Malabar rebellion

| Moplah rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Khilafat Movement, Mappila riots, Tenancy movement, Non-co-operation movement | |||||||

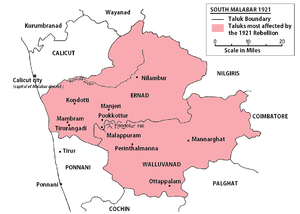

South Malabar in 1921; areas in red show Taluks affected by the rebellion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| British Raj, Hindu landlords | Mappila | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

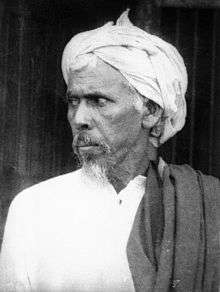

| Thomas T. S. Hitchcock, A. S. P. Amu | Ali Musliyar, Variankunnath Kunjahammad Haji, Sithi Koya Thangal, Chembrassery Thangal, K. Moiteenkutti Haji, Konnara Thangal, Abdu H Hin. | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

British forces: 43 troops killed, 126 troops wounded 100,000 Hindus killed by anti-government rebels[1] | 10,000 killed, 50,000 imprisoned | ||||||

The Malabar rebellion (also known as the Moplah rebellion and Māppila Lahaḷa in Malayalam) was an armed uprising in 1921 against British[2] authority in the Malabar region of Southern India by Mappilas and the culmination of a series of Mappila revolts that recurred throughout the 19th century and early 20th century. The 1921 rebellion began as a reaction against a heavy-handed crackdown on the Khilafat Movement, a campaign in defense of the Ottoman Caliphate,[3] by the British authorities in the Eranad and Valluvanad taluks of Malabar. In the initial stages, a number of minor clashes took place between Khilafat volunteers and the police, but the violence soon spread across the region.[4] The Mappilas attacked and took control of police stations, British government offices, courts and government treasuries. The Moplah rebellion that started as a fight against the British ended in massacre and displacement of Hindus. [5] In the later stages of the uprising, Mappilas prosecute several Indians, who they accused of helping the police to suppress their rebellion.[2][6]

The British policy of divide and rule has not been successful in Malabar. There was a deep social relations between Muslims and Hindus. But outside of Malabar, the British were able to make false propaganda by distributing pamphlets about this struggle as Hindu-Muslim conflict instead of Hindu-Muslim Maitri. The British were able to eliminate the ideological, economic and other support of the Indian nationalist movements to Malabar using these propaganda. The pamphlets which they distributed are still using to mark Malabar rebellion in National History as Hindu-Muslim conflict rather than freedom struggle.

The British Government put down the rebellion with an iron fist, British and Gurkha regiments were sent to the area and Martial Law imposed.[7] One of the most noteworthy events during the suppression later came to be known as the "Wagon tragedy", in which 61 out of a total of 90 Mappila prisoners destined for the Central Prison in Podanur suffocated to death in a closed railway goods wagon.[7]

For six months from August 1921, the rebellion extended over 2,000 square miles (5,200 km2) – some 40% of the South Malabar region of the Madras Presidency.[8] An estimated 10,000 people lost their lives,[9] although official figures put the numbers at 2337 rebels killed, 1652 injured and 45,404 imprisoned. Unofficial estimates put the number imprisoned at almost 50,000 of whom 20,000 were deported, mainly to the penal colony in the Andaman Islands, while around 10,000 went missing.[10] The most prominent leaders of the rebellion were Variankunnath Kunjahammad Haji, Sithi Koya Thangal and Ali Musliyar.[9] Estimates of the number of forced religious conversions range from 180 to 2500; 678 of the 50,000 rebels were charged with this crime.

Contemporary British administrators and modern historians differ markedly in their assessment of the incident, debating whether the revolts were triggered off by religious fanaticism or agrarian grievances.[11] At the time, the Indian National Congress repudiated the movement and it remained isolated from the wider nationalist movement.[12] However, contemporary Indian evaluations now view the rebellion as a national upheaval against British authority and the most important event concerning the political movement in Malabar during the period.[9]

In its magnitude and extent, it was an unprecedented popular upheaval, the likes of which has not been seen in Kerala before or since. While the Mappilas were in the vanguard of the movement and bore the brunt of the struggle, several non-Mappila leaders actively sympathised with the rebels' cause, giving the uprising the character of a national upheaval.[2] In 1971, the Government of Kerala[13] officially recognised the active participants in the events as "freedom fighters".

