Petra

| Petra Raqmu | |

|---|---|

|

Tourists in front of Al Khazneh (The Treasury) at Petra | |

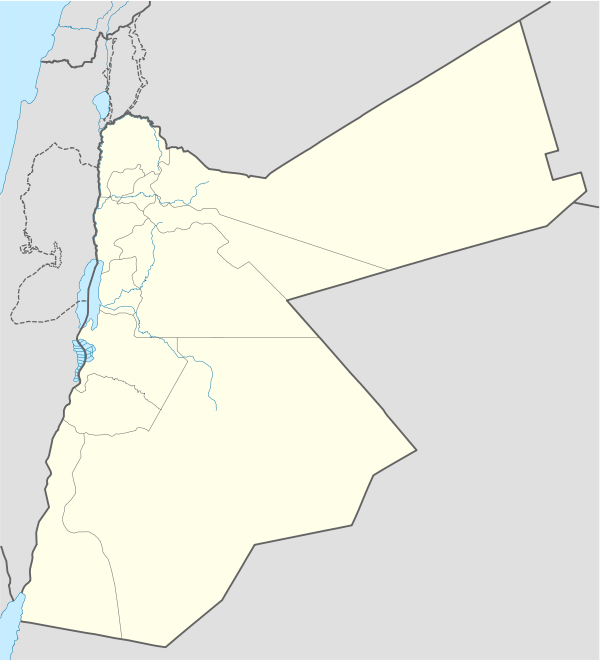

| Location | Ma'an Governorate, Jordan |

| Coordinates | 30°19′43″N 35°26′31″E / 30.32861°N 35.44194°ECoordinates: 30°19′43″N 35°26′31″E / 30.32861°N 35.44194°E |

| Area | 264 square kilometres (102 sq mi)[1] |

| Elevation | 810 m (2,657 ft) |

| Built | possibly as early as 5th century BC [2] |

| Visitors | 596,602 (in 2014) |

| Governing body | Petra Region Authority |

| Website | www.visitpetra.jo |

Location of Petra Raqmu in Jordan | |

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, iv |

| Reference | 326 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

Petra (Arabic: البتراء, Al-Batrāʾ; Ancient Greek: Πέτρα), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu, is a historical and archaeological city in southern Jordan. Petra lies on the slope of Jabal Al-Madbah in a basin among the mountains which form the eastern flank of Arabah valley that run from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba.[3] According to Hieronymus of Cardia, the name "Petra" was given by Greek merchants, who observed the city's inhabitants offering sacrifice, in springtime, to a deity on a large stone, i.e. petra. Petra is believed to have been settled as early as 9,000 BC, and it was possibly established in the 4th century BC as the capital city of the Nabataean Kingdom. The Nabataeans were nomadic Arabs who invested in Petra's proximity to the trade routes by establishing it as a major regional trading hub.[4]

The trading business gained the Nabataeans considerable revenue and Petra became the focus of their wealth. The earliest historical reference to Petra was the attack to the city ordered by Antigonus I in 312 BC recorded by various Greek historians. The Nabataeans were, unlike their enemies, accustomed to living in the barren deserts, and were able to repel attacks by utilizing the area's mountainous terrain. They were particularly skillful in harvesting rainwater, agriculture and stone carving. Most of the Nabataean rulers embraced Greek culture, first of which was Aretas III Philhellen (87-62 BC), up to the last Nabataean ruler, Rabbel II Soter (70-106 AD). Petra flourished in the 1st century AD when its famous Khazneh structure –believed to be the mausoleum of Nabataean King Aretas IV– was constructed using Greek architectural elements, and its population peaked at an estimated 20,000 inhabitants.[5]

Although the Nabataean Kingdom became a client state for the Roman Empire in the first century BC, it was only in 106 AD that they lost their independence. Petra fell to the Romans who annexed and renamed Nabataea to Arabia Petraea. Petra's importance declined as sea trade routes emerged, and after a 363 earthquake destroyed many structures. The Byzantine Era witnessed the construction of several Christian churches, but the city started to decline after attacks due to the emerging Sasanid Empire, and by the early Islamic era became an abandoned place where only a handful of nomads lived. It remained unknown to the world until it was rediscovered in 1812 by Johann Ludwig Burckhardt.[6]

The city is accessed through a 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) long gorge called the Siq, which leads directly to the Khazneh. Famous for its rock-cut architecture and water conduit system, Petra is also called the Rose City due to the color of the stone out of which it is carved.[7] It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985. UNESCO has described it as "one of the most precious cultural properties of man's cultural heritage".[8] In 2007, Al-Khazneh was voted in as one of the New7Wonders of the World. Petra is a symbol of Jordan, as well as Jordan's most-visited tourist attraction. Tourist numbers peaked at 1 million in 2010, the following period witnessed a slump due to regional instability. However, tourist numbers have picked up recently, and around 600,000 tourists visited the site in 2017.

