art and Soul of Baking. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 9780740773341. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017.

- ↑ "IMPORT ALERT IA2807: "DETENTION WITHOUT PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF COUMARIN IN VANILLA PRODUCTS (EXTRACTS – FLAVORINGS – IMITATIONS)"". U.S. Food and Drug Administration Office of Regulatory Affairs. January 1998. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ "Tahitian Vanilla Originated in Maya Forests, Says UC Riverside Botanist". University of California at Riverside, Newsroom. 21 August 2008. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ "Vanilla pompona". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ↑ Bomgardner, M.M. (2016). "The problem with vanilla". Chemical and Engineering News. 94: 38–42. doi:10.1021/cen-09436-cover. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Gobley, N.-T. (1858). "Recherches sur le principe odorant de la vanilla" [Research on the fragrant substance of vanilla]. Journal de Pharmacie et de Chimie, Series 3. 34: 401–405. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anilkumar, A. S. (February 2004). "Vanilla cultivation: A profitable agri-based enterprise" (PDF). Kerala Calling: 26–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Berninger, F., Salas, E., 2003. "Biomass dynamics of Erythrina lanceolata as influenced by shoot-pruning intensity in Costa Rica." Agro-forestry Systems, 57:19–28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Davis, Elmo W. (1983). "Experiences with growing vanilla (Vanilla planifolia)". Acta Horticulturae. 132: 23–9. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Elizabeth, K. G. (2002). "Vanilla: an orchid spice". Indian Journal of Arecanut Spices and Medicinal Plants. 4 (2): 96–8.

- ↑ George, P. S.; Ravishankar, G. A. (1997). "In vitro multiplication of Vanilla planifolia using axillary bud explants". Plant Cell Reports. 16 (7): 490–494. doi:10.1007/BF01092772.

- ↑ Kononowicz, H.; Janick, J. (1984). "In vitro propagation of Vanilla planifolia". HortScience. 19 (1): 58–9.

- ↑ Giridhar P, Ravishankar GA (2004). "Efficient micropropagation of Vanilla planifolia Andr. under influence of thidiazuron, zeatin and coconut milk". Indian Journal of Biotechnology. 3 (1): 113–118. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014.

- ↑ Gigant, Rodolphe; Bory, Séverine; Grisoni, Michel; Besse, Pascal (2011). Grillo, Oscar; Venora, Gianfranco, eds. The Dynamical Processes of Biodiversity - Case Studies of Evolution and Spatial Distribution. Croatia: InTech. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-953-307-772-7. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ Lubinsky, Pesach; Van Dam, Matthew; Van Dam, Alex (2006). "Pollination of Vanilla and Evolution in the Orchidaceae" (PDF). Lindleyana. 75 (12): 926–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ "About Vanilla – Vanilla imitations". Cook Flavoring Company. 2011. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ↑ Burdock GA (2007). "Safety assessment of castoreum extract as a food ingredient". Int. J. Toxicol. 26 (1): 51–55. doi:10.1080/10915810601120145. PMID 17365147.

- 1 2 Kennedy, C Rose (2015). "What's in a flavor? Vanillin dreams". The Flavor Rundown: Natural vs. Artificial Flavors. Boston, MA: Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Burdock, George A., Fenaroli's Handbook of Flavor Ingredients Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. CRC Press, 2005. p. 277.

- ↑ S. Van Dyka, P. Holforda, P. Subedib, K. Walshb, M. Williamsa, W.B. McGlassona (2014). "Determining the harvest maturity of vanilla beans". Scientia Horticulturae. 168: 249–257. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2014.02.002.

- ↑ Havkin-Frenkel D, French JC, Graft NM (2004). "Interrelation of curing and botany in vanilla (vanilla planifolia) bean". Acta Horticulturae. 629: 93–102. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014.