Background

Land ownership in Malabar

Malabar's agricultural system was historically based on a hierarchy of privileges, rights and obligations for all principal social groups in what British administrator William Logan sometimes referred to as the "Father of Tenancy Legislation" in Malabar,[14] describing it as a system of 'corporate unity’ or joint proprietorship of each of the principal land right holders:[15][16]

Jenmi

The Jenmi, consisting mainly of the Nambudiri Brahmins and Nambiar chieftains, were the highest level of the hierarchy, and a class of people given hereditary land grants by the Naduvazhis or rulers'. The rights conveyed by this janmam were not a freehold in the European sense, but an office of dignity. Owing to their ritual status as priests ( Nambudris ), the jenmis could neither cultivate nor supervise the land but would instead provide a grant of kanam to an individual from the Kanikkaran ethnic group in return for a fixed share of the crops produced. Typically, a jenmi would have a large number of kanikkaran under him.

Kanikkaran (Nairs)

The Kanikkaran, mostly members of the Nair community, were responsible for the security and supervision of the land and distribution of respective shares of produce. Like the jenmi, the kanikkaran was also a part-proprietor of the soil to the extent that one-third of the net produce was his. Each kanikkaran typically had a number of verumpattakkaran under him.

Verum pattakkaran (Mappilas)

The Verumpattakkaran, generally Thiyya and Mappila classes, cultivated the land but were also its part-proprietors. These classes were given a Verum Pattam (Simple Lease) of the land that was typically valid for one year. According to custom, they were also entitled to one-third or an equal share of the net produce.

The net produce of the land was the share left over after providing for the cherujanmakkar or all the other birthright holders such as the village carpenter, the goldsmith and agricultural labourers who helped to gather, prepare and store produce. The system ensured that no jenmi could evict tenants under him except for non-payment of rent. This land tenure system was generally referred to as the janmi-kana-maryada (customary practices).[15][16]

Land reforms and Mappila outbreaks (1836–1921) – Theory of class conflict

During the Mysorean interlude (1788–1792), when the Muslim invasion of Malabar led to widespread atrocities on the Hindu population, the landowners took refuge in neighbouring states. The tenants and the Nair army men who could not escape were forcibly converted into Islam as described in William Logan's Malabar Manual. Thus, the Malabar government under suzerainty of Tipu's Islamic sultanate, having driven out the Hindu Landlords, reached accord with the Muslim Kanakkars. A new system of land revenue was introduced for the first time in the region's history with the government share fixed on the basis of actual produce from the land.[17]

However, within five years, the British took over Malabar defeating and ending Tipu's reign over the region. This allowed the Hindu landlords to return to their homes and regain the lands lost during the Islamic aggression, with the help of the British government and its duly constituted law courts.[18] The British superimposed several Anglo-Roman juridical concepts, such as that of absolute property rights, upon the existing legal system of Malabar. Up until then, such rights had been unknown in the region and as a result all land became the private property of the jenmis. This legal recognition gave them the right to evict tenants, which was in turn enforced through the British civil courts.[16][17] In the words of William Logan:

The (British) authorities, recognised the Janmi as absolute owner of his holding, and therefore free to take as big a share of the produce of the soil as he could get out of the classes beneath him... (Gradually) The British Courts backed up by Police and Magistrates and troops and big guns made the Janmi's independence complete. The hard terms thus imposed on the Kanakkaran had, of course, the effect of hardening the terms imposed by the Kanakkaran on those below him, the Verumpattakkar. The one-third of the net produce to which the Verumpattakkaran was customarily entitled, was more and more encroached upon as the terms imposed on the Kanakkaran became harder and harder. (Government of Madras. 1882, Vol. I: xvii, xxxi–ii)

As conditions worsened, rents rose to as high as 75–80% of net produce, leaving the verumpattakkar cultivators largely "only straw".[17] This caused great resentment among the Mappilas, who, in the words of Logan, were "labouring late and early to provide a sufficiency of food for their wives and children".[16] General resentment amongst the Muslim population led to a long series of violent outbreaks beginning in 1836. These always involved the murder of Hindus, an act which the disgruntled Mappilas regarded as religiously meritorious and as part of their larger obligation to establish an Islamic state. In 1921, for instance, the stated aim was not to oust the Janmi system, but to establish an Islamic nation in Malabar.[8] The British administration referred to the outbreaks as "Moplah outrages", but modern historians tend to treat them as religious outbreaks[19] or expressions of agrarian discontent.[20] The massacre of Hindus and widespread sexual violence in 1921–22 sustained this tradition of violence in Malabar but with one crucial difference: this time it had also a political ideology and a formal organisation.[13][4][15]