Geography

Pliny the Elder and other writers identify Petra as the capital of the Tadeanos and the center of their caravan trade. Enclosed by towering rocks and watered by a perennial stream, Petra not only possessed the advantages of a fortress, but controlled the main commercial routes which passed through it to Gaza in the west, to Bosra and Damascus in the north, to Aqaba and Leuce Come on the Red Sea, and across the desert to the Persian Gulf.[3]

Excavations have demonstrated that it was the ability of the Nabataeans to control the water supply that led to the rise of the desert city, creating an artificial oasis. The area is visited by flash floods, and archaeological evidence demonstrates the Nabataeans controlled these floods by the use of dams, cisterns and water conduits. These innovations stored water for prolonged periods of drought and enabled the city to prosper from its sale.[9][10]

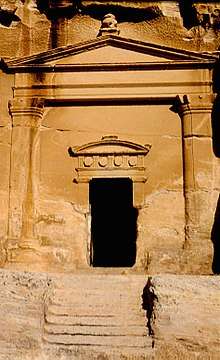

In ancient times, Petra might have been approached from the south on a track leading across the plain of Petra, around Jabal Haroun ("Aaron's Mountain"), the location of the Tomb of Aaron, said to be the burial-place of Aaron, brother of Moses. Another approach was possibly from the high plateau to the north. Today, most modern visitors approach the site from the east. The impressive eastern entrance leads steeply down through a dark, narrow gorge (in places only 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft) wide) called the Siq ("the shaft"), a natural geological feature formed from a deep split in the sandstone rocks and serving as a waterway flowing into Wadi Musa. At the end of the narrow gorge stands Petra's most elaborate ruin, Al Khazneh (popularly known as and meaning "the Treasury"), hewn into the sandstone cliff. While remaining in remarkably preserved condition, the face of the structure is marked by hundreds of bullet holes made by the local Bedouin tribes that hoped to dislodge riches that were once rumored to be hidden within it.[11]

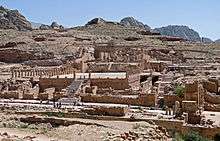

A little further from the Treasury, at the foot of the mountain called en-Nejr, is a massive theatre, positioned so as to bring the greatest number of tombs within view. At the point where the valley opens out into the plain, the site of the city is revealed with striking effect. The amphitheatre has been cut into the hillside and into several of the tombs during its construction. Rectangular gaps in the seating are still visible. Almost enclosing it on three sides are rose-colored mountain walls, divided into groups by deep fissures and lined with knobs cut from the rock in the form of towers.[3]

History

Indigenous rule

| Historical Arab states and dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient Arab States

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eastern Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Western Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arabian Peninsula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current monarchies

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By 2010 BC, some of the earliest recorded farmers had settled in Beidha, a pre-pottery settlement just north of Petra.[12] Petra is listed in Egyptian campaign accounts and the Amarna letters as Pel, Sela or Seir. Though the city was founded relatively late, a sanctuary has existed there since very ancient times. The Jewish historian, Josephus (ca. 37–100), describes the region as inhabited by the Madianite nation as early as 1340 BC, and that the nation was governed by five kings, whom he names: "Rekem; the city which bears his name ranks highest in the land of the Arabs and to this day is called by the whole Arabian nation, after the name of its royal founder, Rekeme: called Petra by the Greeks."[13] The famed architecture of Petra, and other Nabataean sites, was built during indigenous rule in early antiquity, often involving Greek architects.[14][15][16][17]

The Nabataeans were one among several nomadic Bedouin tribes that roamed the Arabian Desert and moved with their herds to wherever they could find pasture and water.[18] They became familiar with their area as seasons passed, and they struggled to survive during bad years when seasonal rainfall diminished.[18] Although the Nabataeans were initially embedded in Aramaic culture, theories about them having Aramean roots are rejected by modern scholars. Instead, archaeological, religious and linguistic evidence confirm that they are a northern Arabian tribe.[19]

