Acre (state)

| State of Acre | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | |||

| |||

Location of the State of Acre in Brazil | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Capital | Rio Branco | ||

| Government | |||

| • Governor | Tião Viana (PT) | ||

| • Vice Governor | Nazareth Lambert (PT) | ||

| • Senators |

Gladson Cameli (PP) Jorge Viana (PT) Sérgio Petecão (PSD) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 152,581 km2 (58,912 sq mi) | ||

| Area rank | 16th | ||

| Population (2012)[1] | |||

| • Total | 758,786 | ||

| • Rank | 25th | ||

| • Density | 5.0/km2 (13/sq mi) | ||

| • Density rank | 23rd | ||

| Demonym(s) | Acreano | ||

| GDP | |||

| • Year | 2006 estimate | ||

| • Total | R$ 4,835,000,000 (26th) | ||

| • Per capita | R$ 7,041 (18th) | ||

| HDI | |||

| • Year | 2014 | ||

| • Category | 0.719 – high (15th) | ||

| Time zone | UTC–5 (BRT–2) | ||

| Postal Code | 69900-000 to 69999-000 | ||

| ISO 3166 code | BR-AC | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Acre (Brazilian Portuguese: [ˈakɾi])[2] is a state located in the northern region of Brazil. Located in the westernmost part of the country with a two hours time difference from Brasília, Acre is bordered clockwise by Amazonas to the north and northeast, Rondônia to the east, the Bolivian department of Pando to the southeast, and the Peruvian regions of Madre de Dios, Ucayali and Loreto to the south and west. It occupies an area of 152,581.4 km2, being slightly smaller than Tunisia.

Its capital and largest city is Rio Branco. Other important places include Cruzeiro do Sul, Sena Madureira, Tarauacá and Feijó.

The intense extractive activity, which reached its height in the 20th century, attracted Brazilians from many regions to the state. From the mixture of sulista, Southeast Brazil, nordestino, and indigenous traditions arose a diverse cuisine, which unites sun-dried meat (carne-de-sol) with pirarucu, a typical fish of the region. Such dishes are seasoned with tucupi, a sauce made from manioc.

Fluvial transport, concentrated on the Juruá and Moa rivers, in the western part of the state, and the Tarauacá and Envira Rivers in the northwest, is the principal form of circulation, especially between November and June, when the rain leaves the BR-364 impassable, which connects Rio Branco to Cruzeiro do Sul.

Etymology

The name, which passed from the river to the territory in 1904, and to the state in 1962, perhaps originates from the Tupi word a'kir ü "green river" or from the form a'kir, of the tupi word ker, "to sleep, to rest"; but it is almost certain to be a deformation of Aquiri, the spelling which explorers of the region utilized to express Umákürü, or Uakiry, a term from the Ipurinã dialect. There is also a hypothesis that Acquiri derives from Yasi'ri, or Ysi'ri, meaning "flowing or swift water".

On the voyage which he made on the Purús River in 1878, the colonizer, João Gabriel de Carvalho Melo, wrote from there to the merchant, Viscount of Santo Elias (from Pará), asking him for goods to be sent to the "mouth of the Aquiri River". Since in Belém the proprietor of the commercial establishment and the employees were not able to understand João Gabriel's handwriting, or because he had hastily written Acri or Aqri, instead of Aquiri, the goods and the invoice arrived to the colonizer as having been sent to the Acre River.

Acre possesses some nicknames: the End of Brazil, The Rubber Tree State, the Latex State and the Western End.

The native inhabitants of Acre are called acrianos, in the singular acriano. Until the entry in force of the Orthographic Agreement of 1990, the correct spelling was acreano in the singular and in the plural acreanos. In 2009, with the new orthographic agreement, the change generated controversy between the Academy of Letters of Acre (Academia Acreana de Letras) and the Brazilian Academy of Letters (Academia Brasileira de Letras), alleging that the change would mean the denial of the state's historical and cultural roots, changing the last letter of the toponym from "E" to "I".

Geography

The state of Acre occupies an area of 152,581 km2 (58,911 mi2) in the extreme west of Brazil. It is located at 70º00'00" west longitude from the Prime Meridian and at 09º00'00" latitude south of the equator. In Brazil, the state is part of the North Region, forming borders with the states of Amazonas and Rondônia, and with two countries: Peru and Bolivia.

