Sébastien Rale

Sébastien Racle (anglicized as Sebastian Rale or Râle, Rasle, Rasles (January 20, 1657 – August 23, 1724)) was a Jesuit missionary and lexicographer who worked among the eastern Abenaki people. He was stationed on the border of Acadia and New England, and encouraged Indian raids upon the Colonial settlements in Maine. He fought throughout King William's War and Queen Anne's War, and was eventually killed by the Colonists during Father Rale's War.[1]

Early years

Rale was born in Pontarlier, France and studied in Dijon. In 1675, he joined the Society of Jesus at Dole and taught Greek and rhetoric at Nîmes. He volunteered for the American missions in 1689 and came to the New World in a party led by Governor-general Louis de Buade de Frontenac of New France.[2] His first missionary work was at an Abenaki village in Saint Francois, near Quebec City. He then spent two years with the Illiniwek Indians at Kaskaskia.

Queen Anne's War

In 1694, Râle was sent to direct the Abenaki mission at Norridgewock, Maine on the Kennebec River. He made his headquarters at Norridgewock where he built a church in 1698.[1] The New England colonists were suspicious of a French missionary arriving in the midst of a tribe that was already hostile, anticipating that the Frenchman would do his best to stoke this hostility.[2]

Queen Anne's War pitted New France against New England, fighting to control the region. Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley arranged a conference with tribal representatives at Casco Bay in 1703 to propose that they remain neutral. However, a party of the Norridgewock tribe joined a larger force of French and Indians commanded by Alexandre Leneuf de Beaubassin to attack Wells, Maine in the Northeast Coast Campaign. The English suspected Father Rale of inciting the tribe against them; French minister Pontchartrain wrote to Rale's Jesuit superior because he suspected Rale of not showing enough enthusiasm about fanning the flames of war.[1]

Governor Dudley put a price on Rale's head. In the winter of 1705, 275 British soldiers were dispatched under the command of Colonel Winthrop Hilton to seize Rale. The priest was warned in time, however, and escaped into the woods with his papers, but the militia burned the village and church.[1] Rale wrote to his nephew:

It is needful to control the imagination of the savages, too easily distracted, I pass few working days without making them a short exhortation for the purpose of inspiring a horror of the vices to which their tendency is strongest, and for strengthening them in the practice of some virtue.… My advice always shapes their resolutions.

Rale also succeeded in attaching the tribe to the New France side of the war. The French induced in the Indians a deep distrust of English intentions—and they accomplished this despite Abenaki dependence on English trading posts to exchange furs for other necessities.

Treaty of Utrecht

The Treaty of Utrecht brought some peace in 1713, and the Indians swore allegiance to the Colonists at the Treaty of Portsmouth. Meanwhile, the boundary remained contested between New France and New England. England claimed all lands extending to the St. George River, but most Abenaki inhabiting them were sympathetic to the French and to the Catholic Church. In August 1717, Governor Samuel Shute met with tribal representatives of Norridgewock and other Abenaki bands in Georgetown, Maine on a coastal island, warning that cooperation with the French would bring them "utter ruin and destruction", and the Colonists continued to settle on the Kennebec River. Governor-general of New France Vaudreuil wrote in 1720: "Father Rale continues to incite Indians of the mission at [Norridgewock] not to allow the English to spread over their lands."

Indians began to kill cattle, burn haystacks, and otherwise harass Colonial settlers on the Kennebec. Chief Taxous died, and his successor was Wissememet who advocated peace with the Colonists, offering beaver skins as reparation for past damages, and four hostages to guarantee none in the future. Rale, however, continued to stir up individuals within the tribe, urging armed resistance. He declared:

Any treaty with the governor… is null and void if I do not approve it, for I give them so many reasons against it that they absolutely condemn what they have done.[3]

Rale wrote to Vaudreuil for reinforcements, and 250 Abenaki warriors from near Quebec arrived at Norridgewock, reliably hostile to the Colonists. On July 28, 1721, over 250 Indians landed at Georgetown in war paint and flying French colors from a flotilla of 90 canoes. With them were Rale and Superior of the Missions Pierre de la Chasse. They delivered a letter which demanded that the Colonial settlers leave or Rale and his Indians would kill them and burn their houses, together with their livestock. A reply was expected within two months. The Colonists immediately stopped selling gunpowder, ammunition, and food to the Abenaki. Then 300 soldiers under the command of Colonel Thomas Westbrook surrounded Norridgewock to capture Rale in January 1722, while most of the tribe were away hunting, but he was forewarned and escaped into the forest. His strongbox was found among the possessions that he left behind,[4] however, with a hidden compartment containing letters implicating him as an agent of the French government and promising Indians enough ammunition to drive the Colonists from their settlements. Also, inside was his three-volume Abenaki-French dictionary, which was presented to the library at Harvard College.