The Semitic name of the city, if not Sela, remains unknown. The passage in Diodorus Siculus (xix. 94–97) which describes the expeditions which Antigonus sent against the Nabataeans in 312 BC is understood to throw some light upon the history of Petra, but the "petra" (rock) referred to as a natural fortress and place of refuge cannot be a proper name and the description implies that the metropolis was not yet in existence,[3] although its place was used by Arabians.[20]

The name "Rekem" was inscribed in the rock wall of the Wadi Musa opposite the entrance to the Siq.[21] However, Jordan built a bridge over the wadi and this inscription was buried beneath tons of concrete.[22]

Mid-Antiquity

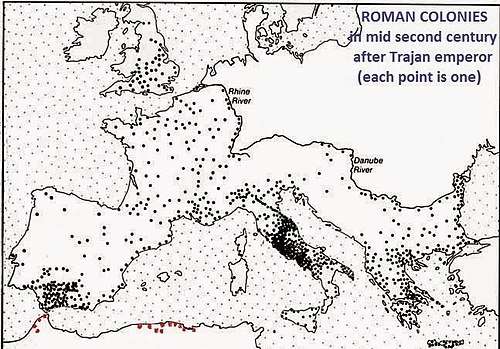

In AD 106, when Cornelius Palma was governor of Syria, the part of Arabia under the rule of Petra was absorbed into the Roman Empire as part of Arabia Petraea and became its capital. The native dynasty came to an end but the city continued to flourish under Roman rule. It was around this time that the Petra Roman Road was built. A century later, in the time of Alexander Severus, when the city was at the height of its splendor, the issue of coinage comes to an end. There is no more building of sumptuous tombs, owing apparently to some sudden catastrophe, such as an invasion by the neo-Persian power under the Sassanid Empire. Meanwhile, as Palmyra (fl. 130–270) grew in importance and attracted the Arabian trade away from Petra, the latter declined. It appears, however, to have lingered on as a religious centre. Another Roman road was constructed at the site. Epiphanius of Salamis (c.315–403) writes that in his time a feast was held there on December 25 in honor of the virgin Khaabou (Chaabou) and her offspring Dushara.[3] Dushara and al-Uzza were two of the main deities of the city, which otherwise included many idols from other Nabatean deities such as Allat and Manat.[23]

Late Antiquity to Early Middle Ages

Petra declined rapidly under Roman rule, in large part from the revision of sea-based trade routes. In 363 an earthquake destroyed many buildings, and crippled the vital water management system.[24] The last inhabitants abandoned the city (further weakened by another major earthquake in 551) when the Arabs conquered the region in 633. The old city of Petra was the capital of the Byzantine province of Palaestina III and many churches were excavated in and around Petra from the Byzantine era. In one of them more than 150 papyri were discovered which contained mainly contracts. The ruins of Petra were an object of curiosity during the Middle Ages and were visited by Sultan Baibars of Egypt towards the end of the 13th century.[3]

19th century

The first European to describe them was Swiss traveller Johann Ludwig Burckhardt during his travels in 1812.[3][25] At that time, the Greek Church of Jerusalem operated a diocese in Al Karak named Battra (باطره in Arabic, and Πέτρας in Greek) and it was the opinion among the clergy of Jerusalem that Kerak was the ancient city of Petra.[25]

The Scottish painter David Roberts visited Petra in 1839 and returned to England with sketches and stories of the encounter with local tribes.

Because the structures weakened with age, many of the tombs became vulnerable to thieves, and many treasures were stolen. In 1929, a four-person team, consisting of British archaeologists Agnes Conway and George Horsfield, Palestinian physician and folklore expert Dr Tawfiq Canaan and Dr Ditlef Nielsen, a Danish scholar, excavated and surveyed Petra.[26]

Numerous scrolls in Greek and dating to the Byzantine period were discovered in an excavated church near the Winged Lion Temple in Petra in December 1993.[27]

T. E. Lawrence

In October 1917, as part of a general effort to divert Ottoman military resources away from the British advance before the Third Battle of Gaza, a revolt of Arabs in Petra was led by British Army officer T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) against the Ottoman regime. The Bedouin women living in the vicinity of Petra and under the leadership of Sheik Khallil's wife were gathered to fight in the revolt of the city. The rebellions, with the support of British military, were able to devastate the Ottoman forces.[28]

