Queen Anne's War

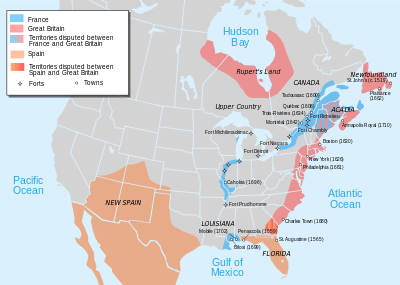

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in England's Thirteen American Colonies; in Europe, it is viewed as the North American theater of the War of the Spanish Succession. It was fought between France and England (plus England's colonial forces) for control of the American continent, while the War of the Spanish Succession was primarily fought in Europe. The war also involved numerous American Indian tribes allied with each nation, and Spain was allied with France. It is also known as the Third Indian War[1] or in France as the Second Intercolonial War.[2] It was fought on three fronts:

- Spanish Florida and the English Province of Carolina attacked one another, and the English forces engaged the French based at Mobile, Alabama in a proxy war involving allied Indians on both sides. The southern war did not result in significant territorial changes, but it had the effect of nearly wiping out the Indian population of Spanish Florida, including parts of southern Georgia, and destroying the network of Spanish missions in Florida.

- The English colonies of New England fought against French and Indian forces based in Acadia and Canada. Quebec City was repeatedly targeted by British expeditions, and the Acadian capital Port Royal was taken in 1710. The French and Wabanaki Confederacy sought to thwart New England expansion into Acadia, whose border New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine.[3] Toward this end, they executed raids against targets in the Province of Massachusetts Bay (including Maine), most famously the raid on Deerfield in 1704.

- English colonists based at St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador disputed control of the island with the French based at Plaisance. Most of the conflict consisted of economically destructive raids on settlements. The French successfully captured St. John's in 1709, but the British quickly reoccupied it after the French abandoned it.

The Treaty of Utrecht ended the war in 1713, following a preliminary peace in 1712. France ceded the territories of Hudson Bay, Acadia, and Newfoundland to Britain while retaining Cape Breton Island and other islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Some terms were ambiguous in the treaty, and concerns of various Indian tribes were not included, thereby setting the stage for future conflicts.

Background

War broke out in 1701 following the death of King Charles II over who should succeed him to the Spanish throne. The war at first was restricted to a few powers in Europe, but it widened in May 1702 when England declared war on Spain and France.[4] The hostilities in North America were further encouraged by existing frictions along the frontier areas separating the colonies of these powers. This dis-harmony was most pronounced along the northern and southwestern frontiers of the English colonies, which then stretched from the Province of Carolina in the south to the Province of Massachusetts Bay in the north, with additional colonial settlements or trading outposts on Newfoundland and at Hudson Bay.[5]

The total population of the English colonies at the time has been estimated at 250,000, with Virginia and New England dominating.[6] The population centers of these colonies were concentrated along the coast, with small settlements inland, sometimes reaching as far as the Appalachian Mountains.[7] Most European colonists knew very little of the interior of the continent, to the west of the Appalachians and south of the Great Lakes. This area was dominated by Indian tribes, although French and English traders had penetrated the area. Spanish missionaries in La Florida had established a network of missions to convert the indigenous inhabitants to Roman Catholicism.[8] The Spanish population was relatively small (about 1,500), and the Indian population to whom they ministered has been estimated to number 20,000.[9] French explorers had located the mouth of the Mississippi River, near which they established a small colonial presence in 1699 at Fort Maurepas (near present-day Biloxi, Mississippi).[10] From there they began to establish trade routes into the interior, establishing friendly relations with the Choctaw, a large tribe whose enemies included the British-allied Chickasaw.[11] All of these populations had suffered to some degree from the introduction of Eurasian infectious diseases such as smallpox by early explorers and traders.[12]

The arrival of the French in the south threatened existing trade links that Carolina colonists had established into the interior, creating tension among all three powers. France and Spain, allies in this conflict, had been on opposite sides of the recently ended Nine Years' War.[13] Conflicting territorial claims between Carolina and Florida south of the Savannah River were overlaid by animosity over religious divisions between the Roman Catholic Spanish and the Protestant English along the coast.[14]

