Shiso

| Shiso | |

|---|---|

| Red shiso | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Lamiaceae |

| Genus: | Perilla |

| Species: | P. frutescens |

| Variety: | P. f. var. crispa |

| Trinomial name | |

| Perilla frutescens var. crispa (Thunb.) H.Deane | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Perilla frutescens var. crispa, also called shiso (/ˈʃiːsoʊ/,[2] from Japanese シソ) is a variety of species Perilla frutescens of the genus Perilla, belonging to the mint family, Lamiaceae. Shiso is a perennial plant that may be cultivated as an annual in temperate climates. The plant occurs in red (purple-leaved) and green-leaved forms. There are also frilly ruffled-leaved forms, called chirimen-jiso, and forms that are red only on the bottom side, called katamen-jiso.

Names

This herb has also been known in English as the "beefsteak plant", possibly on account of the purple-leaved varieties evoking the bloody-red color of meat.[3] It is sometimes referred to by its genus name, perilla, but this is ambiguous as it could also refer to a different cultigen (Perilla frutescens var. frutescens) which is distinguished as egoma in Japan and tul-kkae or "wild sesame" in Korea.[4][5] The perilla or "beefsteak plant" began to be recognized by the native Japanese name shiso among American diners of Japanese cuisine, especially afficionados of sushi in the later decades of the 20th century.[6]

In Japan, the cultigen is called shiso (紫蘇/シソ; [ɕiso̞]).[7][8] In Vietnam, it is called tía tô ([tiɜ˧ˀ˦ to˧˧]).[9] The Japanese name shiso and the Vietnamese tía tô are cognates, each loan words from zǐsū (紫苏/紫蘇),[10] which means Perilla frutescens in Chinese. (Perilla frutescens var. crispa is called huíhuísū (回回苏/回回蘇) in Chinese.) The first character 紫[11] means "purple",[7] and the second 蘇[12] means "to be resurrected, revived, rehabilitated". In Japan, shiso traditionally denoted the purple-red form.[13] In recent years, green is considered typical, and red considered atypical.

The red-leaved form of shiso was introduced into the West around the 1850s,[14] when the ornamental variety was usually referred to as P. nankinensis. This red-leafed border plant eventually earned the English-language name "beefsteak plant".[3]

Other common names include "perilla mint",[15] "Chinese basil",[16][17][18] and "wild basil".[16] The alias "wild coleus"[19] or "summer coleus"[16] probably describe ornamental varieties. The red shiso or su tzu types are called purple mint[16] or purple mint plant.[15] It is called rattlesnake weed[16] in the Ozarks, because the sound the dried stalks make when disturbed along a footpath is similar to a rattlesnake's rattling sound.[20]

Origins and distribution

Suggested native origins are mountainous terrains of India and China,[21] although some books say Southeast Asia.[22]

Shiso spread throughout ancient China. One of the early mentions on record occurs in Renown Physician's Extra Records (Chinese: 名醫別錄; pinyin: Míng Yī Bié Lù), around 500 AD,[23] where it is listed as su (蘇), and some of its uses are described.

The perilla was introduced into Japan around the eighth to ninth centuries.[24]

The species was introduced into the Western horticulture as an ornamental and became widely naturalized and established in the United States and may be considered weedy or invasive.

Description

Though now lumped into a single species of polytypic character, the two cultigens continue to be regarded as distinct commodities in the Asian countries where they are most exploited. While they are morphologically similar, the modern strains are readily distinguishable. Accordingly, the description is used separately or comparatively for the cultivars.

Shiso grows to 40–100 centimetres (16–39 in) tall.[25] It has broad ovate leaves with pointy ends and serrated margins, arranged oppositely with long leafstalks. Shiso's distinctive flavor comes from its perillaldehyde component,[26] which present only in low concentration in other perilla varieties.

The red (purple) forms of the shiso (forma purpurea and crispa) come from its pigment, called "perilla anthocyanin" or shisonin[27] The color is present in both sides of the leaves, the entire stalk, and flower buds (calyces).

The red crinkly-leafed version (called chirimenjiso in Japan) was the form of shiso first examined by Western botany, and Carl Peter Thunberg named it P. crispa (the name meaning "wavy or curly"). That Latin name was later retained when the shiso was reclassed as a variety.

Bicolored cultivars (var. Crispa forma discolor Makino; カタメンジソ (katamenjiso) or katamen shiso) are red on the underside of the leaf.[28][29] Green crinkly-leafed cultivars (called chirimenaojiso, forma viridi-crispa) are seen.