Late 20th century: World Heritage Site designation

The Bidoul/Bidul or Petra Bedouin were forcibly resettled from their cave dwellings in Petra to Umm Sayhoun/ Um Seihun by the Jordanian government in 1985, prior to the UNESCO designation process. Here, they were provided with block-built housing with some infrastructure including in particular a sewage and drainage system. Among the six communities in the Petra Region, Umm Sayhoun is one of the smaller communities. The village of Wadi Musa is the largest in the area, inhabited largely by the Layathnah Bedouin, and is now the closest settlement to the visitor centre, the main entrance via the Siq and the archaeological site generally. Umm Sayhoun gives access to the 'back route' into the site, the Wadi Turkmaniyeh pedestrian route.[29]

On December 6, 1985, Petra was designated a World Heritage Site. In a popular poll in 2007, it was also named one of the New7Wonders of the World.

The Bidouls belong to one of the Bedu tribes whose cultural heritage and traditional skills were proclaimed by UNESCO on the Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2005 and inscribed[30] in 2008.

In 2011, following an 11-month project planning phase, the Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority in Association with DesignWorkshop and JCP s.r.l published a Strategic Master Plan that guides planned development of the Petra Region. This is intended to guide planned development of the Petra Region in an efficient, balanced and sustainable way over the next 20 years for the benefit of the local population and of Jordan in general. As part of this, a Strategic Plan was developed for Umm Sayhoun and surrounding areas.[31]

The process of developing the Strategic Plan considered the area's needs from five points of view:

- a socio-economic perspective

- the perspective of Petra Archaeological Park

- the perspective of Petra’s tourism product

- a land use perspective

- an environmental perspective

Petra today

27 sites in Petra are now available on Google Street View.[32]

In 2016, archaeologists discovered a large, previously unknown monumental structure buried beneath the sands of Petra using satellite imagery.[33][34][35]

Issues

The site suffers from a host of threats, including collapse of ancient structures, erosion from flooding and improper rainwater drainage, weathering from salt upwelling,[36] improper restoration of ancient structures and unsustainable tourism.[37] The last has increased substantially, especially since the site received widespread media coverage in 2007 during the New Seven Wonders of the World Internet and cellphone campaign.[38]

In an attempt to reduce the impact of these threats, the Petra National Trust (PNT) was established in 1989. It has worked with numerous local and international organizations on projects that promote the protection, conservation, and preservation of the Petra site.[39] Moreover, UNESCO and ICOMOS recently collaborated to publish their first book on human and natural threats to the sensitive World Heritage sites. They chose Petra as its first and the most important example of threatened landscapes. A book released in 2012, Tourism and Archaeological Heritage Management at Petra: Driver to Development or Destruction?, was the first in a series of important books to address the very nature of these deteriorating buildings, cities, sites, and regions.[40] The next books in the series of deteriorating UNESCO World Heritage Sites will include Machu Picchu, Angkor Wat, and Pompeii.

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) released a video in 2018 highlighting abuse against working animals in Petra. PETA claimed that animals are forced to carry tourists or pull carriages every day. The video showed handlers beating and whipping working animals, with beatings intensifying when animals faltered. PETA also revealed some wounded animals, including camels with fly infested, open wounds.[41] The Jordanian authority running the site responded by opening up a veterinarian clinic, and by spreading awareness among animal handlers.[42]

Religion

The Nabataeans worshipped Arab gods and goddesses during the pre-Islamic era as well as a few of their deified kings. One, Obodas I, was deified after his death. Dushara was the primary male god accompanied by his three female deities: Al-‘Uzzá, Allat and Manāt. Many statues carved in the rock depict these gods and goddesses. New evidence indicates that broader Edomite, and Nabataean theology had strong links to Earth-Sun relationships, often manifested in the orientation of prominent Petra structures to equinox and solstice sunrises and sunsets.[43]

A stele dedicated to Qos-Allah 'Qos is Allah' or 'Qos the god', by Qosmilk (melech – king) is found at Petra (Glueck 516). Qos is identifiable with Kaush (Qaush) the God of the older Edomites. The stele is horned and the seal from the Edomite Tawilan near Petra identified with Kaush displays a star and crescent (Browning 28), both consistent with a moon deity. It is conceivable that the latter could have resulted from trade with Harran (Bartlett 194). There is continuing debate about the nature of Qos (qaus – bow) who has been identified both with a hunting bow (hunting god) and a rainbow (weather god) although the crescent above the stele is also a bow.