To the north, the conflict held a strong economic component in addition to territorial disputes. Newfoundland was the site of a British colony based at St. John's, and the French colonial base was at Plaisance, with both sides also holding a number of smaller permanent settlements. The island also had many seasonal settlements used by fishermen from Europe.[15] These colonists numbered fewer than 2,000 English and 1,000 French permanent settlers (and many more seasonal visitors) who competed with one another for the fisheries of the Grand Banks, which were also used by fishermen from Acadia (then encompassing all of present-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) and Massachusetts.[16][17]

The border area between Acadia and New England remained uncertain despite battles along the border throughout King William's War. New France defined the border of Acadia as the Kennebec River in southern Maine.[3] There were Catholic missions at Norridgewock and Penobscot and a French settlement in Penobscot Bay near the site of modern Castine, Maine, which had all been bases for attacks on New England settlers migrating toward Acadia during King William's War.[18] The frontier areas between the Saint Lawrence River and the primarily coastal settlements of Massachusetts and New York were still dominated by Indians (primarily Abenaki and Iroquois), and the Hudson River–Lake Champlain corridor had also been used for raiding expeditions in both directions in earlier conflicts. The threat of Indians had receded somewhat because of reductions in the population as a result of disease and the last war, but they still posed a potent threat to outlying settlements.[19]

The Hudson Bay territories (known to the English as Prince Rupert's Land) were not significantly fought over in this war. They had been a scene of much dispute by competing French and English companies starting in the 1680s, but the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick left France in control of all but one outpost on the bay. The only incident of note was a French attack on the outpost of Fort Albany in 1709.[20][21] The Hudson's Bay Company was unhappy that Ryswick had not returned its territories, and it successfully lobbied for the return of its territories in the negotiations that ended this war.[22]

Technology and organization

_-_Geographicus_-_AmeriqueSeptentrionale-covensmortier-1708.jpg)

Military technology used in North America was not as developed as it was in Europe. Only a few colonial settlements had stone fortifications at the start of the war, such as St. Augustine, Florida, Boston, Quebec City, and St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, although Port Royal's fortifications were completed early in the war.[23] Some frontier villages were protected by wooden palisades, but many had little more than fortified wooden houses with gun ports through which defenders could fire, and overhanging second floors from which they might fire down on attackers trying to break in below.[24] Europeans and colonists were typically armed with smooth-bore muskets that had a maximum range of about 100 yards (91 m) but were inaccurate at ranges beyond half that distance. Some colonists also carried pikes, while tribal warriors were either supplied with European arms or were armed with more primitive weapons such as tomahawks and bows. A small number of colonists had training in the operation of cannon and other types of artillery which were the only effective weapons for attacking significant stone or wooden defenses.[25]

English colonists were generally organized into militia companies, and their colonies had no regular military presence[25] beyond a small number in some of the communities of Newfoundland.[26] The French colonists were also organized into militias, but they also had a standing defense force called the troupes de la marine. This force consisted of some experienced officers and was manned by recruits sent over from France numbering between 500 and 1,200. They were spread throughout the territories of New France, with concentrations in the major population centers.[27] Spanish Florida was defended by a few hundred regular troops; Spanish policy was to pacify the Indians in their territory and not to provide them with weapons. Florida held an estimated 8,000 Indians before the war, but this was reduced to 200 after English colonist raids made early in the war.[28]

Course of the war

Florida and Carolina

Prominent French and English colonists understood at the turn of the 18th century that control of the Mississippi River would have a significant role in future development and trade, and each developed visionary plans to thwart the other's activities. French Canadian explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville had developed a "Project sur la Caroline" in the aftermath of the previous war which called for establishing relationships with Indians in the Mississippi watershed and then leveraging those relationships to push the English colonists off the continent, or at least limit them to coastal areas. In pursuit of this grand strategy, he rediscovered the mouth of the Mississippi (which had first been found by La Salle in 1670) and established Fort Maurepas in 1699. From this base and Fort Louis de la Mobile (founded in 1702),[29] he began to establish relationships with the local Choctaw, Chickasaw, Natchez, and other tribes.[30]