Khilafat Movement

According to a 1921 book about the rebellion,

...it was not mere fanaticism, it was not agrarian trouble, it was not destitution, that worked on the minds of Ali Musaliar and his followers. The evidence conclusively shows that it was the influence of the Khilafat and Non-co-operation movements that drove them to their crime. It ia (his which distinguishes the present from all previous outbreaks. Their intention was, absurd though it may seem, to subvert the British Government and to substitute a Khilafat Government by force of arms.(Judgement in Case No. 7 of 1921 on the file of the Special Tribunal, Calicut.) ...[21]

The book further discusses how the Khilafat leader Ali Musaliar rose to prominence at the instance of a Khilafat conference held in Karachi. Also, Ali Musaliar was not a native of Tirurangadi. He had only moved in 14 years earlier. So, there was not class revolt he was handling. It was a Khilafat edifict prepared and passed from a distant Karachi, possibly controlled by spiritual leaders of Islam.

"At this stage, a religious teacher of Tirurangadi named Ali Musaliar rose to prominence as a Khilafat leader. He posed as a great leader of the people. Khilafat and non-co-operation meetings were held regularly under Ali Musaliar, and "these constant preachings, combined with the resolution passed in the All-India Khilafat Conference at Karachi last July, led the ignorant Moplahs to believe that the end of the British Government in India was at hand"[21]

The Khilafat movement was introduced into this happy and peaceful district of Malabar on 28 April 1920, by a Resolution at the Malabar District Conference, held at Manjeri, the headquarters of Ernad Taluk. On 30 March 1921, there was a meeting at which one Abdulla Kutti Musaliar of Vayakkad lectured on Khilafat, in Kizhakoth Amsom, Calicut Taluk. And at a second meeting held the next day at Pannur Mosque, there was some unpleasantness between the Moplahs on one side, and Nayars and Tiyyars, who resented the Khilafat meeting, on the other. Moplahs mustered strong and proceeded to attack the Matom (place of worship) belonging to the Hindu Adhigari of the village.

"It was an organised rising ; the rebels had manufactured war-knives and swords: collected firearms and swords from Hindu houses: also from Police stations: they wrecked the rail-road and cut telegraph lines, destroyed bridges, felled trees and blocked roads, dug trenches and lay in ambush to attack the passing troops : in fact, they acted as men who had gained some little knowledge of modern war-fare, having learned these tactics from disbanded sepoys, who had seen service in Mesopotomia and who, having joined the rebels, instructed these Khilafat soldiery as to how they should proceed."[21]

Nature of crimes

The Moplah rebellion witnessed many cruel attacks on Hindus, and the British officers. The Madras High Court, which adjudicated in this matter had passed judgements on each of the cases against the various Moplah rioters who were captured. The nature of crimes committed, need scrutiny from people, and so has been committed to this article for the world to see and reflect. The nature of crimes was so macabre, that even the writer of the book is confounded that even fanaticism cannot answer such brutality.

The Special Judge who tried the case against the Moplahs remarked, "...to my mind this murderous attack indicate something more than mere fanaticism or lust for looting. There is no evidence that the murders were committed because the murdered persons refused to embrace Islam, or resisted the rebels, or refused to show property. The rebels seem to have meant to kill every male in the place whom they could catch hold of, and the only survivors were those who either got away or were left as dead.."[21]

- "A respectable Nayar lady at Metatur was stripped naked by the rebels in the presence of her husband and brothers, who were made to stand close by with their hands tied behind. When they shut their eyes in abhorrence, they were compelled at the point of the sword to open their eyes and witness the rape committed by these brutes in their presence."[21]

- "Kerala Patrika, Wednesday, March /, 1922. The story of the death of Krishnan Nair will melt even the stoutest heart. He had rendered much help in arresting the rebels. This rankled in the mind of the Mopla and he was killed. First the skin was peeled off from his body, below the waist. He had to suffer this pain for some time. Then his two legs were cut off from the body. He had to suffer pain from this for some time. Ultimately his neck also was cut off."[21]

