Kennebec River

| Kennebec River | |

|---|---|

|

Wyman Lake on the Kennebec River in Somerset County, Maine | |

| Country | United States |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source |

Moosehead Lake 1,024 feet (312 m) |

| River mouth | Gulf of Maine, North Atlantic Ocean |

| Length | 170 miles (270 km) |

| Discharge |

|

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 5,869 sq mi (15,200 km2) |

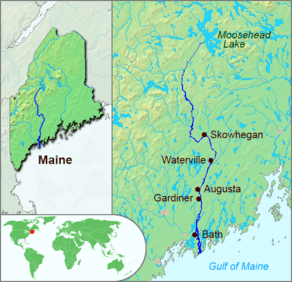

The Kennebec River is a 170-mile-long (270 km)[1] river within the U.S. state of Maine.

It rises in Moosehead Lake in west-central Maine. The East and West Outlets join at Indian Pond and the river then flows southward from Harris Station Dam, the largest hydroelectric dam in the state. It is joined at The Forks by the Dead River, also called the West Branch,[2] then continues south past the cities of Madison, Skowhegan, Waterville, and the state capital Augusta. At Richmond, it flows into Merrymeeting Bay, a 16-mile-long (26 km) freshwater tidal bay into which also flow the Androscoggin River and five smaller rivers. The Kennebec then runs past the shipbuilding center of Bath, then to the Gulf of Maine in the Atlantic Ocean. Ocean tides affect the river height as far north as Waterville. Tributaries of the Kennebec River include the Carrabassett River, Sandy River, and Sebasticook River.

Segments of the East Coast Greenway run along the Kennebec.

Etymology

The name "Kennebec" comes from the Eastern Abenaki /kínipekʷ/, meaning "large body of still water, large bay".[3]

History

The Abenaki village of Norridgewock was located on the Kennebec in the 1600s.

Discovery by Europeans

Champlain_Samuel_btv1b2000019z.jpg)

In 1605 Samuel de Champlain navigated the coast of what is now Maine, charting the land and rivers of what was then called "La Nouvelle France", "L'Acadie" or "La Cadie" including the Kennebec as far up as Bath, as well as the St. Croix, and Penobscot rivers[4]

Shipbuilding

The English Popham Colony was founded on the Kennebec in 1607. The settler built the Virginia of Sagadahoc, the first oceangoing vessel built in the New World by English-speaking shipwrights. Hundreds of wooden and steel vessels have since been launched on the Kennebec, particularly in Bath, the so-called "City of Ships", including the Wyoming, one of the largest wooden schooners ever built.

Following the War of 1812, Bath and the rest of the country experienced a lengthy period of expansion of international trade and therefore of maritime fleets. Many of those ships were built in Bath. In 1854, at the peak of this boom period, at least nineteen major firms were building ships in Bath.[5] The sole remaining shipyard is the Bath Iron Works, owned by General Dynamics, one of the few yards still building warships for the United States Navy. The USCGC Kennebec was named after this river.

An English trading post, Cushnoc, was established on the Kennebec in 1628.

Navigation

The Kennebec River was an early trade corridor to interior Maine from the Atlantic coast. Ocean ships could navigate upstream to Augusta. The cities of Bath, Gardiner, Hallowell and Augusta, and the towns of Woolwich, Richmond and Randolph developed adjacent to that transportation corridor. The river upstream of Augusta became an important transportation corridor for log driving to bring wooden logs and pulpwood from interior forests to sawmills and paper mills built to use water power where the city of Waterville and the towns of Winslow, Skowhegan, Norridgewock, Madison, Anson, and Bingham developed. The Maine Central Railroad and U.S. Route 201 were later constructed following the river through these towns and cities.[6]

Father Rale's War

England's 1710 conquest of Acadia brought mainland Nova Scotia under English control, but New France still claimed present-day New Brunswick and present-day Maine east of the Kennebec River. (The Kennebec River was also a border for the Natives.[7]) To secure its claim, New France established Catholic missions in the three largest native villages in the region: one on the Kennebec River (Norridgewock); one further north on the Penobscot River (Penobscot) and one on the Saint John River (Medoctec).[8][9] Continued encroachments led to Kennebec Abenaki warriors taking up arms in what Yankee historians sometimes refer to as Father Rale's War (1722–1725). A Yankee militia raid on the Abenaki Indian mission village at Norridgewock in August 1724 dealt the Abenaki resistance a crippling blow. As many as 40 inhabitants were killed, including women and children, as well Sebastien Rasle. The 67-year old Jesuit priest was scalped, as were 26 of the Abenaki who had been slaughtered. Having plundered and torched the tribal village, the Yankee raiders destroyed the surrounding corn fields and obtained bounty for the scalps. Some Abenaki survivors returned to the Upper Kennebec, but others were welcomed by their Penobscot allies or found permanent refuge in Abenaki mission villages in French Canada.[10]

Revolutionary War

1,110 American Revolutionary War soldiers followed this route during Benedict Arnold's expedition to Quebec in 1775.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, near the Kennebec River, the Battle of Hampden was fought in Maine.