Shiso produces harder, smaller seeds compared to other perilla varieties.[30][31] Shiso seeds weigh about 1.5 g per 1000 seeds.[32]

Red shiso

The purple-red type may be known as akajiso (赤ジソ/紅ジソ "red shiso"). It is often used for coloring umeboshi (English: pickled plum). The shiso leaf turns bright red when it reacts with the umezu, the vinegary brine that wells up from the plums after being pickled in their vats.[7][33] The red pigment is identified as the Perilla anthocyanin, a.k.a. shisonin.[34] The mature red leaves make undesirable raw salad leaves, but germinated sprouts, or me-jiso (芽ジソ), have been long used as garnish to accent a Japanese dish, such as a plate of sashimi.[7][35] The tiny pellets of flower-buds (ho-jiso) and seed pods (fruits) can be scraped off using the chopstick or fingers and mixed into the soy sauce dip to add the distinct spicy flavor, especially to flavor fish.[35][36]

Green shiso

Bunches of green shiso-leaves packaged in styrofoam trays can be found on supermarket shelves in Japan and Japanese food markets in the West. Earnest production of the leafy herb did not begin until the 1960s.Shimbo (2001), p. 58

One anecdote is that c. 1961, a cooperative or guild of tsuma (ツマ "garnish") commodities based in Shizuoka Prefecture picked large-sized green leaves of shiso and shipped them to the Osaka market. They gained popularity such that ōba (大葉 "big leaf") became the trade name for bunches of picked green leaves.[37]

A dissenting account places its origin in the city of Toyohashi, Aichi, the foremost ōba-producer in the country,[38] and claims Toyohashi's Greenhouse Horticultural Agricultural Cooperative[lower-alpha 1] experimented with planting c. 1955, and around 1962 started merchandizing the leaf part as Ōba. In 1963 they organized "cooperative sorting and sales" of the crop (kyōsen kyōhan (共選・共販), analogous to cranberry cooperatives in the US) and c. 1970 they achieved year-round production.[39]

The word ōba was originally a trade name and was not entered into the Shin Meikai kokugo jiten until its 5th edition (Kindaichi (1997)) and is absent from the 4th edition (1989). This dictionary is more progressive than the Kojien cited previously, as Kindaichi's dictionary, from the 1st ed. (1972), and definitely in the 2nd ed. (1974) defined shiso as a plant with leaves of "purple(green) color".[40]

Chemical composition

Shiso contain only about 25.2–25.7% lipid,[41] but still contains a comparable 60% ratio of ALA.[42][43]

The plant produces the natural product perilloxin, which is built around a 3-benzoxepin moiety. Perilloxin inhibits the enzyme cyclooxygenase with an IC50 of 23.2 μM.[44] Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like aspirin and ibuprofen also work by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase enzyme family.

Of the known chemotypes of perilla, PA (main component: perillaldehyde) is the only one used for culinary purposes. Other chemotypes are PK (perilla ketone), EK (eschscholzia ketone), PL (perillene), PP (phenylpropanoids: myristicin, dillapiole, elemicin), C (citral) and a type rich in rosefuran.

Perilla ketone is toxic to some animals. When cattle and horses consume purple mint (of the PK chemotype) while grazing in fields in which it grows, the perilla ketone causes pulmonary edema, leading to a condition sometimes called perilla mint toxicosis.

The oxime of perillaldehyde (perillartin) is used as an artificial sweetener in Japan, as it is about 2,000 times sweeter than sucrose.

The pronounced flavor and aroma of shiso derives from perillaldehyde,[45] but this substance is lacking in the "wild sesame" and "sesame leaf" variety. Other aromatic essential oils present are limonene,[45] caryophyllene,[45] and farnesene.

Many forms are rich in perilla ketone, which is a potent lung toxin to some livestock,[46] though effects on humans remains to be studied.[46]

The artificial sweetener perillartine can be synthesized from perillaldehyde, but it is used in Japan only for sweetening tobacco,[47] despite being 2000 times sweeter than sucrose, owing to its bitterness and aftertaste, and insolubility in water.[48]

Cultivation

In temperate climates, the plant is self-sowing, but the seeds are not viable after long storage, and germination rates are low after a year.

The weedy types have often lost the characteristic shiso fragrance and are not suited for eating (cf. perilla ketone). Also, the red leaves are not ordinarily served raw.

Culinary use

Japan

Called shiso (紫蘇) in Japanese, P. frutescens var. crispa leaves, seeds, and sprouts are used extensively in Japanese cuisine. Green leaves, called aojiso (青紫蘇; "blue shiso"), are used as a herb in cold noodle dishes (hiyamugi and sōmen), cold tofu (hiyayakko), tataki and namerō. Aojiso is also served fresh with sashimi. Purple leaves, called akajiso (赤紫蘇; "red shiso"), are used to dye pickled plums (umeboshi). Shiso seed pods are salted and preserved to be used as a spice, while the germinated sprouts called mejiso (芽紫蘇) are used as garnish. The inflorescence of shiso, called hojiso (穂紫蘇), is used as garnish on a sashimi plate.

