Emmaus Nicopolis

|

The Byzantine Basilica of Emmaus Nicopolis (5th-7th centuries C.E.), restored by Crusaders during the 12th century | |

Location of Emmaus Nikopolis | |

| Location | Canada Park |

|---|---|

| Region | West Bank |

| Coordinates | 31°50′22″N 34°59′22″E / 31.83944°N 34.98944°ECoordinates: 31°50′22″N 34°59′22″E / 31.83944°N 34.98944°E |

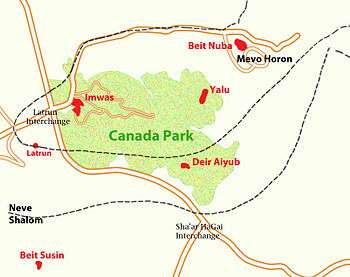

Emmaus Nicopolis (lit. "Emmaus City of Victory") was the Roman name for one of the towns associated with the Emmaus of the New Testament, where Jesus is said to have appeared after his death and resurrection. Emmaus was the seat of the Roman Emmaus Nicopolis was the name of the city from the 3rd century CE until the conquest of Palestine by the Muslim forces of the Rashidun Caliphate in 639. In the modern age, the site was the location of the Palestinian Arab village of Imwas, near the Latrun junction, between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, before its destruction in 1967. The site today is inside Canada Park, a place maintained by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, although the archaeological site has been cared for by a resident French Catholic community since 1993.[1][2]

Location

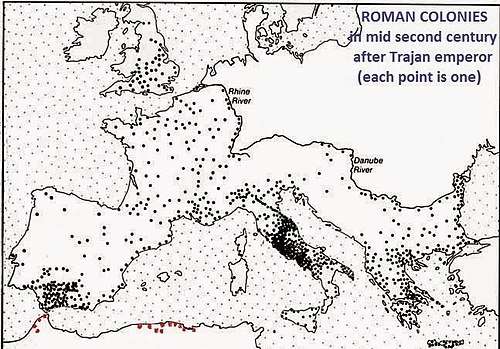

Emmaus Nicopolis appears on Roman geographical maps. The Peutinger Table situates it about 31 kilometres (19 mi) west of Jerusalem, while the Ptolemy map shows it at a distance of 32 kilometres (20 mi) from the city. The Emmaus in the Gospel of Luke seems to lie some 12.1 kilometres (7.5 mi) from Jerusalem, though a textual minor variant, conserved in Codex Sinaiticus, gives the distance between the New Testament Emmaus and Jerusalem as 160 stadia.[3] The geographical position of Emmaus is described in the Jerusalem Talmud, Tractate Sheviit 9.2:[4]

From Bet Horon to the Sea is one domain. Yet is it one domain without regions? Rabbi Johanan said, ‘Still there is Mountain, Lowland, and Valley. From Bet Horon to Emmaus (Hebrew: אמאום, lit. 'Emmaum') it is Mountain, from Emmaus to Lydda Lowland, from Lydda to the Sea Valley. Then there should be four stated? They are adjacent’.

Etymology

The name for Emmaus was hellenized during the 2nd century BCE and appears in Jewish and Greek texts in many variations: Ammaus, Ammaum, Emmaus, Emmaum, Maus, Amus, etc.: Greek: Άμμαούμ, Άμμαούς, Έμμαούμ, Έμμαούς, Hebrew: אמאוס, אמאום, עמאוס, עמאום, עמוס, מאום, אמהום[2]

Emmaus may derive from the Hebrew ḥammaṭ (Hebrew: חמת) meaning "hot spring",[5] and is generally referred to in Hebrew sources as Ḥamtah or Ḥamtān.[6] A spring of Emmaus (Greek: Ἐμμαοῦς πηγή), or alternatively a 'spring of salvation' (Greek: πηγή σωτήριος) is attested in Greek sources.[7] Emmaus is mentioned by this name in Midrash Zutta for Song of Songs 6,8 and Midrash Rabba for Lamentations 1,45,[2] and in the Midrash Rabba on Ecclesiastes (7:15).[8]

Religious significance

Emmaus is mentioned in the Gospel of Luke[9] as the village where Jesus appeared to his disciples after his crucifixion and resurrection:

That very day two of them were going to a village (one hundred and) sixty stadia away from Jerusalem called Emmaus, and they were speaking about all the things that had occurred. And it happened that while they were speaking and debating, Jesus himself drew near and walked with them, but their eyes were prevented from recognizing him … As they approached the village to which they were going, he gave the impression that he was going on further. But they urged him, ‘Stay with us, for it is nearly evening and the day is declining.’ So he went in to stay with them. And it happened that, while he was with them at table, he took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them. With that their eyes were opened and they recognized him.