- ↑ Havkin-Frenkel, D.; French, J. C.; Pak, F. E.; Frenkel, C. (2003). "Botany and curing of vanilla". Journal of Aromatic medicinal plants.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Frenkel, Chaim; Ranadive, Arvind S.; Vázquez, Javier Tochihuitl; Havkin-Frenkel, Daphna (2010). "Curing of Vanilla". In Havkin-Frenkel, Daphna; Belanger, Faith. Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 79–106 [87]. ISBN 978-1-4443-2937-7. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016.

- 1 2 Arana, Francisca E. (October 1944). "Vanilla curing and its chemistry". Bulletin. Federal Experiment Station of the United States Department of Agriculture in Mayaguez, Puerto Rico (42): 1–17. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Methods of dehydrating and curing vanilla fruit US Patent 2,621,127

- 1 2 3 4 Havkin-Frenkel, Daphna; Belanger, Faith C. (2011). Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 142–145. ISBN 978-1-4051-9325-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Vanilla". Vanilla Review. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Nielsen, Jr., Chat (1985). The Story of Vanilla. Chicago: Nielsen-Massey Vanillas.

- ↑ "Vanilla". Spices Board of India. Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ K. Gassenheimer; E. Binggeli (2008). Imre Blank; Matthias Wüst; Chahan Yeretzian, eds. "Vanilla Bean Quality - A Flavour Industry View" in Expression of Multidisciplinary Flavour Science: Proceedings of the 12th Weurman Symposium (Interlaken, Switzerland 2008). Wädensil, Switzerland: Zürich University of Applied Sciences. pp. 203–206. ISBN 978-3-905745-19-1.

- ↑ "LFIE Vanilla Products". Lopat Frederic Import Export. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "Vanilla Bourbon". SA. VA. Import - Export. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "Vanilla Products". Gascar Trading Company. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "Vanilla Bean Products". Vanexco. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "Vanilla production in 2016; Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity from pick lists". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ "Transforming the vanilla supply chain in Madagascar". Medium. 17 September 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ Kacungira, Nancy (2018-08-19). "Fighting the Vanilla Thieves of Madagascar". BBC. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- ↑ O’Reilly, Finbarr (29 Aug 2018). "Precious as Silver, Vanilla Brings Cash and Crime to Madagascar". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires at least 12.5% of pure vanilla (ground pods or oleoresin) in the mixture Archived 29 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires at least 35% vol. of alcohol and 13.35 ounces of pod per gallon Archived 1 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Rain, Patricia (2004). Vanilla: The Cultural History of the World's Most Popular Flavor and Fragrance. Tarcher. ISBN 9781585423637.

- ↑ "Vanilla remains top ice cream flavor with Americans". International Dairy Foods Association, Washington, DC. 23 July 2013. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ "Pure versus Imitation Vanilla Extract". Cooks Illustrated. 1 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ "Tasting lab: Vanilla Ice Cream". Cooks Illustrated. 1 May 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ "Vanilla Extract". 1 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ↑ Jaucourt, Louis (1765). "Vanilla". Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ "Vanilla planifolia Andrews - Plants of the World Online - Kew Science". powo.science.kew.org. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "Vanilla". Plants for a Future. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017.

Further reading

- Ecott, Tim (2004). Vanilla: Travels in Search of the Luscious Substance. London: Penguin, New York: Grove Atlantic

- Rain, Patricia (2004). Vanilla: The Cultural History of the World's Favorite Flavor and Fragrance. New York: J. P. Tarcher/Penguin.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vanilla. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Vanilla |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

| Look up vanilla in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Kew Species Profile: Vanilla planifolia (vanilla)

- History, Classification and Lifecycle of Vanilla planifolia

- Spices at UCLA History & Special Collections

- Vanilla and Extracts at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- "The Present State of the West-Indies: Containing an Accurate Description of What Parts Are Possessed by the Several Powers in Europe" by Thomas Kitchin, 1778, in which Kitchin discusses vanilla