English colonial traders and explorers from Carolina had established a substantial trading network across the southeastern part of the continent that extended all the way to the Mississippi.[31] Its leaders had little respect for the Spanish in Florida, but they understood the threat posed by the French arrival on the coast. Both Carolina governor Joseph Blake and his successor James Moore articulated visions of expansion to the south and west at the expense of French and Spanish interests.[32]

Iberville had approached the Spanish in January 1702 before the war broke out in Europe, recommending that the Apalachee warriors be armed and sent against the English colonists and their allies. The Spanish organized an expedition under Francisco Romo de Uriza which left Pensacola, Florida in August for the trading centers of the Carolina back country. The English colonists had advance warning of the expedition and organized a defense at the head of the Flint River, where they routed the Spanish-led force with some 500 Spanish-led Indians killed or captured.[33]

Carolina's Governor Moore received notification concerning the hostilities, and he organized and led a force against Spanish Florida.[34] 500 English colonial soldiers and militia and 300 Indians captured and burned the town of St. Augustine, Florida in the Siege of St. Augustine (1702).[35] The English were unable to take the main fortress and withdrew when a Spanish fleet arrived from Havana.[34] In 1706, Carolina successfully repulsed an attack on Charles Town by a combined Spanish and French amphibious force sent from Havana.[36]

The Apalachee and Timucua of Spanish Florida were virtually wiped out in a raiding expedition by Moore that became known as the Apalachee Massacre of 1704.[37] Many of the survivors of these raids were relocated to the Savannah River where they were confined to reservations.[38] Raids continued in the following years consisting of large Indian forces, sometimes including a small number of white men;[39] this included major expeditions directed at Pensacola in 1707 and Mobile in 1709.[40][41] The Muscogee (Creek), Yamasee, and Chickasaw were armed and led by English colonists, and they dominated these conflicts at the expense of the Choctaw, Timucua, and Apalachee.[38]

New England and Acadia

Throughout the war, New France and the Wabanaki Confederacy were able to thwart New England expansion into Acadia, whose border New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine.[3] In 1703, Michel Leneuf de la Vallière de Beaubassin commanded a few French Canadians and 500 Indians of the Wabanaki Confederacy, and they led attacks against New England settlements from Wells to Falmouth (present-day Portland, Maine) in the Northeast Coast Campaign.[42] They killed or captured more than 300 settlers.

In February 1704, Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville led 250 Abenaki and Caughnawaga Indians and 50 French Canadians in a raid on Deerfield in the Province of Massachusetts Bay and destroyed the settlement, killing and capturing many colonists. More than 100 captives were taken on an overland journey hundreds of miles north to the Caughnawaga mission village near Montreal, where most of the children who survived were adopted by the Mohawk people. Several adults were later redeemed or released in negotiated prisoner exchanges, including the minister, who tried for years without success to ransom his daughter. She became fully assimilated, marrying a Mohawk man.[43] There was an active market in human trafficking of the captive colonists during these years, and communities raised funds to ransom their citizens from Indian captivity.

New England colonists were unable to effectively combat these raids, so they retaliated by launching an expedition against Acadia led by the famous American Indian fighter Benjamin Church. The expedition raided Grand Pré, Chignecto, and other settlements.[43] French accounts claim that Church attempted an attack on Acadia's capital of Port Royal, but Church's account of the expedition describes a war council in which the expedition decided against making an attack.[44]

Father Sébastien Rale was widely suspected of inciting the Norridgewock tribe against the New Englanders, and Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley put a price on his head. In the winter of 1705, 275 British soldiers under the command of Colonel Winthrop Hilton were dispatched to seize Rale and sack the village. The priest was warned in time, however, and escaped into the woods with his papers, but the militia burned the village and church.[45]