A Christian scholar and writer born in Jerusalem, Julius Africanus, who said he had interviewed descendants of Jesus' relatives, put Emmaus once more on the map. He headed an embassy to Rome and had an interview with the Roman emperor Elagabalus on behalf of Emmaus, then a small Palestinian village (κώμη).

History

Classic era

Emmaus

Due to its strategic position, Emmaus played an important administrative, military and economic role in history. The first mention of Emmaus occurs in the 1st book of Maccabees, chapters 3-4, in the context of Judas the Maccabee’s wars against the Greeks (2nd century BCE). The first battles of the Hasmoneans are traditionally believed occurred in this area.[8]

During the Hasmonean period, Emmaus became a regional administrative centre (toparchy) in the Ayalon Valley.[10] Josephus Flavius mentions Emmaus in his writings several times.[11] He speaks about the destruction of Emmaus by the Romans in the year 4 BCE.[12] The importance of the city was recognized by the Emperor Vespasian, who established a fortified camp there in 68 CE to house the fifth ("Macedonian") legion,[13] populating it with 800 veterans,[14][15] though this may refer to Qalunya rather than Emmaus Nicopolis.[16] Archaeological works indicates that the town was cosmopolitan, with a mixed Jewish, pagan and Samaritan population, the presence of the last group being attested by the remains of a Samaritan synagogue.[6]

In 130 or 131 CE, the city was destroyed by an earthquake. In 132, the ruins of Emmaus fortress were briefly reconstructed by Judean rebels under Simon Bar Kokhba and used as a hideout during the revolt.[17]

Nikopolis

The city of Nikopolis was founded on the ruins of Emmaus in early 3rd century CE. Soon after it was refounded to become a "city" (πόλις), which quickly became famous, and was given the qualification of 'Nicopolis'.[18]

St. Eusebius writes "Emmaus, whence was Cleopas who is mentioned by the Evangelist Luke. Today it is Nicopolis, a famous city of Palestine."[19]

In 222 CE, a basilica was erected there, which was rebuilt first by the Byzantines and later modified by the Crusaders.[6]

During the Byzantine period Emmaus-Nicopolis became a large city and a bishopric. A substantial church complex was erected on the spot where tradition maintained the apparition of the risen Christ had occurred, a site which then became a place of pilgrimage, and whose ruins are still extant.

Middle Ages

At the time of the Muslim conquest of Palestine, the main encampment of the Arab army was established in Emmaus, when a plague (ța'ūn) struck, carrying off many of Companions of the Prophet. This first encounter of the Arab armies with the chronic plagues of Syria was later referred to as the 'plague of 'Amawās', a and the event marked the decline of Emmaus Nicopolis. A well on the site still bears an inscription reading "the well of the plague" (bi'r aț-ța'ūn).[6]

During the Crusader period, the Christian presence resumed at Emmaus, and the Byzantine church was restored. However, the memory of the apparition of the risen Jesus at Emmaus also started to be celebrated in three other places in the Holy Land: Motza (c. 6 kilometres (4 mi) west of Jerusalem), Qubeibe (c. 11 kilometres (7 mi) northwest of Jerusalem) Abu Ghosh (c. 11 kilometres (7 mi) west of Jerusalem).

Ottoman era

The Arab village of Amwas was identified once again as the biblical Emmaus and the Roman-Byzantine Nicopolis by scholars in the 19th century, including Edward Robinson(1838–1852),[20][21] M.-V. Guérin (1868), Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau (1874), and J.-B. Guillemot (1880–1887). In addition, a local saint named Blessed Mariam of Jesus Crucified, a nun of the Carmelite monastery of Bethlehem, had a revelation in 1878 in which Jesus appeared to indicate Amwas was the Gospel Emmaus. On the basis of this revelation, the holy place of Emmaus was acquired by the Carmelite order from the Muslims in 1878, excavations were carried out, and the flow of pilgrims to Emmaus-Nicopolis resumed.

British rule

In 1930, the Carmelite Order built a monastery, the House of Peace, on the tract of land purchased in 1878. In November 1947, the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine attributed the area to the Arab State.

Jordanian rule

Israelis and Jordanians fought during the battle of Latrun for the control of this strategic zone which blockaded the road to Jerusalem. As part of the outcome of the war the Palestinian village of Imwas, which lay on the site of Emmaus Nicopolis, fell within the West Bank territory under Jordanian rule.

