Treaty of Ryswick

| Treaty of Peace between France and Spain Treaty of Peace between France and England[lower-alpha 1] Suspension of Armed Conflict in Germany between France and the Holy Roman Empire Treaty of Peace and Commerce between France and the Dutch Republic Separate Article for the Dutch Republic Treaty of Peace between France and the Holy Roman Empire | |

|---|---|

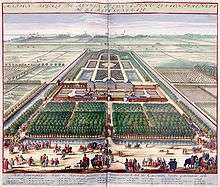

Huis ter Nieuwburg, location for the negotiations | |

| Context | End of the 1689-1697 Nine Years War |

| Signed | 20 September 1697 |

| Location | Rijswijk |

| Parties | |

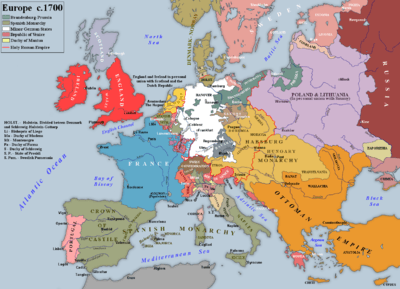

The Treaty or Peace of Ryswick, also known as The Peace of Rijswijk was a series of agreements signed in the Dutch city of Rijswijk between 20 September and 30 October 1697, ending the 1689-97 Nine Years War between France and the Grand Alliance of England, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and the Dutch Republic.[lower-alpha 2]

Background

The Nine Years War had been financially crippling for its participants, primarily because armies increased in size from an average of 25,000 in 1648 to over 100,000 by 1697.[lower-alpha 3] This was unsustainable for pre-industrial economies; military spending in this period absorbed 80% of English government revenues, with one in seven adult males serving in the army or navy, with similar figures were similar for other combatants.[1]

All sides were eager to end the war but finding a way of doing so proved difficult. Louis XIV sought to divide the Grand Alliance by persuading individual members to agree a separate peace, a tactic that had previously proved very successful. In 1693, French diplomats initiated informal talks with the Duchy of Savoy and the Dutch Republic.[2]

In August 1696, Savoy left the Alliance and signed the Treaty of Turin with France while the Convention of Vigevano of 7 October declared a general truce in Italy.[lower-alpha 4] Louis now agreed to restore Luxembourg to Spain and recognise William as King, clearing the way to finalise terms.[3] Formal negotiations were held in the Huis ter Nieuwburg at Ryswick, mediated by Swedish diplomat and soldier Niels Eosander, Baron of Lilliënrot.

By 1696, it was clear Charles II of Spain would die childless while his health was in terminal decline. Although no longer the dominant global power, the Spanish Empire remained powerful and largely intact, with territories in Italy, the Spanish Netherlands, the Philippines and large areas of the Americas.[4] The nearest claimants were from the Austrian Hapsburg and French Bourbon families, making the question of Charles' successor hugely significant.

Emperor Leopold wanted this issue addressed in the Peace; without it, he would only agree a ceasefire and he persuaded the Spanish to support him.[lower-alpha 5] In response, William and Louis appointed the Earl of Portland and Marshal Boufflers as their personal representatives; they met privately outside Brussels in June 1697 and quickly finalised terms, at which point Spain also agreed.[5] However, with the issue of Charles' successor unresolved, all sides accepted the likelihood of another war and began preparing for it.

Provisions

One of the most important issues was control of the French-occupied Spanish Duchy of Luxemburg, then considerably larger than it is today and essential to Dutch border security. Others were Strasbourg, strategic key to French possessions in Alsace-Lorraine and French recognition of William III as monarch of England and Scotland, rather than James II.[6]

During negotiations, the enormous financial costs of the war and military stalemate in Europe meant an increased focus on commercial issues and the colonial periphery. In early 1697, a French fleet arrived in the Caribbean, threatening the annual Spanish treasure fleet and British possessions like Jamaica.[7] In North America, or King William's War, Britain took Nova Scotia but under Count Frontenac, the French repulsed attacks on Quebec, captured York Factory and caused substantial damage to the New England economy.[8]

The final agreement restored the position to that of the 1679 Treaty of Nijmegen; France kept Strasbourg but returned Freiburg, Breisach, Philippsburg and the Duchy of Lorraine to the Holy Roman Empire. The French evacuated Catalonia, the Duchy of Luxembourg, Mons and Kortrijk in the Spanish Netherlands, while the Dutch placed garrisons in Namur and Ypres. Louis recognised William as King, withdrew support from James and abandoned claims to the Electorate of Cologne and the Electoral Palatinate. In North America, British and French positions were returned to pre-war boundaries, while Spain ceded Tortuga and Saint-Domingue to France, while the Dutch handed back Pondichéry in India.

The Peace consisted of a number of separate agreements; on 20 September 1697, France signed Treaties of Peace with Spain and England, a Ceasefire with the Holy Roman Empire and on 21 September a Treaty of Peace and Commerce with the Dutch Republic. [9] It also confirmed the provisions of the Treaty of Turin, although technically these were not part of the Peace.[10]

At this point, Charles II of Spain fell seriously ill, making Leopold reluctant to sign; one frustrated negotiator stated that 'it would be a shorter way to knock him on the head downright, rather than all Europe be kept in suspense.'[11] On 9 October, the Dutch signed an additional Article agreeing to leave the Alliance if Leopold did not also sign a Peace Treaty before 1 November; Charles now rallied once more and he reluctantly did so on 30 October.