- Instances are mentioned in which Hindus had actually been forced to dig their own graves before being butchered. It is also reported that diabolical reprisals are being perpetrated against all persons known or suspected of supplying pro- visions to the military and police, one report stating that the Chembrasseri Tangal had ordered a Hindu to be flayed alive for supplying troops with milk.[21]

- An Orgy of Murder. Avokker Musaliar,a rebel leader, established himself with a large following in Muthumana Illom, in Puthur Amsom, Calicut Taluk in October and November 1921.Whoever refused Islam were incontinently and irrevocably ordered to be put to the sword. There is a sacred grove attached to the Illom and in it are a Serpent Shrine and a well. Condemned Hindus were marched to the shrine, beheaded and thrown into the well.[21]

- On the night of 14 November 1921, a large body of armed Moplah entered the house of Puzhikal Narayanan Nair, a wealthy landlord of Nannambra Amsom. They looted the house, carried off one of the girls and a boy captive, murdering the rest, except Narayanan, who escaped. Narayanan Nair trusted his Moplah watchmen, whom he engaged to watch his house and they turned traitors.The girl was rescued from the hands of the rebels after a detention of six weeks and after suffering indescribable indignities.[21]

- A pregnant woman carrying 7 months was cut through the abdomen by a rebel and she was seen lying dead on the way with the dead child projecting out of the womb. Another, a baby of six months was snatched away from the breast of its own mother and cut into two pieces.[21]

- Padmanabhan, Adhikari, Puthur, Calicut mentions — " The Moplahs systematically looted all the houses, some houses being also burnt and destroyed. All the temples in the neighbourhood, about a dozen in number, have been destroyed and the idols completely broken." [21]

- Narrated by refugee: In my Amsom several men and women and children have been murdered by Moplahs. Dead bodies of children and grown up men and women were floating in the river.[21]

- Narrated by refugee: The Keravallur Bhagavathi temple — Karimkali Kavu, Ettaparambil Vishnu Kshetram, Aiyappan Kavu, and these temples have been partly destroyed and the idols have been dug up and removed.[21]( In total, excess of 100 temples were destroyed or desecrated.)

- Narrated by refugee: There are six temples in the Amsom, all of them have been destroyed and desecrated and cows slaughtered in the premises and the idols were garlanded with the entrails and the skulls hung in various places in the temples. Six Hindus have been murdered and about 15 houses burnt by the rebels. About sixty persons were forcibly converted.[21]

Appendix IX of the book[21] captures the nature of the atrocities

(a) Brutally dishonoring women,

(b) Flaying people alive,

(c) Wholesale slaughter of men, women and children,

(d) Forcibly converting people in thousands, and murdering those who refused to be converted in utter cold blood.

(e) Throwing half-dead people into wells, and leaving the victims for hours, to struggle till finally released from their sufferings by death.

(f) Burning a great many and looting practically all Hindu and Christian houses, in the disturbed area, in which even Mopla women and children took part, and robbing women, of even the garments on their bodies, in short reducing the whole non-Moslem population to abject destitution.

(g) Cruelly insulting the religious sentiments of the Hindus, by desecrating and destroying numerous temples, in the disturbed area, killing cows within the temple precincts, putting their entrails on the holy images and hanging the skulls on the walls and roofs.[21]

Aftermath of the Moplah riots

The following were the various leaders of the movement who were sentenced to death following the Moplah riots

- Ali Musaliar (leader of the movement)

- Kunhi Kadir, Khilafat Secretary, Tanur

- Variankunnath Kunhammad Haji

- Kunhj Koya, Thangal, president of the Khilafat Committee, Malappuram

- Koya Tangal of Kumaramputhur, Governor of a Khilafat Principality

- Chembrasseri Imbichi Koya Thangal (notorious for his killing of 38 men by slashing the necks and throwing them into a well)

- Palakamthodi Avvocker Musaliar

- Konnara Mohammed Koya Thangal

On 19 November 1921, about 100 Moplah prisoners were sent by train from Malabar to Coimbatore. They were packed in goods wagons which, of course, had no ventilation. So, when the doors were opened after a five hours’ journey, the prisoners were found to be in a state of collapse, with horrible wounds inflicted by bites and bows in one another by the struggling men. In all, 82 men died.

In the aftermath of this ethnic cleansing, the Suddhi Movement was created by the Arya Samaj. They converted over 2000 Hindus who had been forcibly converted to Islam by the Moplahs. However their leader, Swami Shraddhananda, had to pay with his life, due to this effort. The aged Swami was stabbed on 23 December 1926 by a person named Abdul Rashid at his Ashram.