Practically all of the terrain of the state of Acre is part of the low sandstone plateau, or terra firme, morphological unit which dominates most of the Brazilian Amazon. These terranes rise, in Acre, from the southeast to the northeast, with very tabular topography in general. In the extreme west is found the Serra da Contamana or Serra do Divisor, along the western border, with the highest altitudes in the state (609 m; 1,998 ft). About 63% of state's surface is lies between 200 and 300 m (660 and 980 ft) in height; 16% between 300 and 609 (984 and 1,998 ft); and 21% between 200 and 135 (656 and 443 ft).

The climate is hot and very humid, of the Am type in the Köppen climate classification system, and the monthly average temperatures vary between 24 and 27 °C (75 and 81 °F), being the lowest average of the North Region. The rainfall reaches an annual total of 2,100 mm (83 in), with a clear dry season in the months of June, July, and August. The Amazon Rainforest covers all of the state territory. Very rich in rubber trees of the most valuable species (Hevea brasiliensis) and Brazil nut trees (Bertholletia excelsa), the forest guarantees that Acre is the greatest national producer of rubber and nuts. Acre's principal rivers, mostly navigable during the wet season (the Juruá, Tarauacá, Envira, Purús, Iaco, and Acre), cross the state with almost parallel courses which will only converge outside of its territory.

Vegetation

The Amazon represents over half of the planet's remaining rainforests and comprises the largest and most species-rich tract of tropical rainforest in the world. Wet tropical forests are the most species-rich biome, and tropical forests in the Americas are consistently more species-rich than the wet forests in Africa and Asia.[3] As the largest tract of tropical rainforest in the Americas, the Amazonian rainforests have unparalleled biodiversity. More than 1/3 of all species in the world live in the Amazon Rainforest.[4]

History

.jpg)

.jpg)

The region of present-day Acre is thought to have been inhabited by Pre-Columbian civilizations since at least 2,100 years ago. Evidence includes complex geoglyphs of this age found in the area, which also suggest that the natives who crafted them had a relatively advanced knowledge on this technology. Since at least the early 15th century, the region has been inhabited by peoples who spoke Panoan languages; their territory was geographically close to the Incas.

In the mid-18th century, the region was colonized by the Spanish and became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Following the Peruvian and Bolivian wars of independence, which ended in 1826, the region and large portions around it became part of Bolivia. It was a territory of the short-lived Peru–Bolivian Confederation (1836–1839), until the two countries separated again and the region returned to Bolivian control.

The discovery of rubber tree groves in the region in the mid-19th century attracted more immigration, and this included particularly Brazilian exploiters. Despite the increased numbers of Brazilians, the Treaty of Ayacucho (1867), determined that the region belonged to Bolivia. By 1877, Acre's population was almost entirely Brazilians coming from the Northeast.

In 1899, Brazilian settlers from Acre created an independent state in the region called the Republic of Acre. Bolivians tried to gain control of the area, but Brazilians revolted and there were border confrontations, generating the episode which became known as the Acre War. On November 17, 1903, with the signing over and sale in the Treaty of Petrópolis, Brazil received final possession of the region. Acre was then integrated into Brazil as a territory divided into three departments. The territory passed under Brazilian sovereignty in exchange for the payment of two million pounds sterling, land taken from Mato Grosso and in accordance with the construction of the Madeira-Mamoré railway.

Having been united in 1920, on June 15, 1962, it was elevated to the category of state, being the first to be governed by a woman, the teacher Iolanda Fleming.

During the Second World War, the rubber tree groves of Malaya were taken by the Japanese, and Acre thus left a great mark on western and world history, helping to change the course of the war in favour of the allies. This was thanks to the Rubber Soldiers, natives mostly of the Ceará plantation. It was perhaps due to Acre and its decisive contribution to the allied victory, that Brazil received North American resources to form the National Steel Company (Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional), and thus aid in the industrialization of the Central-south, which was until such time mostly stagnant, and which did not yet possess basic heavy industries.

On April 4, 2008, Acre won a judicial debate with the state of Amazonas in relation to the dispute surrounding the Cunha Gomes Line, which culminated in the annexation of part of the municipalities of Envira, Guajará, Boca do Acre, Pauini, Eirunepé and Ipixuna. The territorial redefinition consolidated the incorporation of 1.2 million hectares of the Liberdade, Gregório, and Mogno forest complex to the territory of Acre, which corresponds to 11,583.87 km2.