The Japanese name for the variety of perilla normally used in Japanese cuisine (Perilla frutescens var. crispa) is shiso (紫蘇). This name is already commonplace in US mass media's coverage of Japanese restaurants and cuisine. The Japanese call the green type aojiso (青紫蘇), or ooba ("big leaf"), and often eat the fresh leaves with sashimi (sliced raw fish) or cut them into thin strips in salads, spaghetti, and meat and fish dishes. It is also used as a savory herb in a variety of dishes, even as a pizza topping (initially it was used in place of basil). In the summer of 2009, Pepsi Japan released a seasonal flavored beverage, Pepsi Shiso.[49]

The Japanese shiso leaves grow in green, red, and bicolored forms, and crinkly (chirimen-jiso) varieties, as noted. Parts of the plants eaten are the leaves, flower and buds from the flower stalks, fruits and seeds, and sprouts.

The purple form is called akajiso (赤紫蘇, red shiso), and is used to dye umeboshi (pickled ume) red or combined with ume paste in sushi to make umeshiso maki. It can also be used to make a sweet, red juice to enjoy during summer.

Japanese use green shiso leaves raw with sashimi. Dried leaves are also infused to make tea. The red shiso leaf is not normally consumed fresh, but needs to be e.g. cured in salt. The pigment in the leaves turns from purple to bright red color when steeped in umezu, and is used to color and flavor umeboshi.

An inflorescence of shiso, called hojiso (ear shiso), is typically used as garnish on a sashimi plate; the individual flowers can be stripped off the stem using the chopstick, adding its flavor to the soy sauce dip. The fruits of the shiso (shiso-no-mi), containing fine seeds (mericarp) about 1 mm or less in diameter (about the size of mustard seed), can be preserved in salt and used as a spice or condiment. Young leaves and flower buds are used for pickling in Japan and Taiwan.

The other type of edible perilla (Perilla frutescens) called egoma (荏胡麻) is of limited culinary importance in Japan, though this is the variety commonly used in nearby Korea. The cultivar is known regionally as jūnen in the Tohoku (northeast) regions of Japan. The term means "ten years", supposedly because it adds this many years to one's lifespan. A preparation called shingorō, made in Fukushima prefecture, consists of half-pounded unsweet rice patties which are skewered, smeared with miso, blended with roasted and ground jūnen seeds, and roasted over charcoal. The oil pressed from this plant was once used to fuel lamps in the Middle Ages. The warlord Saitō Dōsan, who started out in various occupations, was a peddler of this type of oil, rather than the more familiar rapeseed oil, according to a story by historical novelist Ryōtarō Shiba.

A whole leaf of green shiso is often used as a receptacle to hold wasabi, or various tsuma (garnishes) and ken (daikon radishes, etc., sliced into fine threads). It seems to have superseded baran, the serrated green plastic film, named after the Aspidistra plant, once used in takeout sushi boxes.

- Green leaves

The green leaf can be chopped and used as herb or condiment for an assortment of cold dishes such as:

Chopped leaves can be used to flavor any number of fillings or batter to be cooked, for use in warm dishes. A whole leaf battered on the obverse side is made into tempura.[50] Whole leaves are often combined with shrimp or other fried items.

- Red leaves

Red leaves are used for making pickled plum (umeboshi) as mentioned, but this is no longer a yearly chore undertaken by the average household. Red shiso is used to color shiba-zuke, a type of pickled eggplant served in Kyoto. (Cucumber, myoga, and shiso seeds may also be used),[51] Kyoto specialty.

- Seeds

The seed pods or berries of the shiso may be salted and preserved like a spice.[52] They can be combined with fine slivers of daikon to make a simple salad.

One source from the 1960s says that oil expressed from shiso seeds was once used for deep-frying purposes.[7]

- Sprouts

The germinated sprouts (cotyledons)[53] used as garnish are known as mejiso (芽ジソ). Another reference refers to the me-jiso as the moyashi (sprout) of the shiso.[7]

Any time it is mentioned that shiso "buds" are used, there is reason to suspect this is a mistranslation for "sprouts" since the word me (芽) can mean either.[54][lower-alpha 2]

Though young buds or shoots are not usually used in restaurants, the me-jiso used could be microgreen size.[55] People engaged in growing their own shiso in planters refer to the plucked seedlings they have thinned as mejiso.[56]

- Yukari

The name yukari refers to dried and pulverized red-shiso flakes,[57] and has become as a generic term,[58] although Mishima Foods Co. insists it is the proprietary name for its products.[59] The term yukari-no-iro has signified the color purple since the Heian period, based on a poem in the Kokin Wakashū (c. 910) about a murasaki or gromwell blooming in Musashino (an old name for the Tokyo area).[60] Moreover, the term Murasaki-no-yukari has been used as an alias for Lady Murasaki's romance of the shining prince.