Israeli rule

In 1967, after the Six-Day War the residents of Imwas Israeli forces expelled the population and the village was razed by bulldozers,[22] leaving the Byzantine-crusader church, called in Arabic, al-Kenisah,[23] intact in their cemetery. The Catholic congregation, the Community of the Beatitudes, renovated the site in 1967–1970 and opened the French Center for the Study of the Prehistory of the Land of Israel next to it where they were allowed to settle in 1993.[24]

Subsequently, Canada Park was created in 1973, financed by the Jewish National Fund (JNF) of Canada, and included the plantation of a forest on the rubble of Imwas/Emmaus[25] The site became a favourite picnic ground for Israelis[26] and the Latrun salient an area of Israeli commemoration of its War of Independence.[27][28]

Archaeology

Archaeological excavations in Imwas started in the late 19th century and continue nowadays: Clermont-Ganneau (1874), J.-B. Guillemot (1883–1887), Dominican Fathers L.-H. Vincent & F.-M. Abel (1924–1930),[29] Y. Hirschfeld (1975),[30] M. Gichon (1978),[31] Mikko Louhivuori, M. Piccirillo, V. Michel, K.-H. Fleckenstein (since 1994).[32] During excavations in Canada Park ( Ayalon forest) ruins of Emmaus fortifications from the Hasmonean era were discovered, along with a Roman bathhouse from the 3rd century CE, Jewish burial caves from the 1st century CE, Roman-Byzantine hydraulic installations, oil presses and tombs. Other findings were coins, oil lamps, vessels, jewellery. The eastern (rear) three-apsidal wall of the Byzantine church was cleared, with an external baptistery and polychrome mosaics, as well as walls of the Crusader church which were built against the central Byzantine apse (12th century). In the area of Emmaus, several Hebrew, Samaritan, Greek and Latin inscriptions carved on stones have been found.

Identification with the Gospel site

Most manuscripts of the Gospel of Luke which came down to us indicate the distance of 60 stadia (c. 11 km) between Jerusalem and Emmaus. However, there are several manuscripts which state the distance as 160 stadia (31 km). These include the uncial manuscripts א (Codex Sinaiticus), Θ, Ν, Κ, Π, 079 and cursive (minuscule) manuscripts 158, 175, 223, 237, 420, as well as ancient lectionnaries[33] and translations into Latin (some manuscripts of the Vetus Latina,[34] high-quality manuscripts of the Vulgate[35]), in Aramaic,[36] Georgian and Armenian languages.[37] The version of 60 stadia has been adopted for the printed editions of the Gospel of Luke since the 16th century. The main argument against the version of 160 stadia claims that it is impossible to walk such a distance in one day. In keeping with the principle of Lectio difficilior, lectio verior, the most difficult version is presumed to be genuine, since ancient copyists of the Bible were inclined to change the text in order to facilitate understanding, but not vice versa. One should also note that it is possible to walk from Jerusalem to Emmaus-Nicopolis and back in one day.

The ancient Jewish sources (1 Maccabees, Josephus Flavius, Talmud and Midrash) mention only one village called Emmaus in the area of Jerusalem: Emmaus of Ajalon Valley.[38] For example, in the "Jewish War" (4, 8, 1) Josephus Flavius mentions that Vespasian placed the 5th Macedonian Legion in Emmaus. This has been confirmed by archaeologists who have discovered inscribed tombstones of the Legion’s soldiers in the area of Emmaus-Nicopolis.[39] (The village of Motza, located 30 stadia (c. 6 kilometres (4 mi)) away from Jerusalem, is mentioned in medieval Greek manuscripts of the "Jewish war" of Josephus Flavius (7,6,6) under the name of Ammaus, apparently as a result of copyists’ mistake).[40][41]

The ancient Christian tradition of the Church fathers, as well as pilgrims to the Holy Land during the Roman-Byzantine period, unanimously recognized Nicopolis as the Emmaus in the Gospel of Luke (Origen (presumably), Eusebius of Caesarea,[42] St. Jerome,[43] Hesychius of Jerusalem,[44] Theophanes the Confessor,[45] Sozomen,[46] Theodosius,[47] etc.).

See also

References

- ↑ Thiede p.55.

- 1 2 3 "Emmaus-Nicopolis". Community of the Beatitudes. 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ↑ Steve Mason, (ed.), Flavius Josephus : translation and Commentary, Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary. Judean war. Vol. 1B, BRILL, 2008 p.44 n.388.

- ↑ H. Guggenheimer, trans., Berlin-N.Y. 2001, p.609

- ↑ 'Emmaus,' in Geoffrey W. Bromiley (ed.), International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J, Wm.B. Eerdmanns Publishers 1995 p.77

- 1 2 3 4 Sharon, 1997, p. 80

- ↑ Esti Dvorjetski, Leisure, Pleasure and Healing: Spa Culture and Medicine in Ancient Eastern Mediterranean, BRILL, 2007 p.221.

- 1 2 "Ayalon Canada Park - Biblical & Modern Israel". Forests, Parks and Sites. Jewish National Fund. 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ↑ Luke 24:13-16, 28-31

- ↑ see Josephus Flavius, "The Jewish War" 3,3,5

- ↑ "The Jewish War" 2, 4, 3; 2, 20, 4; 3, 3, 5; 4, 8, 1; 5, 1, 6; "The Antiquities of the Jews" 14, 11, 2; 14, 15, 7 ; 17, 10, 7-9)

- ↑ "Antiquities of the Jews" 17, 10, 7-9

- ↑ Sharon, 1997, p.79

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Iudaico Bk 7,6:6.