Nabatean inscriptions in Sinai and other places display widespread references to names including Allah, El and Allat (god and goddess), with regional references to al-Uzza, Baal and Manutu (Manat) (Negev 11). Allat is also found in Sinai in South Arabian language. Allah occurs particularly as Garm-'allahi – god dedided (Greek Garamelos) and Aush-allahi – 'gods covenant' (Greek Ausallos). We find both Shalm-lahi 'Allah is peace' and Shalm-allat, 'the peace of the goddess'. We also find Amat-allahi 'she-servant of god' and Halaf-llahi 'the successor of Allah'.[44]

The Monastery, Petra's largest monument, dates from the 1st century BC. It was dedicated to Obodas I and is believed to be the symposium of Obodas the god. This information is inscribed on the ruins of the Monastery (the name is the translation of the Arabic "Ad Deir").

Christianity found its way to Petra in the 4th century AD, nearly 500 years after the establishment of Petra as a trade center. Athanasius mentions a bishop of Petra (Anhioch. 10) named Asterius. At least one of the tombs (the "tomb with the urn"?) was used as a church. An inscription in red paint records its consecration "in the time of the most holy bishop Jason" (447). After the Islamic conquest of 629–632 Christianity in Petra, as of most of Arabia, gave way to Islam. During the First Crusade Petra was occupied by Baldwin I of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and formed the second fief of the barony of Al Karak (in the lordship of Oultrejordain) with the title Château de la Valée de Moyse or Sela. It remained in the hands of the Franks until 1189.[3] It is still a titular see of the Catholic Church.[45]

Two Crusader-period castles are known in and around Petra. The first is al-Wu'ayra and is situated just north of Wadi Musa. It can be viewed from the road to "Little Petra". It is the castle of Valle Moise which was seized by a band of Turks with the help of local Muslims and only recovered by the Crusaders after they began to destroy the olive trees of Wadi Musa. The potential loss of livelihood led the locals to negotiate surrender. The second is on the summit of el-Habis in the heart of Petra and can be accessed from the West side of the Qasr al-Bint.

According to Arab tradition, Petra is the spot where Moses (Musa) struck a rock with his staff and water came forth, and where Moses' brother, Aaron (Harun), is buried, at Mount Hor, known today as Jabal Haroun or Mount Aaron. The Wadi Musa or "Wadi of Moses" is the Arab name for the narrow valley at the head of which Petra is sited. A mountaintop shrine of Moses' sister Miriam was still shown to pilgrims at the time of Jerome in the 4th century, but its location has not been identified since.[46]

In popular culture

Literature

- Petra is the main topic in John William Burgon's sonnet "Petra" which won the Newdigate Prize in 1845. The poem refers to Petra as the inaccessible city which he had heard described but had never seen:

It seems no work of Man's creative hand,

- by labour wrought as wavering fancy planned;

But from the rock as if by magic grown,

- eternal, silent, beautiful, alone!

Not virgin-white like that old Doric shrine,

- where erst Athena held her rites divine;

Not saintly-grey, like many a minster fane,

- that crowns the hill and consecrates the plain;

But rose-red as if the blush of dawn,

- that first beheld them were not yet withdrawn;

The hues of youth upon a brow of woe,

- which Man deemed old two thousand years ago,

Match me such marvel save in Eastern clime,

- a rose-red city half as old as time.

- Herman Melville compares Wall Street on a Sunday morning to the abandoned city of Petra in his 1853 short story "Bartleby, the Scrivener."

- Petra appeared in the novels Left Behind Series, Appointment with Death, The Eagle in the Sand, The Red Sea Sharks, the nineteenth book in The Adventures of Tintin series and in Kingsbury's The Moon Goddess and the Son. It played a prominent role in the Marcus Didius Falco mystery novel Last Act in Palmyra. In Blue Balliett's novel, Chasing Vermeer, the character Petra Andalee is named after the site.[47]

- In 1979 Marguerite van Geldermalsen from New Zealand married Mohammed Abdullah, a Bedouin in Petra.[48] They lived in a cave in Petra until the death of her husband. She authored the book Married to a Bedouin. Van Geldermalsen is the only western woman who has ever lived in a Petra cave.