- Furikake

Other than the yukari variety, there are many commercial brand furikake-type sprinkle-seasoning products that contain shiso. They can be sprinkled on rice or mixed into musubi. They are often sprinkled on pasta.

Shiso pasta can be made from fresh-chopped leaves, sometimes combined with the crumbled roe of tarako.[61] Rather than cooking the cod roe, the hot pasta is tossed into it.

Korea

P. frutescens var. crispa, called soyeop (소엽), is a less-popular culinary plant than P. frutescens in Korea. It is, however, a commonly seen wild plant, and the leaves are occasionally used as a ssam vegetable and a bibimbap ingredient.[62] The purplish leaves are sometimes pickled in soy sauce or soybean paste as a jangajji, or deep-fried with a thin coat of rice-flour batter.[62]

Laos

The purple leaves, called pak maengda (ຜັກແມງດາ), are strong in fragrance, but not ruffled. They are used for Lao rice vermicelli, khao poon (ເຂົ້າປຸ້ນ), which is very similar to the Vietnamese bún. They are used as part of the dish for their fragrance.

Vietnam

Tía tô is a cultivated P. frutescens var. crispa in Vietnam,[63] which compared to the Japanese shiso has slightly smaller leaves but much-stronger aromatic flavor. It is native to Southeast Asia.[64][65] Unlike the Perilla frutescens counterpart, the leaves on the Vietnamese perilla have green color on the top side and purplish-red on the bottom side.

In North and South Vietnam, the Vietnamese perilla are eaten raw or used in Vietnamese salads, soups, or stir-fried dishes. The strong flavors are perfect for cooking seafoods such as shrimp and fish dishes. Aromatic leaves are also widely used in pickling. Plants can be grown in open fields, gardens, or containers.

Vietnamese cuisine uses a P. frutescens var. crispa variety similar to the Japanese perilla, but with greenish bronze on the top face and purple on the opposite face. The leaves are smaller and have a much stronger fragrance. In Vietnamese, it is called tía tô, derived from the characters (紫蘇) whose standard pronunciation in Vietnamese is tử tô. It is usually eaten as a garnish in rice vermicelli dishes called bún and a number of stews and simmered dishes.

Ornamental use

The red-leaved shiso, in earlier literature referred to as Perilla nankinensis, became available to gardening enthusiasts in England circa 1855.[14] By 1862, the English were reporting overuse of this plant, and proposing Coleus vershaeffeltii [66] or Amaranthus melancholicus var. ruber made available by J.G. Veitch [67] as an alternative.

It was introduced later in the United States, perhaps in the 1860s.[68][69]

Nutritional

Bactericidal and preservative effects of the shiso, due to the presence of terpenes such as perilla alcohol, have been noted.[50]

Statistical data

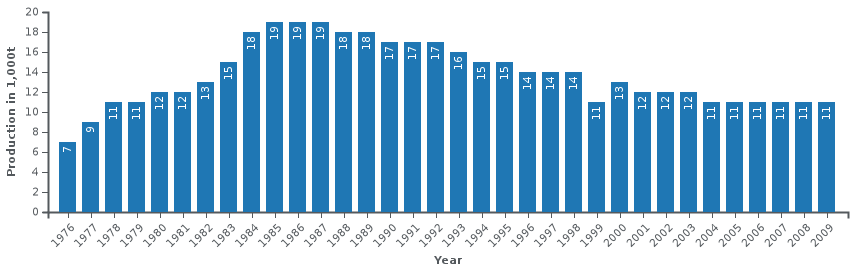

The bar graph shows the trend in total production of shiso in Japan. (Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries statistics. For green shiso, cumulative figures for shiso as vegetable is used.)[39][70]

Raw data starts from 1960, but for the shiso, the production figure was either negligible (far less than 1,000 t) or unavailable until the year 1976, as shown.

In the 1970s refrigerated storage and transport became available,[39] bringing fresh produce and seafood to areas away from farms or seaports. Foods like sashimi became daily fare for Japanese people, and the green shiso leaves, developed as a garnish for sashimi, quickly began to gain ground.