- ↑ Günter Stemberger,'Jews and Graeco-Roman Culture:from Alexander to Theodosius 11,' in James K. Aitken, James Carleton Paget (eds.), The Jewish-Greek Tradition in Antiquity and the Byzantine Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2014 pp.15-36 p.29.

- ↑ Thiede pp.40-41.

- ↑

- ↑ William Adler, 'The Kingdom of Edessa and the Creation of a Christian Aristocracy,' in Natalie B. Dohrmann, Annette Yoshiko Reed (eds.),Jews, Christians, and the Roman Empire: The Poetics of Power in Late Antiquity, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013 pp.43-61 p.58.

- ↑ "Onomasticon," 90:15-17, a text written in 290-325 A.D., G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville, trans., Jerusalem, 2003

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, p. 363

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1856, pp. 146-148

- ↑ Rich Wiles, Behind the Wall: Life, Love, and Struggle in Palestine, Potomac Books, Inc., 2010, pp. 17–24.

- ↑ Dvorjetski p.221.

- ↑ Rami Degani, Ruth Kark,'Christian and Messianic Jews’ Communes in Israel:Past, Present and Future,' in Eliezer Ben-Rafael, Yaacov Oved, Menachem Topel (eds.) The Communal Idea in the 21st Century, BRILL, 2012, pp.221–239 p.236.

- ↑ Max Blumenthal, Goliath: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel, Nation Books, 2014 p.185

- ↑ Adam LeBor, City of Oranges: Arabs and Jews in Jaffa, A&C Black, 2007 p.326.

- ↑ Ben-Yehuda, Nachman (1996). "The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel". University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 159–160.

- ↑ "PYad La'Shyrion". Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ Vincent, Abel "Emmaüs", Paris, 1932

- ↑ Y. Hirschfeld, "A Hidraulic Installation in the Water-Supply System of Emmaus-Nicopolis", IEJ, 1978

- ↑ M. Gichon, "Roman Bath-houses in Eretz Israel", Qadmoniot 11, 1978

- ↑ K.-H. Fleckenstein, M. Louhivuori, R. Riesner, "Emmaus in Judäa", Giessen-Basel, 2003. ISBN 3-7655-9811-9

- ↑ L844, L2211

- ↑ e.g. Codex Sangermanensis

- ↑ including the oldest of them, Codex Fuldensis

- ↑ Palestinian Evangeliary

- ↑ Lagrange, 1921, pp. 617-618; Wieland Willker, "A Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels", Vol. 3 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-03. Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- ↑ Strack, Billerbeck, "Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud & Midrasch", vol II, München, 1924,1989, p.p. 269-271. ISBN 3-406-02725-3

- ↑ See : P. M. Séjourné, "Nouvelles de Jérusalem", RB 1897, p. 131; E. Michon, "Inscription d'Amwas", RB 1898, p. 269-271; J. H. Landau, "Two Inscribed Tombstones", "Atiqot", vol. XI, Jerusalem, 1976.

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1856, p. 149

- ↑ Schlatter, 1896, p. 222; Vincent & Abel, 1932, pp. 284-285

- ↑ "Onomasticon"

- ↑ Letter 108, PL XXII, 833 and other texts

- ↑ Quaestiones », PG XCIII, 1444

- ↑ "Chronografia", PG CVIII, 160

- ↑ "Ecclesiastical History", PG LXVII, 180

- ↑ "De situ Terrae sanctae", 139

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emmaus Nicopolis. |

- Duvignau, P. 1937. Emmaüs, le site - le mystère, Paris,

- Fleckenstein, K.-H., M. Louhivuori, R. Riesner, "Emmaus in Judäa", Giessen-Basel, 2003. ISBN 3-7655-9811-9.

- Lagrange, Marie-Joseph (1921). Evangile selon Saint Luc. Paris: Libraire Victor Lecoffre.

- Michel, V., "Le complexe ecclésiastique d'Emmaüs-Nicopolis", Paris, Sorbonne,1996–1997, pro manuscripto.

- Robinson, Edward; Smith, Eli (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, Edward; Smith, Eli (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray.

- Schlatter, A. (1896). "Einige Ergebnisse aus Niese's Ausgabe des Josephus". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 221–231.

- Segev, Tom (2007). 1967: Israel, the War, and the Year that Transformed the Middle East. Translated by Jessica Cohen. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-7057-6.

- Sharon, Moshe (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, A. 1. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10833-5.

- Vincent, Louis-Hugues; Abel, Félix-Marie (1932). Emmaüs, Sa Basilique Et Son Histoire (in French). 1. Paris.