Aftermath

The Nine Years War had shown France needed allies and Louis adopted a dual-track approach of a diplomatic offensive to seek support while keeping the French army on a war footing.[lower-alpha 6] Louis was concerned by the increase in Hapsburg power and confidence following victories over the Ottomans at Vienna in 1683 and Zenta in September 1697; however, the growing independence of German states like Bavaria also provided opportunities.

For Britain, France's acceptance of the 1688 Glorious Revolution marked a turning point in its rise as a global power. English mercantile interests had largely focused on the Levant trade but now began to challenge Spanish and Portuguese dominance of the Americas. However, the Tory majority in Parliament was determined to reduce costs and by 1699, the English military had been cut to less than 7,000 men.[12] This seriously undermined William's ability to negotiate on equal terms with France and despite his intense mistrust, he co-operated with Louis in an attempt to agree a diplomatic solution to the Succession. The Partition Treaties of The Hague (1698) and London (1700) ultimately failed to prevent the outbreak of war in 1702 but this was arguably the result of Louis' miscalculations.[13]

The Dutch Republic ended the Nine Years War with huge debts, forcing them to reduce expenditure on the navy and further weakening their economy. This and the huge additional investment required to win the 1701-1714 War of the Spanish Succession would bring the Dutch Golden Age to an end.[14]

Notes

- ↑ Until 1707, England and Scotland were separate countries under one monarch ie William but Treaties were signed by the King of Great Britain.

- ↑ The Duchy of Savoy joined the Grand Alliance in 1690 but agreed a separate peace with France in August 1696 and was not represented at Ryswick.

- ↑ Per historian John Childs, this reduced to 35,000 during the 1701-1714 War of the Spanish Succession.

- ↑ Full title Treaty between the Emperor and Spain and Savoy (and France) for a Suspension of Arms in Italy, signed at Vigevano, 7 October 1696

- ↑ In the 1689 Treaty of the Grand Alliance, England and the Dutch Republic had agreed to support Leopold's claim to the Spanish throne.

- ↑ The usual practice of the time was to disband them as quickly as possible.

References

- ↑ Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0719089964.

- ↑ Frey, Linda (ed), Frey, Marsha (ed) (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. Greenwood. pp. 389–390. ISBN 0313278849.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788. Manchester University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Storrs, Christopher (2006). The Resilience of the Spanish Monarchy 1665-1700. OUP Oxford. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0199246378.

- ↑ Frey, Linda (ed), Frey, Marsha (ed) (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 389. ISBN 0313278849.

- ↑ Morgan, WT (1931). "Economic Aspects of the Negotiations at Ryswick". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 14: 228. doi:10.2307/3678514.

- ↑ Morgan, WT (1931). "Economic Aspects of the Negotiations at Ryswick". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 14: 243. doi:10.2307/3678514.

- ↑ Grenier, John. "King William's War; New England's Mournful Decade". Historynet. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ Full text (1967). Major Peace Treaties of Modern History, 1648-1967 Volume I (2001 ed.). Chelsea House Publications. pp. 145–176. ISBN 0791066606.

- ↑ "The acts and negotiations, together with the particular articles at large of the general peace, concluded at Ryswick, by the most illustrious confederates with the French king to which is premised, the negotiations and articles of the peace, concluded at Turin, between the same prince and the Duke of Savoy". Early English Books; Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ↑ Morgan, WT (1931). "Economic Aspects of the Negotiations at Ryswick". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 14: 241. doi:10.2307/3678514.

- ↑ Gregg, Edward (1980). Queen Anne (Revised) (The English Monarchs Series) (2001 ed.). Yale University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0300090242.

- ↑ Falkner, James (2015). The War of the Spanish Succession 1701-1714 (Kindle ed.). 96: Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473872905.

- ↑ Meerts, Paul Willem (2014). Diplomatic negotiation: Essence and Evolution. http://hdl.handle.net/1887/29596: Leiden University dissertation. pp. 168–169.

Sources

- Childs, John; The Nine Years' War and the British Army (Manchester University Press, 1991);

- Durant, Will and Ariel; The Age of Louis XIV (Story of Civilization) (TBS Publishing, 1963);

- Eccles, William J; Canada under Louis XIV (Macmillan and Stewart, 1964);

- Frey, Linda (ed), Frey, Marsha (ed); The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. (Greenwood, 1995);

- Laramie, Michael; King William's War (Pen and Sword, 2018);

- Mowat, R. B. History of European Diplomacy, 1451–1789 (1928) 324 pages online pp 141-54.

- Thomson, Mark A; Louis XIV and William III, 1689-1697 (The English Historical Review, Volume 76, January, 1961 https://www.jstor.org/stable/557057)

See also

- Needle of Rijswijk

- Peace of Basel 1795 — Hispaniola

- Barrier Treaty

- Treaty of Utrecht (1713)