Invasion of Jamaica

| Invasion of Jamaica | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War (1654–60) | |||||||||

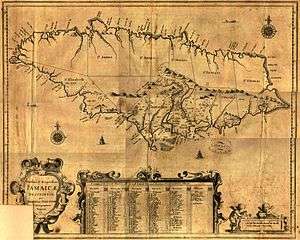

17th century map of Jamaica | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 1,500 settlers[1] |

7,000 troops 30 ships[2] | ||||||||

The Invasion of Jamaica was an amphibious expedition conducted by the English in the Caribbean in 1655 that resulted in the capture of the island from Spain. Jamaica's capture was the casus belli that resulted in actual war between England and Spain in 1655.[3] For the next period of the island's history, it was known as the Colony of Jamaica.

Background

In 1655 Cromwellian England joined France in its war with Spain. On the continent, an English contingent aided Marshal Turenne in defeating the Spanish at the Battle of the Dunes. But it was on the seas and in the colonies that the English Commonwealth directed its major effort against Spain. On March 31, 1655, Admiral William Penn sailed from Barbados in the West Indies with a fleet of 17 warships and 20 transports carrying 325 cannon, 1,145 seamen, and 1,830 soldiers. Reinforced by contingents from other English West Indian colonies to 8,000 strong, Penn was able to land 4,000 men under General Robert Venables near Santo Domingo on April 13.

The English forces suffered continuous setbacks at the hands of negroes and mulattoes during their march to Santo Domingo.[4] They suffered from Spanish artillery bombardment throughout the night of 25 April and into the next morning.[5] The foray was disastrous for the English as the troops were routed and driven back to their ships.

After its failure at Santo Domingo, the English expedition under Penn and Venables faced the prospect of returning in defeat to Oliver Cromwell. So the English leaders decided to attempt to capture Jamaica. The island had few defences—the Spanish settlers by this time numbered just over 1,500 men, women, and children. Penn, the English naval commander, had lost his faith in the officers of the accompanying army units after the siege of Santo Domingo, and assumed overall command of the English force.

Invasion

On Wednesday morning, being the 9th of May, we saw Jamaica Iand, very high land afar off. Wednesday the 10th our souldiers in numbers 7000 (the sea regiment being none of them) landed at the 3 forts...[6]

— From the letter of a soldier involved in England's 1655 invasion of Jamaica

On 19 May two Spanish settlers saw a huge fleet just as it rounded Point Morant and warned the Spanish Governor Juan Ramírez de Arellano. The islanders and the governor were caught completely off guard and had to man what fortifications they could. At dawn on 21 May the English penetrated the shallows of Caguaya Bay (now Cagway Bay) William Penn transferred from his 60 gun ship Swiftsure aboard a lighter 12 gun galley Martin and led a flotilla of smaller craft. The smaller craft were used because the bay was exceptionally shallow; some of the flotilla, including the Martin, grounded briefly before moving on. Soon, an exchange of shots began between the English and a battery covering the inner anchorage. A small number of inexperienced defenders was led by Francisco de Proenza, a local hacendado (estate owner), but they soon gave up the attack.

Penn then disembarked his contingent and advanced six miles to Santiago de la Vega, which he easily overran. Penn then occupied the town and obliged the defeated Ramirez to a request a parlay. Venables, despite being sick, came ashore on 25 May to dictate terms. He announced to Ramírez that the island was to be permanently annexed by the Commonwealth of England, and that the inhabitants are to abandon the island within a fortnight, on pain of death. Ramírez temporized for two days but eventually signed the arrangement on 27 May; shortly thereafter, he sailed for Campeche, dying en route.

Not all the Spanish residents recognized this arrangement, however. After evacuating many noncombatants from northern Jamaica to Cuba, Maestre de Campo de Proenza established his headquarters at the inland town of Guatibacoa. There he allied with the maroons of the mountainous interior to inaugurate a guerrilla war against English occupation.

Aftermath

The English were soon falling sick and starving and Penn and Venables would take most of the expedition back to England in August. Justifying Penn's and Venables fears for not capturing Hispaniola, Cromwell threw them both in the Tower.[7] The remaining English suffered severely from disease and want of provisions, dying by the hundreds. Within a year the 7,000 English officers and troops that took part in the invasion were reduced to 2,500.

Sickness soon swept through the Spanish resisters as well. One of the first victims was the unfortunate de Proenza, who was left blind. He was succeeded by Cristóbal Arnaldo de Issasi, who continued the largely ineffectual resistance for three more years.

When the English invaded, the Spanish freed their slaves, who fled into the mountainous forests of the interior, where they established free and independent communities, and fought a guerrilla war against the English. The Spanish attempted to retake Jamaica twice over the next few years, and to this end Issasi relied on his alliance with the Spanish Maroons to secure this victory.[8] The first attempt ended when Issasi was defeated at Ocho Rios in 1657. A much larger force was then recruited from New Spain, but was defeated at Rio Nuevo in 1658. However, Governor Edward D'Oyley succeeded in persuading one of the leaders of the Spanish Maroons, Juan de Bolas, to switch sides and join the English along with his Maroon warriors. In 1660, when Issasi realised that de Bolas had joined the English, he admitted that the Spanish no longer had a chance of recapturing the island, since de Bolas and his men knew the mountainous interior better than the Spanish and the English. Issasi gave up on his dreams, and fled to Cuba.[9][10]

After these failures, Spain eventually ceded Jamaica and the Cayman islands to the English crown at the Treaty of Madrid (1670).

Under British rule, Jamaica soon became a hugely profitable possession, producing large quantities of sugar for the home market and eventually for other colonies.

References

- ↑ Marly pg. 149

- ↑ Marly pg. 149

- ↑ Hart p.44.

- ↑ Nichols, Patrick John (2015). ""Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670".

- ↑ Harrington, Matthew Craig (2004). ""The Worke Wee May Doe in the World" the Western Design and the Anglo-Spanish Struggle for the Caribbean, 1654–1655". Florida State University.

- ↑ Venables, Robert (1900). Firth, C. H., ed. The Narrative of General Venables. Longmans, Green, and Co.

- ↑ Rodger pp. 23 - 24.

- ↑ Mavis Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica 1655-1796: a History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal (Massachusetts: Bergin & Garvey, 1988), pp. 14-17.

- ↑ Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica 1655-1796, pp. 17-20.

- ↑ C.V. Black, History of Jamaica (London: Collins, 1975), p. 54.

- Bibliography

- Black, Clinton, The story of Jamaica from prehistory to the present. Collins, London 1965.

- Hart, Francis Russel. Admirals of the Caribbean, Boston, 1922.

- Marly, David Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492-1997 ABC-CLIO Ltd 1998 ISBN 0-87436-837-5

- Rodger, N. A. M.. The Command of the Ocean, New York, 2005. ISBN 0-393-06050-0

- Pestana, Carla Gardina The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire, Harvard University Press, 2017. ISBN 9780674737310