Rebellion and response

On 20 August 1921, the police attempted to arrest Vadakkevittil Muhammed, the secretary of the Khilafat Committee of Ernad at Pookkottur, alleging that he had stolen the pistol of a Hindu Thirumulpad from a Kovilakam (manor) in Nilambur. A crowd of 2,000 Mappilas from the neighbourhood foiled the attempt, but on the following day a squad of police arrested a number of Khilafat volunteers and seized records at the Mambaram mosque in Tirurangadi, leading to rumours that the building had been desecrated. A large crowd of Mappilas converged on Tirurangadi and besieged the local police station. The police opened fire on the crowd, triggering a furious reaction which soon engulfed the Eranad and Valluvanad taluks along with neighbouring areas and continued for over two months.[7]

Following the mosque incident, the rebels attacked and seized police stations, government treasuries, and entered the courts and registry offices where they destroyed records. Some even climbed into the judges' seats and proclaimed the advent of swaraj (self-rule). The rebellion soon spread to the neighbouring areas of Malappuram, Manjeri, Perinthalmanna, Pandikkad and Tirur under principle leaders Variankunnath Kunjahammad Haji, Seethi Koya Thangal of Kumaranpathor and Ali Musliyar. By 28 August 1921, British administration had virtually come to an end in Malappuram, Tirurangadi, Manjeri, and Perinthalmanna, which then fell into the hands of the rebels who established complete domination over the Eranad and Valluvanad Taluks. On 24 August 1921, Variankunnath Kunjahammad Haji took over command of the rebellion from Ali Musliyar. Public proclamations were issued by Variyankunnath and Seethi that no harm should come to Hindus and that those Mappilas who resorted to looting would receive exemplary punishments.[2]

During the initial stages of the rebellion, the British military and police were forced to withdraw from these areas but by the end of August several contingents of British troops and Gurkha arrived. Clashes with the rebels followed, one of the most notable encounters taking place at Pookkottur (often referred by the Moplahs as Pookkottur War), in which British troops sustained heavy casualties and had to retreat to safety.[2]

During the early phase of the rebellion, the targets were primarily the jenmis and the British Government. Crimes committed by some of the rebels were accepted by leaders.Very quickly it turned out aimed at Hindus irrepective of their caste. After the proclamation of Martial law and the arrival of the British army, when some members of the Hindu community were enlisted by the army to provide information on the rebels.[2][6] Once they had eliminated the minimal presence of the government, the Moplahs turned their full attention to attacking Hindus while Ernad and Valluvanad were declared Khilafat kingdoms.[22]

By the end of 1921, the situation was brought under control. The British administration raised a special quasi-military (or Armed Police) battalion, the Malabar Special Police (MSP), initially consisting of non-Muslims and trained by the British Indian Army. The MSP then attacked the rioters and eventually subdued them.

Reactions

"The blood-curdling atrocities committed by the Moplas in Malabar against the Hindus were indescribable. All over Southern India, a wave of horrified feeling had spread among the Hindus of every shade of opinion, which was intensified when certain Khilafat leaders were so misguided as to pass resolutions of " congratulations to the Moplas on the brave fight they were conducting for the sake of religion". Any person could have said that this was too heavy a price for Hindu-Muslim unity. But Mr. Gandhi was so much obsessed by the necessity of establishing Hindu-Muslim unity that he was prepared to make light of the doings of the Moplas and the Khilafats who were congratulating them. He spoke of the Moplas as the "brave God-fearing Moplas who were fighting for what they consider as religion and in a manner which they consider as religious ".[23]

Swami Shraddhanand in the Liberator of 26 August 1926:[24]

The original resolution condemned the Moplas wholesale for the killing of Hindus and burning of Hindu homes and the forcible conversion to Islam. The Hindu members themselves proposed amendments till it was reduced to condemning only certain individuals who had been guilty of the above crimes. But some of the Moslem leaders could not bear this even. Maulana Fakir and other Maulanas, of course, opposed the resolution and there was no wonder. But I was surprised, an out-and-out Nationalist like Maulana Hasrat Mohani opposed the resolution on the ground that the Mopla country no longer remained Dar-ul-Aman but became Dar-ul-Harab and they suspected the Hindus of collusion with the British enemies of the Moplas. Therefore, the Moplas were right in presenting the Quran or sword to the Hindus. And if the Hindus became Mussalmans to save themselves from death, it was a voluntary change of faith and not forcible conversion—Well, even the harmless resolution condemning some of the Moplas was not unanimously passed but had to be accepted by a majority of votes only.