- An Englishwoman, Joan Ward, wrote Living With Arabs: Nine Years with the Petra Bedouin[49] documenting her experiences while living in Umm Sayhoun with the Petra Bedouin, covering the period 2004-2013.

Plays

- Playwright John Yarbrough's tragicomedy, Petra,[50] debuted at the Manhattan Repertory Theatre in 2014[51] and was followed by award-winning performances at the Hudson Guild in New York in 2015.[52] It was selected for the Best American Short Plays 2014-2015 anthology.[53]

Films

- The site appeared in films such as: Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Arabian Nights, Passion in the Desert, Mortal Kombat: Annihilation, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger, The Mummy Returns, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Samsara and Kajraare.

TV

- Petra appeared in episode 3 of the 2010 series An Idiot Abroad.

- Petra appeared in episode 20 of Misaeng.[54][55]

- Petra appeared in an episode of Time Scanners, made for National Geographic, where six ancient structures were laser scanned, with the results built into 3D models.[56] Examining the model of Petra revealed insights into how the structure was built.[57]

- Petra was the focus of an American PBS Nova special, "Petra: Lost City of Stone",[58] which premiered in the US and Europe in February 2015.

Music and music videos

- The power metal band Helloween referred to Petra on their 2013 track "Nabataea" off their album, Straight Out of Hell.

- In 1977, the Lebanese Rahbani brothers wrote the musical "Petra" as a response to the Lebanese Civil War.[59]

- The Sisters of Mercy filmed their music video for "Dominion/Mother Russia" in and around Al Khazneh ("The Treasury") in February 1988.[60]

- In 1994 Petra appeared in the video to the Urban Species video Spiritual Love.[61][62]

- An Austrian symphonic metal band Serenity referred to Petra on their fourth studio album War of Ages (Serenity album) in the track "Shining Oasis"

Video games

- Petra was recreated for the video games Spy Hunter (2001), Outrun 2, King's Quest V, Lego Indiana Jones, Sonic Unleashed, Knights of the Temple: Infernal Crusade, Civilization V, Civilization VI, Europa Universalis IV, Metal Gear Solid 5: The Phantom Pain, and Overwatch.

Gallery

The Siiq, path to Petra

The Siiq, path to Petra The end of the Siq, with its dramatic view of Al Khazneh ("The Treasury")

The end of the Siq, with its dramatic view of Al Khazneh ("The Treasury") Petra is known as the Rose-Red City[63] for the colour of the rocks from which Petra is carved

Petra is known as the Rose-Red City[63] for the colour of the rocks from which Petra is carved Ad Deir ("The Monastery") in 1839, by David Roberts

Ad Deir ("The Monastery") in 1839, by David Roberts- The Petra Visitors Centre in Wadi Musa, the closest town to the historic site

Byzantine mosaic in the Byzantine Church of Petra

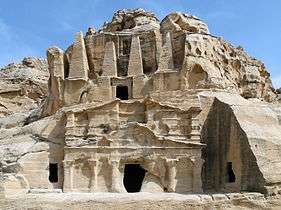

Byzantine mosaic in the Byzantine Church of Petra Obelisk Tomb and the Triclinium

Obelisk Tomb and the Triclinium The Silk Tomb

The Silk Tomb Juniperus phoenicea in Petra

Juniperus phoenicea in Petra- Lonely cave

Sandstone rocks in Siq

Sandstone rocks in Siq Main entrance (Al Khazneh)

Main entrance (Al Khazneh) Theatre

Theatre Tomb of a Roman soldier

Tomb of a Roman soldier- One of the many tombs in Petra

Tomb in Little Petra

Tomb in Little Petra

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Management of Petra". Petra National Trust. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ Browning, Iain (1973, 1982), Petra, Chatto & Windus, London, p. 15, ISBN 0-7011-2622-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

- ↑ Seeger, Josh; Gus W. van Beek (1996). Retrieving the Past: Essays on Archaeological Research and Methodolog. Eisenbrauns. p. 56. ISBN 978-1575060125.