Ice industry

In 1814, Frederic Tudor began to establish markets in the West Indies and the southern United States for ice. In 1826, Rufus Page built the first large ice house near Gardiner to supply Tudor. The ice was harvested by farmers and others who were inactive due to the winter weather. The ice was cut by hand, floated to an ice house on the bank, and stored until spring. Then, packed in sawdust, it was loaded aboard ships and sent south.[11]

Edwards Dam

The Kennebec River before the construction of Edwards Dam was extremely important as a spawning ground for Atlantic fish. In 1837, the Edwards Dam was built across the Kennebec River, just shy of the limit of tidal influence. Made of timber and concrete, it extended 917 feet (280 m) across the river and 25 feet (7.6 m) high. Its reservoir stretched 17 miles (27 km) upstream, and covered 1,143 acres (4.63 km2). In 1999, the dam was removed.

Flood of 1987

On April 1, 1987, over 6 feet (1.8 m) of melting snow and 4 to 6 inches (100 to 150 mm) of rain in the mountains forced the river to flood its banks. By April 2, 1987, the river had crested at 34.1 ft (10.4 m) above the normal 13 ft (4.0 m) flood stage, meaning the river rose 21 ft (6.4 m). At the flood's peak, the flow topped out at an estimated 194,000 cubic feet per second (5,500 m3/s). It caused about $100 million in damage (171 million in 2008 dollars),[12] flooding 2,100 homes, destroying 215, and damaging 240 others. Signs of the flood can still be found around the towns and cities that line the river.

Whitewater Rafting

In 1976 Suzanne and Wayne Hockmeyer, of Kennebec Whitewater Expeditions now Northern Outdoors, pioneered whitewater rafting through the Kennebec gorge just below Harris Station Dam.[13] Today, Northern Outdoors and 22 other rafting companies in The Forks raft the river daily from May through October. Four times per rafting season Brookfield Power tests their generating turbines by releasing the maximum amount of water possible from Harris Station Dam. At 8000 cubic feet per second these Kennebec River Turbine Tests are the biggest whitewater releases in Maine.[14]

Natural resources

Prior to the industrial era, the river contained many anadromous fish, in particular the Atlantic salmon. The exploiting of hydroelectric power in the region reduced the runs of such fish. The removal of dams on the river has been a controversial local issue in recent years. The removal of the Edwards Dam in 1999 has led to increased anadromous activity on the river.

Statistics

The river drains 5,869 square miles (15,200 km2), and on average discharges 5.893 billion US gallons (22,310,000 m3) per day into Merrymeeting Bay at a rate of 9,111 cubic feet per second (258.0 m3/s). The United States government maintains three river flow gauges on the Kennebec river. The first is at Indian Pond (45°30′40″N 69°48′39″W / 45.51114°N 69.81080°W) where the rivershed is 1,590 square miles (4,100 km2). Flow here has ranged from 161 to 32,900 cubic feet per second (4.6 to 931.6 m3/s). The second is at Bingham (45°3′6″N 69°53′12″W / 45.05167°N 69.88667°W) where the rivershed is 2,715 square miles (7,030 km2). Flow here has ranged from 110 to 65,200 cu ft/s (3.1 to 1,846.3 m3/s). The third is at North Sidney (44°28′21″N 69°41′09″W / 44.47250°N 69.68583°W) where the rivershed is 5,403 square miles (13,990 km2). Flow here has ranged from 1,160 to 232,000 cu ft/s (33 to 6,570 m3/s). Two additional river stage gauges (no flow data) are in Augusta (44°19′06″N 69°46′17″W / 44.31833°N 69.77139°W) and Gardiner (44°13′50″N 69°46′16″W / 44.23056°N 69.77111°W); both of these gauge heights are affected by ocean tides.[15]

Before the river was dammed, it was navigable as far as Augusta.

See also

References

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-04-05 at WebCite, accessed June 30, 2011

- ↑ John F. Hall, The Upper Kennebec Valley, p. 7. The main stem from Indian Pond was sometimes called the East Branch.

- ↑ Bright, William (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ Seymour I. Schwartz (October 2008). The Mismapping of America. University Rochester Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-58046-302-7.

- ↑ "Bath's Historic Downtown - History Overview". bath.mainememory.net.

- ↑ Delorme Mapping Company The Maine Atlas and Gazetteer (13th edition) (1988) ISBN 0-89933-035-5 maps 6,12,13,20,21&30

- ↑ Bourque, Bruce (1 July 2004). "Twelve Thousand Years: American Indians in Maine". U of Nebraska Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Meductic Indian Village / Fort Meductic National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- ↑ John Grenier, The Far Reaches of Empire. University of Oklahoma Press, 2008, p. 51, p. 54.

- ↑ Prins, Harald E.L. 1984 'Foul Play on the Kennebec: The Historical Background of Fort Western and the Demise of the Abenaki Nation.' The Kennebec Proprietor, Vol. 1 (3), pp.4-14.

- ↑ Maine's Ice Industry by Richard Judd in Maine The Pine Tree State form Prehistory to the present

- ↑ http://www.state.me.us/mema/mema_news_display.shtml?id=35848

- ↑ "About Northern Outdoors, Maine Rafting Resort Pioneer". Northern Outdoors. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ↑ "Kennebec River Turbine Test Releases - Maine White Water Rafting". Northern Outdoors. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ↑ G.J. Stewart; J.P. Nielsen; J.M. Caldwell; A.R. Cloutier (2002). "Water Resources Data - Maine, Water Year 2001" (PDF). Water Resources Data - Maine, Water Year 2001. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Kennebec River. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kennebec River. |

- MaineRivers.org Kennebec River profile

- Real-time flow or stage data for The Forks, Bingham, North Sidney, Augusta, and Gardiner gages.

- Kennebec-Chaudiere Kennebec-Chaudiere International Corridor