Father Rale's War

The Abenaki tribe and its auxiliaries burned Brunswick, Maine at the mouth of the Kennebec on June 13, 1722 during Father Rale's War, taking hostages to exchange for those held in Boston as revenge for the raid on Norridgewock. Consequently, Shute declared war on the eastern Indians on July 25; but he then abruptly departed for London on January 1, 1723. He had grown disgusted with the intransigent Assembly which controlled funding, as it squabbled with the Governor's Council over which body should conduct the war. Lieutenant-governor William Dummer assumed management of the government, and further Abenaki incursions persuaded the Assembly to act in what was called Dummer's War.

Battle of Norridgewock

In August 1724, a force of 208 soldiers left Fort Richmond (now Richmond, Maine) in 17 whaleboats up the Kennebec, splitting into two units under the commands of captains Johnson Harmon and Jeremiah Moulton. At Taconic Falls (now Winslow, Maine), 40 men were left to guard the boats as the troops continued on foot. On August 23, 1724 (N. S.), the expedition came unexpectedly upon the village of Norridgewock. The Indians were routed, leaving 26 warriors dead and 14 wounded. Among the casualties was Sébastien Rale.

Rale's scalp and those of the other dead were presented to the authorities in Boston, who had offered a bounty for the scalps of hostile Indians, and Harmon was promoted. Thereafter, the French and Indians claimed that Rale died "a martyr" at the foot of a large cross set in the central square, drawing the soldiers' attention to himself to save his parishioners. The English militia, however, claimed that he was "a bloody incendiary" shot in a cabin while reloading his flintlock musket.

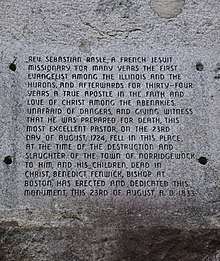

The 150 Abenaki survivors returned to bury the fallen before abandoning Norridgewock for Canada. Rale was interred beneath the altar at which he had ministered to his converts. In 1833, Bishop Benedict Joseph Fenwick dedicated an 11-foot tall obelisk monument erected by subscription over his grave in St. Sebastian's Cemetery at Old Point in Madison, Maine.

Rale remains a polarizing figure. Francis Parkman describes him as:

Fearless, resolute, enduring; boastful, sarcastic, often bitter and irritating; a vehement partisan; apt to see things not as they are, but as he wished them to be… yet no doubt sincere in his opinions and genuine in zeal; hating the English more than he loved the Indians; calling himself their friend, yet using them as instruments of worldly policy, to their danger and final ruin. In considering the ascription of martyrdom, it is to be remembered that he did not die because he was an apostle of the faith, but because he was an active agent of the Canadian government.[5]

On the other hand, historian W. J. Eccles says that, since 1945, some Canadian historians have discarded Parkman's view of the history of New France, as characterized by "prejudice in favor of Anglo-American values, institutions, myths, and aspirations," and the corresponding denigration of Catholic, French, and American Indian elements.[6]

Gallery

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sébastien Rale. |

Grave of Sebastien Rale in 1911

Grave of Sebastien Rale in 1911 Inscription on monument (Latin)

Inscription on monument (Latin) A monument at Father Rale's grave memorializing his work.

A monument at Father Rale's grave memorializing his work.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Charland, Thomas (1979) [1969]. "Rale, Sébastien". In Hayne, David. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- 1 2

- ↑ Parkman, Francis (1892). A half-century of conflict. Boston,.

- ↑ http://www.mainememory.net/bin/Detail?ln=7917

- ↑ Francis Parkman, A Half Century of Conflict, vol. 1, 1893, p. 239

- ↑ Eccles, W. J. (1990). "Parkman, Francis". In Halpenny, Francess G. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. XII (1891–1900) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Bibliography

- John Fiske, New England and New France, 1902, Houghton, Mifflin & Company, Boston, Massachusetts

- Francis Parkman, A Half-Century of Conflict, 1907, Brown, Little & Company, Boston, Massachusetts

- Herbert Milton Sylvester, Indian Wars of New England, Volume III, 1910, W. B. Clarke, Boston, Massachusetts

- THE APOSTLE OF THE ABNAKIS: FATHER SEBASTIAN RALE, S. J. (1657‑1724) The Catholic Historical Review Vol. 1 No. 2 (Jul. 1915), pp164‑174

External links

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Sébastien Rale. |

- Letters - Father Rale

- Norridgewock Indian Village & Monument

- Image of Rale's strongbox at Maine Memory Network

- Clark, William A., "The Church at Nanrantsouak: Sébastien Râle, S.J., and the Wabanaki of Maine's Kennebec River", The Catholic Historical Review, Volume 92, Number 3, July 2006, pp. 225-251, The Catholic University of America Press

- Sebastien Rale - Video on YouTube