The No. 1 producer of produce-type shiso among the 47 prefectures in Japan is Aichi Prefecture, boasting 3,852 tons, representing 37.0% of national production (based on latest available FY 2008 data).[71] Another source uses greenhouse-grown production of 3,528 tons as the figure better representation actual ōba production, and according to this, the prefecture has a 56% share.[39][72] The difference in percentage is an indicator that in Aichi, the leaves are 90% greenhouse produced, whereas nationwide the ratio is 60:40 in favor of indoors over open fields.[73]

As aforestated, Toyohashi, Aichi is the city which produces the most shiso vegetable in Japan.[38][74] They are followed in ranking by Namegata, Ibaraki.

There seems to be a growth spurt for shiso crops grown for industrial use. The data shows the following trend for crops targeted for oil and perfumery.[75]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Perilla frutescens var. crispa. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Perilla frutescens var. crispa |

Sources

- ↑ "Perilla frutescens var. crispa (Thunb.) H.Deane". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 1 October 2018 – via The Plant List.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 2008, "shiso". WordReference. Retrieved April 1, 2012. , "shiso n. ... chiefly used as a herb in Japanese cookery"

- 1 2 Tucker & DeBaggio (2009), p. 389, "name beefsteak plant.. from the bloody purple-red color.."

- ↑ Hosking, Richard (2015). "egoma, shiso". A Dictionary of Japanese Food: Ingredients & Culture. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 37, 127.

- ↑ Hall, Clifford, III; Fitzpatrick, Kelley C.; Kamal-Eldin, Afaf, "Flax, Perilla, and Camelina Seed Oils: α-Linolenic Acid-rich Oils", Gourmet and Health-Promoting Specialty Oils, p. 152

- ↑ Burum, Linda (1992), A Guide to Ethnic Food in Los Angeles, HarperPerennial, p. 70

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Heibonsha (1969)

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), pp. 1–2, 10–11.

- ↑ Grbic, Nikolina; Pinker, Ina; Böhme, Michael (2016). "The Nutritional Treasure of Leafy Vegetables-Perilla frutescens" (PDF). Conference on International Research on Food Security, Natural Resource Management and Rural Development. Vienna, Austria.

According to scientific nomenclature of Perilla two varieties are described: variety frutescens - mainly used in Korea as fresh vegetable or for making pickles, and variety crispa - a strongly branching crop mainly used in Japan and Vietnam, with smaller curly leaves rich in anthocyanins.

- ↑ Hu (2005), p. 651.

- ↑ murasaki

- ↑ yomigaeru

- ↑ Shinmura (1976), Kōjien 2nd ed. revised. (1st ed. 1955, the linguist who edited the dictionary died 1967). Definition of shiso translates to: "Annual of mint family. Native to China. Grows to 60cm. Stalk is rectangular, leaves are purple-red and fragrant.. (description of flower and fruit).. Leaves and fruit..used as an edible aromatic, and to color umeboshi. Occurs in green and chirimen (ruffle-leaved) forms."

- 1 2 anonymous (March 1855), "List of Select and New Florists' Flowers" (google), The Floricultural cabinet, and florists' magazine, London: Simpkin,Marshall, & Co., 23: 62 "Perilla Nankinesnsis, a new and curious plant with crimsn leaves.."; An earlier issue (Vol. 21, Oct. 1853) , p.240, describe it being grown among the "New Annuals in the Horticultural Society's Garden"

- 1 2 Wilson et al. (1977) apud Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), p. 1

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vaughan, John; Geissler, Catherine, eds. (2009). The New Oxford Book of Food Plants (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 340. ISBN 9780199549467.

- ↑ Kays, S. J. (2011). Cultivated Vegetables of the World:: A Multilingual Onomasticon. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. pp. 180–181, 677–678. ISBN 9789086861644.

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), p. 3.

- ↑ Duke (1988) apud Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), p. 1

- ↑ Foster & Yue (1992), pp. 306-308.

- ↑ Roecklein, John C.; Leung, PingSun, eds. (1987). A Profile of Economic Plants. New Brunswick, U.S.A: Transaction Publishers. p. 349. ISBN 9780887381676.

- ↑ Blaschek, Wolfgang; Hänsel, Rudolf; Keller, Konstantin; Reichling, Jürgen; Rimpler, Horst; Schneider, Georg, eds. (1998). Hagers Handbuch der Pharmazeutischen Praxis (in German) (3 ed.). Berlin: Gabler Wissenschaftsverlage. pp. 328-. ISBN 9783540616191.

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), p. 37.

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), p. 3, citing:Tanaka, K. (1993), "Effects of Periilla", My Health (8): 152–153 (in Japanese).