The Viceroy, Lord Reading:

Their wanton and unprovoked attack on the Hindus, the all but wholesale looting of their houses in Ernad etc, the forcible conversion of Hindus in the beginning of the Moplah rebellion and the wholesale conversion of those who stuck to their homes in later stages, the brutal murder of inoffensive Hindus without the slightest reason except that they are “Kafirs” or belonged to the same religion as the policemen, who their mosques, burning of Hindu temples, the outrage on Hindu women and their forcible conversion and marriage by the Moplahs.

The Rani of Nilambur in a petition to Lady Reading:[21]

But it is possible that your Ladyship is not fully apprised of all the horrors and atrocities perpetrated by the fiendish rebels; of the many wells and tanks filled up with the mutilated, but often only half dead bodies of our nearest and dearest ones who refused to abandon the faith of our fathers;of pregnant women cut to pieces and left on the roadsides and in the jungles,with the unborn babe protruding from the mangled corpse; of our innocent and helpless children torn from our arms and done to death before our eyes and of our husbands and fathers tortured, flayed and burnt alive; of our hapless sisters forcibly carried away from the midst of kith and kin and subjected to every shame and outrage which the vile and brutal imagination of these inhuman hell-hounds could conceive of; of thousands of our homesteads reduced to cinder-mounds out of sheer savagery and a wanton spirit of destruction; of our places of worship desecrated and destroyed and of the images of the deity shamefully insulted by putting the entrails of slaughtered cows where flower garlands used to lie or else smashed to pieces; of the wholesale looting of hard-earned wealth of generations reducing many who were formerly rich and prosperous to publicly beg for a piece or two in the streets of Calicut, to buy salt or chilly or betel-leaf - rice being mercifully provided by the various relief agencies.

Citing narratives available to him regarding the actions of the Mappilas during the rebellion, C. Sankaran Nair wrote a strongly worded criticism of Gandhi and his support for the Khilafat Movement, accusing him of being an anarchist. He was highly critical of the "sheer brutality" of the atrocities committed on women during the rebellion, finding them "horrible and unmentionable". In particular, he referred to a resolution under the Zamorin Raja of the time and an appeal by the Rani of Nilambur. He further wrote:

"The horrid tragedy continued for months. Thousands of Mahomedans killed, and wounded by troops, thousands of Hindus butchered, women subjected to shameful indignities, thousands forcibly converted, persons flayed alive, entire families burnt alive, women it is said hundreds throwing themselves into wells to avoid dishonour, violence and terrorism threatening death standing in the way of reversion to their own religion. This is what Malabar in particular owes to the Khilafat agitation, to Gandhi and his Hindu friends."[25]

A conference held at Calicut presided over by the Zamorin of Calicut, the Ruler of Malabar issued a resolution:[26]

"That the conference views with indignation and sorrow the attempts made at various quarters by interested parties to ignore or minimise the crimes committed by the rebels such as: brutally dishonouring women, flaying people alive, wholesale slaughter of men, women and children, burning alive entire families, forcibly converting people in thousands and slaying those who refused to get converted, throwing half dead people into wells and leaving the victims to struggle for escape till finally released from their suffering by death, burning a great many and looting practically all Hindu and Christian houses in the disturbed areas in which even Moplah women and children took part and robbed women of even the garments on their bodies, in short reducing the whole non-Muslim population to abject destitution, cruelly insulting the religious sentiments of the Hindus by desecrating and destroying numerous temples in the disturbed areas, killing cows within the temple precincts putting their entrails on the holy image and hanging skulls on the walls and the roofs."