- ↑ "Petra Lost and Found". National Geographic. 2 January 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ↑ ART REVIEW; Rose-Red City Carved From the Rock

- ↑ Major Attractions: Petra, Jordan tourism board

- ↑ "UNESCO advisory body evaluation" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ "Petra: Water Works". Nabataea.net. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ Lisa Pinsker (2001-09-11). "Geotimes – June 2004 – Petra: An Eroding Ancient City". Agiweb.org. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ "Robert Fulford's column about Petra, Jordan". Robertfulford.com. 1997-06-18. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- ↑ "A Short History". Petra National Foundation. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ↑ Josephus, Flavius. "Jewish Antiquities (iv.vii.§1) Translated by H. St. J. Thackeray". Harvard University Press, 1930. doi:10.4159/DLCL.josephus-jewish_antiquities.1930. Retrieved 6 August 2016. – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required)

- ↑ Egger, Vernon O. (2016). A History of the Muslim World to 1405: The Making of a Civilization. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 9781315507682. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ McKenzie, Judith (2007). The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, C. 300 B.C. to A.D. 700, Volume 63. Yale University Press. p. 97. ISBN 0300115555. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Egger, Vernon O. (2017). A History of the Muslim World to 1750: The Making of a Civilization. Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 9781351389075. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Stewart, Andrew (2014). Art in the Hellenistic World: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9781107048577. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- 1 2 Jane, Taylor (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. London, United Kingdom: I.B.Tauris. pp. 14, 17, 30, 31. ISBN 9781860645082. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ Maalouf, Tony (2003). Arabs in the Shadow of Israel: The Unfolding of God's Prophetic Plan for Ishmael's Line. Kregel Academic. ISBN 9780825493638. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus' account of Antigonus' expedition to Arabia, xix, section 95 (note 79).

- ↑ Iain Browning, Petra, Chatto & Windus, 1974. p. 109.

- ↑ "History of Petra". Terhaal Adventures. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- ↑ The Religious Life of Nabataea, Chapter Two, 2013, Peter Alpass

- ↑ Glueck, Grace (2003-10-17). "ART REVIEW; Rose-Red City Carved From the Rock". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- 1 2 John Lewis Burckhardt (1822). Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. J. Murray.

- ↑ Conway, A. and Horsfield, G. 1930. Historical and Topographical Notes on Edom: with an account of the first excavations at Petra. The Geographical Journal, 76 (5), 369–390.

- ↑ Petra-National Geographic

- ↑ Thomas, Lowell, With Lawrence in Arabia, The Century Co., 1924, pps. 180–187

- ↑ "Map of the area from the go2petra website".

- ↑ "The Cultural Space of the Bedu in Petra and Wadi Rum". UNESCO Culture Sector. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ↑ Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority in Association with DesignWorkshop and JCP s.r.l: Strategic Plan for Umm Sayhoun and surrounding areas Accessed 8 April 2017

- ↑ Google Street View – Explore natural wonders and world landmarks

- ↑ Parcak, Sarah; Tuttle, Christopher A. (May 2016). "Hiding in Plain Sight: The Discovery of a New Monumental Structure at Petra, Jordan, Using WorldView-1 and WorldView-2 Satellite Imagery". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (375): 35–51. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.375.0035. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.375.0035.

- ↑ "Archaeologists discover massive Petra monument that could be 2,150 years old". The Guardian. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Massive New Monument Found in Petra". National Geographic. 8 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Heinrichs, K., Azzam, R.: "Investigation of salt weathering on stone monuments by use of a modern wireless sensor network exemplified for the rock-cut monuments in Petra / Jordan – a research project International Journal of Heritage in the Digital Era, Volume 1, Nr. 2 / Juni 2012, S. 191–216

- ↑ Heritage at Risk 2004/2005: Petra, at icomos.org Accessed 27 March 2017

- ↑ "Heritage Conservation Grips Jordan's Petra Amid Booming Tourism". Xinhua. November 3, 2007. Archived from the original on September 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Petra National Trust-About". Petranationaltrust.org. Archived from the original on 2011-12-28. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ Comer and Willems. "Tourism and Archaeological Heritage Management at Petra: Driver to Development or Destruction?" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- ↑ Usher, Sebastian (January 16, 2018). "Jordan urged to end animal mistreatment at Petra site". BBC News. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Stakeholders take steps to address animal abuse in Petra". Saeb Rawashdeh. The Jordan Times. 5 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ↑ Paradise T.R. & Angel C.C. 2015, Nabatean Architecture and the Sun, ArcUser (Winter).