Initial settlement

Since the 1970s, numerous geoglyphs have been discovered on deforested land in Acre dating between 0–1250 AD, leading to claims about Pre-Columbian civilizations.[5][6] The BBC's Unnatural Histories claimed that the Amazon rainforest, rather than being a pristine wilderness, has been shaped by man for at least 11,000 years through practices such as forest gardening.[7] Ondemar Dias is accredited with first discovering the geoglyphs in 1977 and Alceu Ranzi with furthering their discovery after flying over Acre.[7][8]

During the 17th century, Portuguese penetrations had already reached many of the maximum ends of Brazil. The expansion of the geographic horizon to the west was an inevitable consequence, reaching lands of Spanish possession; a fact which became a topic of the Treaties of Madrid (1750) and San Ildefonso[9] (1777). Both of the treaties, based on the explorations of Portuguese bandeirante Manoel Félix de Lima of the Guaporé and Madeira River drainage basins, established the riverbeds of the Mamoré and Guaporé to their maximum western limits on the left bank of the Javari as a dividing line between the respective areas in question.

The settlement of the zone, stimulated by the creation of the new royal captaincy of Mato Grosso (1751), occurred in the direction of the frontier, causing several important centers to emerge: Vila Bela (1752)[10] on the banks of the Guaporé, Vila Maria (1778)[11] on the Paraguay River, and Casalvasco (1783).[12] Until the mid-19th century, a systematic settling of the area was not thought of. At that time, the great virgin source of rubber found there would attract commercial interest, provoking its colonization.

The economic politics of the empire, directed towards agricultural exportation activities based on coffee, did not permit the utilization and incorporation of the territories of the extreme west. From this negligence it happened that in Cândido Mendes de Almeida's Atlas of the Empire of Brazil (1868), a model of its time, the Acre River and its principal tributaries did not appear, being completely unknown to geographers.

Notwithstanding such politics, some few armed bands of Brazilian explorers exploited the rural and unpopulated region,[13] not knowing whether they pertained to Brazil, Peru, or Bolivia. Hence, still in the mid 19th century, fed by the drive which the search for rubber occasioned, solicited as it was on the international market, various expeditions searched out the area seeking to facilitate the installation of colonists. At that time, João Rodrigues Cametá initiated the conquest of the Purús River;[14] Manuel Urbano da Encarnação, an Indian with an extensive knowledge of the region, reached the Acre River, traveling up it as far as the vicinity of the Xapuri;[14] and João da Cunha Correia reached the drainage basin of the upper Tarauacá.[15] All this clearing took place, for the most part, on Bolivian land.

Exploitative activities, the industrial importance of the rubber reserves, and the penetration of Brazilian colonists in the region raised the attention of Bolivia, which solicited a better fixation of boundaries. After much failed negotiation, in 1867 the Treaty of Ayacucho was signed, which recognized the colonial uti possidetis.[16] A border was established parallel to the confluence of the Beni and Mamoré Rivers running eastward to the headwaters of the Javari River, even though the source of this river was not yet known.

Northeast Occupation

As the price of rubber rose in the market,[17] the demand for it grew, and the race to the Amazon increased. Plantations multiplied in this manner in the valleys of the Acre, Purús, and farther west, the Tarauacá: in one year (1873–1874), in the drainage basin of the Purús, the population rose from around one thousand to four thousand inhabitants. On the other hand, the imperial government, already sensitive to the resulting offerings of rubber, considered the entire valley of the Purús to be Brazilian.

Also, in the second half of the 19th century, disturbances were registered in the demographic and geo-economic balance of the empire, with the coffee boom in the south channeling financial resources and workers, in detriment to the northeast.[18] The growing impoverishment of that region stimulated migratory waves to the states of Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and São Paulo.[18] The movement of population became particularly active during the prolonged drought of the northeastern interior, from 1877 to 1880, expelling hundreds of Cearenses, who headed for the rubber plantations in search of work.[19]

The advance of Cearense migration proceeded to the banks of the Juruá[20] and accelerated the occupation of land which Bolivia would later reclaim. The great fluvial river beds and their tributary systems were then intensely trafficked by small ship fleets of varied transport, transporting colonists, goods, and supply material to the most isolated nuclei. The governments of Amazonas and Pará quickly instituted the establishment of supply houses, which financed various types of operations, guaranteed credit, and promoted the commercial incentive of the rubber tree groves.[21]

The rubber race assumed proportions similar to those of the search for gold veins in the 18th century.[22] The results were equal. The situation drew the attention of the government to the economic utilization of an almost completely unknown area, besides permitting -as in a colony- the patrimonial incorporation of new regions, on the basis of penetration movements by private enterprise.