French and Wabanaki Confederacy raiding activity continued in northern Massachusetts in 1705, against which the English colonists were unable to mount an effective defense. The raids happened too quickly for defensive forces to organize, and reprisal raids usually found tribal camps and settlements empty. There was a lull in the raiding while the French and English leaders negotiated the exchange of prisoners, with only limited success.[46] Raids by Indians persisted until the end of the war, sometimes with French participation.[47]

In May 1707, Governor Dudley organized an expedition to take Port Royal led by John March. However, 1,600 men failed to take the fort by siege, and a follow-up expedition in August was also repulsed.[48] In response, the French developed an ambitious plan to raid most of the New Hampshire settlements on the Piscataqua River. However, much of the Indian support needed never materialized, and the Massachusetts town of Haverhill was raided instead.[49] In 1709, New France governor Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil reported that two-thirds of the fields north of Boston were untended because of French and Indian raids. French-Indian war parties were returning without prisoners because the New England colonists stayed in their forts and would not come out.[50]

In September 1710, 3,600 British and colonial forces led by Francis Nicholson finally captured Port Royal after a siege of one week. This ended official French control of the peninsular portion of Acadia (present-day mainland Nova Scotia),[51] although resistance continued until the end of the war.[52] Resistance by the Wabanaki Confederation continued in the 1711 Battle of Bloody Creek and raids along the Maine frontier.[53] The remainder of Acadia (present-day eastern Maine and New Brunswick) remained disputed territory between New England and New France.[54]

Expeditions against New France

The French in New France's heartland of Canada opposed attacking the Province of New York. They were reluctant to arouse the Iroquois, whom they feared more than they did the British colonists and with whom they had made the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701. New York merchants were opposed to attacking New France because it would interrupt the lucrative Indian fur trade, much of which came through New France.[55] The Iroquois maintained their neutrality throughout the conflict, despite Peter Schuyler's efforts to interest them in the war.[56] (Schuyler was Albany's commissioner of Indians.)

Francis Nicholson and Samuel Vetch organized an ambitious assault against New France in 1709, with some financial and logistical support from the queen. The plan involved an overland assault on Montreal via Lake Champlain and a sea-based assault by naval forces against Quebec. The land expedition reached the southern end of Lake Champlain, but it was called off when the promised naval support never materialized for the attack on Quebec.[57] (Those forces were diverted to support Portugal.) The Iroquois had made vague promises of support for this effort, but successfully delayed sending support until it seemed clear that the expedition was going to fail. After this failure, Nicholson and Schuyler traveled to London accompanied by King Hendrick and other sachems to arouse interest in the North American frontier war. The Indian delegation caused a sensation in London, and Queen Anne granted them an audience. Nicholson and Schuyler were successful in their endeavor: the queen gave support for Nicholson's successful capture of Port Royal in 1710.[58] With that success under his belt, Nicholson again returned to England and gained support for a renewed attempt on Quebec in 1711.[51]

The plan for 1711 again called for land and sea-based attacks, but its execution was a disaster. A fleet of 15 ships of the line and transports carrying 5,000 troops led by Admiral Hovenden Walker arrived at Boston in June,[51] doubling the town's population and greatly straining the colony's ability to provide necessary provisions.[59] The expedition sailed for Quebec at the end of July, but a number of its ships foundered on the rocky shores near the mouth of the Saint Lawrence in the fog. More than 700 troops were lost, and Walker called off the expedition.[60] In the meantime, Nicholson had departed for Montreal overland but had only reached Lake George when word reached him of Walker's disaster, and he also turned back.[61] In this expedition, the Iroquois provided several hundred warriors to fight with the English colonists, but they simultaneously sent warnings to the French about the expedition, effectively playing both sides of the conflict.[62]