Wagon incident

Statistics

| Name of Taluka | Moplah population (1921) | Hindu population (1921) |

|---|---|---|

| Calicut | 88393 | 196435 |

| Chirakkal | 87337 | 25498 |

| Cochin | 4999 | 7318 |

| Eranad | 237402 | 163328 |

| Kottayam | 55146 | 175048 |

| Kurumbranad | 96463 | 259799 |

| Palghat | 47946 | 315432 |

| Ponnani | 229016 | 281155 |

| Walluvanad | 133919 | 259979 |

| Wayanad | 14252 | 67845 |

According to official records, the British government lost 43 troops with 126 wounded,[27] while 2337 rebels were killed, another 1652 injured and 45,404 imprisoned. Unofficial estimates put the number at 10,000 Mappilas killed[9] and 50,000 imprisoned, of who 20,000 were deported (mainly to the penal colony in the Andaman Islands) while around 10,000 went missing.[10] The number of civilian casualties is estimated at between 500 and 600.[4]

Official estimates of forced religious conversions were put at 180, but unofficial estimates suggest a figure of between 1000 and 1500. Arya Samaj sources reported a number of 1766, adding that the total might exceed 2500,[2] the highest estimate made.[28] Out of a total of almost 50,000 Mappilas involved in the rebellion, 678 were charged with the crime of forced religious conversion, not all of who were guilty of involvement.[29]

Within five years subsequent to the conflict the agricultural output was averaging slightly more than prior to it. Qureshi has said that, "In short, contrary to popular belief, Malabar did not suffer a massive devastation, and even if it did the recovery was miraculous."[30]

Popular culture

Renowned author Uroob's masterpiece novel Sundarikalum Sundaranmarum (The Beautiful and the Handsome) is set in the backdrops of Malabar Rebellion. The novel has about thirty characters belonging to three generations of eight families belonging to Malabar during the end of the Second World War. Sundarikalum Sundaranmarum won the Kendra Sahitya Akademi Award, India's most prestigious literary award, in 1960. It also received the Asan Centenary Award in 1973, a special award given by the Kerala Sahitya Akademi for the most outstanding work since Independence.

The 1988 Malayalam language film 1921 or Ayirathi Thollayirathi Irupathonnu (English title: Nineteen Twenty One), directed by I. V. Sasi and written by T. Damodaran, depicts the events of the rebellion. The film stars Mammootty as Khadir, a retired Mappila soldier, alongside Madhu as Ali Musliyar. The film won the Kerala State Film Award for Best Film with Popular Appeal and Aesthetic Value in the same year.[31]

The rebellion also spawned a large number of Mappila Songs.[32] Many of these describe the events surrounding the Khilafat movement in Malabar and offer a view of conditions in the area at the time. Ahmed Kutty composed the Malabar Lahala enna Khilafat Patt in 1925, which describes the events of the rebellion. Many of rebel prisoners such as Tannirkode Ossankoya composed songs in their letters to relatives.[33]

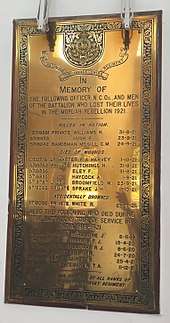

Monuments

The officers and men from the Dorset Regiment who lost their lives while taking part in the suppression of the revolt are commemorated in a brass tablet at the St. Mark's Cathedral, Bangalore.[34]

The Variyankunnath Kunjahammad Haji memorial town hall in Malappuram Municipality[35] is named after the leader of the rebellion while the Tirur Wagon Tragedy memorial townhall commemorates the eponymous incident.[36] The Pookkottur war memorial gate is dedicated to those killed in the Pookkottur battle.[37][38]

Along with these monuments, abandoned graves of British officers who lost their lives during the rebellion can be seen in Malabar. This include that of Private F. M. Eley, Private H. C. Hutchings (both died of wounds received in action against the Moplahs at Tirurangadi on 22 July 1921), William John Duncan Rowley (Assistant Suprededent of Police, Palghat, killed at Tirurangadi by a mob of Moplahs at the outbreak of the rebellion on 20 August 1921 – aged 28).

See also

References

- ↑ Besant, Annie. The Future of Indian Politics: A Contribution To The Understanding Of Present-Day Problems P252. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 1-4286-2605-0.

They murdered and plundered abundantly, and killed or drove away all Hindus who would not apostatize. Somewhere about a lakh of people were driven from their homes with nothing but the clothes they had on, stripped of everything. Malabar has taught us what Islamic rule still means, and we do not want to see another specimen of the Khilafat Raj in India.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pg 179–183, Kerala district gazetteers: Volume 4 Kerala (India), A. Sreedhara Menon, Superintendent of Govt. Presses https://books.google.com/books?id=ZF0bAAAAIAAJ

- ↑ "Khilafat movement". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Pg 447, Pan-Islam in British Indian politics: a study of the Khilafat Movement, 1918–1924 M. Naeem Qureshi BRILL, 1999