Land dispute

In 1890, a Bolivian official, José Manuel Pando, alerted his government to the fact that in the drainage basin of the Juruá there were more than three hundred rubber plantations, with the occupation by Brazilians taking root more and more rapidly on Bolivian soil.[23] The Brazilian penetration had advanced in depth west from the 64th meridian to beyond the 72nd, in an extension of one thousand kilometers, even though the borders had already been fixed above the confluence of the Beni and Mamoré Rivers according to the Treaty of 1867.[24]

In 1895 a new commission for the settlement of demarcation was created.[22] The Brazilian representative, Gregório Taumaturgo de Azevedo, resigned after verifying that the ratification of the Treaty of 1867 would harm the rubber gatherers which were installed there.[25][26] In 1899, the Bolivians established an administrative post in Puerto Alonso, exacting taxes and customs duties upon Brazilian activities.[27] The following year, Brazil accepted the sovereignty of Bolivia in the zone, when it officially recognized the old boundaries at the confluence of the Beni and Mamoré.

The rubber gatherers, distant from the diplomatic process, judged their interests to have been cheated, and initiated insurrection movements. In the same year that Bolivia implanted administration in Puerto Alonso (1899), two serious contestations occurred.[27]

In April, a Cearense lawyer, José Carvalho, led an armed movement, which culminated in the expulsion of the Bolivian authorities.[22] Shortly thereafter, Bolivia began negotiations with an Anglo-American trust, the Bolivian Syndicate, in order to promote, with exceptional force (exacting of taxes, armed force), the political and economic incorporation of Acre into its territory.[22] The governor of Amazonas, Ramalho Júnior, informed of the agreement by a functionary of the Bolivian consulate in Belém, Luis Gálvez Rodríguez de Arias, sent military contingents forward to occupy Puerto Alonso.[22] Gálvez proclaimed the independence of Acre, in the form of a republic, becoming its president with the acquiescence of the rubber gatherers. Under protests from Bolivia, President Campos Sales abolished the ephemeral republic (March 1900).[22]

Bolivians, reinstated in the region, suffered, still in 1900, the assault of the so-called Floriano Peixoto expedition or "expedition of the poets",[28] thus called, for being constituted for the most part of intellectual bohemians from Manaus.[28] The conflict did not have great consequences, since, following brief fighting in the area surrounding Puerto Alonso, the expedition was completely scattered.[28]

Ultimately, the Bolivian government signed a contract with the Bolivian Syndicate (July 1901).[22] The Brazilian congress, shocked by the arbitrariness of the act, took measures, canceling commercial accords and navigation between the two countries, and suspending the right of travel to Bolivia.

At the same time, Brazilians organized an armed assault of great size on the conflicted area.[22] The operations were led by a former student of the Military School of Rio Grande do Sul (Escola Militar do Rio Grande do Sul), José Plácido de Castro. The rubber gatherers occupied the village of Xapuri in Alto Acre (August 1902), apprehending the Bolivian authorities.[22] Finally, Plácido de Castro's forces besieged Puerto Alonso, proclaiming the Independent State of Acre, after the capitulation of Bolivian troops (February 1903).[22]

Diplomatic intervention

To Plácido de Castro, proclaimed governor of the new Independent State of Acre,[29] it was left to discuss the question of borders in the diplomatic sphere.[30] The Baron of Rio Branco, who had just assumed the role of minister of foreign relations,[31] immediately opened channels which were meant to have put an end to the question.

The simplest problem, with the Bolivian Syndicate, was resolved by means of the compensation of one hundred ten thousand pounds to renounce the contract (February 1903).[32] Next, commercial relations were reestablished with Bolivia,[22] while a part of the territory on the upper Purús and Juruá, militarily occupied (March 1903) was declared litigious. From the subsequent talks, it followed that Bolivia would cede an area of 142,800 km2, in exchange for two million pounds sterling, paid in two installments.[22] Brazil committed to the construction of a Madeira-Mamoré Railway, connecting Porto Velho to Guajará-Mirim, at the confluence of the Beni and the Madeira.[22] Such were the principal stipulations of the Treaty of Petrópolis (November 17, 1903), through which Brazil acquired the future territory, now state of Acre.[22]

There remained the question of Peru, which also claimed sovereignty over the entire territory of Acre and part of the state of Amazonas, in light of colonial titles.[33] After armed conflicts between Brazilians and Peruvians on the upper Purús and Juruá, a joint administration was established in those regions (1904).[19] The studies for the fixation of borders proceeded until the end of 1909, when a treaty was signed which completed the political integration of Acre into Brazilian territory.