- ↑ Negev 11

- ↑

- ↑ "Petra". Sacred Sites. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ Balliett, Blue (2004). Chasing Vermeer: Afterwords by Leslie Budnick: Author Q&A. Scholastic. ISBN 0-439-37294-1.

- ↑ Geldermalsen, Marguerite (2010). Married to a Bedouin. Virago UK. ISBN 978-1844082209.

- ↑ Ward, Joan (2014). Living With Arabs: Nine Years with the Petra Bedouin. UM Peter Publishing. ISBN 978-1502564917.

- ↑ "John Yarbrough's Petra on Youtube".

- ↑ "Manhattan Repertory Theatre fall one act competition 2014 including John Yarbrough's Petra". Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ↑ "Broadwayworld, Off-Off-Broadway, article: 'Playwright John Yarbrough Wins Strawberry One Act Festival'". Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ↑ "Broadwayworld, Off-Off-Broadway, article: 'The Best American Short Plays 2014-15 Hits the Shelves'".

- ↑ "Scenes for TV drama series 'Misaeng' shot around Kingdom.The Jordan Times". The Jordan Times.

- ↑ "Misaeng Episode 20 Final". dramabeans.com.

- ↑ Time Scanners Archived 2015-09-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Time Scanners: How was Petra built?

- ↑ Petra-Lost City in building-wonders at pbs.org

- ↑ Stone, Christopher. Popular Culture and Nationalism in Lebanon.

- ↑ imdb.com page for The Sisters of Mercy

- ↑ Urban Species Spiritual Love music video at nme.com

- ↑ Urban Species Spiritual Love music video (similar to video formerly at nme.com) at jukebo.com Accessed 30 March 2017

- ↑ "The Rose-Red City of Petra". Grisel.net. 2001-04-26. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

Bibliography

- Bedal, Leigh-Ann (2004). The Petra Pool-Complex: A Hellenistic Paradeisos in the Nabataean Capital. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-120-7.

- Brown University. "The Petra Great Temple; History" Accessed April 19, 2013.

- Glueck, Nelson (1959). Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev. New York: Farrar, Straus & Cudahy/London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Harty, Rosemary. "The Bedouin Tribes of Petra Photographs: 1986–2003". Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Hill, John E. (2004). The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢 : A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE.

Draft annotated English translation where Petra is referred to as the Kingdom of Sifu.

- Mouton, Michael and Schmid, Stephen G. (2013) "Men on the Rocks: The Formation of Nabataean Petra"

- Paradise, T. R. (2011). "Architecture and Deterioration in Petra: Issues, trends and warnings" in Archaeological Heritage at Petra: Drive to Development or Destruction?" (Doug Comer, editor), ICOMOS-ICAHM Publications through Springer-Verlag NYC: 87–119.

- Paradise, T. R. (2005). "Weathering of sandstone architecture in Petra, Jordan: influences and rates" in GSA Special Paper 390: Stone Decay in the Architectural Environment: 39–49.

- Paradise, T. R. and Angel, C. C. (2015). Nabataean Architecture and the Sun: A landmark discovery using GIS in Petra, Jordan. ArcUser Journal, Winter 2015: 16-19pp.

- Reid, Sara Karz (2006). The Small Temple. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-339-0.

Reid explores the nature of the small temple at Petra and concludes it is from the Roman era.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Petra" Accessed April 19, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Petra, Jordan. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Petra. |

- Petra Archaeological Park

- Video overview of Petra

- Petra In The Early 1800s

- 3D-tour on Petra (Russian)

- University of Arkansas Petra Project, Accessed 27 March 2017

- Smart e Guide, interactive map of Petra

- Open Context, "Petra Great Temple Excavations (Archaeological Data)", Open Context Publication of Archaeological Data from the 1993–2006 Brown University Excavations at the Great Temple of Petra, Jordan

- Petra iconicarchive, photo gallery

- Petra History and Photo Gallery, Accessed 27 March 2017 History with Maps

- Parker, S., R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies, S. Gillies, J. Becker. "Places: 697725 (Petra)". Pleiades. <http://pleiades.stoa.org/places/697725> [Accessed: March 7, 2012 4:18 pm]

- Pictures on Petra

- Almost 800 pictures with captions, some panoramas

- Jordanian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

- Why was Petra abandoned by its inhabitants? | Check123 Video Encyclopedia