Newfoundland

Newfoundland's coast was dotted with small French and English communities, with some fishing stations occupied seasonally by fishermen from Europe.[63] Both sides had fortified their principal towns, the French at Plaisance on the western side of the Avalon Peninsula, the English at St. John's on Conception Bay.[64] During King William's War, d'Iberville had destroyed most of the English communities in 1696–97,[65] and the island again became a battleground in 1702. In August of that year, an English fleet under the command of Commodore John Leake descended on the outlying French communities but made no attempts on Plaisance.[66] During the winter of 1705, Plaisance's French governor Daniel d'Auger de Subercase retaliated, leading a combined French and Mi'kmaq expedition that destroyed several English settlements and unsuccessfully besieged Fort William at St. John's. The French and their Indian allies continued to harry the English throughout the summer and did damages to the English establishments claimed at £188,000.[67] The English sent a fleet in 1706 that destroyed French fishing outposts on the island's northern coasts.[68] In December 1708, a combined force of French, Canadian, and Mi'kmaq volunteers captured St. John's and destroyed the fortifications. They lacked the resources to hold the prize, however, so they abandoned it, and St. John's was reoccupied and refortified by the English in 1709. (The same French expedition also tried to take Ferryland, but it successfully resisted.)[69]

English fleet commanders contemplated attacks on Plaisance in 1703 and 1711 but did not make them, the latter by Admiral Walker in the aftermath of the disaster at the mouth of the St. Lawrence.[70]

Peace

In 1712, Britain and France declared an armistice, and a final peace agreement was signed the following year. Under terms of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, Britain gained Acadia (which they renamed Nova Scotia), sovereignty over Newfoundland, the Hudson Bay region, and the Caribbean island of St. Kitts. France recognized British suzerainty over the Iroquois[71] and agreed that commerce with American Indians farther inland would be open to all nations.[72] It retained all of the islands in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, including Cape Breton Island, and retained fishing rights in the area, including rights to dry fish on the northern shore of Newfoundland.[73]

By the later years of the war, many Abenakis had tired of the conflict despite French pressures to continue raids against New England targets. The peace of Utrecht, however, had ignored Indian interests, and some Abenaki expressed willingness to negotiate a peace with the New Englanders.[74] Governor Dudley organized a major peace conference at Portsmouth, New Hampshire (of which he was also governor). In negotiations there and at Casco Bay, the Abenakis objected to British assertions that the French had ceded to Britain the territory of eastern Maine and New Brunswick, but they agreed to a confirmation of boundaries at the Kennebec River and the establishment of government-run trading posts in their territory.[75] The Treaty of Portsmouth was ratified on July 13, 1713 by eight representatives of some of the tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy; however, it included language asserting British sovereignty over their territory.[76] Over the next year, other Abenaki tribal leaders also signed the treaty, but no Mi'kmaq ever signed it or any other treaty until 1726.[77]

Consequences

Southern colonies

Spanish Florida never really recovered its economy or population from the effects of the war,[78] and it was ceded to Britain in the 1763 Treaty of Paris following the Seven Years' War.[79] Indians who had been resettled along the Atlantic coast chafed under British rule, as did those allied to the British in this war. This discontentment flared into the 1715 Yamasee War that posed a major threat to South Carolina's viability.[80] The loss of population in the Spanish territories contributed to the 1732 founding of the Province of Georgia, which was granted on territory that Spain had originally claimed, as was also the case with Carolina.[81] James Moore took military action against the Tuscaroras of North Carolina in the Tuscarora War which began in 1711, and many of them fled north as refugees to join their linguistic cousins the Iroquois.[82]

The economic costs of the war were high in some of the southern English colonies, including those that saw little military activity. Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania to a lesser extent, were hit hard by the cost of shipping their export products (primarily tobacco) to European markets, and they also suffered because of several particularly bad harvests.[83] South Carolina accumulated a significant debt burden to finance military operations.[84]

New England

Massachusetts and New Hampshire were on the front line of the war, yet the New England colonies suffered less economic damage than other areas. Some of the costs of the war were offset by the importance of Boston as a center of shipbuilding and trade, combined with a financial windfall caused by the crown's military spending on the 1711 Quebec expedition.[84]