Development from territory to statehood

The evolution of Acre appears to be a typical phenomenon of modern penetration in the history of Brazil, accompanied by important contributions to the economic projection of the country. Exercising a prominent role in national exports until 1913,[34] when rubber was introduced to European and North American markets, Acre enjoyed a period of great prosperity: at the start of the 20th century, in a period of less than ten years, it boasted more than 50,000 inhabitants.

It may be asserted that all the endeavors towards the integration of Acre into Brazilian life correspond to the parallel efforts of the federal government, from 1946 on, to the effect of recuperating the economy of the Amazon, including it in regional development projects.

Attending to the judicial arrangements of the Treaty of Petrópolis, President Rodrigues Alves sanctioned the law which created the Territory of Acre (1904),[35] further dividing it into three departments: Alto Acre, Alto Purús, and Alto Juruá, the latter being separated to form Alto Tarauacá (1912). The departmental administration was exercised until 1921 by mayors appointed by the President of Brazil.[36] At that time the arrangements were altered, passing the administration to a governor. The second Constitution of Brazil (1934) conceded to Acre the right to elect representatives to the National Congress of Brazil.[37]

During the Estado Novo (New State) political ideas involving the valorization of the interior took hold, with the intention of promoting the articulation of more isolated areas. Thereafter, the vote of 1946 commended the channeling of budgetary resources from the Union to the Amazon, determining that the Territory of Acre would be elevated to the condition of state as soon as its revenue reached the equivalent of the lowest state tax exaction.[38]

In the 1960s, the second cycle of efforts to accelerate the progress of the Amazon area was begun with the Superintendency of the Development of the Amazon (Superintendência do Desenvolvimento da Amazônia or SUDAM, 1966).[39] Better networking of regional sub-sectors within the state was sought out, thus connecting the branch lines of the Transamazônica, which connected Rio Branco and Brasiléia, on the upper course of the Acre River, and Cruzeiro do Sul, on the banks of the Juruá, crossing the valleys of the Purús and the Tarauacá. Planning politics developed, therefore, destined to correct the demographic, economic, and political distortions of national integration.

Demographics

According to the IBGE of 2007, there were 664,000 people residing in the state. The population density was 4.5 inh./km2.

Urbanization: 69.6% (2006); Population growth: 3.3% (1991–2000); Houses: 162,000 (2006).[40]

The last PNAD (National Research for Sample of Domiciles) census revealed the following numbers: 441,000 Brown (Multiracial) people (66.5%), 172,000 White (26.0%), 45,000 Black (6.8%), 4,000 Asian or Amerindian people (0.7%).[41]

Indigenous population

Acre is inhabited by various indigenous groups of the Panoan language family, including Kashinawa, Jaminawa and Xanenawa. There are also three groups of other language families, Madiha (Kulina) of the Arawan family as well as Yine (Manchineri) and Ashaninka (Kampa) of the Arawakan family.

Largest cities

Largest cities or towns in Acre (state) (2010 census of Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística)[42] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Mesoregion | Pop. | Rank | Mesoregion | Pop. | ||||

Rio Branco  Cruzeiro do Sul |

1 | Rio Branco | Vale do Acre | 335,796 | 11 | Epitaciolândia | Vale do Acre | 15,126 |  Sena Madureira  Tarauacá |

| 2 | Cruzeiro do Sul | Vale do Juruá | 78,444 | 12 | Porto Acre | Vale do Acre | 14,806 | ||

| 3 | Sena Madureira | Vale do Acre | 37,993 | 13 | Rodrigues Alves | Vale do Juruá | 14,334 | ||

| 4 | Tarauacá | Vale do Juruá | 35,526 | 14 | Marechal Thaumaturgo | Vale do Juruá | 14,200 | ||

| 5 | Feijó | Vale do Juruá | 32,311 | 15 | Acrelândia | Vale do Acre | 12,538 | ||

| 6 | Brasiléia | Vale do Acre | 21,438 | 16 | Porto Walter | Vale do Juruá | 9,172 | ||

| 7 | Senador Guiomard | Vale do Acre | 20,153 | 17 | Capixaba, Acre | Vale do Acre | 8,810 | ||

| 8 | Plácido de Castro | Vale do Acre | 17,203 | 18 | Bujari | Vale do Acre | 8,474 | ||

| 9 | Xapuri | Vale do Acre | 16,016 | 19 | Manuel Urbano, Acre | Vale do Acre | 7,989 | ||

| 10 | Mâncio Lima | Vale do Juruá | 15,246 | 20 | Jordão | Vale do Juruá | 6,531 | ||