- ↑ "The Moplah Rebellion of 1921". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- 1 2 Page 622 , Peasant struggles in India, AR Desai, Oxford University Press – 1979

- 1 2 3 http://www.kerala.gov.in -> History -> Malabar Rebellion

- 1 2 Pg 58, The Mappilla Rebellion, 1921: Peasant Revolt in Malabar, Robert L. Hardgrave, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1 (1977), Cambridge University Press

- 1 2 3 4 Pg 361, A short survey of Kerala History, A. Sreedhara Menon, Vishwanathan Publishers 2006

- 1 2 Pg 45, Malabar: Desheeyathayude idapedalukal ( Malabar: involvement of nationalism), MT Ansari, DC Books

- ↑ K. N. Panikkar, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 17, No. 20 (15 May 1982), pp. 823–824

- ↑ Pg 67, The labor of development: workers and the transformation of capitalism in Kerala, India, Patrick Heller, Cornell University Press, 1999

- 1 2 Kupferschmidt, Uri M. (1 January 1987). "The Supreme Muslim Council: Islam Under the British Mandate for Palestine". BRILL. Retrieved 25 April 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Pg 80 Modern Kerala: studies in social and agrarian relations, K. K. N. Kurup, Mittal Publications, 1988

- 1 2 3 Pg 17–20, Peasant Struggles, Land Reforms and Social Change: Malabar 1836–1982 By P Radhakrishnan – COOPERJAL

- 1 2 3 4 Pg 1- 24, Tenancy legislation in Malabar, 1880–1970: an historical analysis , V. V. Kunhi Krishnan (Ph.D Thesis under Dr. K. K. N. Kurup, Calicut University ), Northern Book Centre, 1993

- 1 2 3 Pg 53, Kerala Development Report, Government of India Planning Commission, Academic Foundation, 2008

- ↑ Logan, 1951b:209-10.

- ↑ Mazumdar, 1973; Ravindran, 1973; Dale, 1980.

- ↑ Houtart and Lemercinier, 1978; Namboodiripad, 1943:1–2; Panikkar. 1979:611; Wood, 1974.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Gopalan Nair, Diwan Bahadur (1922). Moplah Rebellion , 1921. https://archive.org/stream/MoplahRebellion1921/Moplah%20rebellion,%201921_djvu.txt: Norman Printing Bureau. p. 8.

- ↑ O P Ralhan (1996). Encyclopaedia of Political Parties: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh : National, Regional, Local. Anmol Publications PVT . LTD. p. 297.

- ↑ Ambedkar, Bhimrao. Pakistan or the Partition of India. pp. Chapter 6.

- ↑ Shraddanand, Swami (26 August 1926). "The Liberator".

- ↑ Nair, Sankaran. Gandhi and Anarchy. Mittal Publications. pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1 January 1977). "History of the Freedom Movement in India". Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay. Retrieved 25 April 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Pg 20, Papers by command: Volume 16 , Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons – 1922

- ↑ Pg 242–243 , Malabar Kalapam , M. Gangadharan , D.C. Books

- ↑ Pg 196, Malabar Kalapam, Prabhuthvathinum Rajavaazchakkum ethire (Malabar Rebellion, Against Lord and the State), K.N. Panikkar, D.C. Books

- ↑ Qureshi, M. Naeem (1999). Pan-Islam in British Indian politics: a study of the Khilafat Movement, 1918–1924. BRILL. p. 454. ISBN 9789004113718.

- ↑ "official website of INFORMATION AND PUBLIC RELATION DEPARTMENT OF KERALA". Kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ↑ Pg 452, Asian journal of social science, Volume 35, Issues 1–5, Brill, 2007

- ↑ Congress, South Indian History (1 January 1988). "Proceedings of the ... Annual Conference ..." The Congress. Retrieved 25 April 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ David, Stephen (9 January 2009). "200 years of Bangalore's oldest Christian landmark". India Today. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "The Hindu : Engagements / Palakkad : In Palakkad Today". HinduOnNet.com. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "Battle of Pookottur commemorated". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 27 August 2009.

- ↑ "Pookkottur Grama Panchayat". lsgkerala.in. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

Further reading

- Adrija Roychowdhury, Fact checking BJP’s Kummanam Rajasekharan: Was the Malabar rebellion a case of Jihad?, Indian Express, 12 October 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malabar rebellion. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Malabar rebellion |