- ↑ Nitta, Lee & Ohnishi (2003), pp. 245-

- ↑ Tucker & DeBaggio (2009), p. 389.

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), p. 151.

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), p. 11.

- ↑ Heibonsha (1969), p. 246.

- ↑ Heibonsha (1969) Encycl. states egoma seeds are about 1.2 mm, slightly larger than shiso seeds. However, egoma seeds being grown currently can be much larger.

- ↑ Oikawa & Toyama (2008), p. 5, egoma, sometimes classed P. frutescens var. Japonica, exhibited sizes of sieve caliber between 1.4 mm ~ 2.0 mm for black seeds and sieve caliber bewtween 1.6 mm ~ 2.0 mm for white seeds.

- ↑ This is based on 650 seeds/gram reported by a purveyor Nicky's seeds; this is in ballpark with "The ABCs of Seed Importation into Canada". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Retrieved 2012-03-31. also quotes 635 per gram, though it is made unclear which variety

- ↑ Shimbo (2001), pp. 142-

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), p. 151: "Kondo (1931) and Kuroda and Wada (1935) isolated an anthocyanin pigment from purple Perilla leaves and gave it the name shisonin".

- 1 2 Tsuji & Fisher (2007), p. 89

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Kawakami, Kōzō; Nishimura, Motozaburō (1990). Nihon ryōri yurai jiten 日本料理由来事典. 1. Dōhōsha. ISBN 978-4-8104-9116-6. ISBN 4-8104-9116-1. , quoted by "Kotoba no hanashi 1249: Ōba to shiso" ことばの話1249「大葉と紫蘇」. Toshihiko Michiura's Heisei kotoba jijo. 2003-06-26. Retrieved 2012-04-02. : "..一九六一(昭和三十六)年ごろ、静岡県の、あるツマ物生産組合が、青大葉ジソの葉を摘んでオオバの名で大阪の市場に出荷.."

- 1 2 "JA Toyohashi brand" JA豊橋ブランド. 2012. Archived from the original on 2011-01-27. Retrieved 2012-04-02. , under heading "Tsumamono nippon-ichi"(つまもの生産日本一) states Toyhashi is Japan's No. 1 producer of both edible chrysanthemums and shiso

- 1 2 3 4 Okashin (2012) website pdf, p.174

- ↑ Kindaichi (1997); 2nd ed.:「紫蘇一畑に作る一年草。ぎざぎざのある葉は紫(緑)色..」

- ↑ Hyo-Sun Shin, in Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), pp. 93-, citing Tsuyuki et al. (1978)

- ↑ Esaki, Osamu (2006). "Seikatsu shūkan yobō no tame no shokuji/undō ryōhō no sayōkijo ni kansuru kenkyū" 生活習慣病予防のための食事・運動療法の作用機序に関する研究. Proceedings of the JSNFS. 59 (5): 326. gives 58%

- ↑ Hiroi (2009), p. 35, gives 62.3% red, 65.4% green shiso

- ↑ Liu, J.-H.; Steigel, A.; Reininger, E.; Bauer, R. (2000). "Two new prenylated 3-benzoxepin derivatives as cyclooxygenase inhibitors from Perilla frutescens var. acuta". J. Nat. Prod. 63 (3): 403–405. doi:10.1021/np990362o.

- 1 2 3 Ito, Michiho (2008). "Studies on Perilla Relating to Its Essential Oil and Taxonomy". In Matsumoto, Takumi. Phytochemistry Research Progress. New York: Nova Biomedical Books. pp. 13–30. ISBN 9781604562323.

- 1 2 Tucker & DeBaggio (2009), p. 389

- ↑ O'Brien-Nabors (2011), p. 235.

- ↑ Kinghorn and Compadre (2001) apud O'Brien-Nabors (2011), p. 235.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-05-10. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

- 1 2 Mouritsen (2009), pp. 110–112, Sushi book written by a Danish biophysicist

- ↑ Ogawa, Toshio(小川敏男 (1978). つけもの(tsukemono) (preview). Hoiku-sha (保育社). p. 115. ISBN 978-4-586-50423-7. ISBN 4-586-50423-4. gives an illustrated guide to making shibazuke (text Japanese)

- ↑ Larkcom (2007), Oriental Vegetables

- ↑ Fujita, Satoshi(藤田智) (2009). 体においしい野菜づくり (preview). PHP研究所. p. 78. ISBN 978-4-569-70610-8. ISBN 4-569-70610-X. , written by a horticulture professor at Keisen University and well-known gardening tipster on TV. quote:"発芽した双葉「芽ジソ(青ジソのアオメ、赤ジソのムラメ)」"

- ↑ Tsuji & Fisher (2007), p. 164 commits this error, even though the book explains elsewhere, under the section dedicated to shiso, that the "tiny sprouts (mejiso)" are used (p.89).