Newfoundland and Acadia

The loss of Newfoundland and Acadia restricted the French presence on the Atlantic to Cape Breton Island. French were resettled there from Newfoundland, creating the colony of Île-Royale, and France constructed the Fortress of Louisbourg in the following years.[71] This presence plus the rights to use the Newfoundland shore resulted in continued friction between French and British fishing interests, which was not fully resolved until late in the 18th century.[85] The economic effects of the war were severe in Newfoundland, with the fishing fleets significantly reduced.[86] The British fishing fleet began to recover immediately after the peace was finalized,[87] and they attempted to prevent Spanish ships from fishing in Newfoundland waters, as they previously had. However, many Spanish ships were simply reflagged with English straw owners to evade British controls.[88]

The British capture of Acadia had long-term consequences for the Acadians and Mi'kmaq living there. Britain's hold on Nova Scotia was initially quite tenuous, a situation on which French and Mi'kmaq resistance leaders capitalized.[89] British relations with the Mi'kmaq after the war developed in the context of British expansion in Nova Scotia[90] and also along the Maine coast, where New Englanders began moving into Abenaki lands, often in violation of previous treaties. Neither the Abenakis nor the Mi'kmaq were recognized in the Treaty of Utrecht, and the 1713 Portsmouth treaty was interpreted differently by them than by the New England signatories, so the Mi'kmaq and Abenakis resisted these incursions into their lands. This conflict was increased by French intriguers such as Sébastien Rale, and eventually they developed into Father Rale's War (1722–1727).[91]

British relations were also difficult with the nominally conquered Acadians. They resisted repeated British demands to swear oaths to the British crown, and eventually this sparked an exodus by the Acadians to Île-Royale and Île-Saint-Jean (present-day Prince Edward Island).[92] By the 1740s, French leaders such as Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre orchestrated a guerrilla war with their Mi'kmaq allies against British attempts to expand Protestant settlements in peninsular Nova Scotia.[93]

Friction also persisted between France and Britain over Acadia's borders. The boundaries were unclear as laid out by the treaty, which even the French had never formally described. France insisted that only the Acadian peninsula was included in the treaty (modern Nova Scotia except Cape Breton Island) and that they retained the rights to modern New Brunswick.[54] The disputes over Acadia flared into open conflict during King George's War in the 1740s and were not resolved until the British conquest of all French North American territories in the Seven Years' War.[94]

Trade

The French did not fully comply with the commerce provisions of the Treaty of Utrecht. They attempted to prevent English trade with remote Indian tribes, and they erected Fort Niagara in Iroquois territory. French settlements continued to grow on the Gulf Coast, with the settlement of New Orleans in 1718 and other (unsuccessful) attempts to expand into Spanish-controlled Texas and Florida. French trading networks penetrated the continent along the waterways feeding the Gulf of Mexico,[95] renewing conflicts with both the British and the Spanish.[96] Trading networks established in the Mississippi River watershed, including the Ohio River valley, also brought the French into more contact with British trading networks and colonial settlements that crossed the Appalachian Mountains. Conflicting claims over that territory eventually led to war in 1754, when the French and Indian War broke out.[97]

Notes

- ↑ The first Indian War was King Philip's War, the second was King William's War, and the fourth was Father Rale's War. See Alan Taylor, Writing Early American History, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005, pg. 74.

- ↑ Denis Héroux, Robert Lahaise, Noë̈l Vallerand, "La Nouvelle-France", p.101

- 1 2 3 William Williamson. The history of the state of Maine. Vol. 2. 1832. p. 27; Griffiths, E. From Migrant to Acadian. McGill-Queen's University Press. 2005. p.61; Campbell, Gary. The Road to Canada: The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec. Goose Lane Editions and The New Brunswick Heritage Military Project. 2005. p. 21.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 405–407

- ↑ Stone, pp. 161, 165

- ↑ Craven, p. 288

- ↑ See e.g. the map in Winsor, p. 341, showing a 1687 map of the southeastern colonies