Economy

.jpg)

The service sector is the largest component of GDP at 66%, followed by the industrial sector at 28.1%. Agriculture represents 5.9%, of GDP (2004). Acre exports: wood 85.6%, poultry (chicken and wild turkey) 4.7%, wood products 1.7% (2002).

Share of the Brazilian economy: 0.2% (2005).

Education

Portuguese is the official national language, and thus the primary language taught in schools. English and Spanish are also part of the official high school curriculum.

Educational institutions

- Universidade Federal do Acre (Ufac) (Federal University of Acre);

- Faculdade da Amazônia Ocidental (Faao) (College of Western Amazon);

- Faculdade de Ciências Jurídicas e Sociais Applicadas Rio Branco (Firb);

- Instituto de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Vale do Juruá (Ieval);

- Instituto de Ensino Superior do Acre (Iesacre);

- União Educacional do Norte (Uninorte).

Infrastructure

International airport

Rio Branco International Airport is located in a rural zone of the municipality of Rio Branco, in the state of Acre. It was opened on November 2, 1999, with a unique characteristic: it moved 22 kilometers away from the previous airport site. Rio Branco Airport serves domestic and international flights (by scheduled carriers and air taxi firms) along with general and military aviation. The terminal can receive 270 thousand passengers a year and serves an average of 14 daily operations.

Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport is located 18 kilometers away from the city center, which helps access to the Alto Juruá region. It was opened on October 28, 1970, and absorbed by Infraero on March 31, 1980. The airport infrastructure was built in 1976 by the municipal government. In 1994 the runway was totally renovated.

Highways

- BR-364 (Rio Branco to Rondônia);

- BR-317 (Rio Branco to south of Acre);

- AC-040 (Rio Branco to Plácido de Castro);

- AC-401 (Plácido de Castro to Acrelândia);

- AC-010 (Rio Branco to Porto Acre).

Sports

Rio Branco provides visitors and residents with various sport activities.

Stadiums

- Arena da Floresta stadium;

- José de Melo stadium;

- Federação Acreana de Futebol stadium;

- Dom Giocondo Maria Grotti stadium;

- Adauto de Brito stadium;

- and many others.

The Arena da Floresta stadium in Rio Branco was one of the 18 candidates to host games in the 2014 FIFA World Cup, which was held in Brazil, but did not make it to the final 12 chosen.

Flag

The flag was adopted on March 15, 1921. It is a variation of the flags used by the secessionist state of Acre, with the yellow and green parts exchanged and mirrored. The yellow color symbolizes peace, green hope, and the star symbolizes the light which guided those who worked to make Acre a state of Brazil.

Statistical and legal subdivisions

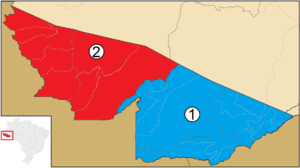

Acre is divided into twenty-two municipalities, five microregions and two mesoregions:

2 Mesoregion of Vale do Juruá

Vale do Acre

- Microregion of Brasileia

- Microregion of Rio Branco

- Microregion of Sena Madureira

Vale do Juruá

- Microregion of Cruzeiro do Sul

- Microregion of Tarauacá

References

- ↑

- ↑ The European Portuguese pronunciation is [ˈa.kɾɨ].

- ↑ Turner, I.M. 2001. The ecology of trees in the tropical rain forest. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-80183-4

- ↑ Amazon Rainforest, Amazon Plants, Amazon River Animals

- ↑ Simon Romero (January 14, 2012). "Once Hidden by Forest, Carvings in Land Attest to Amazon's Lost World". The New York Times.

- ↑ Martti Pärssinen, Denise Schaan and Alceu Ranzi (2009). "Pre-Columbian geometric earthworks in the upper Purús: a complex society in western Amazonia". Antiquity. 83 (322): 1084–1095.