- ↑ Ishikawa (1997), p. 108. Photograph shows both green shiso sprouts (aome) and slightly larger red shiso sprouts (mura me) with true leaves

- ↑ Google search using keywords "芽ジソ"+"間引き" (Japanese for mejiso and thinning) turns up many examples, but mostly blogs, etc.

- ↑ Andoh & Beisch (2005), pp. 12, 26–7

- ↑ Used as such by Japanese-American author, Andoh & Beisch (2005), pp. 26-7

- ↑ "名前の由来 (origin to its name)". Mishima foods webpage. Archived from the original on 2012-05-15.

- ↑ Shinmura (1976), Kōjien 2nd ed. revised

- ↑ Rutledge, Bruce. Kūhaku & Other Accounts from Japan (preface). pp. 218–9. ISBN 978-0-974199-50-4. ISBN 0-974199-50-8. gives this tarako and shiso spaghetti recipe

- 1 2 이, 영득 (2010). San-namul deul-namul dae baekgwa 산나물 들나물 대백과 (in Korean). 황소걸음. ISBN 978-89-89370-68-0 – via Naver.

- ↑ Nitta, Miyuki; Lee, Ju Kyong; Ohnishi, Ohmi (April 2003). "Asian Perilla crops and their weedy forms: Their cultivation, utilization and genetic relationships". Economic Botany. 57 (2): 245–253. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0245:APCATW]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ http://www.evergreenseeds.com/vipeitto.html

- ↑ "Vietnamese Perilla (Tia To)". localharvest.org. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ Dombrain, H. H. (1862), Floral Magazine (google), 2, London: Lovell Reeve , Pl. 96

- ↑ Dombrain, H. H. (1862), "New or rare plants" (google), The Gardener's Monthly and Horticultural Advertiser, London: Lovell Reeve, 4: 181

- ↑ Maloy, Bridget (1867), "The Horticultural Department:The Culture of Flowers" (google), The Cultivator & Country Gentleman, Alban, NY: Luther Tucker & Son, 29: 222 , "Perilla nankinensis was one of the first of the many ormanental foliaged plants brought into the gardens and greenhouses of this country within few years. "

- ↑ Foster & Yue (1992), pp. 306-8 gives mid-19th century as introductory period into the US.

- ↑ MAFFstat (2012b), FY2009, title: "Vegetables: Domestic Production Breakdown (野菜の国内生産量の内訳)" , Excel button (h001-21-071.xls)

- ↑ Aichi Prefecture (2011). "愛知の特産物(平成21年)". Retrieved 2012-04-02. , starred data is FY2008 data.

- ↑ Both these numbers square with MAFFstat (2012a) figures

- ↑ MAFFstat (2012a)

- ↑ This can be derived from MAFFstat (2012a), with minimal data analysis. Aichi produces four times as much as the 2nd ranked Ibaraki Prefecture and Toyohashi grew 48% of it, so about double any other prefectural total.

- ↑ MAFFstat (2012c)

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Toyohashi Engei Nōkyō (豊橋園芸農協).

- ↑ Yu, Kosuna & Haga (1997), pp. 10–11 also glosses mejiso "bud Perilla".

References

- (Herb books)

- Larkcom, Joy (2007). Oriental Vegetables (preview). Frances Lincoln. pp. 112-. ISBN 978-0-7112-2612-8. ISBN 0-7112-2612-1.

- (Cookbooks)

- Andoh, Elizabeth; Beisch, Leigh (2005), Washoku: recipes from the Japanese home kitchen (google), Random House Digital, Inc., p. 47, ISBN 978-1-58008-519-9

- Mouritsen, Ole G. (2009). Sushi: Food for the Eye, the Body and the Soul. Jonas Drotner Mouritsen. Springer. pp. 110–112. ISBN 978-1-4419-0617-5. ISBN 1-4419-0617-7.

- Shimbo, Hiroko (2001), The Japanese kitchen: 250 recipes in a traditional spirit (preview), Harvard Common Press, ISBN 978-1-55832-177-9, ISBN 1-55832-177-2

- Tsuji, Shizuo; Fisher, M.F.K. (2007), Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art (preview), Kodansha International, p. 89, ISBN 978-4-7700-3049-8, ISBN 4-7700-3049-5

- Ishikawa, Takayuki (1997). Ninki no nihon ryōri: ichiryū itamae ga tehodoki suru 人気の日本料理―一流板前が手ほどきする [Chef's Best Choice Japanese Cuisine]. Bessatsu Kateigaho mook. Sekaibunkasha. ISBN 978-4-418-97143-5. ISBN 4-418-97143-2.