- ↑ Weber, pp. 100–107

- ↑ Cooper and Terrill, p. 22

- ↑ Weber, p. 158

- ↑ Crane, p. 385

- ↑ Waselkov and Hatley, p. 104

- ↑ Weber, pp. 158–159

- ↑ Arnade, p. 32

- ↑ Drake, p. 115

- ↑ Pope, pp. 202–203

- ↑ Drake, p. 115,203

- ↑ Drake, p. 36

- ↑ Drake, p. 150

- ↑ Newman, pp. 87,109–124

- ↑ Bryce, p. 58

- ↑ Newman, pp. 127–128

- ↑ Shurtleff, p. 492; MacVicar, p. 45; Arnade, p. 32; Prowse, pp. 211,223

- ↑ Leckie, p. 231

- 1 2 Peckham, p. 26

- ↑ Prowse, p. 223

- ↑ Peckham, p. 27

- ↑ Wright, p. 65

- ↑ Peckham, p. 58

- ↑ Waselkov and Hatley, pp. 105–137

- ↑ Crane, p. 382

- ↑ Crane, p. 380

- ↑ Oatis, pp. 49–50

- 1 2 Arnade, p. 33

- ↑ Winsor, p. 318

- ↑ Winsor, p. 319

- ↑ Arnade, pp. 35–36

- 1 2 Covington, p. 340

- ↑ Arnade, p. 36

- ↑ Crane, p. 390

- ↑ Higginbotham, pp. 308–312,383–385

- ↑ Peckham, p. 62

- 1 2 Peckham, p. 64

- ↑ Drake, p. 202

- ↑ Charland, Thomas (1979) [1969]. "Rale, Sébastien". In Hayne, David. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Peckham, p. 65

- ↑ See e.g. Drake, pp. 286–287

- ↑ Peckham, p. 67

- ↑ Drake, pp. 238–247

- ↑ Eccles, p. 139

- 1 2 3 Peckham, p. 71

- ↑ Parkman (1892), p. 184

- ↑ Drake. The Border Wars of New England. pp. 264–266

- 1 2 Peckham, p. 84

- ↑ Parkman (1892), pp. 8–14

- ↑ Parkman (1892), p. 14

- ↑ Peckham, p. 69

- ↑ Peckham, p. 70

- ↑ Rodger, p. 129

- ↑ Peckham, p. 72

- ↑ Drake, p. 281

- ↑ Eccles, p. 136

- ↑ Prowse, pp. 277–280

- ↑ Prowse, pp. 223, 276

- ↑ Prowse, p. 229

- ↑ Prowse, p. 235

- ↑ Prowse, pp. 242–246

- ↑ Prowse, pp. 246–248

- ↑ Prowse, p. 249

- ↑ Prowse, pp. 235–236

- 1 2 Peckham, p. 74

- ↑ Marshall, p. 1155

- ↑ Prowse, p. 258

- ↑ Morrison, pp. 161–162

- ↑ Morrison, pp. 162–163

- ↑ Calloway, pp. 107-110

- ↑ Reid, pp. 97–98

- ↑ Weber, pp. 144–145

- ↑ Weber, p. 199

- ↑ Weber, p. 166

- ↑ Weber, p. 180

- ↑ Peckham, p. 75

- ↑ Craven, pp. 301–302

- 1 2 Craven, pp. 307–309

- ↑ Prowse, p. 282

- ↑ Prowse, p. 251

- ↑ Prowse, p. 274

- ↑ Prowse, p. 277

- ↑ Plank, pp. 57–61

- ↑ Griffiths, p. 286

- ↑ Plank, pp. 71–79

- ↑ Griffiths, pp. 267–281, 393

- ↑ Griffiths, pp. 390–393

- ↑ See e.g. Parkman (1897) for the later history of British-Acadian conflict.

- ↑ Weber, p. 184

- ↑ Peckham, p. 82

- ↑ Parkman (1897), pp. 133–150

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Queen Anne's War. |

| Library resources about Queen Anne's War |

- Arnade, Charles W (1962). "The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700–1706". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 41 (1, July): 29–37. JSTOR 30139893.

- Bryce, George (1900). The Remarkable History of the Hudson's Bay Company. London: S. Low, Marston & Co. OCLC 11092807.

- Calloway, Colin (1991). Dawnland Encounters: Indians and Europeans in Northern New England. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. ISBN 9780874515268. OCLC 21873281.