- 1 2 "Unnatural Histories - Amazon". BBC Four.

- ↑ Junior, Gonçalo (October 2008). "Amazonia lost and found". Pesquisa (ed.220). FAPESP.

- ↑ Treaty of Madrid "Tratado de Madri"

- ↑ FERREIRA, João Carlos Vicente. "História da Vila Bela da Santíssima Trindade" Archived 2010-08-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Cáceres" BrasilViagem.com. Page visited on October 05, 2010

- ↑ "Fixação e consolidação da fronteira" Official Site of the Legislative Assembly of Mato Grosso. Page visited on October 05, 2010.

- ↑ Pertiñez, Dom Joaquín. "O Acvre, o Nordeste e os nordestinos" Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine.. Official site of the Diocese of Rio Branco. Page visited on October 05, 2010

- 1 2 SILVA, Hiram Reis and (July 7, 2009) "João Rodrigues Cametá" Archived 2011-07-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Tarauacá: Ontem, hoje e amanhã" Tarauacá.com. Page visited on October 05, 2010.

- ↑ "O Tratado de Madrid e o Tratado de Ayacucho" GrupoEscolar.com Page visited on October 6, 2010

- ↑ "A queda do Ciclo da Borracha". Official site of the Municipality of Porto Velho (October 27, 2006). Page visited on October 6, 2010

- 1 2 FURTADO, Celso. "A evolução da economia na República Velha". Marcilio.com. Page visited on October 06, 2010

- 1 2 TOSCANO, Fernando. "Estados Brasileiros: Acre" Portal Brasil. Page visited October 06, 2010

- ↑ "História de Ipixuna". Official site of the Public Library of Amazonas. Page visited on October 06, 2010.

- ↑ "As Casas Aviodoras" WEB High School. Page visited on October 06, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 GURGEL, Rodrigo. "Revolução Acreana: Bolívia e Brasil disputam o Acre". UOL Education. Page visited on October 06, 2010.

- ↑ ILVA CASTRO, Jamerson. "História das Bandeiras de Portugal e do Brasil Official site of the city councilman. Page visited on October 09, 2010

- ↑ "Tratado de Ayacucho" Wikisource in Portuguese (March 27, 1867). Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ ALBUQUERQUE, Kátya Fernandez. "A Questão do Acre" Official site of the Fluminense Society of Philologic and Linguistic Studies. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ SILVA, Hiram Reis e (June 20, 2009). "Tenente-Coronel Gregório Taumaturgo de Azevedo" Archived 2011-07-15 at the Wayback Machine. Roraima in Foucus. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- 1 2 "História de Porto Acre IBGE Library. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- 1 2 3 SCILLING, Voltaire. "A Expedição dos Poetas" Earth Education:History. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ "Plácido de Castro" UOL Education. Page visitetd on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ SILVA, Leo. "Plácido de Castro, Rio Branco e a Questão do Acre Official site of the Secretary of Education of the State of Rio de Janeiro. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ "José Maria da Silva Paranhos Junior". Official site of the Ministry of Foreign Relations of Brazil. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ FREITAS, Newton. "Nacionalização Boliviana". Official site of the author. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ "A História do Estado do Acre, região Norte do Brasil - fotos e dados que ilustram este tema". Hjobrasil.com. Page visited on October 9, 2010.

- ↑ "O Ciclo da Borracha". Suapesuisa.com. Pge visited on October 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Governador Binho Marques fará revista às tropas da PMAC". Official site of the State of Acre (May 24, 2007). Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ LOUREIRO, Antonio José Souto (2008). "Histórico do Grande Oriente do Amazonas". Official site of Masonry in Amazonas. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ ANDRADA, Antônio Carlos Ribeiro de (16 de julho de 1934). "Constituição da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil de 1934" Official site of the Presidency of the Federal Republic of Brazil.

- ↑ VIANA, Fernando de Mello (September 18, 1946). "Constituição da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil de 1946" Official site of the Presidency of the Federal Republic of Brazil. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ FRIGOLETTO DE MENEZES, Eduardo. "A Sudam – Superintendência do Desenvolvimento da Amazônia". Official site of the author. Page visited on October 09, 2010.

- ↑ Source: PNAD.

- ↑ Síntese de Indicadores Sociais 2007 (PDF) (in Portuguese). Acre, Brazil: IBGE. 2007. ISBN 85-240-3919-1. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ "estimativa de 2009 do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística". Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 30 March 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.