- (Nutrition and chemistry)

- O'Brien-Nabors, Lyn (2011), Alternative Sweeteners (preview), CRC Press, p. 235, ISBN 978-1-4398-4614-8

- Yu, He-Ci; Kosuna, Kenichi; Haga, Megumi (1997), Perilla: the genus Perilla, Medicinal and aromatic plants--industrial profiles, 2, CRC Press, ISBN 978-90-5702-171-8, ISBN 90-5702-171-4 , pp. 26–7

- (Japanese dictionaries)

- Shinmura, Izuru (1976). Kōjien 広辞苑. Iwanami.

- Satake, Yoshisuke; Nishi, Sadao; Motoyama, Tekishū (1969) [1968]. "Shiso" しそ. Sekai hyakka jiten. 10. Heibonsha. pp. 246–7. (in Japanese)

- Kindaichi, Kyōsuke (1997), Shin Meikai Kokugo Jiten 新明解国語辞典 (5th ed.), Sanseido, ISBN 978-4-385-13099-6

- (Japanese misc. sites)

- Okashin. "Aichi no jiba sangyō" あいちの地場産業. Archived from the original on 2007-08-12. Retrieved 2012-04-02. : right navbar "9 農業(野菜)"

- (Ministry statistics)

- MAFFstat (2012a). "地域特産野菜生産状況調査(regional specialty vegetables production status study". Retrieved 2012-04-02. . It gives to ink to H12 (FY2000), H14 (FY2002), H16 (FY2004), H18 (FY2006), H20 (FY2008) figures. They are not direct links to Excel sheets, but jump to TOC pages at e-stat.go.jp site. The latest available is TOC for The FY2008(年次) Regional Specialty Vegetable Production Status Study, published 11/26/2010. Under Category 3-1 Vegetables by crop and prefecture: acreage, harvest yield, etc. (野菜の品目別、都道府県別生産状況 作物面積収穫量等), find 10th crop shiso (しそ), and click Excel button to open p008-20-014.xls. Under Category 3-2, you can also retrieve Vegetable by crop and prefecture: major cutivars at major-producing municipalities (野菜の品目別、都道府県別生産状況 主要品種主要市町村 ).

- MAFFstat (2012b). "食料需給表 (food supply & demand tables)". Retrieved 2012-04-02. . for data (h001-21-071.xls).

- MAFFstat (2012c). "特産農作物の生産実績調査(specialty vegetables production realized study)". Retrieved 2012-04-02. . Links to H14 (FY2000) - H19 (FY2007) biannual figures, not direct link to Excel but jump to TOC pages at e-stat.go.jp site. The latest available is TOC for The FY2007(年次) Specialty Vegetable Production Realized Study, published 3/23/2010. Locate 1-1-10 is Shiso (しそ), where heading reads " Industrial crop sown acreage and production" (工芸作物の作付面積及び生産量, and click Excel button to open p003-19-010.xls.

- O'Brien-Nabors, Lyn (2011), Alternative Sweeteners (preview), CRC Press, p. 235, ISBN 9781439846148

- Tucker, Arthur O.; DeBaggio, Thomas (2009), The Encyclopedia of Herbs: a comprehensive reference to herbs of flavor and (preview), Timber Press, p. 389, ISBN 978-0-88192-994-2

- Channell, BJ; Garst, JE; Linnabary, RD; Channell, RB (5 August 1977), "Perilla ketone: a potent lung toxin from the mint plant, Perilla frutescens Britton", Science, 197 (4303): 573–574, Bibcode:1977Sci...197..573W, doi:10.1126/science.877573, PMID 877573

- Foster, Steven; Yue, Chongxi (1992), Herbal emissaries: bringing Chinese herbs to the West : a guide to gardening, Inner Traditions / Bear & Co., pp. 306–8, ISBN 9780892813490

- Hu, Shiu-ying (2005), Food plants of China, 1, Chinese University Press, ISBN 9789629962296

- Oikawa, Kazushi; Toyama, Ryo (2008), "Analysis of Nutrition and the Functionality Elements in Perilla Seeds", 岩手県工業センター研究報告, 15 pdf (in Japanese except abstract)

- Imamura, Keiji (1996), Prehistoric Japan - New Perspectives on Insular East Asia, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 107–8, ISBN 9780824818524

- Habu, Junko (2004), Ancient Jomon of Japan, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge Press, p. 59, ISBN 9780521776707

External links

- "Portals Site of Official Statistics of Japan". E-stat-go-jp. 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2012-04-02. . This site is nominally available in English, but the search engine is not very robust.