- Cooper, William James; Terill, Tom E (1999). The American South: A History, Volume 1. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-6094-9. OCLC 227328018.

- Covington, James (1968). "Migration of the Seminoles into Florida, 1700–1820". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 46 (4, April): 340–357. JSTOR 30147280.

- Crane, Verner W (1919). "The Southern Frontier in Queen Anne's War". The American Historical Review. 24 (3, April): 379–395. doi:10.1086/ahr/24.3.379. JSTOR 1835775.

- Craven, Wesley Frank (1968). The Colonies in Transition: 1660–1713. New York: Harper & Row. OCLC 423532.

- Drake, Samuel Adams (1910) [1897]. The Border Wars of New England. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. OCLC 2358736.

- Eccles, William J (1983). The Canadian Frontier, 1534–1760. Albuquerque, NM: UNM Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0706-4. OCLC 239773206.

- Griffiths, Naomi Elizabeth Saundaus (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: a North American Border People, 1604–1755. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0. OCLC 180773040.

- Higginbotham, Jay (1991) [1977]. Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane, 1702–1711. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0528-4. OCLC 22732070.

- Leckie, Robert (1999). A Few Acres of Snow: the Saga of the French and Indian Wars. New York: John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-24690-9. OCLC 39739622.

- MacVicar, William (1897). A Short History of Annapolis Royal: the Port Royal of the French, From its Settlement in 1604 to the Withdrawal of the British Troops in 1854. Toronto: Copp, Clark. OCLC 6408962.

- Marshall, Bill; Johnston, Christina (2005). France and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. Oxford: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-85109-411-0. OCLC 264795152.

- Morrison, Kenneth (1984). The Embattled Northeast: the Elusive Ideal of Alliance in Abenaki-Euramerican Relations. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05126-3. OCLC 10072696.

- Newman, Peter C (1985). Company of Adventurers: The Story of the Hudson's Bay Company. Markham, ON: Viking. ISBN 0-670-80379-0. OCLC 12818660.

- Oatis, Steven J (2004). A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680–1730. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3575-5. OCLC 470278803.

- Parkman, Francis (1892). A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 767873.

- Parkman, Francis (1897). Montcalm and Wolfe: France and England in North America, Volume 1. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 7850560.

- Peckham, Howard (1964). The Colonial Wars, 1689–1762. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 1175484.

- Plank, Geoffrey (2001). An Unsettled Conquest. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1869-5. OCLC 424128960.

- Pope, Peter Edward (2004). Fish Into Wine: The Newfoundland Plantation in the Seventeenth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2910-3. OCLC 470480894.

- Prowse, Daniel Woodley (1896). A History of Newfoundland: from the English, Colonial, and Foreign Records. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. OCLC 3720917.

- Reid, John; Basque, Maurice; Mancke, Elizabeth; Moody, Barry; Plank, Geoffrey; Wicken, William (2004). The 'Conquest' of Acadia, 1710: Imperial, Colonial, and Aboriginal Constructions. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3755-8. OCLC 249082697.

- Rodger, N. A. M (2005). The Command of the Ocean: a Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815, Volume 2. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06050-8. OCLC 186575899.

- Shurtleff, Nathaniel Bradstreet (1871). A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston. Boston: Boston City Council. OCLC 4422090.

- Stone, Norman (ed) (1989). The Times Atlas of World History (Third ed.). Maplewood, NJ: Hammond. pp. 161, 165. ISBN 0-7230-0304-1.

- Thomas, Alan Clapp (1913). A History of England. Boston: D. C. Heath. OCLC 9287320.

- Waselkov, Gregory A; Hatley, M. Thomas (2006). Powhatan's Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9861-3. OCLC 266703190.

- Weber, David. The Spanish Frontier in North America. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05917-5.

- Winsor, Justin (1887). Narrative and Critical History of America, Volume 5. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 3523208.

- Wright, J. Leitch, Jr (1971). Anglo-Spanish Rivalry in North America. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-0305-5. OCLC 213106.